Supply, Demand, and International Trade

Simple models of comparative advantage are helpful for understanding the fundamental causes of international trade. However, to analyze the effects of international trade at a more detailed level and to understand trade policy, it helps to return to the supply and demand model. We’ll start by looking at the effects of imports on domestic producers and consumers, then turn to the effects of exports.

The Effects of Imports

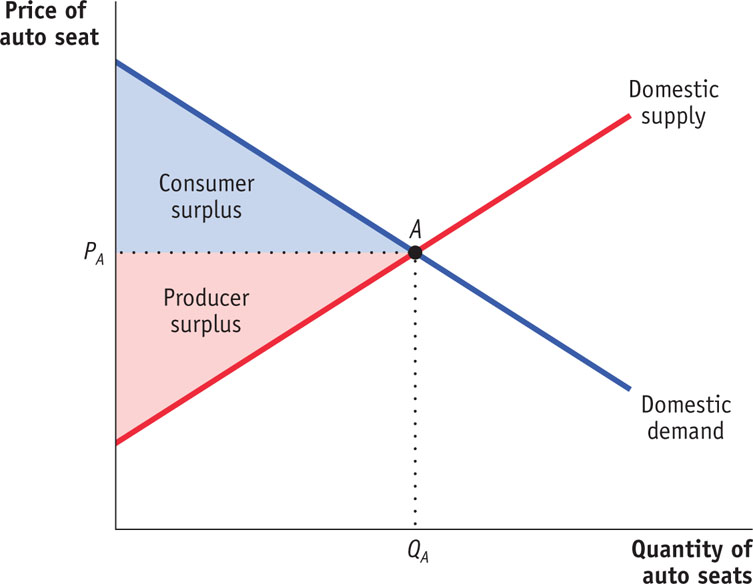

Figure 19-5 shows the U.S. market for auto seats, ignoring international trade for a moment. It introduces a few new concepts: the domestic demand curve, the domestic supply curve, and the domestic or autarky price.

FIGURE 19-5 Consumer and Producer Surplus in Autarky

The domestic demand curve shows how the quantity of a good demanded by domestic consumers depends on the price of that good.

The domestic supply curve shows how the quantity of a good supplied by domestic producers depends on the price of that good.

The domestic demand curve shows how the quantity of a good demanded by residents of a country depends on the price of that good. Why “domestic”? Because people living in other countries may demand the good, too. Once we introduce international trade, we need to distinguish between purchases of a good by domestic consumers and purchases by foreign consumers. So the domestic demand curve reflects only the demand of residents of our own country. Similarly, the domestic supply curve shows how the quantity of a good supplied by producers inside our own country depends on the price of that good. Once we introduce international trade, we need to distinguish between the supply of domestic producers and foreign supply—supply brought in from abroad.

In autarky, with no international trade in auto seats, the equilibrium in this market would be determined by the intersection of the domestic demand and domestic supply curves, point A. The equilibrium price of auto seats would be PA, and the equilibrium quantity of auto seats produced and consumed would be QA. As always, both consumers and producers gain from the existence of the domestic market. In autarky, consumer surplus would be equal to the area of the blue-shaded triangle in Figure 19-5. Producer surplus would be equal to the area of the red-shaded triangle. And total surplus would be equal to the sum of these two shaded triangles.

The world price of a good is the price at which that good can be bought or sold abroad.

