Exchange Rate Policy

The nominal exchange rate, like other prices, is determined by supply and demand. Unlike the price of wheat or oil, however, the exchange rate is the price of a country’s money (in terms of another country’s money). Money isn’t a good or service produced by the private sector; it’s an asset whose quantity is determined by government policy. As a result, governments have much more power to influence nominal exchange rates than they have to influence ordinary prices.

The nominal exchange rate is a very important price for many countries: the exchange rate determines the price of imports and the price of exports; in economies where exports and imports are large percentages of GDP, movements in the exchange rate can have major effects on aggregate output and the aggregate price level. What do governments do with their power to influence this important price?

The answer is, it depends. At different times and in different places, governments have adopted a variety of exchange rate regimes. Let’s talk about these regimes, how they are enforced, and how governments choose a regime. (From now on, we’ll adopt the convention that we mean the nominal exchange rate when we refer to the exchange rate.)

Exchange Rate Regimes

An exchange rate regime is a rule governing policy toward the exchange rate.

A country has a fixed exchange rate when the government keeps the exchange rate against some other currency at or near a particular target.

A country has a floating exchange rate when the government lets market forces determine the exchange rate.

An exchange rate regime is a rule governing policy toward the exchange rate. There are two main kinds of exchange rate regimes. A country has a fixed exchange rate when the government keeps the exchange rate against some other currency at or near a particular target. For example, Hong Kong has an official policy of setting an exchange rate of HK$7.80 per US$1. In contrast, a country has a floating exchange rate when the government lets market forces determine the exchange rate. This is the policy followed by Britain, Canada, and the United States.

Fixed exchange rates and floating exchange rates aren’t the only possibilities. At various times, countries have adopted compromise policies that lie somewhere between fixed and floating exchange rates. These include exchange rates that are fixed at any given time but are adjusted frequently, exchange rates that aren’t fixed but are “managed” by the government to avoid wide swings, and exchange rates that float within a “target zone” but are prevented from leaving that zone. In this book, however, we’ll focus on the two main exchange rate regimes.

The immediate dilemma posed by a fixed exchange rate is how a government can fix the exchange rate when the exchange rate is determined by supply and demand.

How Can an Exchange Rate Be Held Fixed?

To understand how it is possible for a country to fix its exchange rate, let’s consider a hypothetical country, Genovia, which for some reason has decided to fix the value of its currency, the geno, at US$1.50.

