The Consequences of Banking Crises

If banking crises affected only banks, they wouldn’t be as serious a concern. In fact, however, banking crises are almost always associated with recessions, and severe banking crises are associated with the worst economic slumps. Furthermore, history shows that recessions caused in part by banking crises inflict sustained economic damage, with economies taking years to recover.

Banking Crises, Recessions, and Recovery

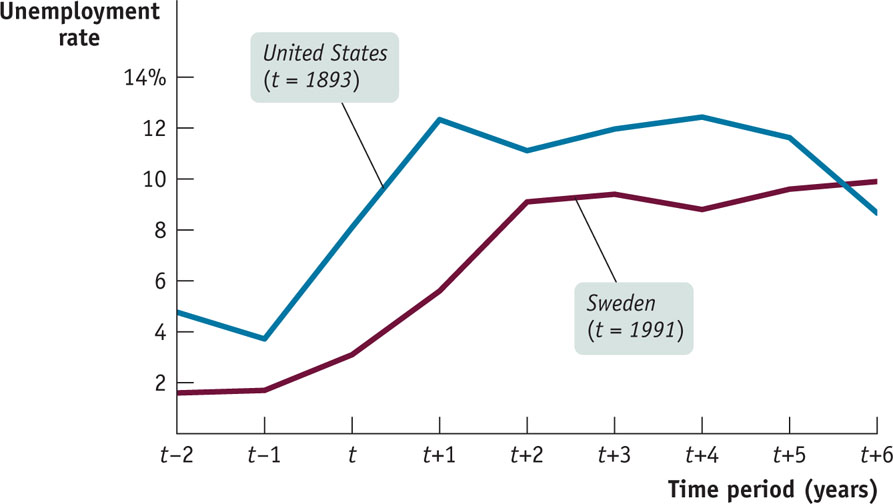

A severe banking crisis is one in which a large fraction of the banking system either fails outright (that is, goes bankrupt) or suffers a major loss of confidence and must be bailed out by the government. Such crises almost invariably lead to deep recessions, which are usually followed by slow recoveries. Figure 18-2 illustrates this phenomenon by tracking unemployment in the aftermath of two banking crises widely separated in space and time: the Panic of 1893 in the United States and the Swedish banking crisis of 1991. In the figure, t represents the year of the crisis: 1893 for the United States, 1991 for Sweden. As the figure shows, these crises on different continents, almost a century apart, produced similarly devastating results: unemployment shot up and came down only slowly and erratically so that, even five years after the crisis, the number of jobless remained high by pre-crisis standards.

