The 2008 Crisis and Its Aftermath

As we’ve just seen, banking crises have typically been followed by major economic problems. How did the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008 compare with this historical experience? The answer, unfortunately, is that history has proved a very good guide: once again, the economic damage from the financial crisis was both large and prolonged. And aftershocks from the crisis continue to shake the world economy today.

Severe Crisis, Slow Recovery

17-6

Crisis and Recovery in the United States and the Eurozone

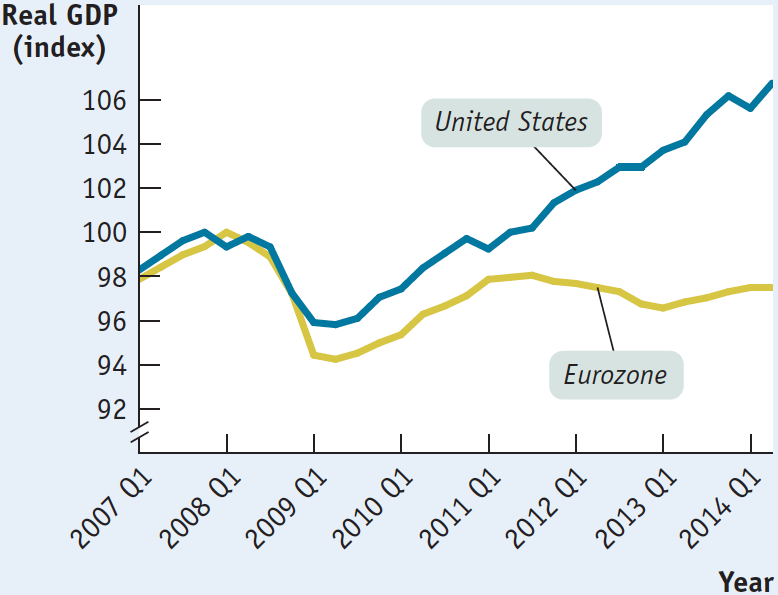

Figure 17-6 shows real GDP during the crisis and aftermath in the United States and the eurozone—the group of countries using the euro as a shared currency, which together form an economy roughly the same size as that of the United States. For both economies real GDP is shown as an index with the peak pre-

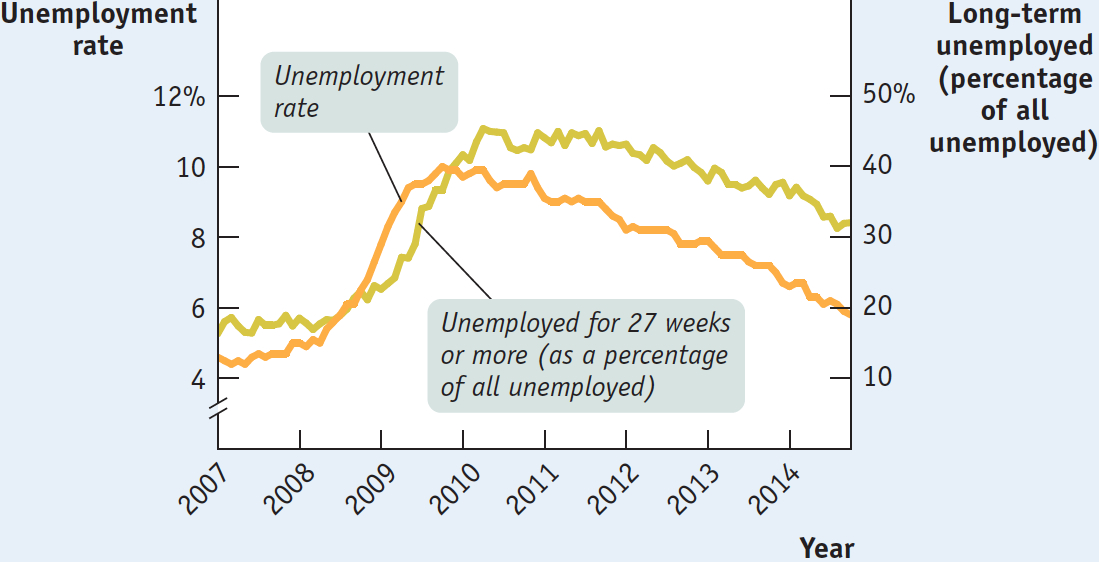

The severe slump and the slow recovery in the United States were very bad news for workers, since a healthy job market depends on an economy growing fast enough to accommodate both a growing workforce and rising productivity. Figure 17-7 shows two indicators of unemployment in the United States—