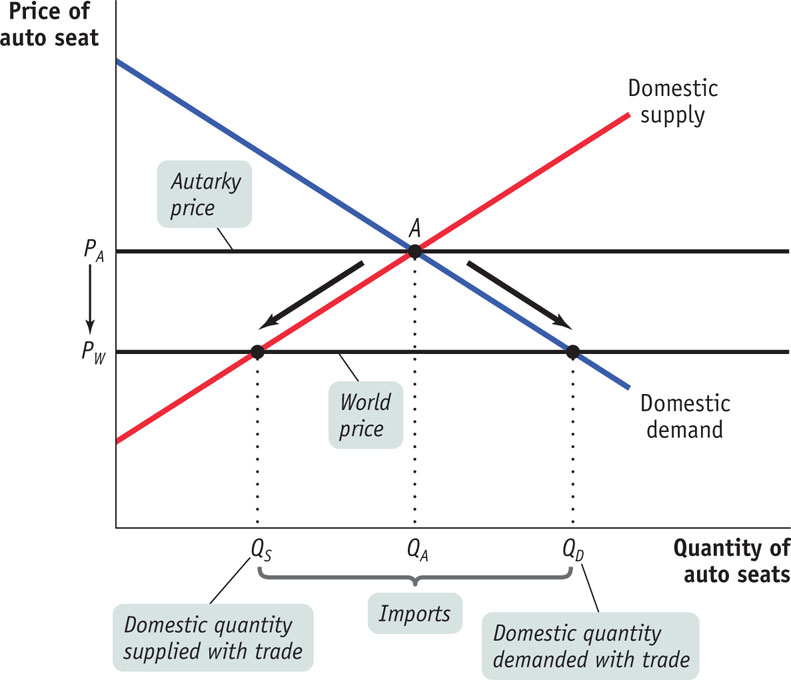

Now let’s imagine opening up this market to imports. To do this, we must make an assumption about the supply of imports. The simplest assumption, which we will adopt here, is that unlimited quantities of auto seats can be purchased from abroad at a fixed price, known as the world price of auto seats. Figure 19-6 shows a situation in which the world price of an auto seat, PW, is lower than the price of an auto seat that would prevail in the domestic market in autarky, PA.

FIGURE 19-6 The Domestic Market with Imports

Given that the world price is below the domestic price of an auto seat, it is profitable for importers to buy auto seats abroad and resell them domestically. The imported auto seats increase the supply of auto seats in the domestic market, driving down the domestic market price. Auto seats will continue to be imported until the domestic price falls to a level equal to the world price.

The result is shown in Figure 19-6. Because of imports, the domestic price of an auto seat falls from PA to PW. The quantity of auto seats demanded by domestic consumers rises from QA to QD, and the quantity supplied by domestic producers falls from QA to QS. The difference between the domestic quantity demanded and the domestic quantity supplied, QD − QS, is filled by imports.