FIGURE 18-2 Unemployment Rates, Before and After a Banking Crisis

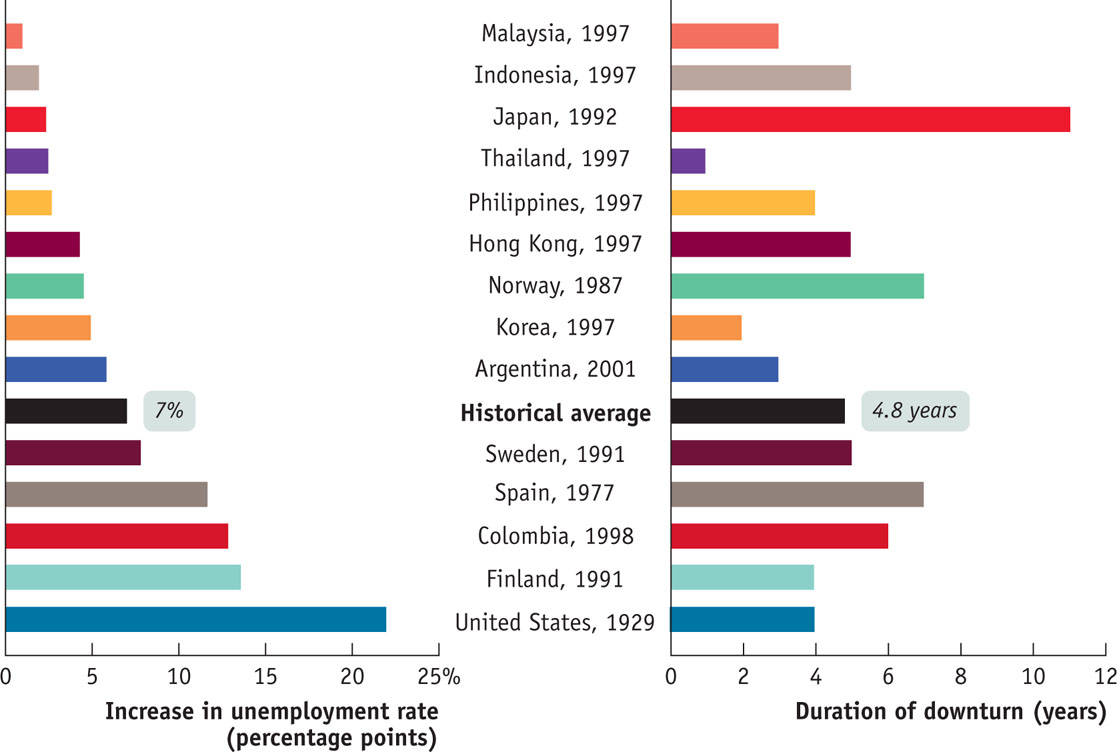

These historical examples are typical. Figure 18-3, taken from a widely cited study by the economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, compares employment performance in the wake of a number of severe banking crises. The bars on the left show the rise in the unemployment rate during and following the crisis; the bars on the right show the time it took before unemployment began to fall. The numbers are shocking: on average, severe banking crises have been followed by a 7 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate, and in many cases it has taken four years or more before the unemployment rate even begins to fall, let alone returns to pre-crisis levels.

FIGURE 18-3 Episodes of Banking Crises and Unemployment

Source: Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff, “The Aftermath of Financial Crises,” American Economic Review 99, no. 2 (2009): 466–472.

Why Are Banking-Crisis Recessions So Bad?

It’s not difficult to see why banking crises normally lead to recessions. There are three main reasons: a credit crunch arising from reduced availability of credit, financial distress caused by a debt overhang, and the loss of monetary policy effectiveness.

- Credit crunch. The disruption of the banking system typically leads to a reduction in the availability of credit called a credit crunch, in which potential borrowers either can’t get credit at all or must pay very high interest rates. Unable to borrow or unwilling to pay higher interest rates, businesses and consumers cut back on spending, pushing the economy into a recession.

In a credit crunch, potential borrowers either can’t get credit at all or must pay very high interest rates.

- Debt overhang. A banking crisis typically pushes down the prices of many assets through a vicious circle of deleveraging, as distressed borrowers try to sell assets to raise cash, pushing down asset prices and causing further financial distress. As we have already seen, deleveraging is a factor in the spread of the crisis, lowering the value of the assets banks hold on their balance sheets and so undermining their solvency. It also creates problems for other players in the economy. To take an example all too familiar from recent events, falling housing prices can leave consumers substantially poorer, especially because they are still stuck with the debt they incurred to buy their homes. A banking crisis, then, tends to leave consumers and businesses with a debt overhang: high debt but diminished assets. Like a credit crunch, this also leads to a fall in spending and a recession as consumers and businesses cut back in order to reduce their debt and rebuild their assets.

A debt overhang occurs when a vicious circle of deleveraging leaves a borrower with high debt but diminished assets.

- Loss of monetary policy effectiveness. A key feature of banking-crisis recessions is that when they occur, monetary policy—the main tool of policy makers for fighting negative demand shocks caused by a fall in consumer and investment spending—loses much of its effectiveness. The ineffectiveness of monetary policy makes banking-crisis recessions especially severe and long-lasting.

Recall how the Fed normally responds to a recession: it engages in open-market operations, purchasing short-term government debt from banks. This leaves banks with excess reserves, which they lend out, leading to a fall in interest rates and causing an economic expansion through increased consumer and investment spending.

Under normal conditions, this policy response is highly effective. In the aftermath of a banking crisis, though, the whole process tends to break down. Banks, fearing runs by depositors or a loss of confidence by their creditors, tend to hold on to excess reserves rather than lend them out. Meanwhile, businesses and consumers, finding themselves in financial difficulty due to the plunge in asset prices, may be unwilling to borrow even if interest rates fall. As a result, even very low interest rates may not be enough to push the economy back to full employment.

The economy is in a liquidity trap when conventional monetary policy is ineffective because nominal interest rates are up against the zero bound.

In Chapter 17 we discussed the fact that interest rates can’t go below zero—called the zero bound for interest rates. A situation in which conventional monetary policy, such as cutting interest rates, can’t be used to fight a slump because nominal interest rates are up against the zero bound is known as a liquidity trap. In fact, all the historical episodes in which the zero bound for interest rates became an important constraint on policy—the 1930s, Japan in the 1990s, and a number of countries after 2008—have occurred after a major banking crisis.

The inability of the usual tools of monetary policy to offset the macroeconomic devastation caused by banking crises is the major reason such crises produce deep, prolonged slumps. The obvious solution is to look for other policy tools. In fact, governments do typically take a variety of special steps when banks are in crisis.

