The Monetary Role of Banks

Roughly 40% of M1, the narrowest definition of the money supply, consists of currency in circulation—

What Banks Do

As we learned in Chapter 10, a bank is a financial intermediary that uses liquid assets in the form of bank deposits to finance the illiquid investments of borrowers. Banks can create liquidity because it isn’t necessary for a bank to keep all of the funds deposited with it in the form of highly liquid assets. Except in the case of a bank run—which we’ll get to shortly—

Bank reserves are the currency banks hold in their vaults plus their deposits at the Federal Reserve.

Banks can’t, however, lend out all the funds placed in their hands by depositors because they have to satisfy any depositor who wants to withdraw his or her funds. In order to meet these demands, a bank must keep substantial quantities of liquid assets on hand. In the modern U.S. banking system, these assets take the form either of currency in the bank’s vault or deposits held in the bank’s own account at the Federal Reserve. As we’ll see shortly, the latter can be converted into currency more or less instantly. Currency in bank vaults and bank deposits held at the Federal Reserve are called bank reserves. Because bank reserves are in bank vaults and at the Federal Reserve, not held by the public, they are not part of currency in circulation.

A T-

To understand the role of banks in determining the money supply, we start by introducing a simple tool for analyzing a bank’s financial position: a T-

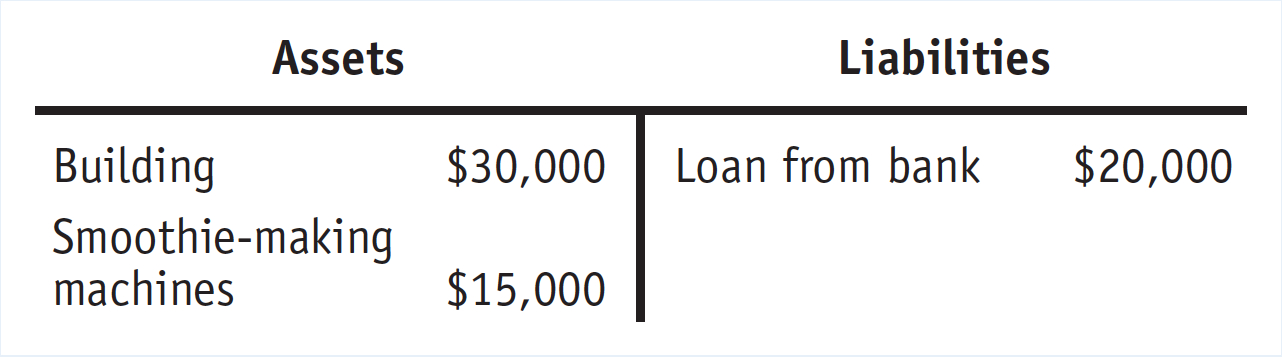

Figure 14-2 shows the T-

14-2

A T-

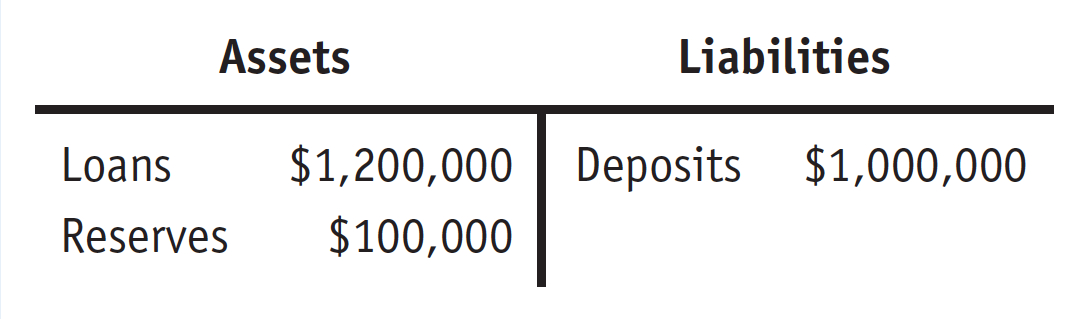

Samantha’s Smoothies is an ordinary, nonbank business. Now let’s look at the T-

Figure 14-3 shows First Street Bank’s financial position. The loans First Street Bank has made are on the left side because they’re assets: they represent funds that those who have borrowed from the bank are expected to repay. The bank’s only other assets, in this simplified example, are its reserves, which, as we’ve learned, can take the form either of cash in the bank’s vault or deposits at the Federal Reserve. On the right side we show the bank’s liabilities, which in this example consist entirely of deposits made by customers at First Street Bank. These are liabilities because they represent funds that must ultimately be repaid to depositors.

