External Costs and Benefits

An external cost is an uncompensated cost that an individual or firm imposes on others.

The environmental costs of pollution are the best known and most important example of an external cost—an uncompensated cost that an individual or firm imposes on others. In a modern economy there are many examples of an external cost that an individual or firm imposes on others. A very familiar one is the external cost of traffic congestion: an individual who chooses to drive during rush hour increases congestion and has no incentive to take into account the inconvenience inflicted on other drivers. Another familiar example is the cost created by people who text while driving, increasing the risk of accidents that will harm others as well as themselves (see the upcoming For Inquiring Minds).

Pollution leads to an external cost because in the absence of government intervention those who decide how much pollution to create have no incentive to take into account the costs of pollution that they impose on others. In the case of air pollution from a coal-

An external benefit is a benefit that an individual or firm confers on others without receiving compensation.

External costs and benefits are known as externalities. External costs are negative externalities, and external benefits are positive externalities.

We’ll see later in this chapter that there are also important examples of external benefits, benefits that individuals or firms confer on others without receiving compensation. For example, when you get a flu shot, you are less likely to pass on the flu virus to your roommates. Yet you alone incur the monetary cost of the vaccination and the painful jab. Businesses that develop new technologies also generate external benefits, because their ideas often contribute to innovation by other firms.

External costs and benefits are jointly known as externalities, with external costs called negative externalities and external benefits called positive externalities. Externalities can lead to private decisions—

Talking, Texting, and Driving

Why is that person in the car in front of us driving so erratically? Is the driver drunk? No, the driver is talking on the phone or texting.

Traffic safety experts take the risks posed by driving while using a cell phone very seriously: A recent study found a six-

One estimate suggests that talking while driving may be responsible for 3,000 or more traffic deaths each year. And using hands-

The National Safety Council urges people not to use cell-

Why not leave the decision up to the driver? Because the risk posed by driving while using a cell phone isn’t just a risk to the driver; it’s also a safety risk to others—

Pollution: An External Cost

Pollution is a bad thing. Yet most pollution is a side effect of activities that provide us with good things: our air is polluted by power plants generating the electricity that lights our cities, and our rivers are damaged by fertilizer runoff from farms that grow our food. And groundwater contamination may occur from fracking, which also produces cleaner-

Actually, we do. Even highly committed environmentalists don’t think that we can or should completely eliminate pollution—

To see why, we need a framework that lets us think about how much pollution a society should have. We’ll then be able to see why a market economy, left to itself, will produce more pollution than it should. We’ll start by adopting the simplest framework to study the problem—

The Socially Optimal Quantity of Pollution

How much pollution should society allow? We learned in Chapter 9 that “how much” decisions always involve comparing the marginal benefit from an additional unit of something with the marginal cost of that additional unit. The same is true of pollution.

The marginal social cost of pollution is the additional cost imposed on society as a whole by an additional unit of pollution.

The marginal social cost of pollution is the additional cost imposed on society as a whole by an additional unit of pollution.

For example, sulfur dioxide from coal-

The marginal social benefit of pollution is the additional gain to society as a whole from an additional unit of pollution.

The marginal social benefit of pollution is the benefit to society from an additional unit of pollution. This may seem like a confusing concept—

All these methods of reducing pollution have an opportunity cost. That is, avoiding pollution requires using scarce resources that could have been employed to produce other goods and services. So the marginal social benefit of pollution is the goods and services that could be had by society if it tolerated another unit of pollution.

Comparisons between the pollution levels tolerated in rich and poor countries illustrate the importance of the level of the marginal social benefit of pollution in deciding how much pollution a society wishes to tolerate. Because poor countries have a higher opportunity cost of resources spent on reducing pollution than richer countries, they tolerate higher levels of pollution. For example, the World Health Organization has estimated that 3.5 million people in poor countries die prematurely from breathing polluted indoor air caused by burning dirty fuels like wood, dung, and coal to heat and cook—

The socially optimal quantity of pollution is the quantity of pollution that society would choose if all the costs and benefits of pollution were fully accounted for.