Governments Step In

Before the Great Depression, policy makers often adopted a laissez-faire attitude toward banking crises, allowing banks to fail in the belief that market forces should be allowed to work. Since the catastrophe of the 1930s, though, almost all policy makers have believed that it’s necessary to take steps to contain the damage from bank failures. In general, central banks and governments take three main kinds of action in an effort to limit the fallout from banking crises:

- They act as the lender of last resort.

- They offer guarantees to depositors and others with claims on banks.

- In an extreme crisis, a central bank will step in and provide financing to private credit markets.

A lender of last resort is an institution, usually a country’s central bank, that provides funds to financial institutions when they are unable to borrow from the private credit markets.

1. Lender of Last Resort A lender of last resort is an institution, usually a country’s central bank, that provides funds to financial institutions when they are unable to borrow from the private credit markets. In particular, the central bank can provide cash to a bank that is facing a run by depositors but is fundamentally solvent, making it unnecessary for the bank to engage in fire sales of its assets to raise cash. This acts as a lifeline, working to prevent a loss of confidence in the bank’s solvency from turning into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

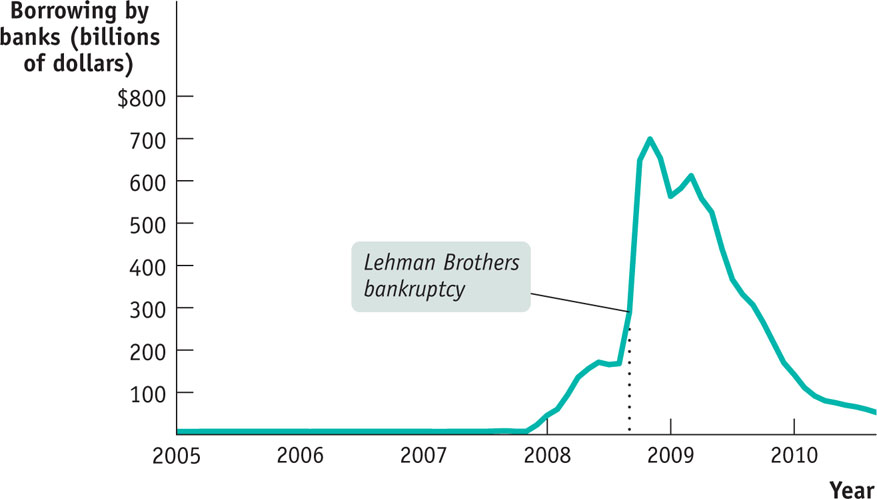

Did the Federal Reserve act as a lender of last resort in the 2008 financial crisis? Very much so. Figure 18-4 shows borrowing by banks from the Fed between 2005 and 2010: commercial banks borrowed negligible amounts from the central bank before the crisis, but their borrowing rose to $700 billion in the months following Lehman’s failure. To get a sense of how large this borrowing was, note that total bank reserves before the crisis were less than $50 billion—so these loans were 14 times the banks’ initial reserves.

FIGURE 18-4 Total Borrowings of Depository Institutions from the Federal Reserve

2. Government Guarantees There are limits, though, to how much a lender of last resort can accomplish: it can’t restore confidence in a bank if there is good reason to believe the bank is fundamentally insolvent. If the public believes that the bank’s assets aren’t worth enough to cover its debts even if it doesn’t have to sell these assets on short notice, a lender of last resort isn’t going to help much. And in major banking crises there are often good reasons to believe that many banks are truly bankrupt.

In such cases, governments often step in to guarantee banks’ liabilities. In 2007, a bank-run hit the British bank, Northern Rock, ceasing only when the British government stepped in and guaranteed all deposits at the bank, regardless of size. Ireland’s government eventually stepped in to guarantee repayment of not just deposits at all of the nation’s banks, but all bank debts. Sweden did the same thing after its 1991 banking crisis.

When governments take on banks’ risk, they often demand a quid pro quo—namely, they often take ownership of the banks they are rescuing. Northern Rock was nationalized in 2008. Sweden nationalized a significant part of its banking system in 1992. In the United States, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation routinely seizes banks that are no longer solvent; it seized 140 banks in 2009. Ireland, however, chose not to seize any of the banks whose debts were guaranteed by taxpayers.

These government takeovers are almost always temporary. In general, modern governments want to save banks, not run them. So they “reprivatize” nationalized banks, selling them to private buyers, as soon as they believe they can.

3. Provider of Direct Financing As we learned in Chapter 16, during the depths of the 2008 financial crisis the Federal Reserve expanded its operations beyond the usual measures of open-market operations and lending to depository banks. It also began lending to shadow banks and buying commercial paper—short-term bonds issued by private companies—as well as buying the debt of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored home mortgage agencies. In this way, the Fed provided credit to keep the economy afloat when private credit markets had dried up.

