Consensus and Conflict in Modern Macroeconomics

The 1970s and the first half of the 1980s were a stormy period for the U.S. economy (and for other major economies, too). There was a severe recession in 1974–

The Great Moderation is the period from 1985 to 2007 when the U.S. economy experienced relatively small fluctuations and low inflation.

After about 1985, however, the economy settled down. The recession of 1990–

The Great Moderation consensus combines a belief in monetary policy as the main tool of stabilization, with skepticism toward the use of fiscal policy, and an acknowledgement of the policy constraints imposed by the natural rate of unemployment and the political business cycle.

The Great Moderation was, unfortunately, followed by the Great Recession, the severe and persistent slump that followed the 2008 financial crisis. We’ll talk shortly about the policy disputes caused by the Great Recession. First, however, let’s examine the apparent consensus that emerged during the Great Moderation, which we call the Great Moderation consensus. It combines a belief in monetary policy as the main tool of stabilization, with skepticism toward the use of fiscal policy, and an acknowledgement of the policy constraints imposed by the natural rate of unemployment and the political business cycle.

To understand where the Great Moderation consensus came from and what still remains in dispute, we’ll look at how macroeconomists have changed their answers to five key questions about macroeconomic policy. The five questions and the various answers given by schools of macroeconomics over the decades are summarized in Table 18-1. (In the table, new classical economics is subsumed under classical economics, and new Keynesian economics is subsumed under the Great Moderation consensus.) Notice that classical macroeconomics said no to each question; basically, classical macroeconomists didn’t think macroeconomic policy could accomplish very much. But let’s go through the questions one by one.

18-1

Five Key Questions About Macroeconomic Policy

|

|

Classical macroeconomics |

Keynesian macroeconomics |

Monetarism |

Great Moderation consensus |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Is expansionary monetary policy helpful in fighting recessions? |

No |

Not very |

Yes |

Yes, except in special circumstances |

|

2. |

Is expansionary fiscal policy effective in fighting recessions? |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

3. |

Can monetary and/or fiscal policy reduce unemployment in the long run? |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

4. |

Should fiscal policy be used in a discretionary way? |

No |

Yes |

No |

No, except possibly in special circumstances |

|

5. |

Should monetary policy be used in a discretionary way? |

No |

Yes |

No |

Disputed |

TABLE 18-

Question 1: Is Expansionary Monetary Policy Helpful in Fighting Recessions?

As we’ve seen, classical macroeconomists generally believed that expansionary monetary policy was ineffective or even harmful in fighting recessions. In the early years of Keynesian economics, macroeconomists weren’t against monetary expansion during recessions, but they tended to believe that it was of doubtful effectiveness. Milton Friedman and his followers convinced economists that monetary policy is effective after all.

Nearly all macroeconomists now agree that monetary policy can be used to shift the aggregate demand curve and to reduce economic instability. The classical view that changes in the money supply affect only aggregate prices, not aggregate output, has few supporters today. The view held by early Keynesian economists—

Question 2: Is Expansionary Fiscal Policy Effective in Fighting Recessions?

Classical macroeconomists were, if anything, even more opposed to fiscal expansion than monetary expansion. Keynesian economists, on the other hand, gave fiscal policy a central role in fighting recessions. Monetarists argued that fiscal policy was ineffective if the money supply was held constant. But that strong view has become relatively rare.

Most macroeconomists now agree that fiscal policy, like monetary policy, can shift the aggregate demand curve. Most macroeconomists also agree that the government should not seek to balance the budget regardless of the state of the economy: they agree that the role of the budget as an automatic stabilizer helps keep the economy on an even keel.

Question 3: Can Monetary and/or Fiscal Policy Reduce Unemployment in the Long Run?

Classical macroeconomists didn’t believe the government could do anything about unemployment. Some Keynesian economists moved to the opposite extreme, arguing that expansionary policies could be used to achieve a permanently low unemployment rate, perhaps at the cost of some inflation. Monetarists believed that unemployment could not be kept below the natural rate.