14-3

Assets and Liabilities of First Street Bank

Notice, by the way, that in this example First Street Bank’s assets are larger than its liabilities. That’s the way it’s supposed to be! In fact, as we’ll see shortly, banks are required by law to maintain assets larger by a specific percentage than their liabilities.

The reserve ratio is the fraction of bank deposits that a bank holds as reserves.

In this example, First Street Bank holds reserves equal to 10% of its customers’ bank deposits. The fraction of bank deposits that a bank holds as reserves is its reserve ratio. In the modern American system, the Federal Reserve—

The Problem of Bank Runs

A bank can lend out most of the funds deposited in its care because in normal times only a small fraction of its depositors want to withdraw their funds on any given day. But what would happen if, for some reason, all or at least a large fraction of its depositors did try to withdraw their funds during a short period of time, such as a couple of days?

If a significant share of its depositors demanded their money back at the same time, the bank wouldn’t be able to raise enough cash to meet those demands. The reason is that banks convert most of their depositors’ funds into loans made to borrowers; that’s how banks earn revenue—

Bank loans, however, are illiquid: they can’t easily be converted into cash on short notice. To see why, imagine that First Street Bank has lent $100,000 to Drive-

The upshot is that if a significant number of First Street Bank’s depositors suddenly decided to withdraw their funds, the bank’s efforts to raise the necessary cash quickly would force it to sell off its assets very cheaply. Inevitably, this leads to a bank failure: the bank would be unable to pay off its depositors in full.

What might start this whole process? That is, what might lead First Street Bank’s depositors to rush to pull their money out? A plausible answer is a spreading rumor that the bank is in financial trouble. Even if depositors aren’t sure the rumor is true, they are likely to play it safe and get their money out while they still can. And it gets worse: a depositor who simply thinks that other depositors are going to panic and try to get their money out will realize that this could “break the bank.” So he or she joins the rush. In other words, fear about a bank’s financial condition can be a self-

A bank run is a phenomenon in which many of a bank’s depositors try to withdraw their funds due to fears of a bank failure.

A bank run is a phenomenon in which many of a bank’s depositors try to withdraw their funds due to fears of a bank failure. Moreover, bank runs aren’t bad only for the bank in question and its depositors. Historically, they have often proved contagious, with a run on one bank leading to a loss of faith in other banks, causing additional bank runs.

The upcoming Economics in Action describes an actual case of just such a contagion, the wave of bank runs that swept across the United States in the early 1930s. In response to that experience and similar experiences in other countries, the United States and most other modern governments have established a system of bank regulations that protect depositors and prevent most bank runs. We’ll encounter bank runs again in Chapter 17, which contains an in-

Bank Regulation

Should you worry about losing money in the United States due to a bank run? No. After the banking crises of the 1930s, the United States and most other countries put into place a system designed to protect depositors and the economy as a whole against bank runs. This system has four main features: deposit insurance, capital requirements, reserve requirements, and, in addition, banks have access to the discount window, a source of cash when it’s needed.

Deposit insurance guarantees that a bank’s depositors will be paid even if the bank can’t come up with the funds, up to a maximum amount per account.

1. Deposit Insurance Almost all banks in the United States advertise themselves as a “member of the FDIC”—the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. As we learned in Chapter 10, the FDIC provides deposit insurance, a guarantee that depositors will be paid even if the bank can’t come up with the funds, up to a maximum amount per account. The FDIC currently guarantees the first $250,000 per depositor, per insured bank.

It’s important to realize that deposit insurance doesn’t just protect depositors if a bank actually fails. The insurance also eliminates the main reason for bank runs: since depositors know their funds are safe even if a bank fails, they have no incentive to rush to pull them out because of a rumor that the bank is in trouble.

2. Capital Requirements Deposit insurance, although it protects the banking system against bank runs, creates a well-

To reduce the incentive for excessive risk taking, regulators require that the owners of banks hold substantially more assets than the value of bank deposits. That way, the bank will still have assets larger than its deposits even if some of its loans go bad, and losses will accrue against the bank owners’ assets, not the government. The excess of a bank’s assets over its bank deposits and other liabilities is called the bank’s capital. For example, First Street Bank has capital of $300,000, equal to $300,000/($1,200,000 + $100,000) = 23% of the total value of its assets. In practice, banks’ capital is required to equal at least 7% of the value of their assets.

