Banking Crises and Financial Panics

A banking crisis occurs when a large part of the depository banking sector or the shadow banking sector fails or threatens to fail.

Bank failures are common: even in a good year, several U.S. banks typically go under for one reason or another. And shadow banks sometimes fail, too. Banking crises—episodes in which a large part of the depository banking sector or the shadow banking sector fails or threatens to fail—are relatively rare by comparison. Yet they do happen, often with severe negative effects on the broader economy. What would cause so many of these institutions to get into trouble at the same time? Let’s take a look at the logic of banking crises, then review some of the historical experiences.

The Logic of Banking Crises

When many banks—either depository banks or shadow banks—get into trouble at the same time, there are two possible explanations. First, many of them could have made similar mistakes, often due to an asset bubble. Second, there may be financial contagion, in which one institution’s problems spread and create trouble for others.

In an asset bubble, the price of an asset is pushed to an unreasonably high level due to expectations of further price gains.

Shared Mistakes In practice, banking crises usually owe their origins to many banks making the same mistake of investing in an asset bubble. In an asset bubble, the price of some kind of asset, such as housing, is pushed to an unreasonably high level by investors’ expectations of further price gains. For a while, such bubbles can feed on themselves. A good example is the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, when there was a huge boom in the construction of commercial real estate, especially office buildings. Many banks extended large loans to real estate developers, believing that the boom would continue indefinitely. By the late 1980s, it became clear that developers had gotten carried away, building far more office space than the country needed. Unable to rent out their space or forced to slash rents, a number of developers defaulted on their loans—and the result was a wave of bank failures.

A similar phenomenon occurred between 2002 and 2006, when rapidly rising housing prices led many people to borrow heavily to buy a house in the belief that prices would keep rising. This process accelerated as more buyers rushed into the market and pushed housing prices up even faster. Eventually the market runs out of new buyers and the bubble bursts. At this point asset prices fall; in some parts of the United States, housing prices fell by half between 2006 and 2009. This, in turn, undermines confidence in financial institutions that are exposed to losses due to falling asset prices. This loss of confidence, if it’s sufficiently severe, can set in motion the kind of economy-wide vicious downward spiral that marks a financial contagion.

A financial contagion is a vicious downward spiral among depository banks or shadow banks: each bank’s failure worsens fears and increases the likelihood that another bank will fail.

Financial Contagion In especially severe banking crises, a vicious downward spiral of financial contagion occurs among depository banks or shadow banks: each institution’s failure worsens depositors’ or lenders’ fears and increases the odds that another bank will fail.

As already noted, one underlying cause of contagion arises from the logic of bank-runs. In the case of depository banks, when one bank fails, depositors are likely to become nervous about others. Similarly in the case of shadow banks, when one fails, lenders in the short-term credit market become nervous about lending to others. The shadow banking sector, because it is largely unregulated, is especially prone to fear- and rumor-driven contagion.

There is also a second channel of contagion: asset markets and the vicious cycle of deleveraging. When a financial institution is under pressure to reduce debt and raise cash, it tries to sell assets. To sell assets quickly, though, it often has to sell them at a deep discount. The contagion comes from the fact that other financial institutions own similar assets, whose prices decline as a result of the “fire sale.” This decline in asset prices hurts the other financial institutions’ financial positions, too, leading their creditors to stop lending to them. This knock-on effect forces more financial institutions to sell assets, reinforcing the downward spiral of asset prices. This kind of downward spiral was clearly evident in the months immediately following Lehman’s fall: prices of a wide variety of assets held by financial institutions, from corporate bonds to pools of student loans, plunged as everyone tried to sell assets and raise cash. Later, as the severity of the crisis abated, many of these assets saw at least a partial recovery in prices.

A financial panic is a sudden and widespread disruption of the financial markets that occurs when people suddenly lose faith in the liquidity of financial institutions and markets.

Combine an asset bubble with a huge, unregulated shadow banking system and a vicious cycle of deleveraging and it is easy to see, as the U.S. economy did in 2008, how a full-blown financial panic—a sudden and widespread disruption of financial markets that happens when people suddenly lose faith in the liquidity of financial institutions and markets—can arise. A financial panic almost always involves a banking crisis, either in the depository banking sector, or the shadow banking sector, or both.

Because banking provides much of the liquidity needed for trading financial assets like stocks and bonds, severe banking crises almost always lead to disruptions of the stock and bond markets. Disruptions of these markets, along with a headlong rush to sell assets and raise cash, lead to a vicious circle of deleveraging. As the panic unfolds, savers and investors come to believe that the safest place for their money is under their bed, and their hoarding of cash further deepens the distress.

