The Gains from Trade

Let’s return to the market in used textbooks, but now consider a much bigger market—say, one at a large state university. There are many potential buyers and sellers, so the market is competitive. Let’s line up incoming students who are potential buyers of a book in order of their willingness to pay, so that the entering student with the highest willingness to pay is potential buyer number 1, the student with the next highest willingness to pay is number 2, and so on. Then we can use their willingness to pay to derive a demand curve like the one in Figure 4-5.

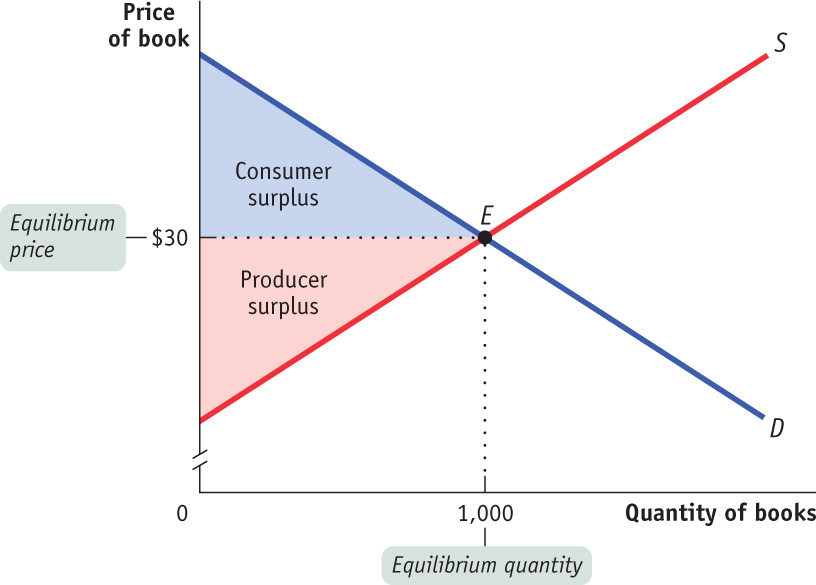

FIGURE 4-5 Total Surplus

Similarly, we can line up outgoing students, who are potential sellers of the book, in order of their cost—starting with the student with the lowest cost, then the student with the next lowest cost, and so on—to derive a supply curve like the one shown in the same figure.

The total surplus generated in a market is the total net gain to consumers and producers from trading in the market. It is the sum of the consumer and the producer surplus.

As we have drawn the curves, the market reaches equilibrium at a price of $30 per book, and 1,000 books are bought and sold at that price. The two shaded triangles show the consumer surplus (blue) and the producer surplus (red) generated by this market. The sum of consumer and producer surplus is known as the total surplus generated in a market.

Take the Keys, Please

Without doubt, history books (or digital readers) will one day cite eBay, the online auction service, as one of the great American innovations of the twentieth century. Founded in 1995, the company says that its mission is “to help practically anyone trade practically anything on earth.” It provides a way for would-be buyers and would-be sellers—sometimes of unique or used items—to find one another. And the gains from trade accruing to eBay users were evidently large: in 2010, eBay reported $53.5 billion in goods bought and sold on its websites.

And the online matching hasn’t stopped there. Websites are now popping up that allow people to rent out their personal possessions—items like cars, power tools, personal electronics, and spare bedrooms. Similar to what eBay did for buyers and sellers, these new websites provide a platform for renters and owners to find one another.

A recent Business Week article describes how one Boston couple used the website RelayRides to rent out a car that had been sitting around largely unused, earning enough to pay for its upkeep and insurance. And according to the founder of RelayRides, Shelby Clark, the average car renter on his website earns $250 per month.

Judith Chevalier, a Yale School of Management economist says, “These companies let you wring a little bit of value out of … goods that are just sitting there.”

RelayRides and companies like it are hoping that they can earn a nice return by helping you generate a little bit more surplus from your possessions.

Quick Review

- Individual consumer surplus is the net gain to an individual consumer from buying a good.

- The total consumer surplus in a given market is equal to the area under the market demand curve but above the price.

- The difference between the price and cost is the seller’s individual producer surplus.

- The total producer surplus is equal to the area above the market supply curve but below the price.

- Total surplus measures the gains from trade in a market.