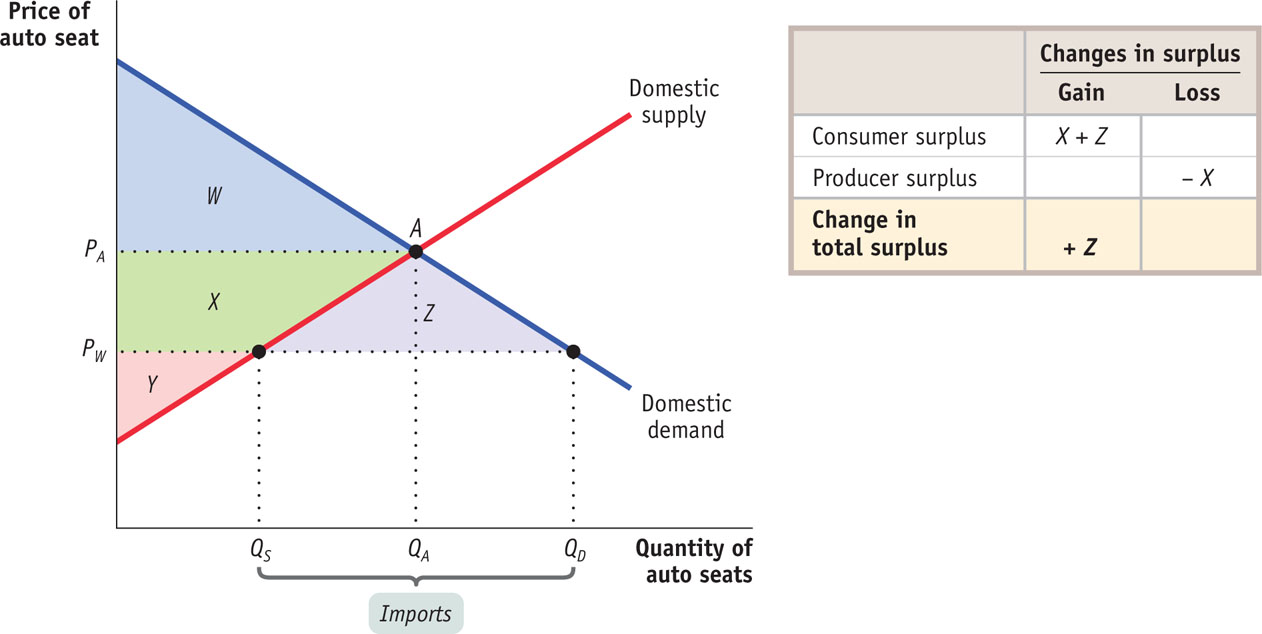

Now let’s turn to the effects of imports on consumer surplus and producer surplus. Because imports of auto seats lead to a fall in their domestic price, consumer surplus rises and producer surplus falls. Figure 19-7 shows how this works. We label four areas: W, X, Y, and Z. The autarky consumer surplus we identified in Figure 19-5 corresponds to W, and the autarky producer surplus corresponds to the sum of X and Y. The fall in the domestic price to the world price leads to an increase in consumer surplus; it increases by X and Z, so consumer surplus now equals the sum of W, X, and Z. At the same time, producers lose X in surplus, so producer surplus now equals only Y.

FIGURE 19-7 The Effects of Imports on Surplus

The table in Figure 19-7 summarizes the changes in consumer and producer surplus when the auto seats market is opened to imports. Consumers gain surplus equal to the areas X + Z. Producers lose surplus equal to X. So the sum of producer and consumer surplus—the total surplus generated in the auto seats market—increases by Z. As a result of trade, consumers gain and producers lose, but the gain to consumers exceeds the loss to producers.

This is an important result. We have just shown that opening up a market to imports leads to a net gain in total surplus, which is what we should have expected given the proposition that there are gains from international trade. However, we have also learned that although the country as a whole gains, some groups—in this case, domestic producers of auto parts—lose as a result of international trade. As we’ll see shortly, the fact that international trade typically creates losers as well as winners is crucial for understanding the politics of trade policy.

We turn next to the case in which a country exports a good.

