The Economics of Pollution

Pollution is a bad thing. Yet most pollution is a side effect of activities that provide us with good things: our air is polluted by power plants generating the electricity that lights our cities, and our rivers are damaged by fertilizer runoff from farms that grow our food. Why shouldn’t we accept a certain amount of pollution as the cost of a good life?

Actually, we do. Even highly committed environmentalists don’t think that we can or should completely eliminate pollution—even an environmentally conscious society would accept some pollution as the cost of producing useful goods and services. What environmentalists argue is that unless there is a strong and effective environmental policy, our society will generate too much pollution—too much of a bad thing. And the great majority of economists agree.

To see why, we need a framework that lets us think about how much pollution a society should have. We’ll then be able to see why a market economy, left to itself, will produce more pollution than it should. We’ll start by adopting the simplest framework to study the problem—assuming that the amount of pollution emitted by a polluter is directly observable and controllable.

Costs and Benefits of Pollution

How much pollution should society allow? We learned in Chapter 7 that “how much” decisions always involve comparing the marginal benefit from an additional unit of something with the marginal cost of that additional unit. The same is true of pollution.

The marginal social cost of pollution is the additional cost imposed on society as a whole by an additional unit of pollution.

The marginal social cost of pollution is the additional cost imposed on society as a whole by an additional unit of pollution. For example, acid rain damages fisheries, crops, and forests, and each additional ton of sulfur dioxide released into the atmosphere increases the damage.

So How Do You Measure the Marginal Social Cost of Pollution?

It might be confusing to think of marginal social cost—after all, we have up to this point always defined marginal cost as being incurred by an individual or a firm, not society as a whole. But it is easily understandable once we link it to the familiar concept of willingness to pay: the marginal social cost of a unit of pollution is equal to the sum of the willingness to pay among all members of society to avoid that unit of pollution. It’s the sum because, in general, more than one person is affected by the pollution.

But calculating the true cost to society of pollution—marginal or average—is a difficult matter, requiring a great deal of scientific knowledge, as the upcoming Economics in Action on smoking illustrates. As a result, society often underestimates the true marginal social cost of pollution.

The marginal social benefit of pollution is the additional gain to society as a whole from an additional unit of pollution.

The marginal social benefit of pollution—the additional benefit to society from an additional unit of pollution—may seem like a confusing concept. What’s good about pollution? However, avoiding pollution requires using scarce resources that could have been used to produce other goods and services. For example, to reduce the quantity of sulfur dioxide they emit, power companies must either buy expensive low-sulfur coal or install special scrubbers to remove sulfur from their emissions. The more sulfur dioxide they are allowed to emit, the lower these extra costs. Suppose we could calculate how much money the power industry would save if it were allowed to emit an additional ton of sulfur dioxide. That savings would be the marginal benefit to society of emitting an extra ton of sulfur dioxide.

The socially optimal quantity of pollution is the quantity of pollution that society would choose if all the costs and benefits of pollution were fully accounted for.