Check Your Understanding 4-1

Question

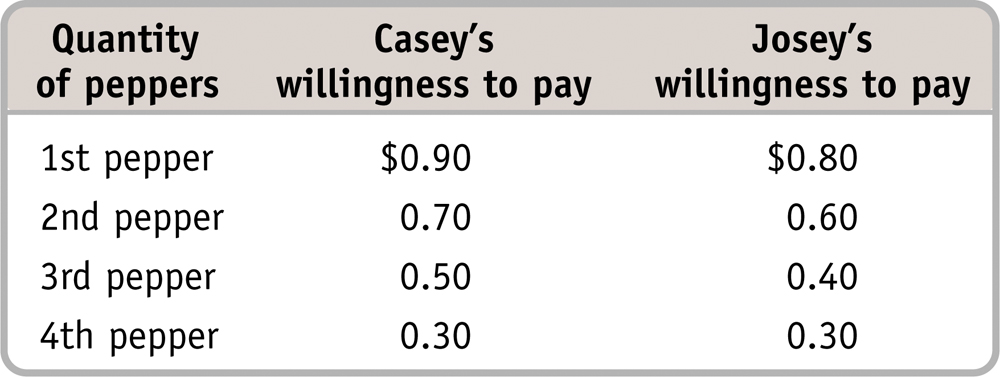

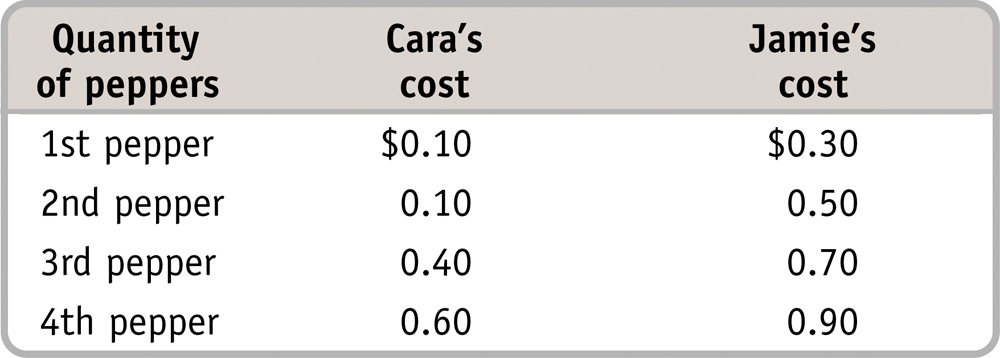

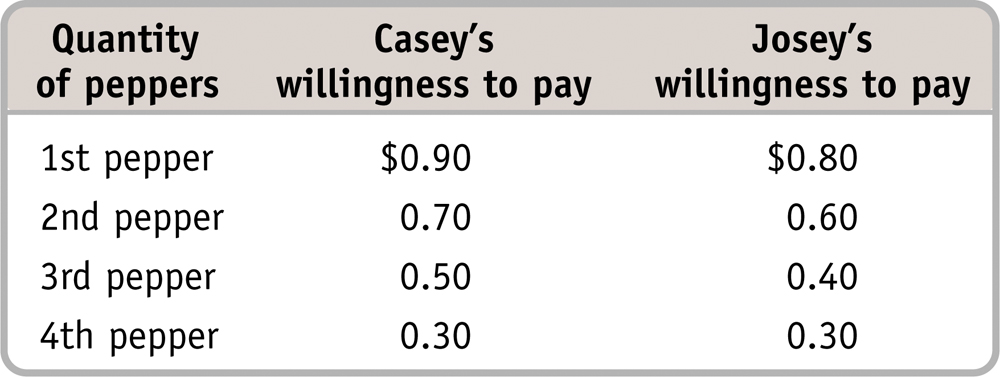

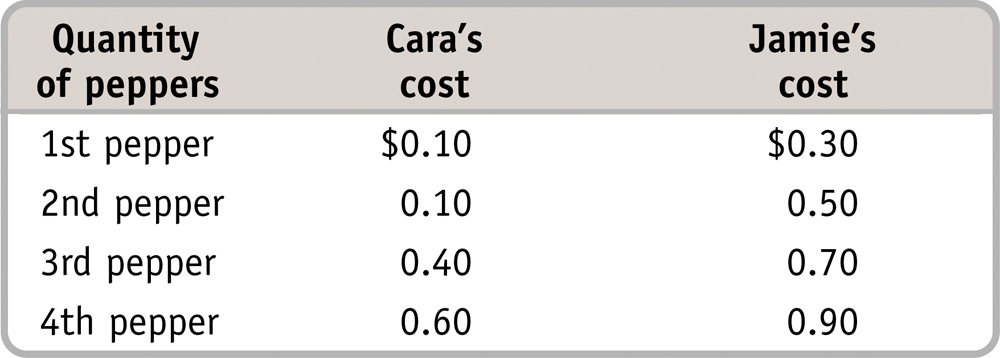

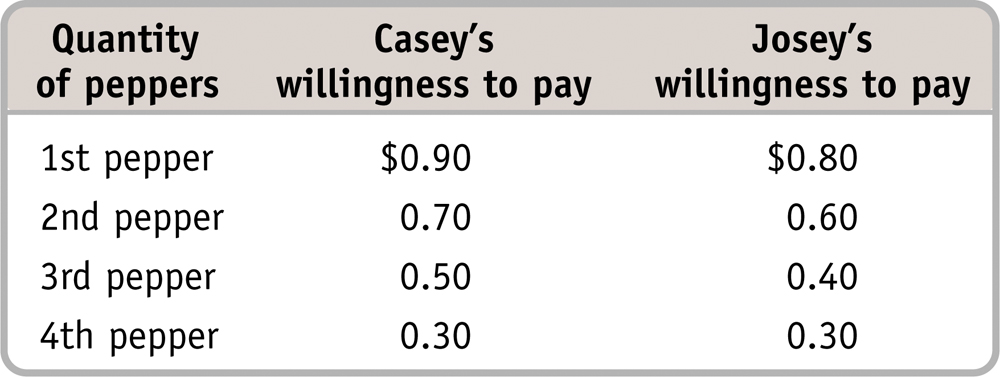

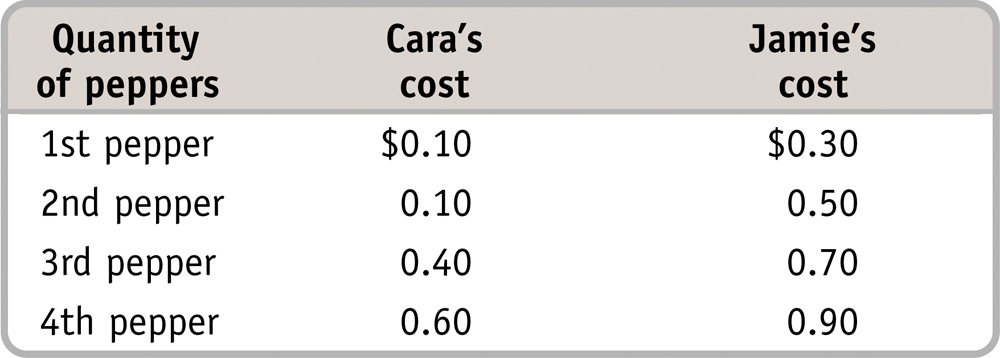

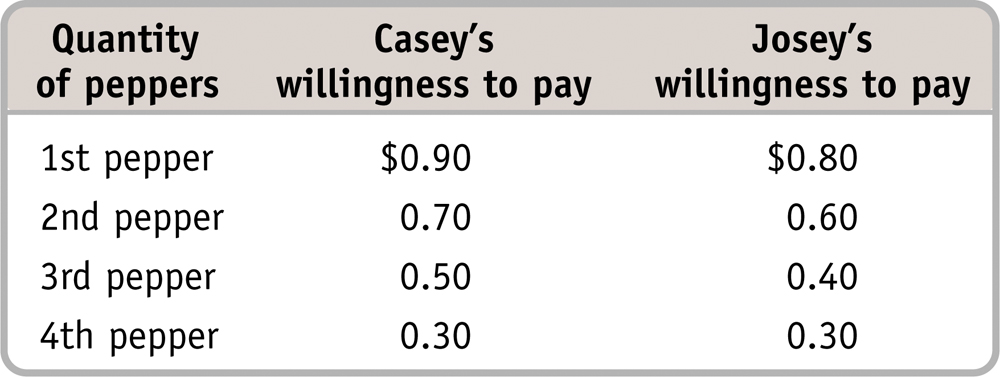

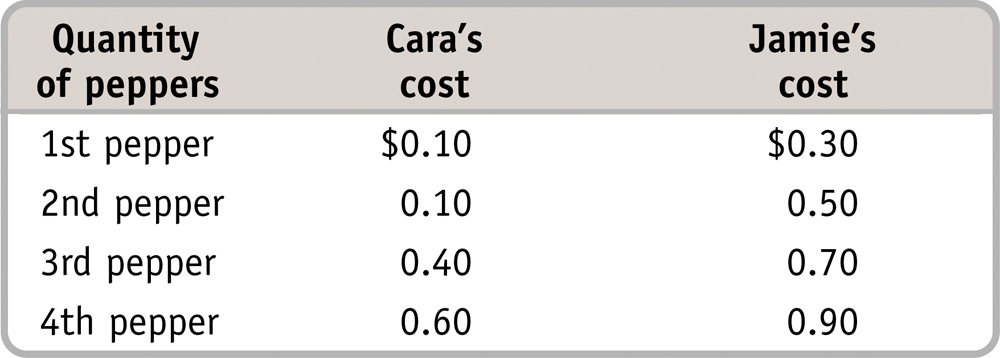

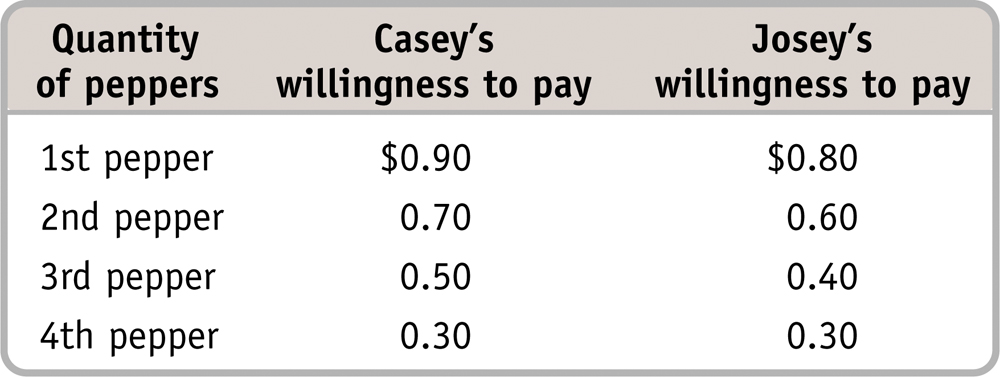

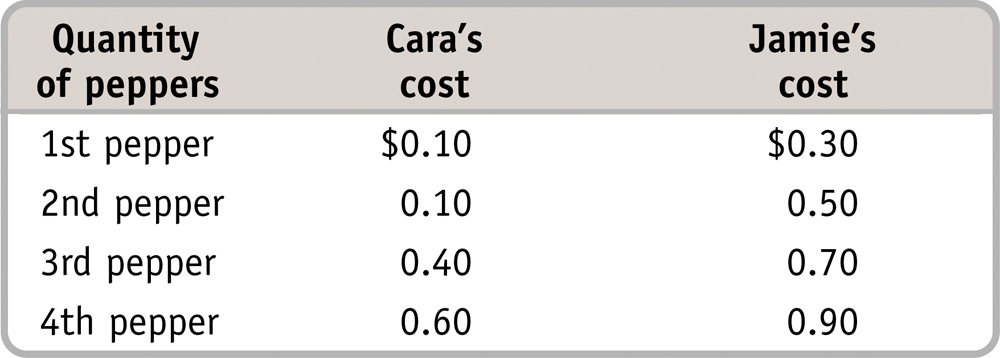

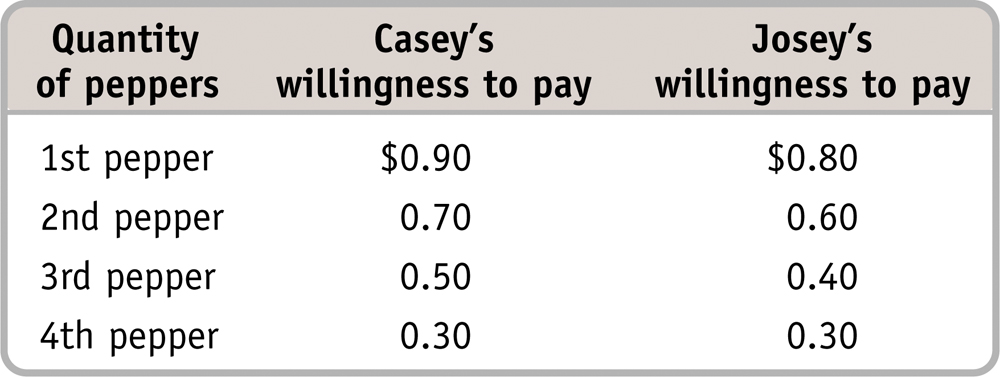

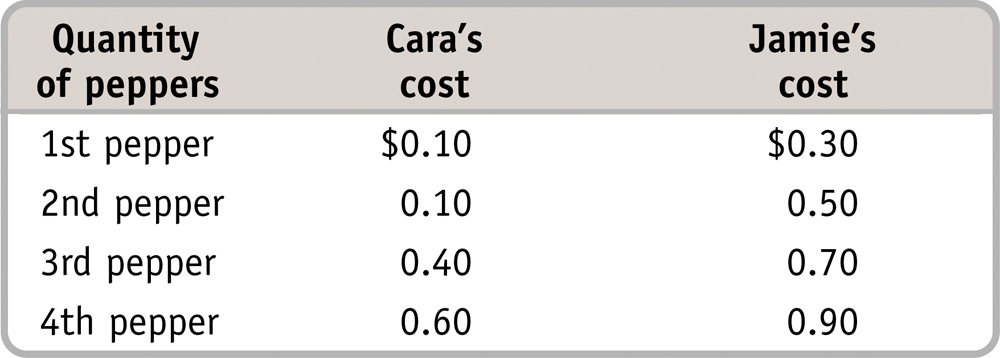

Two consumers, Casey and Josey, want cheese-stuffed jalapeno peppers for lunch. Two producers, Cara and Jamie, can provide them. The accompanying table shows the consumers' willingness to pay and the producers' costs. Note that consumers and producers in this market are not willing to consumer or produce more than four peppers at any price. What is the supply schedule when P = $.70

A. B. C. D. The supply schedule is constructed by asking how many peppers will be supplied at any price.Question

