The Effects of Trade Protection

An economy has free trade when the government does not attempt either to reduce or to increase the levels of exports and imports that occur naturally as a result of supply and demand.

Policies that limit imports are known as trade protection or simply as protection.

Ever since David Ricardo laid out the principle of comparative advantage in the early nineteenth century, most economists have advocated free trade. That is, they have argued that government policy should not attempt either to reduce or to increase the levels of exports and imports that occur naturally as a result of supply and demand. Despite the free-trade arguments of economists, however, many governments use taxes and other restrictions to limit imports. Less frequently, governments offer subsidies to encourage exports. Policies that limit imports, usually with the goal of protecting domestic producers in import-competing industries from foreign competition, are known as trade protection or simply as protection.

Let’s look at the two most common protectionist policies, tariffs and import quotas, then turn to the reasons governments follow these policies.

The Effects of a Tariff

A tariff is a tax levied on imports.

A tariff is a form of excise tax, one that is levied only on sales of imported goods. For example, the U.S. government could declare that anyone bringing in auto seats must pay a tariff of $100 per unit. In the distant past, tariffs were an important source of government revenue because they were relatively easy to collect. But in the modern world, tariffs are usually intended to discourage imports and protect import-competing domestic producers rather than as a source of government revenue.

The tariff raises both the price received by domestic producers and the price paid by domestic consumers. Suppose, for example, that our country imports auto seats, and an auto seat costs $200 on the world market. As we saw earlier, under free trade the domestic price would also be $200. But if a tariff of $100 per unit is imposed, the domestic price will rise to $300, because it won’t be profitable to import auto seats unless the price in the domestic market is high enough to compensate importers for the cost of paying the tariff.

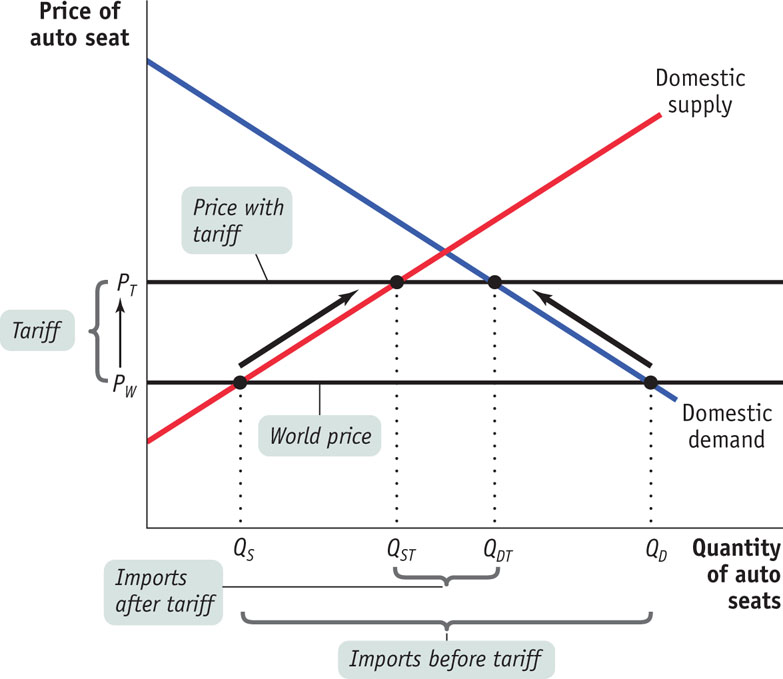

Figure 19-10 illustrates the effects of a tariff on imports of auto seats. As before, we assume that PW is the world price of an auto seat. Before the tariff is imposed, imports have driven the domestic price down to PW, so that pre-tariff domestic production is QS, pre-tariff domestic consumption is QD, and pre-tariff imports are QD − QS.

FIGURE 19-10 The Effect of a Tariff

Now suppose that the government imposes a tariff on each auto seat imported. As a consequence, it is no longer profitable to import auto seats unless the domestic price received by the importer is greater than or equal to the world price plus the tariff. So the domestic price rises to PT, which is equal to the world price, PW, plus the tariff. Domestic production rises to QST, domestic consumption falls to QDT, and imports fall to QDT − QST.