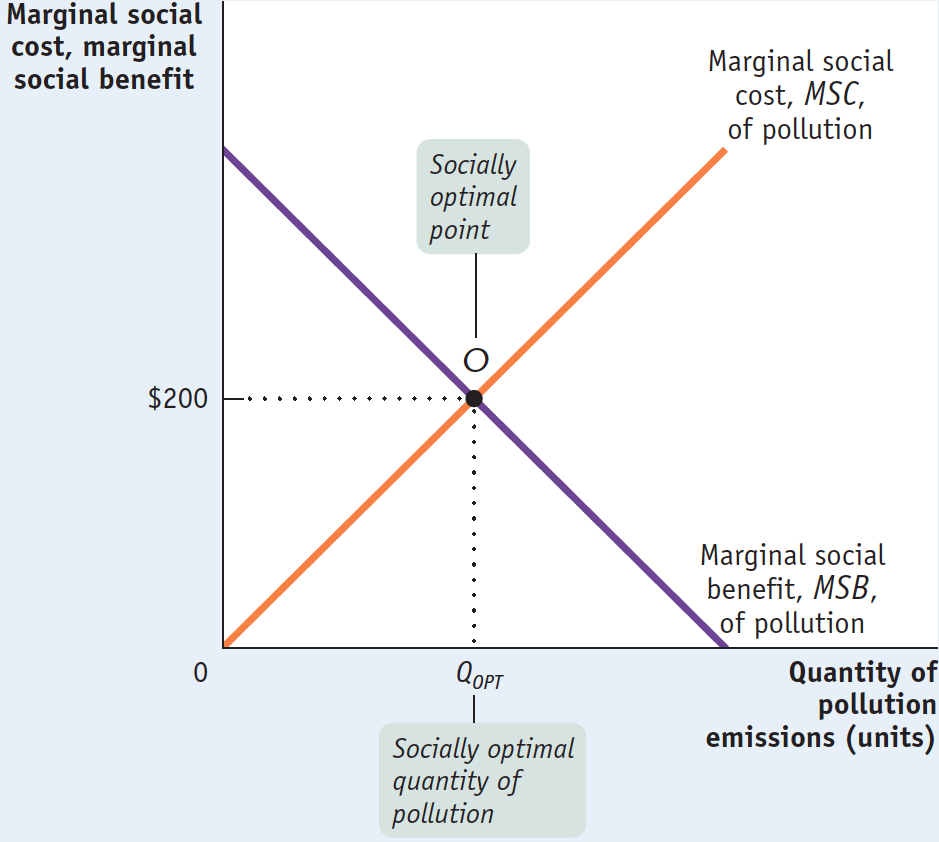

Using hypothetical numbers, Figure 16-1 shows how we can determine the socially optimal quantity of pollution—the quantity of pollution society would choose if all the social costs and benefits were fully accounted for. The upward-

16-1

The Socially Optimal Quantity of Pollution

The socially optimal quantity of pollution in this example isn’t zero. It’s QOPT, the quantity corresponding to point O, where MSB crosses MSC. At QOPT, the marginal social benefit from an additional unit of pollution and its marginal social cost are equalized at $200.

But will a market economy, left to itself, arrive at the socially optimal quantity of pollution? No, it won’t.

Why a Market Economy Produces Too Much Pollution

While pollution yields both benefits and costs to society, in a market economy without government intervention too much pollution will be produced. In that case it is polluters alone—