The Effects of Exports

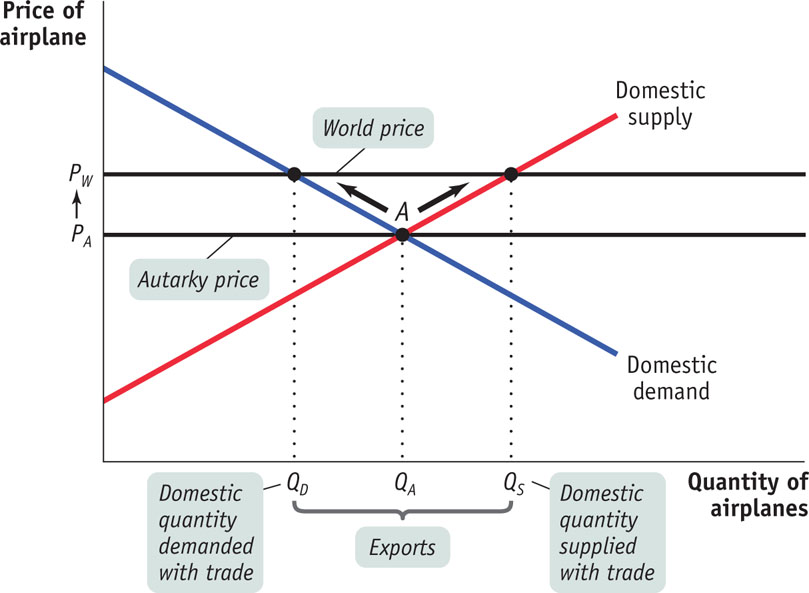

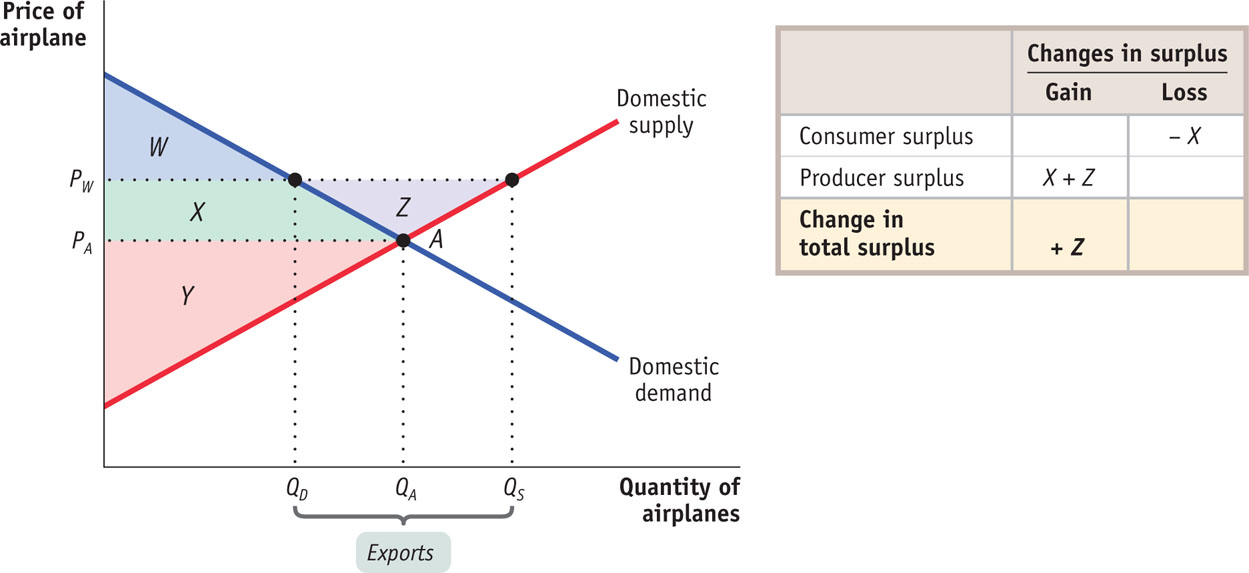

Figure 19-8 shows the effects on a country when it exports a good, in this case airplanes. For this example, we assume that unlimited quantities of airplanes can be sold abroad at a given world price, PW, which is higher than the price that would prevail in the domestic market in autarky, PA.

FIGURE 19-8 The Domestic Market with Exports

The higher world price makes it profitable for exporters to buy airplanes domestically and sell them overseas. The purchases of domestic airplanes drive the domestic price up until it is equal to the world price. As a result, the quantity demanded by domestic consumers falls from QA to QD and the quantity supplied by domestic producers rises from QA to QS. This difference between domestic production and domestic consumption, QS – QD, is exported.

Like imports, exports lead to an overall gain in total surplus for the exporting country but also create losers as well as winners. Figure 19-9 shows the effects of airplane exports on producer and consumer surplus. In the absence of trade, the price of each airplane would be PA. Consumer surplus in the absence of trade is the sum of areas W and X, and producer surplus is area Y. As a result of trade, price rises from PA to PW, consumer surplus falls to W, and producer surplus rises to Y + X + Z. So producers gain X + Z, consumers lose X, and, as shown in the table accompanying the figure, the economy as a whole gains total surplus in the amount of Z.

FIGURE 19-9 The Effects of Exports on Surplus

We have learned, then, that imports of a particular good hurt domestic producers of that good but help domestic consumers, whereas exports of a particular good hurt domestic consumers of that good but help domestic producers. In each case, the gains are larger than the losses.

International Trade and Wages

So far we have focused on the effects of international trade on producers and consumers in a particular industry. For many purposes this is a very helpful approach. However, producers and consumers are not the only parts of society affected by trade—so are the owners of factors of production. In particular, the owners of labor, land, and capital employed in producing goods that are exported, or goods that compete with imported goods, can be deeply affected by trade.