Banks and the Great Depression

According to the official business-cycle chronology, the United States entered a recession in August 1929, two months before that year’s famous stock market crash. Although the crash surely made the slump worse, through late 1930 it still seemed to be a more or less ordinary recession. Then the bank failures began. A majority of economists believe that the banking crisis is what turned a fairly severe but not catastrophic recession into the Great Depression.

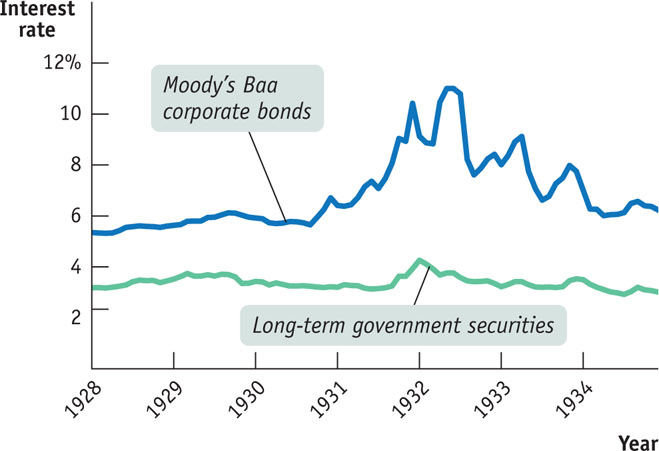

How did the banking crisis hurt the wider economy? Largely by creating a credit crunch, in which businesses in particular either could not borrow or found themselves forced to pay sharply higher interest rates. Figure 18-5 shows one indicator of this credit crunch: the difference between the interest rates—known as the “spread”—at which businesses with good but not great credit could borrow and the borrowing costs of the federal government.

FIGURE 18-5 The 1930s Banking Crisis and Credit Crunch

Baa corporate bonds are those that Moody’s, the credit rating agency, considers “medium-grade obligations”—debts of companies that should be able to pay but aren’t completely reliable. (“Baa” refers to the specific rating assigned to the bonds of such companies.) Until the banking crisis struck, Baa borrowers borrowed at interest rates only about 2 percentage points higher than the interest rates the government borrowed at, and this spread remained low until the summer of 1931. Then it surged, peaking at more than 7 percentage points in 1932. Bear in mind that this is just one indicator of the credit crunch: many would-be borrowers were completely shut out.

One striking fact about the banking crisis of the early 1930s is that the Federal Reserve, although it had the legal ability to act as a lender of last resort, largely failed to do so. Nothing like the surge in bank borrowing from the Fed that took place in 2007–2009 occurred. In fact, bank borrowing from the Fed throughout the 1930s banking crisis was at levels lower than those reached in 1928–1929.

Meanwhile, neither the Fed nor the federal government did anything to rescue failing banks until 1933. So the early 1930s offer a clear example of a banking crisis that policy makers more or less allowed to take its course. It’s not an experience anyone wants to repeat.

Quick Review

- Banking crises almost always result in recessions, with severe banking crises associated with the worst economic slumps. Historically, severe banking crises have resulted, on average, in a 7-percentage-point rise in the unemployment rate.

- Recessions caused by banking crises are especially severe because they involve a credit crunch, a vicious circle of deleveraging coupled with a debt overhang, leading households and businesses to cut spending, further deepening the downturn.

- Slumps induced by bank crises are so severe and prolonged because they make monetary policy ineffective: even though the central bank can lower interest rates, financially distressed households and businesses may still be unwilling to borrow and spend. An economy is in a liquidity trap when conventional monetary policy is ineffective because nominal interest rates are up against the zero bound.

- Central banks and governments use two main types of policies to limit the damage from a banking crisis: acting as the lender of last resort and offering guarantees that the banks’ liabilities will be repaid. In the aftermath of a bank rescue, governments sometimes nationalize the bank and then later reprivatize it. In an extreme crisis, the central bank will provide direct financing to private credit markets.

Check Your Understanding 18-3

Question

True or False? The Federal Reserve was able to prevent a replay of the Great Depression because, as in the 1930s, it acted as a lender of last resort to stabilize the banking sector and halt the contagion.

A. B. False. The Federal Reserve was able to prevent a replay of the Great Depression because, unlike in the 1930s, it acted as a lender of last resort to stabilize the banking sector and halt the contagion. But it was unable to significantly reduce the surge in unemployment because the United States experienced a credit crunch and a vicious circle of deleveraging, leaving monetary policy relatively ineffective.Question

True or False? A very low interest rate—even as low as 0%—may be unable to move the economy back to full employment.

A. B. True. In the aftermath of a severe banking crisis, businesses and households have high debt and reduced assts. They cut back on spending to try to reduce their debt. So they are unwilling to borrow regardless of how low the interest rate is.

Solutions appear at back of book.