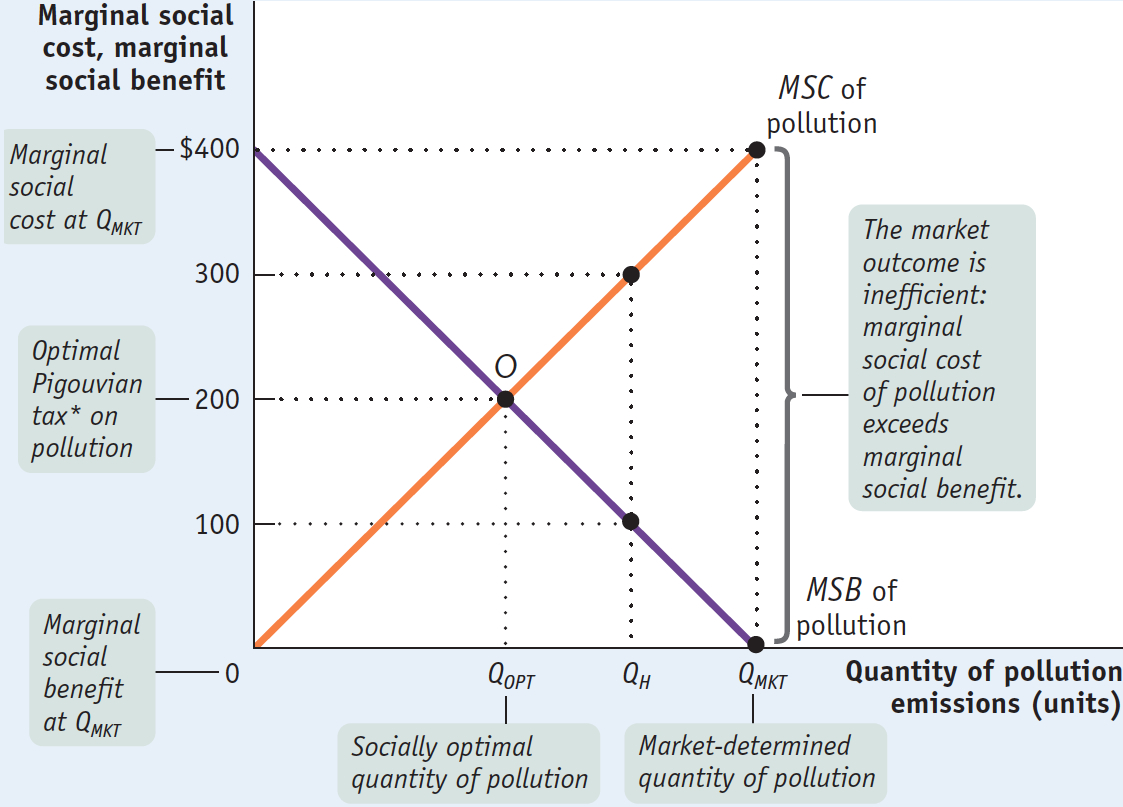

Figure 16-2 shows the result of this asymmetry between who reaps the benefits and who pays the costs. In a market economy without government intervention, since polluters are the only ones making the decisions, only the benefits of pollution are taken into account when choosing how much pollution to produce. So instead of producing the socially optimal quantity, QOPT, the market economy will generate the amount QMKT. At QMKT, the marginal social benefit of an additional unit of pollution is zero, while the marginal social cost of an additional unit is much higher—

16-2

Why a Market Economy Produces Too Much Pollution

Why? Well, take a moment to consider what the polluter would do if he found himself emitting QOPT of pollution. Remember that the MSB curve represents the resources made available by tolerating one more unit of pollution. The polluter would notice that if he increases his emission of pollution by moving down the MSB curve from QOPT to QH, he would gain $200 − $100 = $100. That gain of $100 comes from using less-

The market outcome, QMKT, is inefficient. Recall that an outcome is inefficient if someone could be made better off without someone else being made worse off. At an inefficient outcome, a mutually beneficial trade is being missed. At QMKT, the benefit accruing to the polluter of the last unit of pollution is very low—

So total surplus rises by approximately $400 if the quantity of pollution at QMKT is reduced by one unit. At QMKT, society would be willing to pay the polluter up to $400 not to emit the last unit of pollution, and the polluter would be willing to accept their offer since that last unit gains him virtually nothing. But because there is no means in this market economy for this transaction to take place, an inefficient outcome occurs.

Private Solutions to Externalities

As we’ve just seen, externalities in a market economy cause inefficiency: there is a mutually beneficial trade that is being missed. So can the private sector solve the problem of externalities without government intervention? Will individuals be able to make that deal on their own?