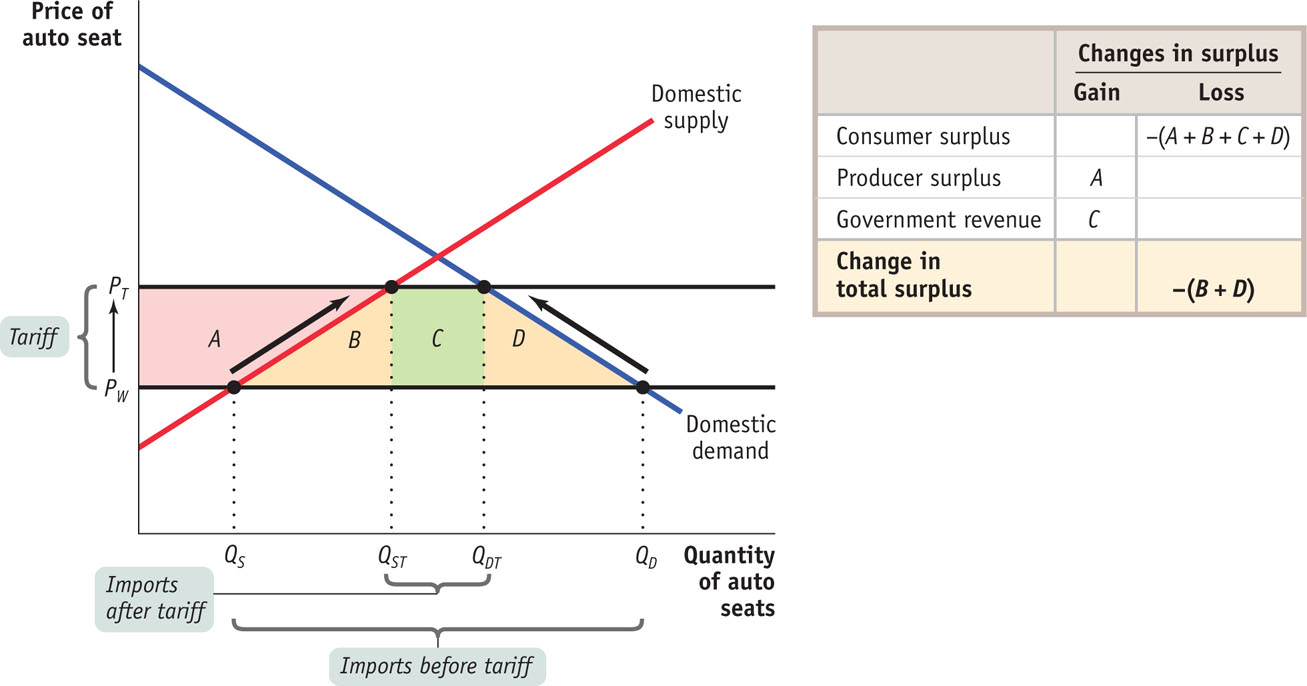

A tariff, then, raises domestic prices, leading to increased domestic production and reduced domestic consumption compared to the situation under free trade. Figure 19-11 shows the effects on surplus. There are three effects:

- The higher domestic price increases producer surplus, a gain equal to area A.

- The higher domestic price reduces consumer surplus, a reduction equal to the sum of areas A, B, C, and D.

- The tariff yields revenue to the government. How much revenue? The government collects the tariff—which, remember, is equal to the difference between PT and PW on each of the QDT − QST units imported. So total revenue is (PT − PW) × (QDT − QST). This is equal to area C.

FIGURE 19-11 A Tariff Reduces Total Surplus

The welfare effects of a tariff are summarized in the table in Figure 19-11. Producers gain, consumers lose, and the government gains. But consumer losses are greater than the sum of producer and government gains, leading to a net reduction in total surplus equal to areas B + D.

An excise tax creates inefficiency, or deadweight loss, because it prevents mutually beneficial trades from occurring. The same is true of a tariff, where the deadweight loss imposed on society is equal to the loss in total surplus represented by areas B + D.

Tariffs generate deadweight losses because they create inefficiencies in two ways:

- Some mutually beneficial trades go unexploited: some consumers who are willing to pay more than the world price, PW, do not purchase the good, even though PW is the true cost of a unit of the good to the economy. The cost of this inefficiency is represented in Figure 19-11 by area D.

- The economy’s resources are wasted on inefficient production: some producers whose cost exceeds PW produce the good, even though an additional unit of the good can be purchased abroad for PW. The cost of this inefficiency is represented in Figure 19-11 by area B.

The Effects of an Import Quota

An import quota is a legal limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported.

An import quota, another form of trade protection, is a legal limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported. For example, a U.S. import quota on Mexican auto seats might limit the quantity imported each year to 500,000 units. Import quotas are usually administered through licenses: a number of licenses are issued, each giving the license-holder the right to import a limited quantity of the good each year.

A quota on sales has the same effect as an excise tax, with one difference: the money that would otherwise have accrued to the government as tax revenue under an excise tax becomes license-holders’ revenue under a quota—also known as quota rents. Similarly, an import quota has the same effect as a tariff, with one difference: the money that would otherwise have been government revenue becomes quota rents to license-holders. Look again at Figure 19-11. An import quota that limits imports to QDT − QST will raise the domestic price of auto parts by the same amount as the tariff we considered previously. That is, it will raise the domestic price from PW to PT. However, area C will now represent quota rents rather than government revenue.

Who receives import licenses and so collects the quota rents? In the case of U.S. import protection, the answer may surprise you: the most important import licenses—mainly for clothing, to a lesser extent for sugar—are granted to foreign governments.

Because the quota rents for most U.S. import quotas go to foreigners, the cost to the nation of such quotas is larger than that of a comparable tariff (a tariff that leads to the same level of imports). In Figure 19-11 the net loss to the United States from such an import quota would be equal to areas B + C + D, the difference between consumer losses and producer gains.