So what can history tell us about banking crises and financial panics?

Historical Banking Crises: The Age of Panics

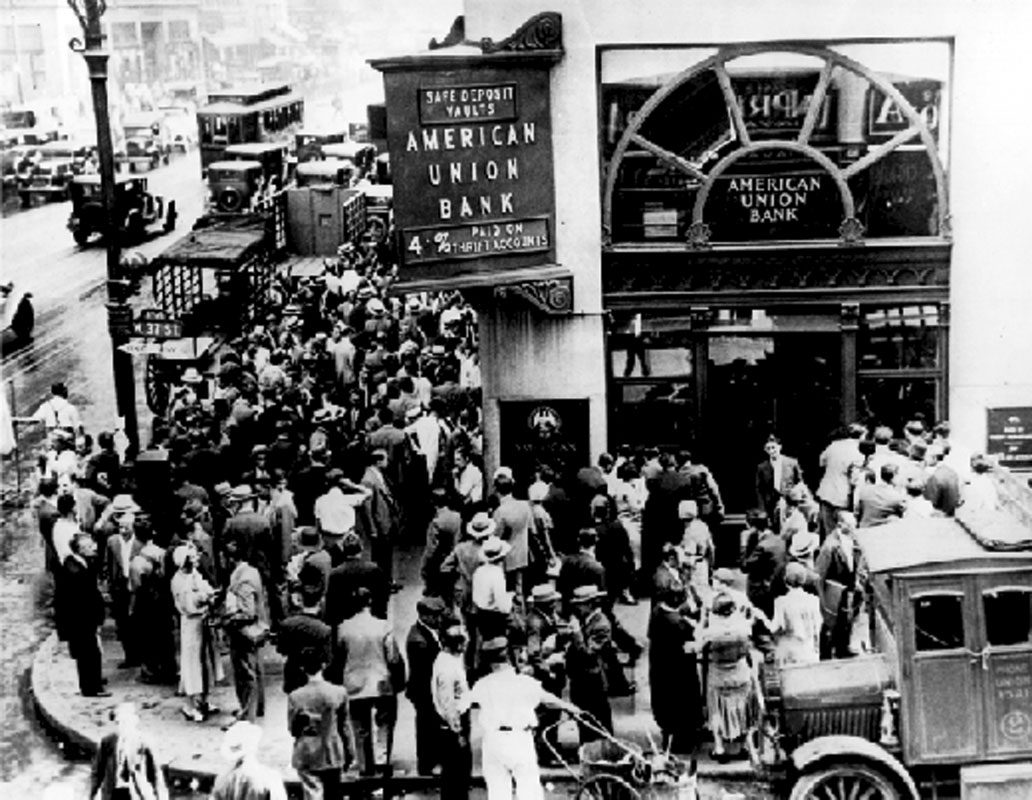

Between the Civil War and the Great Depression, the United States had a famously crisis-prone banking system. Even then, banks were regulated: most banking was carried out by “national banks” that were regulated by the federal government and subject to rules involving reserves and capital, of the kind described below. However, there was no system of guarantees for depositors. As a result, bank-runs were common, and banking crises, also known at the time as panics, were fairly frequent.

Table 18-1 shows the dates of these nationwide banking crises and the number of banks that failed in each episode. Notice that the table is divided into two parts. The first part is devoted to the “national banking era,” which preceded the 1913 creation of the Federal Reserve—which was supposed to put an end to such crises. It failed. The second part of the table is devoted to the epic waves of bank failures that took place in the early 1930s.

TABLE 18-1 Number of Bank Failures: National Banking Era and Great Depression

| National Banking era (1863–1912) | Great Depression (1929–1941) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Panic dates | Number of failures | Panic dates | Number of failures |

| September 1873 | 101 | November–December 1930 | 806 |

| May 1884 | 42 | April–August 1931 | 573 |

| November 1890 | 18 | September–October 1931 | 827 |

| May–August 1893 | 503 | June–July 1932 | 283 |

| October–December 1907 | 73* | February–March 1933 | Bank holiday |

| *This understates the scale of the 1907 crisis because it doesn’t take into account the role of trusts. | |||

The events that sparked each of these panics differed. In the nineteenth century, there was a boom-and-bust cycle in railroad construction somewhat similar to the boom-and-bust cycle in office building construction during the 1980s. Like modern real estate companies, nineteenth-century railroad companies relied heavily on borrowed funds to finance their investment projects. And railroads, like office buildings, took a long time to build. This meant that there were repeated episodes of overbuilding: competing railroads would invest in expansion, only to find that collectively they had laid more track than the demand for rail transport warranted. When the overbuilding became apparent, business failures, debt defaults, and an overall banking crisis followed. The Panic of 1873 began when Jay Cooke and Co., a financial firm with a large stake in the railroad business, failed. The Panic of 1893 began with the failure of the overextended Philadelphia and Reading Railroad.

