Price Floors

The minimum wage is a legal floor on the wage rate, which is the market price of labor.

Sometimes governments intervene to push market prices up instead of down. Price floors have been widely legislated for agricultural products, such as wheat and milk, as a way to support the incomes of farmers. Historically, there were also price floors on such services as trucking and air travel, although these were phased out by the U.S. government in the 1970s. If you have ever worked in a fast-food restaurant, you are likely to have encountered a price floor: governments in the United States and many other countries maintain a lower limit on the hourly wage rate of a worker’s labor; that is, a floor on the price of labor—called the minimum wage.

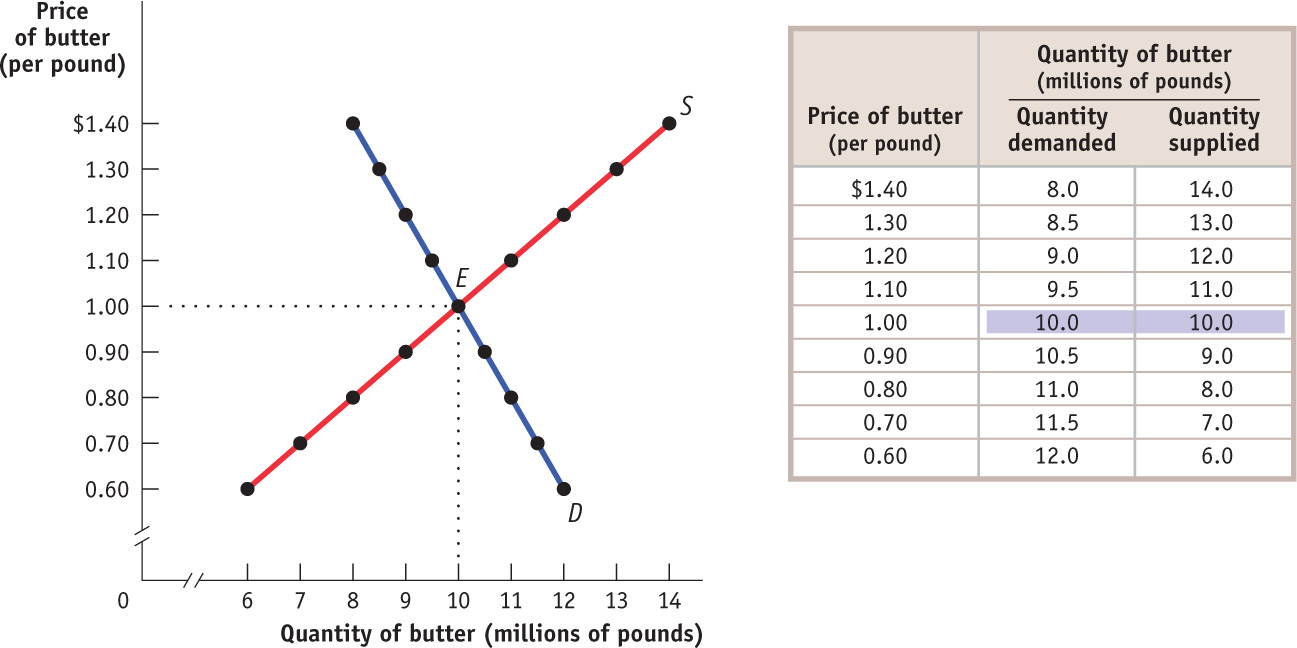

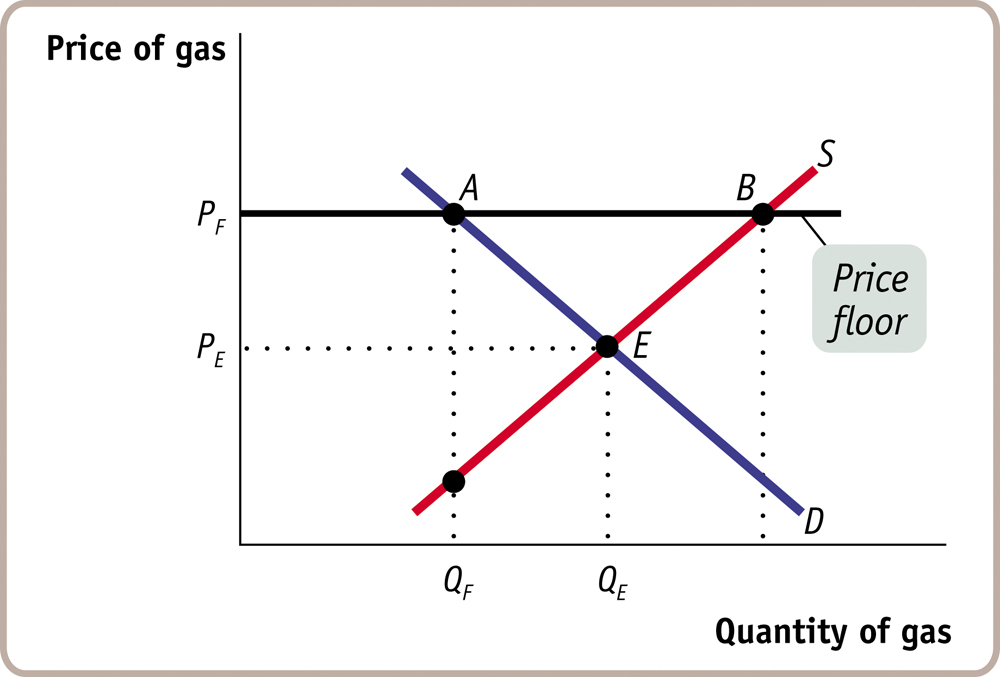

Just like price ceilings, price floors are intended to help some people but generate predictable and undesirable side effects. Figure 4-10 shows hypothetical supply and demand curves for butter. Left to itself, the market would move to equilibrium at point E, with 10 million pounds of butter bought and sold at a price of $1 per pound.