Two consumers, Casey and Josey, want cheese-stuffed jalapeno peppers for lunch. Two producers, Cara and Jamie, can provide them. The accompanying table shows the consumers' willingness to pay and the producers' costs. Note that consumers and producers in this market are not willing to consumer or produce more than four peppers at any price. The demanded quantity when price equals $0.90 is:

A. B. C. A consumer buys each pepper if the price is less than (or just equal to) the consumer"s willingness to pay forthat pepper. The demand schedule is constructed by asking how many peppers will be demanded at any given price. A producer will continue to supply peppers as long as the price is greater than, or just equal to, the producer"s cost.At price of $0.90 only Casey will buy. Josey"s WTP is 0.80 so she will not buy at $0.90

Question

Two consumers, Casey and Josey, want cheese-stuffed jalapeno peppers for lunch. Two producers, Cara and Jamie, can provide them. The accompanying table shows the consumers' willingness to pay and the producers' costs. Note that consumers and producers in this market are not willing to consumer or produce more than four peppers at any price. The equilibrium price and quantity are?

A. B. C. D. The quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied at a price of $0.50, the equilibrium price. At that price, a total quantity of five peppers will be bought and sold.Question

Two consumers, Casey and Josey, want cheese-stuffed jalapeno peppers for lunch. Two producers, Cara and Jamie, can provide them. The accompanying table shows the consumers' willingness to pay and the producers' costs. Note that consumers and producers in this market are not willing to consumer or produce more than four peppers at any price. Total surplus (consumer surplus plus producer surplus) at equilibrium is:

A. B. C. D. Total surplus in this market is therefore $1.00 + $1.10 = $2.10.Question

Two consumers, Casey and Josey, want cheese-stuffed jalapeno peppers for lunch. Two producers, Cara and Jamie, can provide them. The accompanying table shows the consumers' willingness to pay and the producers' costs. Note that consumers and producers in this market are not willing to consumer or produce more than four peppers at any price. Producer surplus at equilibrium is:

A. B. C. D. Cara will supply three peppers and receive a producer surplus of $0.40 on her first, $0.40 on her second, and $0.10 on her third pepper. Jamie will supply two peppers and receive a producer surplus of $0.20 on his first and $0.00 on his second pepper. Total producer surplus is $1.10.Question

Two consumers, Casey and Josey, want cheese-stuffed jalapeno peppers for lunch. Two producers, Cara and Jamie, can provide them. The accompanying table shows the consumers' willingness to pay and the producers' costs. Note that consumers and producers in this market are not willing to consumer or produce more than four peppers at any price. Total consumer surplus at equilibrium is:

A. B. C. D. Casey will buy three peppers and receive a consumer surplus of $0.40 on his first, $0.20 on his second, and $0.00 on his third pepper. Josey will buy two peppers and receive a consumer surplus of $0.30 on her first and $0.10 on her second pepper. Total consumer surplus is therefore $1.00.

Solutions appear at back of book.