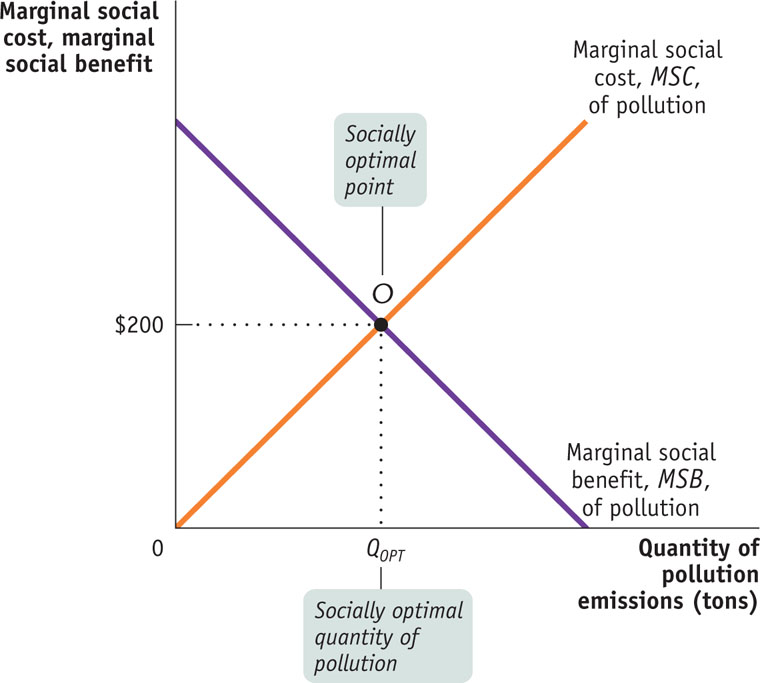

Using hypothetical numbers, Figure 9-1 shows how we can determine the socially optimal quantity of pollution—the quantity of pollution society would choose if all its costs and benefits were fully accounted for. The upward-sloping marginal social cost curve, MSC, shows how the marginal cost to society of an additional ton of pollution emissions varies with the quantity of emissions. (An upward slope is likely because nature can often safely handle low levels of pollution but is increasingly harmed as pollution reaches high levels.) The marginal social benefit curve, MSB, is downward sloping because it is progressively harder, and therefore more expensive, to achieve a further reduction in pollution as the total amount of pollution falls—increasingly more expensive technology must be used. As a result, as total pollution falls, the cost savings to a polluter of being allowed to emit one more ton rises.

FIGURE 9-1 The Socially Optimal Quantity of Pollution

The socially optimal quantity of pollution in this example isn’t zero. It’s QOPT, the quantity corresponding to point O, where MSB crosses MSC. At QOPT, the marginal social benefit from an additional ton of emissions and its marginal social cost are equalized at $200.

But will a market economy, left to itself, arrive at the socially optimal quantity of pollution? No, it won’t.

So How Do You Measure the Marginal Social Benefit of Pollution?

Similar to the problem of measuring the marginal social cost of pollution, the concept of willingness to pay helps us understand the marginal social benefit of pollution in contrast to the marginal benefit to an individual or firm. The marginal social benefit of a unit of pollution is simply equal to the highest willingness to pay for the right to emit that unit measured across all polluters. But unlike the marginal social cost of pollution, the value of the marginal social benefit of pollution is a number likely to be known—to polluters, that is.

Pollution: An External Cost

Pollution yields both benefits and costs to society. But in a market economy without government intervention, those who benefit from pollution—like the owners of power companies—decide how much pollution occurs. They have no incentive to take into account the costs of pollution that they impose on others.

To see why, remember the nature of the benefits and costs from pollution. For polluters, the benefits take the form of monetary savings: by emitting an extra ton of sulfur dioxide, any given polluter saves the cost of buying expensive, low-sulfur coal or installing pollution-control equipment. So the benefits of pollution accrue directly to the polluters.

The costs of pollution, though, fall on people who have no say in the decision about how much pollution takes place: for example, people who fish in northeastern lakes do not control the decisions of power plants.