FIGURE 4-10 The Market for Butter in the Absence of Government Controls

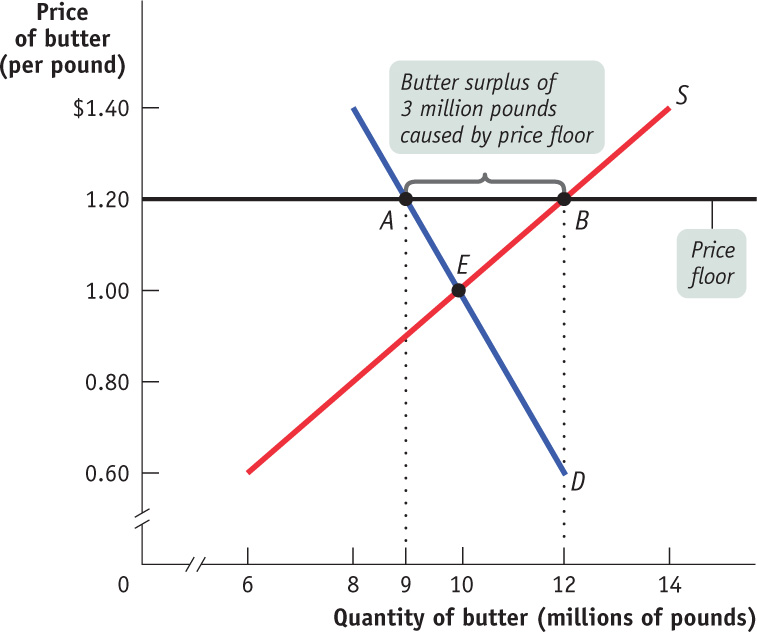

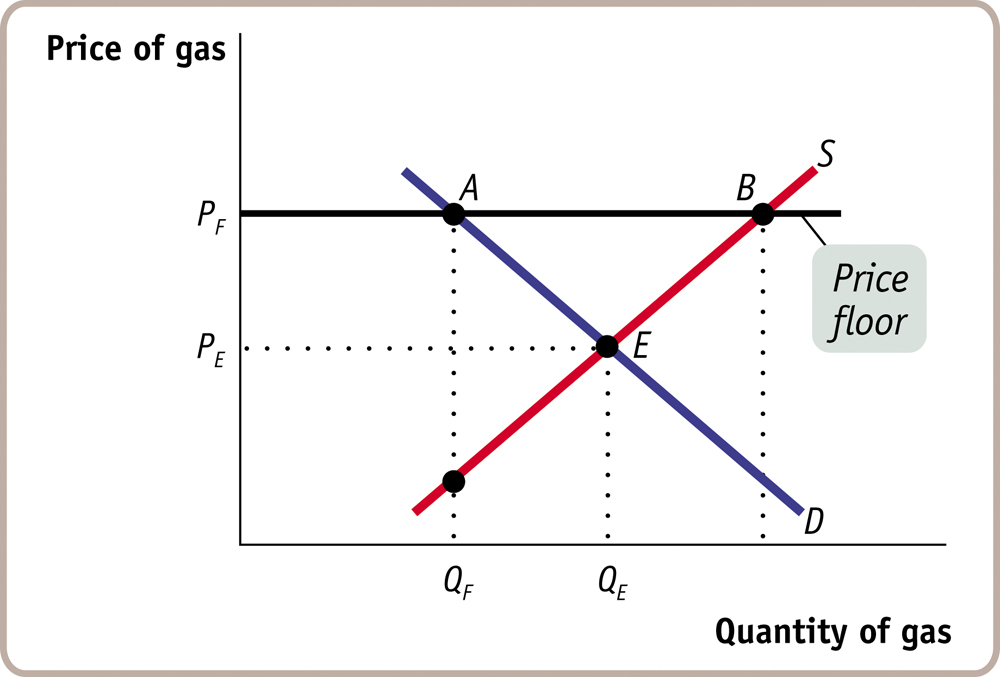

Now suppose that the government, in order to help dairy farmers, imposes a price floor on butter of $1.20 per pound. Its effects are shown in Figure 4-11, where the line at $1.20 represents the price floor. At a price of $1.20 per pound, producers would want to supply 12 million pounds (point B on the supply curve) but consumers would want to buy only 9 million pounds (point A on the demand curve). So the price floor leads to a persistent surplus of 3 million pounds of butter.

FIGURE 4-11 The Effects of a Price Floor

Does a price floor always lead to an unwanted surplus? No. Just as in the case of a price ceiling, the floor may not be binding—that is, it may be irrelevant. If the equilibrium price of butter is $1 per pound but the floor is set at only $0.80, the floor has no effect.

But suppose that a price floor is binding: what happens to the unwanted surplus? The answer depends on government policy. In the case of agricultural price floors, governments buy up unwanted surplus. As a result, the U.S. government has at times found itself warehousing thousands of tons of butter, cheese, and other farm products. (The European Commission, which administers price floors for a number of European countries, once found itself the owner of a so-called butter mountain, equal in weight to the entire population of Austria.) The government then has to find a way to dispose of these unwanted goods.

Some countries pay exporters to sell products at a loss overseas; this is standard procedure for the European Union. The United States gives surplus food away to schools, which use the products in school lunches. In some cases, governments have actually destroyed the surplus production. To avoid the problem of dealing with the unwanted surplus, the U.S. government typically pays farmers not to produce the products at all.

When the government is not prepared to purchase the unwanted surplus, a price floor means that would-be sellers cannot find buyers. This is what happens when there is a price floor on the wage rate paid for an hour of labor, the minimum wage: when the minimum wage is above the equilibrium wage rate, some people who are willing to work—that is, sell labor—cannot find buyers—that is, employers—willing to give them jobs.

How a Price Floor Causes Inefficiency

The persistent surplus that results from a price floor creates missed opportunities—inefficiencies—that resemble those created by the shortage that results from a price ceiling. These include deadweight loss from inefficiently low quantity, inefficient allocation of sales among sellers, wasted resources, inefficiently high quality, and the temptation to break the law by selling below the legal price.