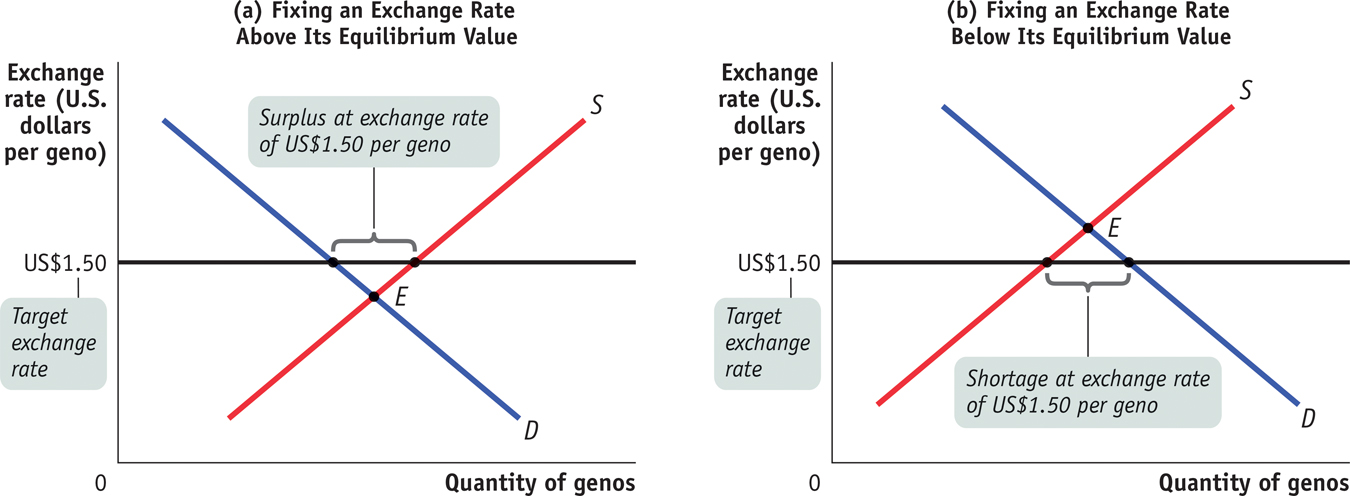

The obvious problem is that $1.50 may not be the equilibrium exchange rate in the foreign exchange market: the equilibrium rate may be either higher or lower than the target exchange rate. Figure 19-10 shows the foreign exchange market for genos, with the quantities of genos supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis and the exchange rate of the geno, measured in U.S. dollars per geno, on the vertical axis. Panel (a) shows the case in which the equilibrium value of the geno is below the target exchange rate. Panel (b) shows the case in which the equilibrium value of the geno is above the target exchange rate.

19-10

Exchange Market Intervention

Consider first the case in which the equilibrium value of the geno is below the target exchange rate. As panel (a) shows, at the target exchange rate of $1.50 per geno, there is a surplus of genos in the foreign exchange market, which would normally push the value of the geno down. How can the Genovian government support the value of the geno to keep the rate where it wants? There are three possible answers, all of which have been used by governments at some point.

A government purchase or sale of currency in the foreign exchange market is an exchange market intervention.

Foreign exchange reserves are stocks of foreign currency that governments maintain to buy their own currency on the foreign exchange market.

One way the Genovian government can support the geno is to “soak up” the surplus of genos by buying its own currency in the foreign exchange market. A government purchase or sale of currency in the foreign exchange market is called an exchange market intervention. To buy genos in the foreign exchange market, of course, the Genovian government must have U.S. dollars to exchange for genos. In fact, most countries maintain foreign exchange reserves, stocks of foreign currency (usually U.S. dollars or euros) that they can use to buy their own currency to support its price.

We mentioned earlier in the chapter that an important part of international capital flows is the result of purchases and sales of foreign assets by governments and central banks. Now we can see why governments sell foreign assets: they are supporting their currency through exchange market intervention. As we’ll see in a moment, governments that keep the value of their currency down through exchange market intervention must buy foreign assets. First, however, let’s talk about the other ways governments fix exchange rates.

A second way for the Genovian government to support the geno is to try to shift the supply and demand curves for the geno in the foreign exchange market. Governments usually do this by changing monetary policy. For example, to support the geno the Genovian central bank can raise the Genovian interest rate. This will increase capital flows into Genovia, increasing the demand for genos, at the same time that it reduces capital flows out of Genovia, reducing the supply of genos. So, other things equal, an increase in a country’s interest rate will increase the value of its currency.

Foreign exchange controls are licensing systems that limit the right of individuals to buy foreign currency.

Third, the Genovian government can support the geno by reducing the supply of genos to the foreign exchange market. It can do this by requiring domestic residents who want to buy foreign currency to get a license and giving these licenses only to people engaging in approved transactions (such as the purchase of imported goods the Genovian government thinks are essential). Licensing systems that limit the right of individuals to buy foreign currency are called foreign exchange controls. Other things equal, foreign exchange controls increase the value of a country’s currency.

So far we’ve been discussing a situation in which the government is trying to prevent a depreciation of the geno. Suppose, instead, that the situation is as shown in panel (b) of Figure 19-10, where the equilibrium value of the geno is above the target exchange rate of $1.50 per geno and there is a shortage of genos. To maintain the target exchange rate, the Genovian government can apply the same three basic options in the reverse direction. It can intervene in the foreign exchange market, in this case selling genos and acquiring U.S. dollars, which it can add to its foreign exchange reserves. It can reduce interest rates to increase the supply of genos and reduce the demand. Or it can impose foreign exchange controls that limit the ability of foreigners to buy genos. All of these actions, other things equal, will reduce the value of the geno.