Trade Protection in the United States

The United States today generally follows a policy of free trade, both in comparison with other countries and in comparison with its own history. Most imports are subject to either no tariff or to a low tariff. So what are the major exceptions to this rule?

Most of the remaining protection involves agricultural products. Topping the list is ethanol, which in the United States is mainly produced from corn and used as an ingredient in motor fuel. Most imported ethanol is subject to a fairly high tariff, but some countries are allowed to sell a limited amount of ethanol in the United States, at high prices, without paying the tariff. Dairy products also receive substantial import protection, again through a combination of tariffs and quotas.

Until a few years ago, clothing and textiles were also strongly protected from import competition, thanks to an elaborate system of import quotas. However, this system was phased out in 2005 as part of a trade agreement reached a decade earlier. Some clothing imports are still subject to relatively high tariffs, but protection in the clothing industry is a shadow of what it used to be.

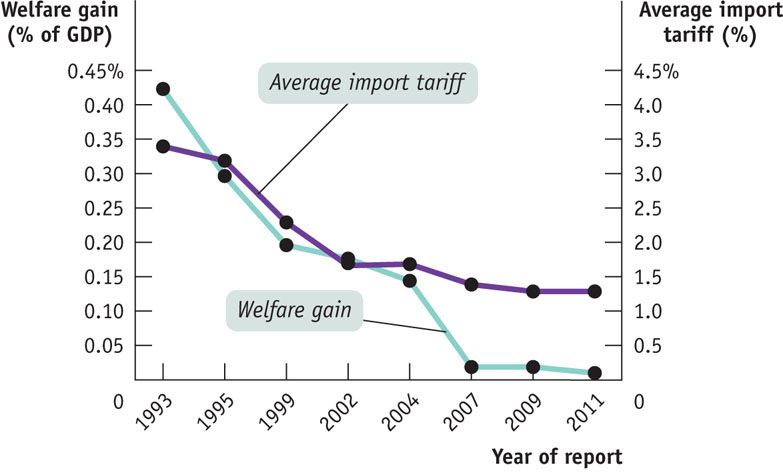

The most important thing to know about current U.S. trade protection is how limited it really is, and how little cost it imposes on the economy. Every two years the U.S. International Trade Commission, a government agency, produces estimates of the impact of “significant trade restrictions” on U.S. welfare. As Figure 19-12 shows, over the past two decades both average tariff levels and the cost of trade restrictions as a share of national income, which weren’t all that big to begin with, have fallen sharply.

FIGURE 19-12 Tariff Rates and Estimated Welfare Gains, 1993–2011

Quick Review

- Most economists advocate free trade, although many governments engage in trade protection of import-competing industries. The two most common protectionist policies are tariffs and import quotas. In rare instances, governments subsidize exporting industries.

- A tariff is a tax on imports. It raises the domestic price above the world price, leading to a fall in trade and domestic consumption and a rise in domestic production. Domestic producers and the government gain, but domestic consumer losses more than offset this gain, leading to deadweight loss.

- An import quota is a legal quantity limit on imports. Its effect is like that of a tariff, except that revenues—the quota rents—accrue to the license-holder, not to the domestic government.

Check Your Understanding 19-3

Question

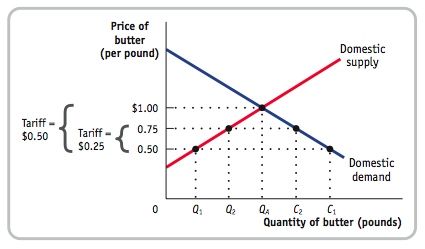

Suppose the world price of butter is $0.50 per pound and the domestic price in autarky is $1.00 per pound.

True or False? If there is free trade, domestic butter producers want the government to impose a tariff of no less than $0.50 per pound.A. B. False. If the tariff is $0.50, the price paid by domestic consumers for a pound of imported butter is $0.50 + $0.50 = $1.00, the same price as a pound of domestic butter. Imported butter will no longer have a price advantage over domestic butter, imports will cease, and domestic producers will capture all the feasible sales to domestic consumers, selling amount QA in the accompanying figure. But if the tariff is less than $0.50—say, only $0.25—the price paid by domestic consumers for a pound of imported butter is $0.50 + $0.25 = $0.75, $0.25 cheaper than a pound of domestic butter. American butter producers will gain sales in the amount of Q2 - Q1 as a result of the $0.25 tariff. But this is smaller than the amount they would have gained under the $0.50 tariff, the amount QA - Q1.

Question

Suppose the world price of butter is $0.50 per pound and the domestic price in autarky is $1.00 per pound. What happens if a tariff greater than $0.50 per pound is imposed?

A. B. As long as the tariff is at least $0.50, increasing it more has no effect. At a tariff of $0.50, all imports are effectively blocked.

Question

Suppose the world price of butter is $0.50 per pound and the domestic price in autarky is $1.00 per pound. Suppose the government imposes an import quota rather than a tariff on butter. What quota limit would generate the same quantity of imports as a tariff of $0.50 per pound?

A. B. C. D. All imports are effectively blocked at a tariff of $0.50. So such a tariff corresponds to an import quota of 0.

Solutions appear at back of book.