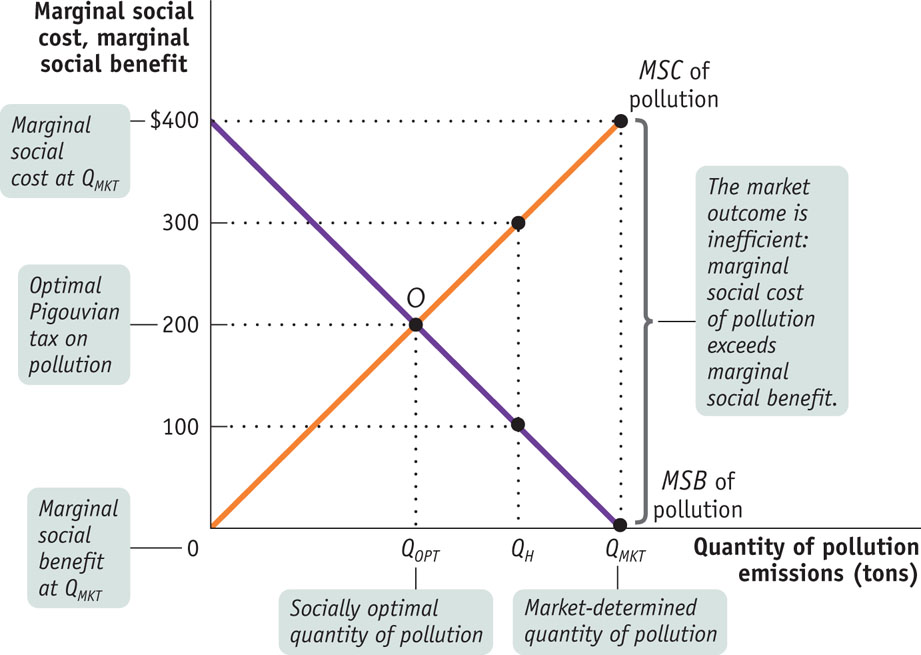

Figure 9-2 shows the result of this asymmetry between who reaps the benefits and who pays the costs. In a market economy without government intervention to protect the environment, only the benefits of pollution are taken into account in choosing the quantity of pollution. So the quantity of emissions won’t be the socially optimal quantity QOPT; it will be QMKT, the quantity at which the marginal social benefit of an additional ton of pollution is zero, but the marginal social cost of that additional ton is much larger—$400. The quantity of pollution in a market economy without government intervention will be higher than its socially optimal quantity. (The Pigouvian tax noted in Figure 9-2 will be explained shortly.)

FIGURE 9-2 Why a Market Economy Produces Too Much Pollution

The reason is that in the absence of government intervention, those who derive the benefits from pollution—in this case, the owners of power plants—don’t have to compensate those who bear the costs. So the marginal cost of pollution to any given polluter is zero: polluters have no incentive to limit the amount of emissions. For example, before the Clean Air Act of 1970, midwestern power plants used the cheapest type of coal available, despite the fact that cheap coal generated more pollution, and they did nothing to scrub their emissions.

An external cost is an uncompensated cost that an individual or firm imposes on others.

An external benefit is a benefit that an individual or firm confers on others without receiving compensation.

External costs and benefits are known as externalities. External costs are negative externalities, and external benefits are positive externalities.

The environmental costs of pollution are the best-known and most important example of an external cost—an uncompensated cost that an individual or firm imposes on others. There are many other examples of external costs besides pollution. Another important, and certainly very familiar, external cost is traffic congestion—an individual who chooses to drive during rush hour increases congestion and so increases the travel time of other drivers.

We’ll see later in this chapter that there are also important examples of external benefits, benefits that individuals or firms confer on others without receiving compensation. External costs and benefits are jointly known as externalities, with external costs called negative externalities and external benefits called positive externalities.

As we’ve already suggested, externalities can lead to individual decisions that are not optimal for society as a whole. Let’s take a closer look at why.

Talking, Texting, and Driving

Why is that woman in the car in front of us driving so erratically? Is she drunk? No, she’s talking on her cell phone or texting.

Traffic safety experts take the risks posed by driving while using a cell phone very seriously: Using data from 2010, the National Safety Council estimated that almost a quarter of all traffic accidents involve distracted drivers who are either talking or texting on their cell phones. This translates to 1.1 million crashes caused by talking on cell phones, and 160,000 crashes that involve texting. Other estimates suggest that talking on cell phones while driving may be responsible for 3,000 or more traffic deaths each year. And using hands-free, voice-activated phones to make a call doesn’t seem to help much because the main danger is distraction. As one traffic consultant put it, “It’s not where your eyes are; it’s where your head is.”

The National Safety Council urges people not to use phones while driving. Most states have some restrictions on talking on a cell phone while driving. But in response to a growing number of accidents, several states have banned cell phone use behind the wheel altogether. In 39 states and the District of Columbia, it is illegal to text and drive. Cell phone use while driving is illegal in many other countries as well, including Japan and Israel.

Why not leave the decision up to the driver? Because the risk posed by driving while using a cell phone isn’t just a risk to the driver; it’s also a safety risk to others—to a driver’s passengers, pedestrians, and people in other cars. Even if you decide that the benefit to you of using your cell phone while driving is worth the cost, you aren’t taking into account the cost to other people. Driving while using a cell phone, in other words, generates a serious—and sometimes fatal—negative externality.

The Inefficiency of Excess Pollution

We have just shown that in the absence of government action, the quantity of pollution will be inefficient: polluters will pollute up to the point at which the marginal social benefit of pollution is zero, as shown by the pollution quantity, QMKT, in Figure 9-2.

Because the marginal social benefit of pollution is zero at QMKT, reducing the quantity of pollution by one ton would subtract very little from the total social benefit from pollution. In other words, the benefit to polluters from that last unit of pollution is very low—virtually zero. Meanwhile, the marginal social cost imposed on the rest of society of that last ton of pollution at QMKT is quite high—$400. In other words, by reducing the quantity of pollution at QMKT by one ton, the total social cost of pollution falls by $400, but total social benefit falls by virtually zero. So total surplus rises by approximately $400 if the quantity of pollution at QMKT is reduced by one ton.