Moreover, the effects of trade aren’t limited to just those industries that export or compete with imports because factors of production can often move between industries. So now we turn our attention to the long-run effects of international trade on income distribution—how a country’s total income is allocated among its various factors of production.

To begin our analysis, consider the position of Maria, an accountant at Midwest Auto Parts, Inc. If the economy is opened up to imports of auto parts from Mexico, the domestic auto parts industry will contract, and it will hire fewer accountants. But accounting is a profession with employment opportunities in many industries, and Maria might well find a better job in the aircraft industry, which expands as a result of international trade. So it may not be appropriate to think of her as a producer of auto parts who is hurt by competition from imported parts. Rather, we should think of her as an accountant who is affected by auto part imports only to the extent that these imports change the wages of accountants in the economy as a whole.

The wage rate of accountants is a factor price—the price employers have to pay for the services of a factor of production. One key question about international trade is how it affects factor prices—not just narrowly defined factors of production like accountants, but broadly defined factors such as capital, unskilled labor, and college-educated labor.

Earlier in this chapter we described the Heckscher–Ohlin model of trade, which states that comparative advantage is determined by a country’s factor endowment. This model also suggests how international trade affects factor prices in a country: compared to autarky, international trade tends to raise the prices of factors that are abundantly available and reduce the prices of factors that are scarce.

We won’t work this out in detail, but the idea is simple. The prices of factors of production, like the prices of goods and services, are determined by supply and demand. If international trade increases the demand for a factor of production, that factor’s price will rise; if international trade reduces the demand for a factor of production, that factor’s price will fall.

Exporting industries produce goods and services that are sold abroad.

Import-competing industries produce goods and services that are also imported.

Now think of a country’s industries as consisting of two kinds: exporting industries, which produce goods and services that are sold abroad, and import-competing industries, which produce goods and services that are also imported from abroad. Compared with autarky, international trade leads to higher production in exporting industries and lower production in import-competing industries. This indirectly increases the demand for the factors used by exporting industries and decreases the demand for factors used by import-competing industries.

In addition, the Heckscher–Ohlin model says that a country tends to export goods that are intensive in its abundant factors and to import goods that are intensive in its scarce factors. So international trade tends to increase the demand for factors that are abundant in our country compared with other countries, and to decrease the demand for factors that are scarce in our country compared with other countries. As a result, the prices of abundant factors tend to rise, and the prices of scarce factors tend to fall as international trade grows. In other words, international trade tends to redistribute income toward a country’s abundant factors and away from its less abundant factors.

The Economics in Action at the end of the preceding section pointed out that U.S. exports tend to be human-capital-intensive and U.S. imports tend to be unskilled-labor-intensive. This suggests that the effect of international trade on U.S. factor markets is to raise the wage rate of highly educated American workers and reduce the wage rate of unskilled American workers.

This effect has been a source of much concern in recent years. Wage inequality—the gap between the wages of high-paid and low-paid workers—has increased substantially over the last 30 years. Some economists believe that growing international trade is an important factor in that trend. If international trade has the effects predicted by the Heckscher–Ohlin model, its growth raises the wages of highly educated American workers, who already have relatively high wages, and lowers the wages of less educated American workers, who already have relatively low wages. But keep in mind another phenomenon: trade reduces the income inequality between countries as poor countries improve their standard of living by exporting to rich countries.

How important are these effects? In some historical episodes, the impacts of international trade on factor prices have been very large. As we explain in the following Economics in Action, the opening of transatlantic trade in the late nineteenth century had a large negative impact on land rents in Europe, hurting landowners but helping workers and owners of capital.

The effects of trade on wages in the United States have generated considerable controversy in recent years. Most economists who have studied the issue agree that growing imports of labor-intensive products from newly industrializing economies, and the export of high-technology goods in return, have helped cause a widening wage gap between highly educated and less educated workers in this country. However, most economists believe that it is only one of several forces explaining the growth in American wage inequality.