Ceilings, Floors, and Quantities

A price ceiling pushes the price of a good down. A price floor pushes the price of a good up. So it’s easy to assume that the effects of a price floor are the opposite of the effects of a price ceiling. In particular, if a price ceiling reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold, doesn’t a price floor increase the quantity?

No, it doesn’t. In fact, both floors and ceilings reduce the quantity bought and sold. Why? When the quantity of a good supplied isn’t equal to the quantity demanded, the actual quantity sold is determined by the “short side” of the market—whichever quantity is less. If sellers don’t want to sell as much as buyers want to buy, it’s the sellers who determine the actual quantity sold, because buyers can’t force unwilling sellers to sell. If buyers don’t want to buy as much as sellers want to sell, it’s the buyers who determine the actual quantity sold, because sellers can’t force unwilling buyers to buy.

Inefficiently Low Quantity Because a price floor raises the price of a good to consumers, it reduces the quantity of that good demanded; because sellers can’t sell more units of a good than buyers are willing to buy, a price floor reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold below the market equilibrium quantity and leads to a deadweight loss. Notice that this is the same effect as a price ceiling. You might be tempted to think that a price floor and a price ceiling have opposite effects, but both have the effect of reducing the quantity of a good bought and sold (see Pitfalls above).

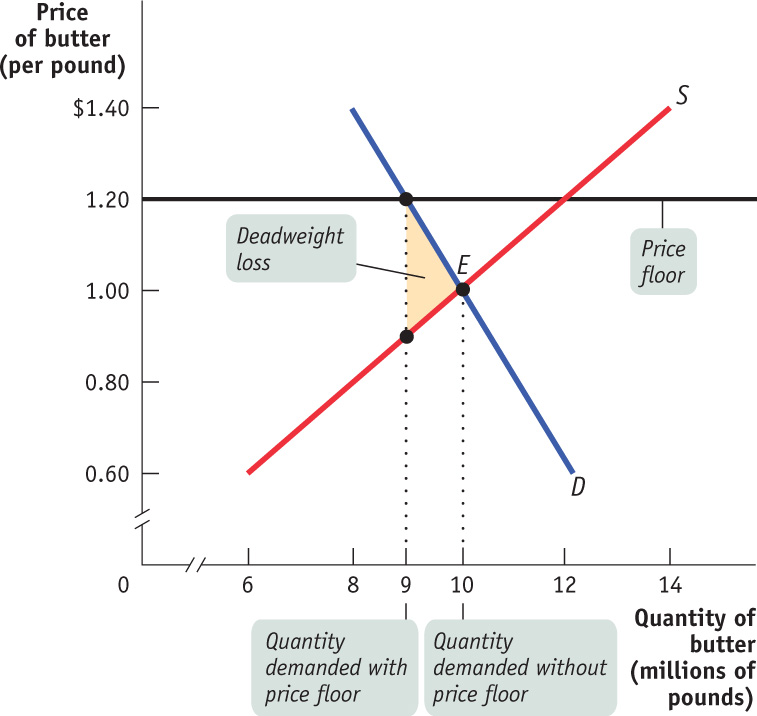

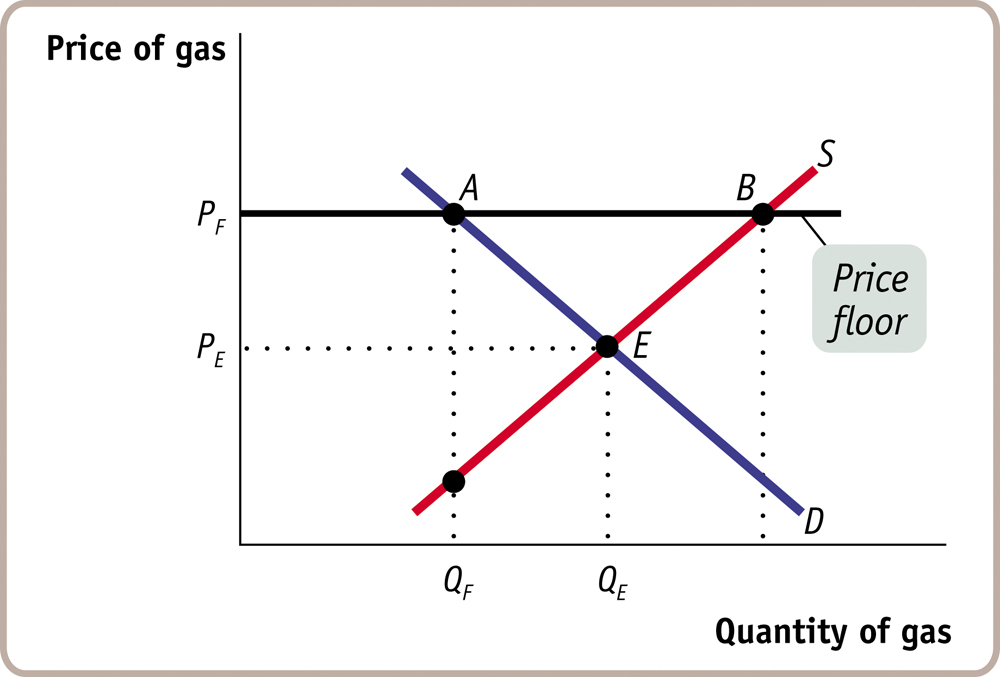

Since the equilibrium of an efficient market maximizes the sum of consumer and producer surplus, a price floor that reduces the quantity below the equilibrium quantity reduces total surplus. Figure 4-12 shows the implications for total surplus of a price floor on the price of butter. Total surplus is the sum of the area above the supply curve and below the demand curve. By reducing the quantity of butter sold, a price floor causes a deadweight loss equal to the area of the shaded triangle in the figure. As in the case of a price ceiling, however, deadweight loss is only one of the forms of inefficiency that the price control creates.

FIGURE 4-12 A Price Floor Causes Inefficiently Low Quantity

Price floors lead to inefficient allocation of sales among sellers: those who would be willing to sell the good at the lowest price are not always those who actually manage to sell it.