Almost all macroeconomists now accept the natural rate hypothesis. This hypothesis leads them to accept sharp limits to what monetary and fiscal policy can accomplish. Effective monetary and fiscal policy, most macroeconomists believe, can limit the size of fluctuations of the actual unemployment rate around the natural rate, but they can’t be used to keep unemployment below the natural rate.

Question 4: Should Fiscal Policy Be Used in a Discretionary Way?

As we’ve already seen, views about the effectiveness of fiscal policy have gone back and forth, from rejection by classical macroeconomists, to a positive view by Keynesian economists, to a negative view once again by monetarists. Today most macroeconomists believe that tax cuts and spending increases are at least somewhat effective in increasing aggregate demand.

Many, but not all, macroeconomists, however, believe that discretionary fiscal policy is usually counterproductive, for the reasons discussed in Chapter 13: the lags in adjusting fiscal policy mean that, all too often, policies intended to fight a slump end up intensifying a boom.

As a result, the macroeconomic consensus gives monetary policy the lead role in economic stabilization. Some, but not all, economists believe that fiscal policy must be brought back into the mix under special circumstances, in particular when interest rates are at or near the zero lower bound and the economy is in a liquidity trap. As we’ll see shortly, the proper role of fiscal policy became a huge point of contention after 2008.

Question 5: Should Monetary Policy Be Used in a Discretionary Way?

Classical macroeconomists didn’t think that monetary policy should be used to fight recessions; Keynesian economists didn’t oppose discretionary monetary policy, but they were skeptical about its effectiveness. Monetarists argued that discretionary monetary policy was doing more harm than good. Where are we today? This remains an area of dispute. Today, under the Great Moderation consensus, most macreconomists agree on these three points:

Monetary policy should play the main role in stabilization policy.

The central bank should be independent, insulated from political pressures, in order to avoid a political business cycle.

Discretionary fiscal policy should be used sparingly, both because of policy lags and because of the risks of a political business cycle.

However, the Great Moderation was upended by events that posed very difficult questions—

Crisis and Aftermath

The Great Recession shattered any sense among macroeconomists that they had entered a permanent era of agreement over key policy questions. Given the nature of the slump, however, this should not have come as a surprise. Why? Because the severity of the slump arguably made the policies that seemed to work during the Great Moderation inadequate.

Under the Great Moderation consensus, there had been broad agreement that the job of stabilizing the economy was best carried out by having the Federal Reserve and its counterparts abroad raise or lower interest rates as the economic situation warranted. But what should be done if the economy is deeply depressed, but the interest rates the Fed normally controls are already close to zero and can go no lower (that is, when the economy is in a liquidity trap)? Some economists called for the aggressive use of discretionary fiscal policy and/or unconventional monetary policies that might achieve results despite the zero lower bound. Others strongly opposed these measures, arguing either that they would be ineffective or that they would produce undesirable side effects.

The Debate over Fiscal Policy In 2009 a number of governments, including that of the United States, responded with expansionary fiscal policy, or “stimulus,” generally taking the form of a mix of temporary spending measures and temporary tax cuts. From the start, however, these efforts were highly controversial.

Supporters of fiscal stimulus offered three main arguments for breaking with the normal presumption against discretionary fiscal policy:

They argued that discretionary fiscal expansion was needed because the usual tool for stabilizing the economy, monetary policy, could no longer be used now that interest rates were near zero.

They argued that one normal concern about expansionary fiscal policy—

that deficit spending would drive up interest rates, crowding out private investment spending— was unlikely to be a problem in a depressed economy. Again, this was because interest rates were close to zero and likely to stay there as long as the economy was depressed. Finally, they argued that another concern about discretionary fiscal policy—

that it might take a long time to get going— was less of a concern than usual given the likelihood that the economy would be depressed for an extended period.

These arguments generally won the day in early 2009. However, opponents of fiscal stimulus raised two main objections:

They argued that households and firms would see any rise in government spending as a sign that tax burdens were likely to rise in the future, leading to a fall in private spending that would undo any positive effect. (This is the Ricardian equivalence argument that we encountered in Chapter 13.)