As we said, all three techniques have been used to manage fixed exchange rates. But we haven’t said whether fixing the exchange rate is a good idea. In fact, the choice of exchange rate regime poses a dilemma for policy makers, because fixed and floating exchange rates each have both advantages and disadvantages.

The Exchange Rate Regime Dilemma

Few questions in macroeconomics produce as many arguments as that of whether a country should adopt a fixed or a floating exchange rate. The reason there are so many arguments is that both sides have a case.

To understand the case for a fixed exchange rate, consider for a moment how easy it is to conduct business across state lines in the United States. There are a number of things that make interstate commerce trouble-

By contrast, a dollar isn’t a dollar in transactions between New York City and Toronto. The exchange rate between the Canadian dollar and the U.S. dollar fluctuates, sometimes widely. If a U.S. firm promises to pay a Canadian firm a given number of U.S. dollars a year from now, the value of that promise in Canadian currency can vary by 10% or more. This uncertainty has the effect of deterring trade between the two countries. So one benefit of a fixed exchange rate is certainty about the future value of a currency.

From Bretton Woods to the Euro

In 1944, while World War II was still raging, representatives of Allied nations met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to establish a postwar international monetary system of fixed exchange rates among major currencies. The system was highly successful at first, but it broke down in 1971. After a confusing interval during which policy makers tried unsuccessfully to establish a new fixed exchange rate system, by 1973 most economically advanced countries had moved to floating exchange rates.

In Europe, however, many policy makers were unhappy with floating exchange rates, which they believed created too much uncertainty for business. From the late 1970s onward they tried several times to create a system of more or less fixed exchange rates in Europe, culminating in an arrangement known as the Exchange Rate Mechanism. (The Exchange Rate Mechanism was, strictly speaking, a “target zone” system—