Inefficient Allocation of Sales Among Sellers Like a price ceiling, a price floor can lead to inefficient allocation—but in this case inefficient allocation of sales among sellers rather than inefficient allocation to consumers.

An episode from the Belgian movie Rosetta, a realistic fictional story, illustrates the problem of inefficient allocation of selling opportunities quite well. Like many European countries, Belgium has a high minimum wage, and jobs for young people are scarce. At one point Rosetta, a young woman who is very anxious to work, loses her job at a fast-food stand because the owner of the stand replaces her with his son—a very reluctant worker. Rosetta would be willing to work for less money, and with the money he would save, the owner could give his son an allowance and let him do something else. But to hire Rosetta for less than the minimum wage would be illegal.

Wasted Resources Also like a price ceiling, a price floor generates inefficiency by wasting resources. The most graphic examples involve government purchases of the unwanted surpluses of agricultural products caused by price floors. The surplus production is sometimes destroyed, which is pure waste; in other cases, the stored produce goes, as officials euphemistically put it, “out of condition” and must be thrown away.

Price floors also lead to wasted time and effort. Consider the minimum wage. Would-be workers who spend many hours searching for jobs, or waiting in line in the hope of getting jobs, play the same role in the case of price floors as hapless families searching for apartments in the case of price ceilings.

Inefficiently High Quality Again like price ceilings, price floors lead to inefficiency in the quality of goods produced.

Price floors often lead to inefficiency in that goods of inefficiently high quality are offered: sellers offer high-quality goods at a high price, even though buyers would prefer a lower quality at a lower price.

We saw that when there is a price ceiling, suppliers produce products that are of inefficiently low quality: buyers prefer higher-quality products and are willing to pay for them, but sellers refuse to improve the quality of their products because the price ceiling prevents their being compensated for doing so. This same logic applies to price floors, but in reverse: suppliers offer goods of inefficiently high quality.