They also warned that spending programs might undermine investors’ faith in the government’s ability to repay its debts, leading to an increase in long-

term interest rates despite loose monetary policy.

In fact, by 2010 a number of economists were arguing that the best way to boost the economy was actually to cut government spending, which they argued would increase private-

As is often the case with major disputes in economics, the argument over fiscal policy went on for years, with some critics of fiscal policy still defending their position when this book went to press. It seems fair, however, to say that among economists a more or less Keynesian view of the effects of fiscal policy came to prevail. Careful statistical studies at the International Monetary Fund and elsewhere showed that austerity policies have historically been followed by contraction, not expansion. Recent experience, in which countries like Spain and Greece that were forced into severe austerity also experienced severe slumps, seemed to confirm that observation.

Furthermore, it was clear that those who had predicted a sharp rise in U.S. interest rates due to budget deficits, leading to conventional crowding out, had been wrong: U.S. long-

The Debate over Monetary Policy As we’ve learned, a central bank that wants to increase aggregate demand normally does this by buying short-

In 2008–

The policy of quantitative easing was controversial, facing criticisms both from those who believed that the Fed was doing too much and from those who believed it was doing too little. Those who believed that the Fed was doing too much were concerned about possible future inflation; they argued that the Fed would find its unconventional measures hard to reverse as the economy recovered and that the end result would be a much too expansionary monetary policy. Opponents of quantitative easing were not shy about making their views heard: in October 2010 a Who’s Who of conservative economists and major investors issued an open letter calling on Ben Bernanke to call off the policy, which they warned could lead to a “debased” dollar.

Critics from the other side argued that the Fed’s actions were likely to be ineffective: long-

Many of those calling on the Fed for even more active policy advocated an official rise in the Fed’s inflation target. Recall from Chapters 8 and 10 the distinction between the nominal interest rate, which is the number normally cited, and the real interest rate—

Such proposals, however, led to fierce disputes. Some economists pointed out that the Fed had fought hard to drive inflation expectations down and argued that changing course would undermine hard-

At the time of writing, these disputes were still raging, and it seemed unlikely that a new consensus about macroeconomic policy would emerge any time soon.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Lats of Luck

Lats of Luck

The Brookings Institution in Washington, DC, is one of the most influential U.S. think tanks, especially on economic issues. In particular, its twice-

Even some of the panelists were bemused, asking why Brookings was devoting so much time to a country with a population of just 2 million—