17-7

U.S. Unemployment in the Aftermath of the 2008 Crisis

This outcome was, sad to say, about what one should have expected given the severity of the initial financial shock and the historical experience with such shocks. Look back at Figure 17-2: compared with either the Panic of 1893 or the aftermath of the Swedish banking crisis of 1991, the U.S. experience after 2008, the Great Recession, has if anything been better. The United States, observed Kenneth Rogoff (whose work we cited earlier), has experienced a “garden variety severe financial crisis.”

Aftershocks in Europe

One important factor bedeviling hopes for recovery was the emergence of special difficulties in several European nations—

The 2008 crisis was caused by problems with private debt, mainly home loans, which then triggered a crisis of confidence in banks. In 2011 and 2012, there were fears of a second crisis, this one arising from concerns about whether Southern European countries as well as Ireland could repay their burgeoning public debts.

Europe’s troubles first surfaced in Greece, a country with a long history of fiscal irresponsibility. In late 2009 it was revealed that the previous Greek government had understated the size of the budget deficits and the amount of government debt. This prompted lenders to refuse further loans to Greece. To prevent a default on Greek public debt, other European countries provided emergency loans to the Greek government in return for harsh cuts to the Greek government budget. But these cuts depressed the Greek economy, and by late 2011 there was general agreement that Greece would be unable to pay back its public debt in full.

By itself, this was a manageable shock for the European economy since Greece accounts for less than 3% of European GDP. Unfortunately, foot-

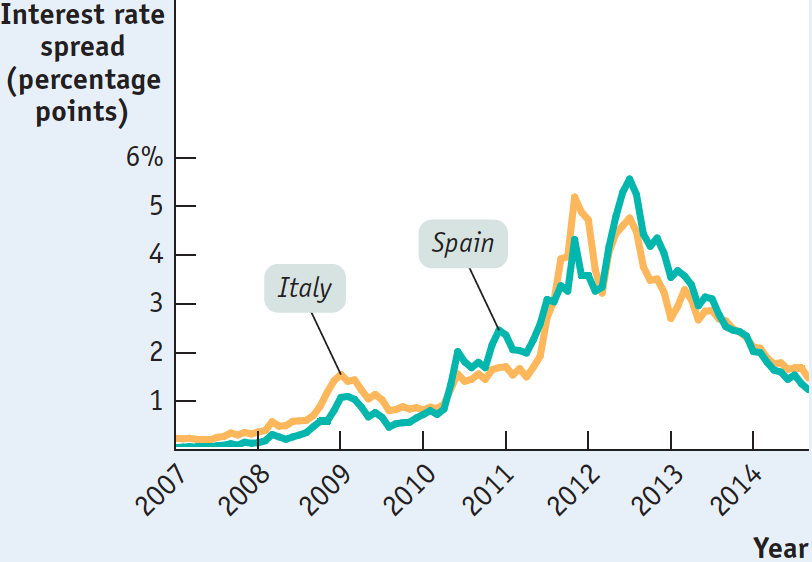

Figure 17-8 shows a measure of pressure on Italy and Spain during the 2008 and 2011 crises: the difference between interest rates on 10-

17-8

Interest Rate Spread Against German 10-

Spain’s fiscal problems were mainly fallout from the 2008 crisis. Before that crisis, Spain seemed to be in very good fiscal condition, with low debt and a budget surplus. However, Spain, like Ireland, had a huge housing bubble between 2000 and 2007. When the bubble burst, the Spanish economy fell into a deep slump, depressing tax receipts and causing large budget deficits. At the same time, there were worries that the Spanish government might eventually have to spend large amounts bailing out banks. As a result, investors began worrying about the solvency of the Spanish government and a possible default.