Trade, Wages, and Land Prices in the Nineteenth Century

Beginning around 1870, there was an explosive growth of world trade in agricultural products, based largely on the steam engine. Steam-powered ships could cross the ocean much more quickly and reliably than sailing ships. Until about 1860, steamships had higher costs than sailing ships, but after that costs dropped sharply. At the same time, steam-powered rail transport made it possible to bring grain and other bulk goods cheaply from the interior to ports. The result was that land-abundant countries—the United States, Canada, Argentina, and Australia—began shipping large quantities of agricultural goods to the densely populated, land-scarce countries of Europe.

This opening up of international trade led to higher prices of agricultural products, such as wheat, in exporting countries and a decline in their prices in importing countries. Notably, the difference between wheat prices in the midwestern United States and England plunged.

The change in agricultural prices created winners and losers on both sides of the Atlantic as factor prices adjusted. In England, land prices fell by half compared with average wages; landowners found their purchasing power sharply reduced, but workers benefited from cheaper food. In the United States, the reverse happened: land prices doubled compared with wages. Landowners did very well, but workers found the purchasing power of their wages dented by rising food prices.

Quick Review

- The intersection of the domestic demand curve and the domestic supply curve determines the domestic price of a good. When a market is opened to international trade, the domestic price is driven to equal the world price.

- If the world price is lower than the autarky price, trade leads to imports and the domestic price falls to the world price. There are overall gains from international trade because the gain in consumer surplus exceeds the loss in producer surplus.

- If the world price is higher than the autarky price, trade leads to exports and the domestic price rises to the world price. There are overall gains from international trade because the gain in producer surplus exceeds the loss in consumer surplus.

- Trade leads to an expansion of exporting industries, which increases demand for a country’s abundant factors, and a contraction of import-competing industries, which decreases demand for its scarce factors.

Check Your Understanding 19-2

Question

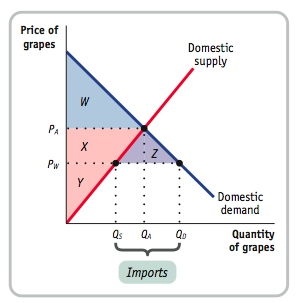

Due to a strike by truckers, trade in food between the United States and Mexico is halted. In autarky, the price of Mexican grapes is lower than that of U.S. grapes. Which of the following explains the effect of this on U.S. grape consumers’ surplus?

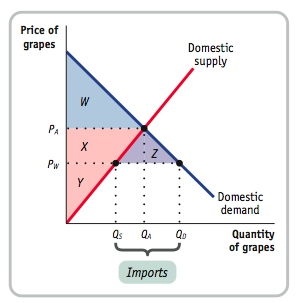

A. B. In the accompanying diagram, PA is the U.S. price of grapes in autarky andPW is the world price of grapes under international trade. With trade, U.S. consumers pay a price of PW for grapes and consume quantity QD, U.S. grape producers produce quantity QS, and the difference, QD − QS, represents imports of Mexican grapes. As a consequence of the strike by truckers, imports are halted, the price paid by American consumers rises to the autarky price, PA, and U.S. consumption falls to the autarky quantity, QA.

Before the strike, U.S. consumers enjoyed consumer surplus equal to areas W + X + Z. After the strike, their consumer surplus shrinks to W. So consumers are worse off, losing consumer surplus represented by X + Z.Question

Due to a strike by truckers, trade in food between the United States and Mexico is halted. In autarky, the price of Mexican grapes is lower than that of U.S. grapes. Which of the following explains the effect of this on U.S. grape producers’ surplus?

A. B. Before the strike, U.S. producers had producer surplus equal to the area Y. After the strike, their producer surplus increases to Y + X. So U.S. producers are better off, gaining producer surplus represented by X.

Question

Due to a strike by truckers, trade in food between the United States and Mexico is halted. In autarky, the price of Mexican grapes is lower than that of U.S. grapes. Which of the following explains the effect of this on U.S. total surplus?

A. B. U.S. total surplus falls as a result of the strike by an amount represented by area Z, the loss in consumer surplus that does not accrue to producers.

Solutions appear at back of book.