Business Cases

Kiva Systems’ Robots Versus Humans: The Challenge of Holiday Order Fulfillment

For those who like to procrastinate when it comes to holiday shopping, the rise of e-commerce has been a welcome phenomenon. Amazon.com boasts that in 2012, customers living in 11 cities in the United States could receive same-day delivery for orders placed on the day before Christmas.

E-commerce retailers like Amazon.com and CrateandBarrel.com can see their sales quadruple for the holidays. With advances in order fulfillment technology that get customers’ orders to them quickly, e-commerce sellers have been able to capture an ever-greater share of sales from brick-and-mortar retailers. Holiday sales at e-commerce sites grew by over 13% from 2011 to 2012.

Behind these technological advances, however, lies an intense debate: people versus robots. Amazon has relied on a large staff of temporary human workers to get it through the previous holiday seasons, often quadrupling its staff and operating 24 hours a day. In contrast, Crate and Barrel only doubled its workforce, thanks to a cadre of orange robots that allows each worker to do the work of six people.

But, Amazon is set to increase its robotic work force in the future. In May of 2012, Amazon bought Kiva Systems, the leader in order fulfillment robotics, for $775 million, with the hope of tailoring Kiva’s systems to best fit Amazon’s warehouse and fulfillment needs.

Although many retailers—Staples, Gap, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Walgreens, for example—also use Kiva equipment, installation of a robotic system can be expensive, with some installations costing as much as $20 million. Yet hiring workers has a cost, too: during the 2010 holiday season, before it had installed an extensive robotic system, Amazon hired some 12,500 temporary workers at its 20 distribution centers around the United States.

As one industry analyst noted, an obstacle to the purchase of a robotic system for many e-commerce retailers is that it often doesn’t make economic sense: it’s too expensive to buy sufficient robots for the busiest time of the year because they would be idle at other times. Before Amazon’s purchase, Kiva was testing a program to rent out its robots seasonally so that retailers could “hire” enough robots to handle their holiday orders just like Amazon used to hire more humans.

- Assume that a firm can sell a robot, but that the sale takes time and the firm is likely to get less than what it paid. Other things equal, which system, human-based or robotic, will have a higher fixed cost? Which will have a higher variable cost? Explain.

- Predict the pattern of off-holiday sales versus holiday sales that would induce a retailer to keep a human-based system. Predict the pattern that would induce a retailer to move to a robotic system.

- How would a “robot-for-hire” program affect your answer to Question 2? Explain.

The Find Finds the Cheapest Price

Recently in Sunnyvale, California, Tri Trang walked into a Best Buy and found the perfect gift for his girlfriend: a $184.85 Garmin GPS system. A year earlier, he would have put the item in his cart and purchased it. Instead, he whipped out his Android phone; using an app that instantly compared Best Buy’s price to those of other retailers, he found the same item on for $106.75, with no shipping charges and no sales tax. Trang proceeded to buy it from Amazon, right there on the spot.

It doesn’t stop there. TheFind, the most popular of the price-comparison sites, will also provide a map to the store with the best price, identify coupon codes and shipping deals, and supply other tools to help users organize their purchases. Terror has been the word used to describe the reaction of brick-and-mortar retailers.

Before the advent of apps like TheFind’s, a retailer could lure customers into its store with enticing specials, and reasonably expect them to buy other, more profitable things, too—with some prompting from salespeople. But those days are disappearing. A recent study by the consulting firm Accenture found that 73% of customers with mobile devices prefer to shop by phone rather than talk to a salesperson. Best Buy recently settled a lawsuit alleging that it posted web prices at in-store kiosks faster than the ones customers saw on their home computers, a maneuver that would have been quickly discovered by users of TheFind’s app.

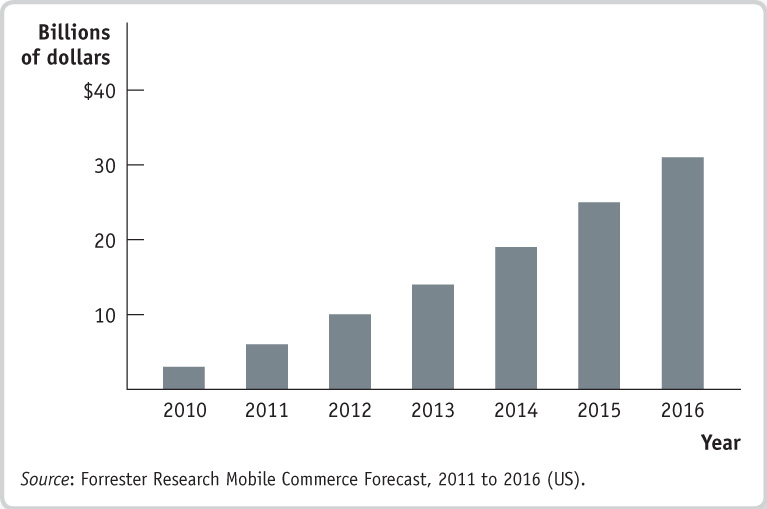

Not surprisingly, use of TheFind’s app has increased at an extremely fast clip. The number of people making purchases on their mobile phone nearly doubled between 2011 and 2012. Indeed, retailers are expecting even more shoppers to use their phones to make purchases in the coming years. The accompanying figure illustrates their projections for dramatic growth in cell phone sales through 2016. On TheFind, the most frequently searched items in stores are iPhones, iPads, video games, and other electronics.

According to e-commerce experts, U.S. retailers have begun to alter their selling strategies in response. One strategy involves stocking products that manufacturers have slightly modified for the retailer, which allows the retailer to be their exclusive seller. In addition, some retailers, when confronted by an in-store customer wielding a lower price on a mobile device, will lower their price to avoid losing the sale.

Yet retailers are clearly frightened. As one analyst said, “Only a couple of retailers can play the lowest-price game. This is going to accelerate the demise of retailers who do not have either competitive pricing or stand-out store experience.”

Expected Growth in Cell Phone Purchases in the United States, 2010–2016

- From the evidence in the case, what can you infer about whether or not the retail market for electronics satisfied the conditions for perfect competition before the advent of mobile-device comparison shopping? What was the most important impediment to competition?

- What effect will the introduction of TheFind’s and similar apps have on competition in the retail market for electronics? On the profitability of brick-and-mortar retailers like Best Buy? What, on average, will be the effect on the consumer surplus of purchasers of these items?

- Why are some retailers responding by having manufacturers make exclusive versions of products for them? Is this trend likely to increase or diminish?