As we’ll see later in this chapter, the major financial panics of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were followed by severe economic downturns. However, the banking crises of the early 1930s made previous crises seem minor by comparison. In four successive waves of bank-runs from 1930 to 1932, about 40% of the banks in America failed. In the end, Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared a temporary closure of all banks—the so-called “bank holiday”—to put an end to the vicious circle. Meanwhile, the economy plunged, with real GDP shrinking by a third and a sharp fall in prices as well.

There is still considerable controversy about the banking crisis of the early 1930s. In part, this controversy is about cause and effect: did the banking crisis cause the wider economic crisis, or vice versa? (No doubt causation ran in both directions, but the magnitude of these effects remains disputed.) There is also controversy about the extent to which the banking crisis could have been avoided. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, in their famous study Monetary History of the United States, argued that the Federal Reserve could and should have prevented the banking crisis—and that if it had, the Great Depression itself could also have been prevented. However, this view has been disputed by other economists.

In the United States, the experience of the 1930s led to banking reforms that prevented a replay for more than 70 years. Outside the United States, however, there were a number of major banking crises.

Modern Banking Crises Around the World

Around the world, banking crises are relatively frequent events. However, the ways in which they occur differ according to the banking sector’s particular institutional framework. According to a 2008 analysis by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), no fewer than 127 banking crises occurred around the world between 1970 and 2007. Most of these were in small, poor countries that lack the regulatory safeguards found in advanced countries. In poorer countries, banks generally get in trouble in much the same way: insufficient capital, poor accounting, too many loans and, often, corruption. But banks in advanced countries can also make the same mistakes—for example, there was the Savings and Loans (S&L) crisis in the United States during the 1980s (described in Chapter 16).

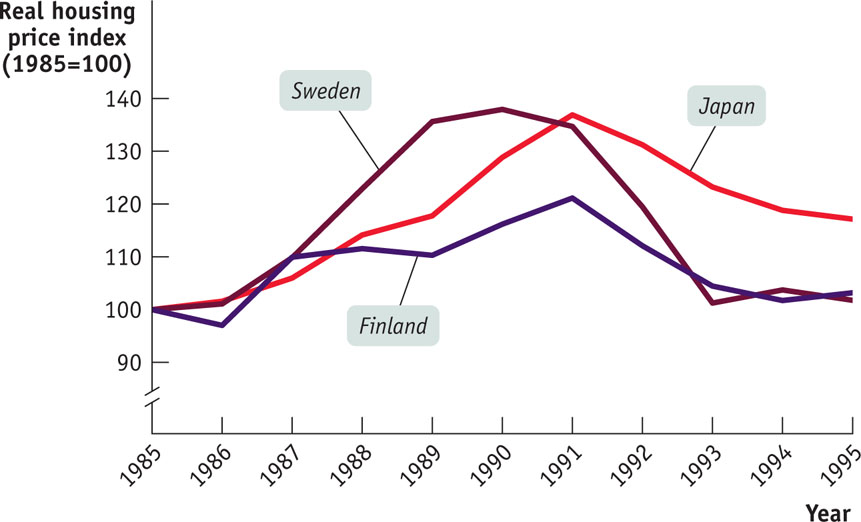

In more advanced countries, banking crises almost always occur as a consequence of an asset bubble—typically in real estate. Between 1985 and 1995, three advanced countries—Finland, Sweden, and Japan—experienced banking crises due to the bursting of a real estate bubble. Banks in the three countries lent heavily into a real estate bubble that their lending helped to inflate. Figure 18-1 shows real estate prices, adjusted for inflation, in Finland, Sweden, and Japan from 1985 to 1995. As you can see, in each country a sharp rise was followed by a drastic fall, leading many borrowers to default on their real estate loans, pushing large parts of each country’s banking system into insolvency.