Italy’s case was somewhat different. Italy has long had high levels of public debt as a percentage of GDP, but it has not run large deficits in recent years; as late as the spring of 2010 its fiscal position looked fairly stable. At that point, however, investors began to have doubts about the Italian government’s solvency, in part because in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis the Italian economy was growing very slowly—

Some economists argued that the problems of Spain and Italy were exacerbated by the fact that, having adopted the euro, their debts were in effect in a foreign currency. Why does this matter? Governments like those of the United States, Britain, or Japan, which borrow in their own currencies, can’t run out of money—

This argument gained a lot of credibility in 2012, when the European Central Bank declared that it would become a lender of last resort for the eurozone by buying directly the bonds of troubled governments in that area if necessary, greatly reducing the fears of a liquidity crisis for these governments. As you can see in Figure 17-8, spreads on Spanish and Italian debt fell sharply after the announcement. Although immediate fears of government defaults in the eurozone had been greatly eased, at the time of writing Europe’s economic difficulties remain grave.

The Stimulus–Austerity Debate

Contractionary fiscal measures such as spending cuts and tax increases aimed at reducing budget deficits are known as fiscal austerity.

The persistence of economic difficulties after the 2008 financial crisis led to fierce debates about appropriate policy responses. Broadly speaking, economists and policy makers were divided as to whether the situation called for more fiscal stimulus—

The proponents of more stimulus pointed to the continuing poor performance of major economies, arguing that the combination of high unemployment and relatively low inflation clearly pointed to the need for expansionary policies. And since monetary policy was limited by the zero bound (a concept we discussed in Chapter 16) for interest rates, stimulus proponents advocated expansionary fiscal policy to fill the gap.

The austerity camp took a very different view. Strongly influenced by the solvency troubles of Greece, they argued that the common source of all the problems were high levels of government deficits and debts. In their view, countries like the United States that continued to run large government deficits several years after the 2008 crisis were at risk of suffering a similar loss of investor confidence in their ability to repay their debts. Moreover, austerity advocates claimed that cuts in government spending would not actually be contractionary because they would improve investor confidence and keep interest rates on government debt low.

Each side of the debate argued that recent experience refuted the other side’s claims. Austerity proponents argued that the persistence of high unemployment despite the fiscal stimulus programs adopted by the United States and other major economies in 2009 showed that stimulus doesn’t work. Stimulus advocates argued that these programs were simply inadequate in size, pointing out that many economists had warned of their inadequacy from the start. Stimulus advocates further argued that warnings about the dangers of deficits were overblown, that far from rising, borrowing costs for Japan, the United States, and Britain—

By 2014, the intellectual debate seemed to have gone mostly against the advocates of austerity. Research at the International Monetary Fund and elsewhere seemed to support warnings that austerity policies depress output and employment, especially when there is little room for interest rates to fall. Interest rates in countries that borrow in their own currencies remained low despite years of high budget deficits—

The Lesson of the Post-Crisis Slump

Almost all major economies had great difficulty dealing with the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis—

Clearly, then, the best way to avoid the terrible problems that arise after a financial crisis is not to have a crisis in the first place. How can you do that? In part, one might hope, through better regulation of financial institutions. We turn next to attempts at regulatory reform.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: If Only It Were the 1930s