How can this be? Isn’t high quality a good thing? Yes, but only if it is worth the cost. Suppose that suppliers spend a lot to make goods of very high quality but that this quality isn’t worth much to consumers, who would rather receive the money spent on that quality in the form of a lower price. This represents a missed opportunity: suppliers and buyers could make a mutually beneficial deal in which buyers got goods of lower quality for a much lower price.

A good example of the inefficiency of excessive quality comes from the days when transatlantic airfares were set artificially high by international treaty. Forbidden to compete for customers by offering lower ticket prices, airlines instead offered expensive services, like lavish in-flight meals that went largely uneaten. At one point the regulators tried to restrict this practice by defining maximum service standards—for example, that snack service should consist of no more than a sandwich. One airline then introduced what it called a “Scandinavian Sandwich,” a towering affair that forced the convening of another conference to define sandwich. All of this was wasteful, especially considering that what passengers really wanted was less food and lower airfares.

Since the deregulation of U.S. airlines in the 1970s, American passengers have experienced a large decrease in ticket prices accompanied by a decrease in the quality of in-flight service—smaller seats, lower-quality food, and so on. Everyone complains about the service—but thanks to lower fares, the number of people flying on U.S. carriers has grown several hundred percent since airline deregulation.

Illegal Activity Finally, like price ceilings, price floors provide incentives for illegal activity. For example, in countries where the minimum wage is far above the equilibrium wage rate, workers desperate for jobs sometimes agree to work off the books for employers who conceal their employment from the government—or bribe the government inspectors. This practice, known in Europe as “black labor,” is especially common in Southern European countries such as Italy and Spain (see the upcoming Economics in Action).

Check Out Our Low, Low Wages!

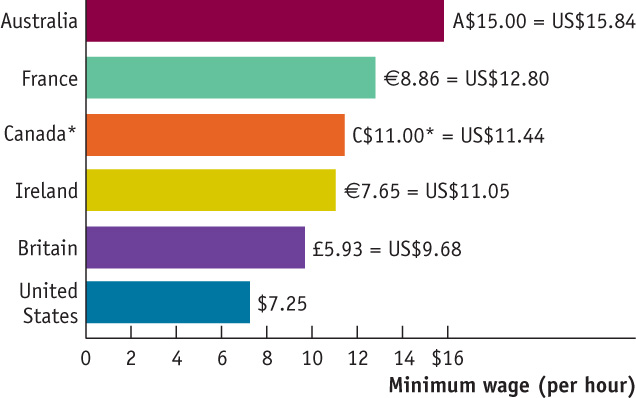

The minimum wage rate in the United States, as you can see in this graph, is actually quite low compared with that in other rich countries. Since minimum wages are set in national currency—the British minimum wage is set in British pounds, the French minimum wage is set in euros, and so on—the comparison depends on the exchange rate on any given day. As of April 15, 2011, Australia had a minimum wage over twice as high as the U.S. rate, with France, Canada, and Ireland not far behind. You can see one effect of this difference in the supermarket checkout line. In the United States there is usually someone to bag your groceries—someone typically paid the minimum wage or at best slightly more. In Europe, where hiring a bagger is a lot more expensive, you’re almost always expected to do the bagging yourself.

*The Canadian minimum wage varies by province from C$8.00 to C$11.00.

So Why are There Price Floors?

To sum up, a price floor creates various negative side effects:

- A persistent surplus of the good

- Inefficiency arising from the persistent surplus in the form of inefficiently low quantity (deadweight loss), inefficient allocation of sales among sellers, wasted resources, and an inefficiently high level of quality offered by suppliers

- The temptation to engage in illegal activity, particularly bribery and corruption of government officials

So why do governments impose price floors when they have so many negative side effects? The reasons are similar to those for imposing price ceilings. Government officials often disregard warnings about the consequences of price floors either because they believe that the relevant market is poorly described by the supply and demand model or, more often, because they do not understand the model. Above all, just as price ceilings are often imposed because they benefit some influential buyers of a good, price floors are often imposed because they benefit some influential sellers.