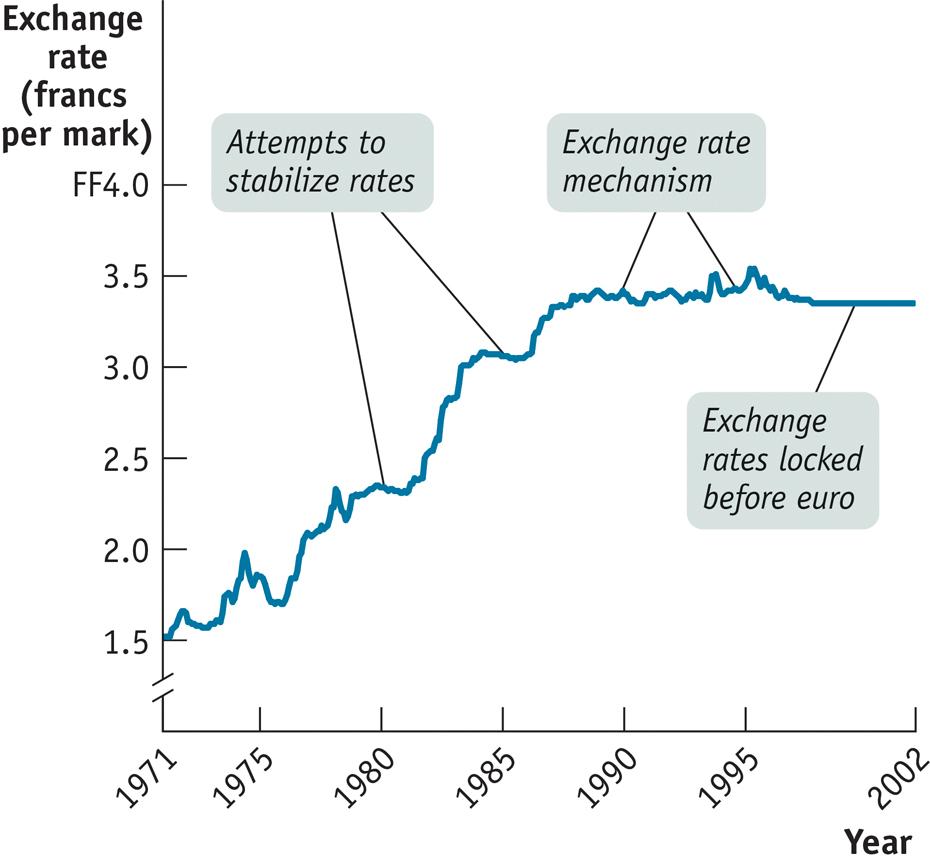

Figure 19-11 illustrates the history of European exchange rate arrangements. It shows the exchange rate between the French franc and the German mark, measured as francs per mark, from 1971 until their replacement by the euro. The exchange rate fluctuated widely at first. The plateaus you can see in the data—

19-11

The Road to the Euro

In 1999 the exchange rate was locked—no further fluctuations were allowed as the countries prepared to switch from francs and marks to the euro. At the end of 2001, the franc and the mark ceased to exist.

The transition to the euro has not been without costs. Countries that adopted the euro sacrificed some important policy tools: they could no longer tailor monetary policy to their specific economic circumstances, and they could no longer lower their costs relative to other European nations simply by letting their currencies depreciate.

At the time this book went to press, the euro area was under serious stress, with several nations—

There is also, in some cases, an additional benefit to adopting a fixed exchange rate: by committing itself to a fixed rate, a country is also committing itself not to engage in inflationary policies. For example, in 1991 Argentina, which has a long history of irresponsible policies leading to severe inflation, adopted a fixed exchange rate of US$1 per Argentine peso in an attempt to commit itself to non-

The point is that there is some economic value in having a stable exchange rate. Indeed, as the previous For Inquiring Minds explains, the presumed benefits of stable exchange rates motivated the international system of fixed exchange rates created after World War II. It was also a major reason for the creation of the euro.

However, there are also costs to fixing the exchange rate. To stabilize an exchange rate through intervention, a country must keep large quantities of foreign currency on hand—

So there’s a dilemma. Should a country let its currency float, which leaves monetary policy available for macroeconomic stabilization but creates uncertainty for business? Or should it fix the exchange rate, which eliminates the uncertainty but means giving up monetary policy, adopting exchange controls, or both? Different countries reach different conclusions at different times. Most European countries, except for Britain, have long believed that exchange rates among major European economies, which do most of their international trade with each other, should be fixed. But Canada seems happy with a floating exchange rate with the United States, even though the United States accounts for most of Canada’s trade.

Fortunately we don’t have to resolve this dilemma. For the rest of the chapter, we’ll take exchange rate regimes as given and ask how they affect macroeconomic policy.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: China Pegs the Yuan

China Pegs the Yuan

In the early years of the twenty-

To keep the rate fixed, China had to engage in large-

To get a sense of how big these totals are, in 2010 China’s GDP was approximately $5.9 trillion. This means that in 2010 China bought U.S. dollars and other currencies equal to about 7.5% of its GDP, making its accumulated reserves equal to more than half its GDP. That’s as if the U.S. government had bought well over $1 trillion worth of yen and euros in a single year, even though it was already sitting on an $8 trillion pile of foreign currencies. Not surprisingly, China’s exchange rate policy led to some friction with its trading partners, who felt that it had the effect of subsidizing Chinese exports.

Over the next few years, however, China’s current account surplus dwindled. Partly this reflected rising Chinese wages, which made China less competitive, and partly it reflected the rise of new competitors, like Vietnam. At the time of writing, friction over China’s exchange rate policy was greatly diminished.

Quick Review

Countries choose different exchange rate regimes. The two main regimes are fixed exchange rates and floating exchange rates.

Exchange rates can be fixed through exchange market intervention, using foreign exchange reserves. Countries can also use domestic policies to shift supply and demand in the foreign exchange market (usually monetary policy), or they can impose foreign exchange controls.