If the quantity of pollution is reduced further, there will be more gains in total surplus, though they will be smaller. For example, if the quantity of pollution is QH in Figure 9-2, the marginal social benefit of a ton of pollution is $100, but the marginal social cost is still $300. In other words, reducing the quantity of pollution by one ton leads to a net gain in total surplus of approximately $300 − $100 = $200. This tells us that QH is still an inefficiently high quantity of pollution. Only if the quantity of pollution is reduced to QOPT, where the marginal social cost and the marginal social benefit of an additional ton of pollution are both $200, is the outcome efficient.

Private Solutions to Externalities

Can the private sector solve the problem of externalities without government intervention? Bear in mind that when an outcome is inefficient, there is potentially a deal that makes people better off. Why don’t individuals find a way to make that deal?

According to the Coase theorem, even in the presence of externalities an economy can always reach an efficient solution as long as transaction costs—the costs to individuals of making a deal—are sufficiently low.

In an influential 1960 article, the economist and Nobel laureate Ronald Coase pointed out that in an ideal world the private sector could indeed deal with all externalities. According to the Coase theorem, even in the presence of externalities an economy can always reach an efficient solution provided that the costs of making a deal are sufficiently low. The costs of making a deal are known as transaction costs.

To get a sense of Coase’s argument, imagine two neighbors, Mick and Christina, who both like to barbecue in their backyards on summer afternoons. Mick likes to play golden oldies on his boombox while barbecuing, but this annoys Christina, who can’t stand that kind of music.

Who prevails? You might think that it depends on the legal rights involved in the case: if the law says that Mick has the right to play whatever music he wants, Christina just has to suffer; if the law says that Mick needs Christina’s consent to play music in his backyard, Mick has to live without his favorite music while barbecuing.

But as Coase pointed out, the outcome need not be determined by legal rights, because Christina and Mick can make a private deal. Even if Mick has the right to play his music, Christina could pay him not to. Even if Mick can’t play the music without an OK from Christina, he can offer to pay her to give that OK. These payments allow them to reach an efficient solution, regardless of who has the legal upper hand. If the benefit of the music to Mick exceeds its cost to Christina, the music will go on; if the benefit to Mick is less than the cost to Christina, there will be silence.

When individuals take external costs or benefits into account, they internalize the externality.

The implication of Coase’s analysis is that externalities need not lead to inefficiency because individuals have an incentive to make mutually beneficial deals—deals that lead them to take externalities into account when making decisions. When individuals do take externalities into account when making decisions, economists say that they internalize the externality. If externalities are fully internalized, the outcome is efficient even without government intervention.

Why can’t individuals always internalize externalities? Our barbecue example implicitly assumes the transaction costs are low enough for Mick and Christina to be able to make a deal. In many situations involving externalities, however, transaction costs prevent individuals from making efficient deals. Examples of transaction costs include the following:

- The costs of communication among the interested parties. Such costs may be very high if many people are involved.

- The costs of making legally binding agreements. Such costs may be high if expensive legal services are required.

- Costly delays involved in bargaining. Even if there is a potentially beneficial deal, both sides may hold out in an effort to extract more favorable terms, leading to increased effort and forgone benefit.

In some cases, people do find ways to reduce transaction costs, allowing them to internalize externalities. For example, a house with a junk-filled yard and peeling paint imposes a negative externality on the neighboring houses, diminishing their value in the eyes of potential house buyers. So many people live in private communities that set rules for home maintenance and behavior, making bargaining between neighbors unnecessary. But in many other cases, transaction costs are too high to make it possible to deal with externalities through private action. For example, tens of millions of people are adversely affected by acid rain. It would be prohibitively expensive to try to make a deal among all those people and all those power companies.

When transaction costs prevent the private sector from dealing with externalities, it is time to look for government solutions. We turn to public policy in the next section.

Thank You for not Smoking

New Yorkers call them the “shiver-and-puff people”—the smokers who stand outside their workplaces, even in the depths of winter, to take a cigarette break. Over the past couple of decades, rules against smoking in spaces shared by others have become ever stricter. This is partly a matter of personal dislike—nonsmokers really don’t like to smell other people’s cigarette smoke—but it also reflects concerns over the health risks of second-hand smoke. As the Surgeon General’s warning on many packs says, “Smoking causes lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and may complicate pregnancy.” And there’s no question that being in the same room as someone who smokes exposes you to at least some health risk.