“Black Labor” In Southern Europe

The best-known example of a price floor is the minimum wage. Most economists believe, however, that the minimum wage has relatively little effect on the job market in the United States, mainly because the floor is set so low. In 1964, the U.S. minimum wage was 53% of the average wage of blue-collar production workers; by 2012, despite several recent increases, it had fallen to about 37%.

The situation is different, however, in many European countries, where minimum wages have been set much higher than in the United States. This has happened despite the fact that workers in most European countries are somewhat less productive than their American counterparts, which means that the equilibrium wage in Europe—the wage that would clear the labor market—is probably lower in Europe than in the United States. Moreover, European countries often require employers to pay for health and retirement benefits, which are more extensive and so more costly than comparable American benefits. These mandated benefits make the actual cost of employing a European worker considerably more than the worker’s paycheck.

The result is that in Europe the price floor on labor is definitely binding: the minimum wage is well above the wage rate that would make the quantity of labor supplied by workers equal to the quantity of labor demanded by employers.

The persistent surplus that results from this price floor appears in the form of high unemployment—millions of workers, especially young workers, seek jobs but cannot find them.

In countries where the enforcement of labor laws is lax, however, there is a second, entirely predictable result: widespread evasion of the law. In both Italy and Spain, officials believe there are hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of workers who are employed by companies that pay them less than the legal minimum, fail to provide the required health and retirement benefits, or both. In many cases the jobs are simply unreported: Spanish economists estimate that about a third of the country’s reported unemployed are in the black labor market—working at unreported jobs. In fact, Spaniards waiting to collect checks from the unemployment office have been known to complain about the long lines that keep them from getting back to work!

Employers in these countries have also found legal ways to evade the wage floor. For example, Italy’s labor regulations apply only to companies with 15 or more workers. This gives a big cost advantage to small Italian firms, many of which remain small in order to avoid paying higher wages and benefits. And sure enough, in some Italian industries there is an astonishing proliferation of tiny companies. For example, one of Italy’s most successful industries is the manufacture of fine woolen cloth, centered in the Prato region. The average textile firm in that region employs only four workers!

Quick Review

- The most familiar price floor is the minimum wage. Price floors are also commonly imposed on agricultural goods.

- A price floor above the equilibrium price benefits successful sellers but causes predictable adverse effects such as a persistent surplus, which leads to four kinds of inefficiencies: deadweight loss from inefficiently low quantity, inefficient allocation of sales among sellers, wasted resources, and inefficiently high quality.

- Price floors encourage illegal activity, such as workers who work off the books, often leading to official corruption.

Check Your Understanding 4-3

Question

The state legislature mandates a price floor for gasoline of PF per gallon as shown in the figure. True or False? The law will increase the income of all gas station owners.

A. B. Some gas station owners will benefit from getting a higher price. QF indicates the sales made by these owners. But some will lose; there are those who make sales at the market equilibrium price of PE but do not make sales at the regulated price of PF. These missed sales are indicated on the graph by the fall in the quantity demanded along the demand curve, from point E to point A.Question

The state legislature mandates a price floor for gasoline of PF per gallon as shown in the figure. True or False? All consumers will be better off because gas stations will provide better service.

A. B. Those who buy gas at the higher price of PF will probably receive better service; this is an example of inefficiently high quality caused by a price floor as gas station owners compete on quality rather than price. But consumers are generally worse off—those who buy at PF would have been happy to buy at PE, and many who were willing to buy at a price between PE and PF are now unwilling to buy. This is indicated on the graph by the fall in the quantity demanded along the demand curve, from point E to point A.Question

The state legislature mandates a price floor for gasoline of PF per gallon as shown in the figure. Proponents claim that they are helping gas station owners without hurting anyone else. Are they correct or incorrect?

A. B. Proponents are wrong because consumers and some gas station owners are hurt by the price floor, which creates “missed opportunities”—desirable transactions between consumers and station owners that never take place. The price floor also tempts people to engage in black market activity.

Solutions appear at back of book.