FIGURE 18-1 Real Housing Prices in Three Banking Crises

In the United States, the fall of Lehman in September 2008 precipitated a banking crisis in the shadow banking sector that included financial contagion as well as financial panic, but left the depository banking sector largely unaffected. As we discussed in the opening story, the financial crisis of 2008 was devastating because of securitization, which had distributed subprime mortgage loans throughout the entire shadow banking sector both in the United States and abroad.

Immediately after the crisis, the size of the shadow banking sector decreased as investors rediscovered the benefits of regulation and the safety of the depository banking sector. However, the shadow banking sector has since recovered, and it is now significantly larger than it was before the crisis. In the next section, we will learn how troubles in the banking sector soon translate into troubles for the broader economy.

Erin Go Broke

For much of the 1990s and 2000s, Ireland was celebrated as an economic success story: the “Celtic Tiger” was growing at a pace the rest of Europe could only envy. But the miracle came to an abrupt halt in 2008, as Ireland found itself facing a huge banking crisis.

Like the earlier banking crises in Finland, Sweden, and Japan, Ireland’s crisis grew out of excessive optimism about real estate. Irish housing prices began rising in the 1990s, in part a result of the economy’s strong growth. However, real estate developers began betting on ever-rising prices, and Irish banks were all too willing to lend these developers large amounts of money to back their speculations. Housing prices tripled between 1997 and 2007, home construction quadrupled over the same period, and total credit offered by banks rose far faster than in any other European nation. To raise the cash for their lending spree, Irish banks supplemented the funds of depositors with large amounts of “wholesale” funding—short-term borrowing from other banks and private investors.

In 2007 the real estate boom collapsed. Home prices started falling, and home sales collapsed. Many of the loans that banks had made during the boom went into default. Now, so-called ghost estates, new housing developments full of unoccupied, crumbling homes, dot the landscape. In 2008, the troubles of the Irish banks threatened to turn into a sort of bank-run—not by depositors, but by lenders who had provided the banks with short-term funding through the wholesale interbank lending market. To stabilize the situation, the Irish government stepped in, guaranteeing repayment of all bank debt.

This created a new problem because it put Irish taxpayers on the hook for potentially huge bank losses. Until the crisis struck, Ireland had seemed to be in good fiscal shape, with relatively low government debt and a budget surplus. The banking crisis, however, led to serious questions about the solvency of the Irish government—whether it had the resources to meet its obligations—and forced the government to pay high interest rates on funds it raised in international markets.

Like most banking crises, Ireland’s led to a severe recession. The unemployment rate rose from less than 5% before the crisis to more than 14.8%, where it remained throughout 2012.

Quick Review

- Although individual bank failures are common, a banking crisis is a rare event that typically will severely harm the broader economy.

- A banking crisis can occur because depository or shadow banks invest in an asset bubble or through financial contagion, set off by bank-runs or by a vicious cycle of deleveraging. Largely unregulated, shadow banking is particularly vulnerable to contagion.

- In 2008, an asset bubble combined with a huge shadow banking sector and a vicious cycle of deleveraging created a financial panic and banking crisis, as savers cut their spending and investors hoarded their funds, sending the economy into a steep decline.

- Between the Civil War and the Great Depression, the United States suffered numerous banking crises and financial panics, each followed by a severe economic downturn. The banking reforms of the 1930s prevented another banking crisis until 2008.

- Banking crises usually occur in small, poor countries, although there have been banking crises in advanced countries as well. The fall of Lehman caused a banking crisis and a financial panic in the shadow banking sector, leading investors to shift back into the depository banking sector.

Check Your Understanding 18-2

Question

Regarding the Economics in Action “Erin Go Broke,” where did the asset bubble occur?

A. B. C. The asset bubble occurred in Irish real estate.Question

Regarding the Economics in Action “Erin Go Broke,” which of the following correctly describes the channel of financial contagion?

A. B. C. The channel of the financial contagion was the shortterm lending that Irish banks depended on from the wholesale interbank lending market. When lenders began to worry about the soundness of the Irish banks, they refused to lend any more money, leading to a type of bank-run and putting the Irish banks at great risk of failure.

Question

As described in Economics in Action “Erin Go Broke,” the Irish government tried to stabilize the situation by guaranteeing the debts of the banks. Was this a questionable policy?

A. B. Because the bank-run started with fears among lenders to Irish banks, the Irish government sought to eliminate those fears by guaranteeing the lenders that they would be repaid in full. It was a questionable strategy, though, because it put the Irish taxpayers on the hook for potentially very large losses, so large that they threatened the solvency of the Irish government.

Solutions appear at back of book.