Reserve requirements are rules set by the Federal Reserve that determine the minimum reserve ratio for banks.

3. Reserve Requirements Another regulation used to reduce the risk of bank runs is reserve requirements, rules set by the Federal Reserve that specify the minimum reserve ratio for banks. For example, in the United States, the minimum reserve ratio for checkable bank deposits is 10%.

The discount window is an arrangement in which the Federal Reserve stands ready to lend money to banks in trouble.

4. The Discount Window One final protection against bank runs is the fact that the Federal Reserve, which we’ll discuss more thoroughly later in this chapter, stands ready to lend money to banks in trouble, an arrangement known as the discount window. The ability to borrow money means a bank can avoid being forced to sell its assets at fire-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: It’s a Wonderful Banking System

It’s a Wonderful Banking System

Next Christmastime, it’s a sure thing that at least one TV channel will show the 1946 film It’s a Wonderful Life, featuring Jimmy Stewart as George Bailey, a small-

When the movie was made, such scenes were still fresh in Americans’ memories. There was a wave of bank runs in late 1930, a second wave in the spring of 1931, and a third wave in early 1933. By the end, more than a third of the nation’s banks had failed. To bring the panic to an end, on March 6, 1933, the newly inaugurated president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, declared a national “bank holiday,” closing all banks for a week to give bank regulators time to close unhealthy banks and certify healthy ones.

Since then, regulation has protected the United States and other wealthy countries against most bank runs. In fact, the scene in It’s a Wonderful Life was already out of date when the movie was made. But recent decades have seen several waves of bank runs in developing countries. For example, bank runs played a role in an economic crisis that swept Southeast Asia in 1997–

Notice that we said most bank runs. There are some limits on deposit insurance; in particular, in the United States currently only the first $250,000 of an individual depositor’s funds in an insured bank is covered. As a result, there can still be a run on a bank perceived as troubled. In fact, that’s exactly what happened in July 2008 to IndyMac, a Pasadena-

Quick Review

A T-

account is used to analyze a bank’s financial position. A bank holds bank reserves—currency in its vaults plus deposits held in its account at the Federal Reserve. The reserve ratio is the ratio of bank reserves to customers’ bank deposits.Because bank loans are illiquid, but a bank is obligated to return depositors’ funds on demand, bank runs are a potential problem. Although they took place on a massive scale during the 1930s, they have been largely eliminated in the United States through bank regulation in the form of deposit insurance, capital requirements, and reserve requirements, as well as through the availability of the discount window.

14-2

Question 14.4

Suppose you are a depositor at First Street Bank. You hear a rumor that the bank has suffered serious losses on its loans. Every depositor knows that the rumor isn’t true, but each thinks that most other depositors believe the rumor. Why, in the absence of deposit insurance, could this lead to a bank run? How does deposit insurance change the situation?

Even though you know that the rumor about the bank is not true, you are concerned about other depositors pulling their money out of the bank. And you know that if enough other depositors pull their money out, the bank will fail. In that case, it is rational for you to pull your money out before the bank fails. All depositors will think like this, so even if they all know that the rumor is false, they may still rationally pull their money out, leading to a bank run. Deposit insurance leads depositors to worry less about the possibility of a bank run. Even if a bank fails, the FDIC will currently pay each depositor up to $250,000 per account. This will make you much less likely to pull your money out in response to a rumor. Since other depositors will think the same, there will be no bank run.

Question 14.5

A con artist has a great idea: he’ll open a bank without investing any capital and lend all the deposits at high interest rates to real estate developers. If the real estate market booms, the loans will be repaid and he’ll make high profits. If the real estate market goes bust, the loans won’t be repaid and the bank will fail—

but he will not lose any of his own wealth. How would modern bank regulation frustrate his scheme? The aspects of modern bank regulation that would frustrate this scheme are capital requirements and reserve requirements. Capital requirements mean that a bank has to have a certain amount of capital—the difference between its assets (loans plus reserves) and its liabilities (deposits). So the con artist could not open a bank without putting any of his own wealth in because the bank needs a certain amount of capital—that is, it needs to hold more assets (loans plus reserves) than deposits. So the con artist would be at risk of losing his own wealth if his loans turn out badly.

Solutions appear at back of book.