Second-hand smoke, then, is clearly an example of a negative externality. But how important is it? Putting a dollar-and-cents value on it—that is, measuring the marginal social cost of cigarette smoke—requires not only estimating the health effects but putting a value on these effects. Despite the difficulty, economists have tried. A paper published in 1993 in the Journal of Economic Perspectives surveyed the research on the external costs of both cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption.

According to this paper, valuing the health costs of cigarettes depends on whether you count the costs imposed on members of smokers’ families, including unborn children, in addition to costs borne by smokers. If you don’t, the external costs of second-hand smoke have been estimated at about only $0.19 per pack smoked. (Using this method of calculation, $0.19 corresponds to the average social cost of smoking per pack at the current level of smoking in society.) A 2005 study raised this estimate to $0.52 per pack smoked. If you include effects on smokers’ families, the number rises considerably—family members who live with smokers are exposed to a lot more smoke. (They are also exposed to the risk of fires, which alone is estimated at $0.09 per pack.) If you include the effects of smoking by pregnant women on their unborn children’s future health, the cost is immense—$4.80 per pack, which is more than twice the wholesale price charged by cigarette manufacturers.

Quick Review

- There are costs as well as benefits to reducing pollution, so the optimal quantity of pollution isn’t zero. Instead, the socially optimal quantity of pollution is the quantity at which the marginal social cost of pollution is equal to the marginal social benefit of pollution.

- Left to itself, a market economy will typically generate an inefficiently high level of pollution because polluters have no incentive to take into account the costs they impose on others.

- External costs and benefits are known as externalities. Pollution is an example of an external cost, or negative externality; in contrast, some activities can give rise to external benefits, or positive externalities.

- According to the Coase theorem, the private sector can sometimes resolve externalities on its own: if transaction costs aren’t too high, individuals can reach a deal to internalize the externality. When transaction costs are too high, government intervention may be warranted.

Check Your Understanding 9-1

Question

Wastewater runoff from large poultry farms adversely affects their neighbors. What is the nature of the external cost imposed?

A. B. The external cost is the pollution caused by the wastewater runoff, an uncompensated cost imposed by the poultry farms on their neighbors.Question

Wastewater runoff from large poultry farms adversely affects their neighbors. Which of the following explains the result in the absence of government intervention or a private deal?

A. B. Since poultry farmers do not take the external cost of their actions into account when making decisions about how much wastewater to generate, they will create more runoff than is socially optimal in the absence of government intervention or a private deal. They will produce runoff up to the point at which the marginal social benefit of an additional unit of runoff is zero; however, their neighbors experience a high, positive level of marginal social cost of runoff from this output level. So the quantity of wastewater runoff is inefficient: reducing runoff by one unit would reduce total social benefit by less than it would reduce total social cost.Question

Wastewater runoff from large poultry farms adversely affects their neighbors. What is the socially optimal outcome?

A. B. At the socially optimal quantity of wastewater runoff, the marginal social benefit is equal to the marginal social cost. This quantity is lower than the quantity of wastewater runoff that would be created in the absence of government intervention or a private deal.

Question

According to Yasmin, any student who borrows a book from the university library and fails to return it on time imposes a negative externality on other students. She claims that rather than charging a modest fine for late returns, the library should charge a huge fine, so that borrowers will never return a book late. Is Yasmin’s economic reasoning correct?

A. B. Yasmin’s reasoning is not correct: allowing some late returns of books is likely to be socially optimal. Although you impose a marginal social cost on others every day that you are late in returning a book, there is some positive marginal social benefit to you of returning a book late—for example, you get a longer period to use it in working on a term paper. The socially optimal number of days that a book is returned late is the number at which the marginal social benefit equals the marginal social cost. A fine so stiff that it prevents any late returns is likely to result in a situation in which people return books although the marginal social benefit of keeping them another day is greater than the marginal social cost—an inefficient outcome. In that case, allowing an overdue patron another day would increase total social benefit more than it would increase total social cost. So charging a moderate fine that reduces the number of days that books are returned late to the socially optimal number of days is appropriate.

Solutions appear at back of book.