Choosing an exchange rate regime poses a dilemma. Stable exchange rates are good for business. But holding large foreign exchange reserves is costly, using domestic policy to fix the exchange rate makes it hard to pursue other objectives, and foreign exchange controls distort incentives.

19-3

Question 19.5

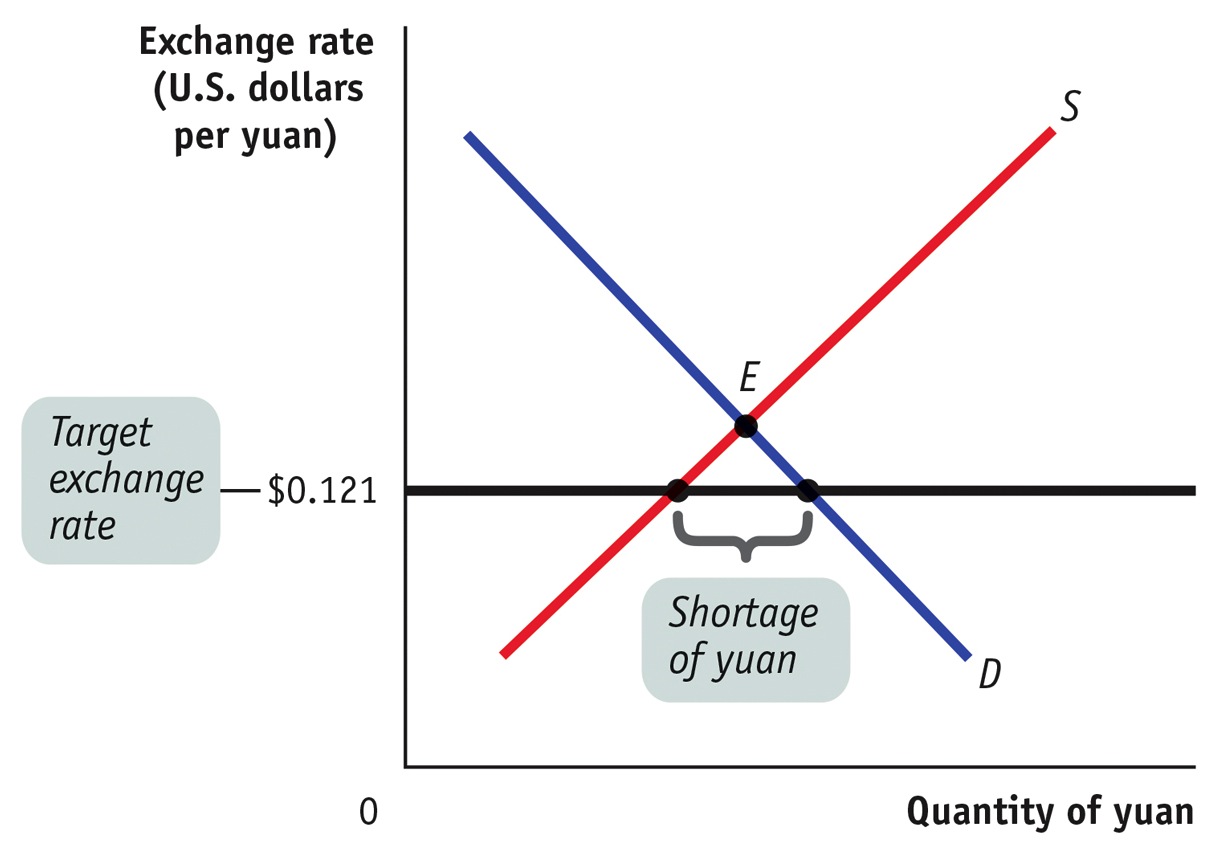

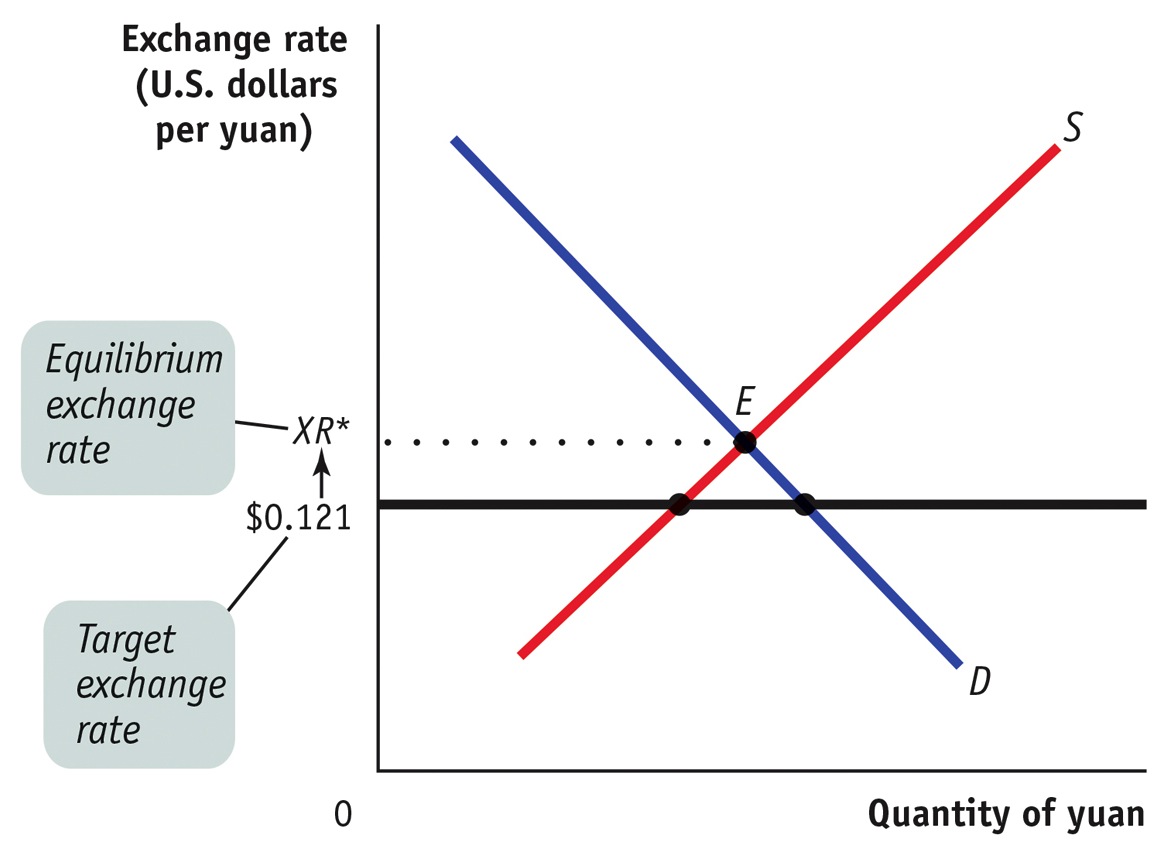

Draw a diagram, similar to Figure 19-10, representing the foreign exchange situation of China when it kept the exchange rate fixed. (Hint: Express the exchange rate as U.S. dollars per yuan.) Then show with a diagram how each of the following policy changes might eliminate the disequilibrium in the market.

An appreciation of the yuan

Placing restrictions on foreigners who want to invest in China

Removing restrictions on Chinese who want to invest abroad

Imposing taxes on Chinese exports, such as shipments of clothing, that are causing a political backlash in the importing countries