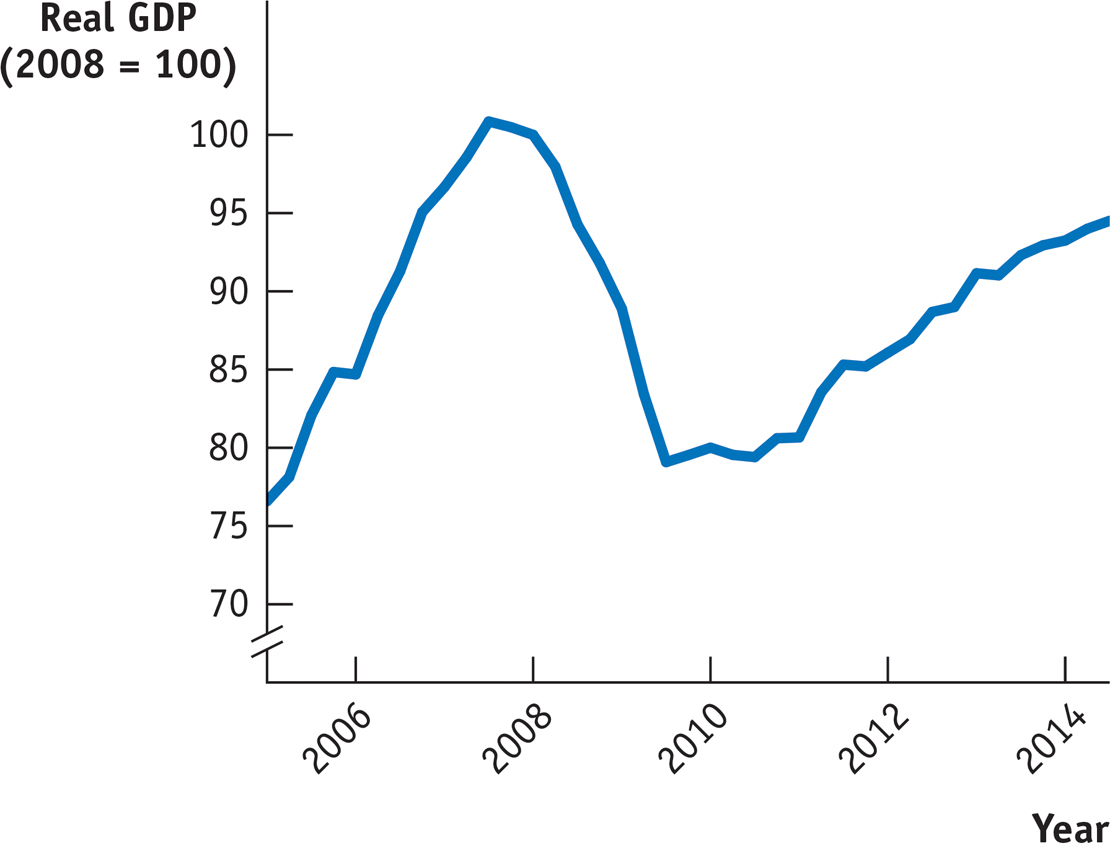

18-6

Real GDP for Latvia, 2005–

Figure 18-6, which shows Latvia’s real GDP since 2005, helps explain both why the country is cited as a success story for austerity policies and why the extent of success was a subject of dispute. In the years before the crisis Latvia was experiencing rapid growth, fueled by large inflows of capital. When these flows dried up, the country experienced a severe slump—

Instead, however, the Latvian government kept the value of the lats fixed in terms of the euro, and adopted the euro itself in 2014. Meanwhile, it sharply cut spending in an attempt to shore up confidence. And as you can see in Figure 18-6, Latvia’s economy eventually began to recover from its slump, which supporters of austerity claimed vindicated its policy. Critics, however, pointed out that as late as 2014 output was still below its pre-

So whose case did Latvia support? Possibly neither. As both the authors and discussants of the Blanchard paper noted, Latvia is a relatively poor country—

Quick Review

The Great Moderation, the period of relative economic calm from 1985 to 2007, produced the Great Moderation consensus.

According to the Great Moderation consensus: monetary policy should be the main stabilization tool; to avoid a political business cycle, the central bank should be independent and fiscal policy should not be used, except possibly in exceptional circumstances such as a liquidity trap; and the natural rate of unemployment limits how much policy activism can reduce the unemployment rate.

The Great Moderation consensus was severely challenged by the Great Recession. Active fiscal policy was revived given the ineffectiveness of monetary policy in the midst of a liquidity trap. Fiercely debated, fiscal stimulus in the United States failed to deliver a significant fall in unemployment. Critics cited this as evidence that fiscal policy doesn’t work, while supporters countered that the size of the stimulus was too small. However, crowding out failed to materialize as critics had warned that it would.

Monetary policy was also deeply controversial in the wake of the Great Recession, as the Fed pursued “quantitative easing” and other unconventional policies. Critics claimed the Fed was doing too much and too little, while some advocated the adoption of a higher inflation target to push the real interest rate down.

18-5

Question 18.6

Why did the Great Recession lead to the decline of the Great Moderation consensus? Given events, why is it predictable that a new consensus has not emerged?

The liquidity trap brought on by the Great Recession greatly diminished the Great Moderation consensus because it considered monetary policy to be the main policy tool and monetary policy was now largely ineffective. The continuing disagreements over fiscal policy were now brought to the forefront as fiscal policy was used by policy makers to support their deeply depressed economies. A new consensus is unlikely to emerge anytime soon because results of the various policies have been unclear or disappointing: fiscal stimulus has failed to bring down unemployment substantially (although some say the stimulus was too small); conventional monetary policy does not work; and the Fed’s unconventional monetary policy seemed to have relatively little effect.

Solution appears at back of book.