If Only It Were the 1930s

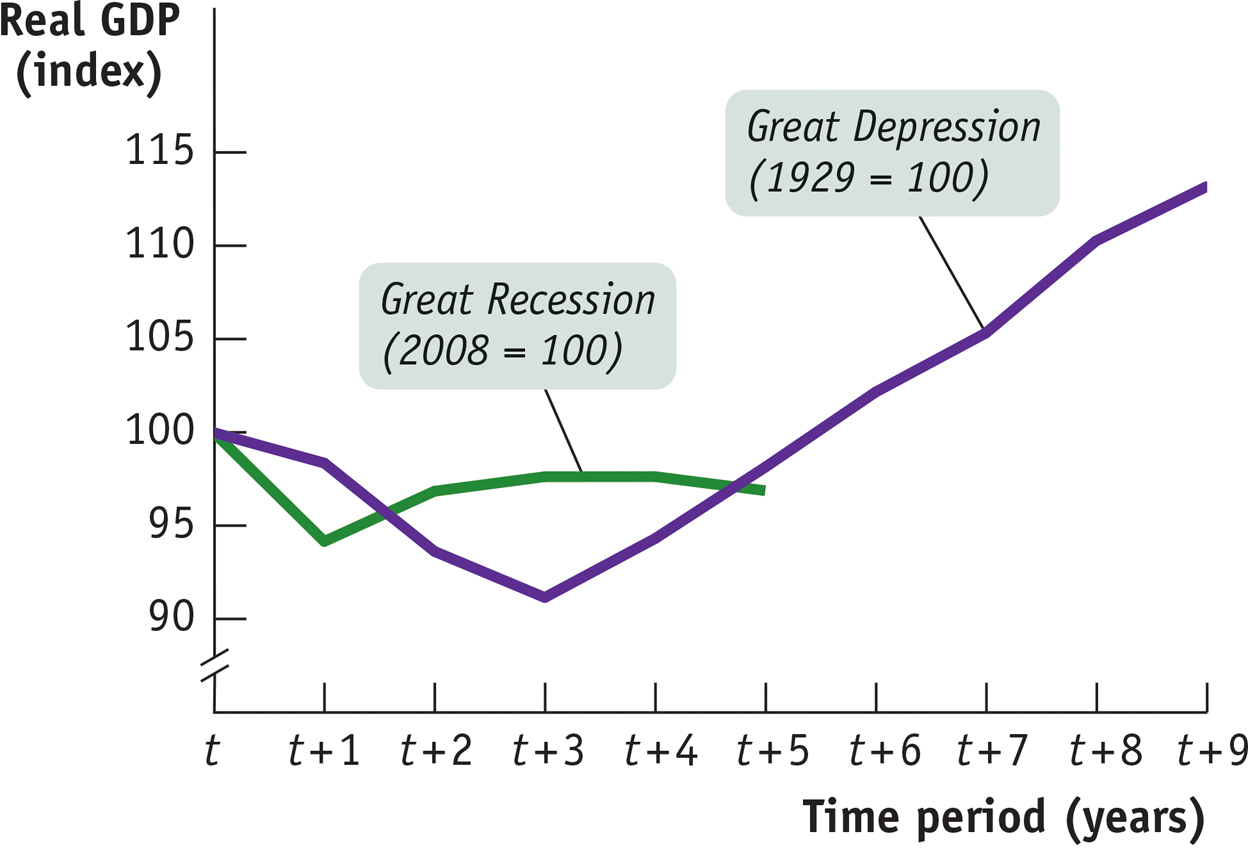

In the United States, the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis was terrible, but at least you can say that it was a lot better than what happened during the Great Depression, when real GDP fell by a third. In Europe, however, you can’t even say that. Partly that’s because the Great Depression wasn’t as severe in Europe as it was in the United States. But it’s also due to the fact that Europe has failed to stage a convincing recovery from the 2008 crisis, sliding back into recession in 2011. As a result, while the initial slump wasn’t as deep as in the 1930s, by the time of writing Europe was actually doing worse than it did in the 1930s.

17-9

Real GDP in Europe, Pre-

Figure 17-9 shows the painful comparison. The purple line shows real GDP in Western Europe from 1929 onwards, while the green line shows real GDP in the eurozone starting in 2008; in each case the pre-

As a result, by late 2014 Europe was, incredibly, significantly behind where it was at this point in the 1930s, prompting the British economic historian Nicholas Crafts to publish a widely cited article with the title “The Eurozone: If Only It Were the 1930s.”

We can attribute Europe’s terrible performance since 2008 in part to policy mistakes and in part to the straitjacket created by the euro itself. However one apportions the blame, Europe’s woes demonstrate the awesome damage financial crises can do.

Quick Review

Economic damage from the financial crisis of 2008 was both large and prolonged. Aftershocks from the crisis continue to shake the world economy.

The world’s two largest economies, the United States and the European Union, suffered severe downturns, shrinking more than 5%, followed by relatively slow recoveries. The severe slump and the slow recovery were very bad news for workers.

The persistence of economic difficulties after the 2008 financial crisis led to severe solvency concerns for several European countries. A fierce debate erupted over whether fiscal stimulus or fiscal austerity was the right policy prescription, which the stimulus advocates appear to be winning.

17-4

Question 17.6

In November 2011, the government of France announced that it was reducing its forecast for economic growth in 2012. It was also reducing its estimates of tax revenue for 2012, since a weaker economy would mean smaller tax receipts. To offset the effect of lower revenue on the budget deficit, the government also announced a new package of tax increases and spending cuts. Which side of the stimulus–

austerity debate was France taking? According to standard macroeconomics, a government should adopt expansionary policies to increase aggregate demand to address an economic slump. France, however, did just the opposite, responding to a weaker economy with a contractionary fiscal policy that would make the economy even weaker. This shows that the French government had adopted the austerity view, believing that it was more important to try to assure markets of its solvency than to support the economy.

Solutions appear at back of book.