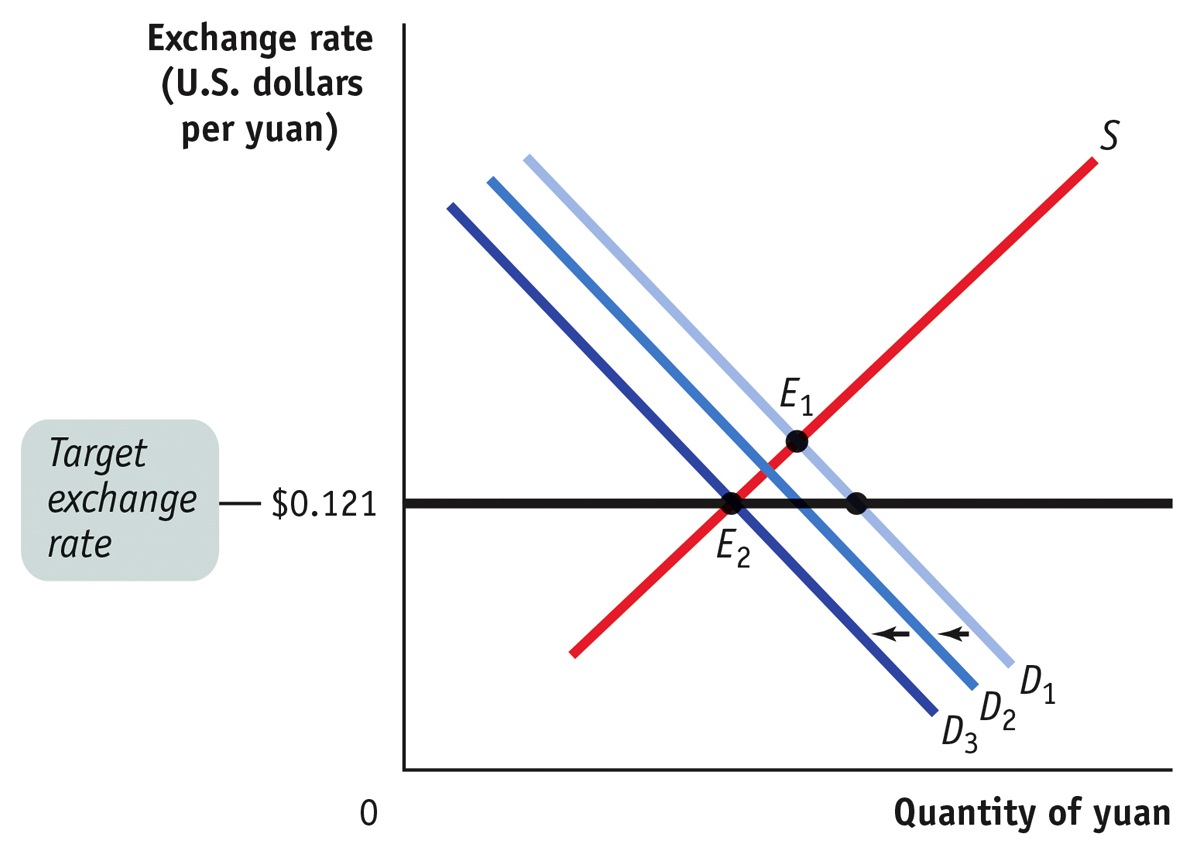

The accompanying diagram shows the supply of and demand for the yuan, with the U.S. dollar price of the yuan on the vertical axis. In 2005, prior to the revaluation, the exchange rate was pegged at 8.28 yuan per U.S. dollar or, equivalently, 0.121 U.S. dollars per yuan ($0.121). At the target exchange rate of $0.121, the quantity of yuan demanded exceeded the quantity of yuan supplied, creating the shortage depicted in the diagram. Without any intervention by the Chinese government, the U.S. dollar price of the yuan would be bid up, causing an appreciation of the yuan. The Chinese government, however, intervened to prevent this appreciation.

If the exchange rate were allowed to move freely, the U.S. dollar price of the exchange rate would move toward the equilibrium exchange rate (labeled XR* in the accompanying diagram). This would occur as a result of the shortage, when buyers of the yuan would bid up its U.S. dollar price. As the exchange rate increases, the quantity of yuan demanded would fall and the quantity of yuan supplied would increase. If the exchange rate were to increase to XR*, the disequilibrium would be entirely eliminated.

Placing restrictions on foreigners who want to invest in China would reduce the demand for the yuan, causing the demand curve to shift in the accompanying diagram from D1 to something like D2. This would cause a reduction in the shortage of the yuan. If demand fell to D3, the disequilibrium would be completely eliminated.

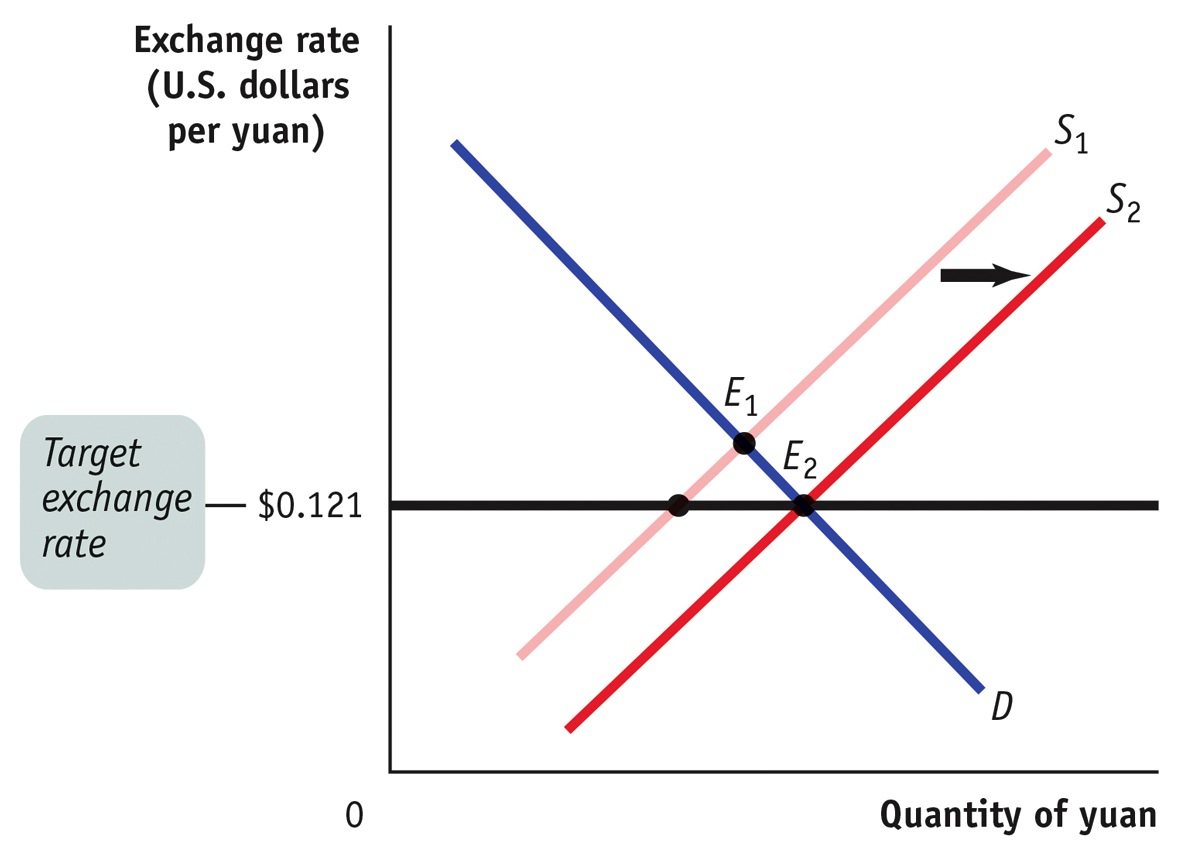

Removing restrictions on Chinese who wish to invest abroad would cause an increase in the supply of the yuan and a rightward shift in the supply curve. This increase in supply would also cause a reduction in the size of the shortage. If, for example, supply increased from S1 to S2, the disequilibrium would be eliminated completely in the accompanying diagram.

Imposing a tax on exports (Chinese goods sold to foreigners) would raise the price of these goods and decrease the amount of Chinese goods purchased. This would also decrease the demand for the yuan. The graphical analysis here is virtually identical to that found in the figure accompanying part b.

Solutions appear at back of book.