According to the Coase theorem, even in the presence of externalities an economy can always reach an efficient solution as long as transaction costs—the costs to individuals of making a deal—

In an influential 1960 article, the economist and Nobel laureate Ronald Coase pointed out that in an ideal world the private sector could indeed solve the problem of inefficiency caused by externalities. According to the Coase theorem, even in the presence of externalities an economy can always reach an efficient solution provided that the costs of making a deal are sufficiently low. The costs of making a deal are known as transaction costs.

For an illustration of how the Coase theorem might work, consider the case of groundwater contamination caused by drilling. There are two ways a private transaction can address this problem. First, landowners whose groundwater is at risk of contamination can pay drillers to use more-

When individuals take external costs or benefits into account, they internalize the externality.

What Coase argued is that, either way, if transaction costs are sufficiently low, then drillers and landowners can make a mutually beneficial deal. Regardless of how the transaction is structured, the social cost of the pollution is taken into account in decision making. When individuals take externalities into account when making decisions, economists say that they internalize the externality. In that case the outcome is efficient without government intervention.

So why don’t private parties always internalize externalities? The problem is transaction costs in one form or another that prevent an efficient outcome. Here is a sample:

The high cost of communication. Suppose a power plant emits pollution that covers a wide area. The cost of communicating with the many people affected will be very high.

The high cost of making legally binding and timely agreements. What if some landowners band together and pay a driller to reduce groundwater pollution. It can be very expensive to make an effective agreement, requiring lawyers, groundwater tests, engineers, and others. And there is no guarantee that the negotiations will go smoothly or quickly: some landowners may refuse to pay even if their groundwater is protected, while the drillers may hold out for a better deal.

To be sure, there are examples in the real world in which private parties internalize the externalities. Take the case of private communities that set rules for appearances—

In some cases, people do find ways to reduce transaction costs, allowing them to internalize externalities. For example, a house with a junk-

When transaction costs prevent the private sector from dealing with externalities, it is time to look for government solutions. We turn to public policy in the next section.

ECONOMICS in Action: How Much Does Your Electricity Really Cost?

How Much Does Your Electricity Really Cost?

In 2011, three leading economists, Nicholas Z. Muller, Robert Mendelsohn, and William Nordhaus, published a paper drawn from the results of an ambitious study that estimated the external cost of pollution generated by 10,000 pollution sources in the United States, broken down by industry. In it they model the costs to society of emissions of six major pollutants: sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, ammonia, fine particulate matter, and coarse particulate matter. The costs took a variety of forms, from harmful effects on health to reduced agricultural yields. In the case of the electricity-

An industry with a TEC/TVC ratio greater than 1 indicates that the external cost of pollution exceeds the value created. In other words, a ratio greater than 1 means that a marginal reduction in both industry output and its ensuing pollution increases total social welfare. But as the authors of the study emphasize, this doesn’t mean that the industry should be shut down. Rather, it means that the current level of pollution emitted is too high. A contentious issue in any model of the external cost of greenhouse gases—

So how do you value today the cost imposed on those not yet born? A difficult question, for sure. Economists address this puzzle by using a range of estimates for SCC. For example, in November 2013, the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, the federal agency tasked with protecting the environment, published estimates ranging from $12 to $116 and settled on a cost of $37 per metric ton of carbon dioxide.

Using a relatively conservative estimate of $27 for SCC, Muller, Mendelsohn, and Nordhaus compare the TEC/TVC ratio and the TEC per kilowatt-

|

TEC/TVC |

TEC/kilowatt- |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Coal |

2.83 |

$0.039 |

|

Natural gas |

1.30 |

0.005 |

As you can see, both modes of electricity generation are under-

In response to growing concerns about carbon emissions, in early 2014 the EPA issued rules that limited the amount of carbon emitted by newly constructed coal-

Quick Review

External costs and benefits are known as externalities. Pollution is an example of an external cost, or negative externality; in contrast, some activities can give rise to external benefits, or positive externalities.

There are costs as well as benefits to reducing pollution, so the optimal quantity of pollution isn’t zero. Instead, the socially optimal quantity of pollution is the quantity at which the marginal social cost of pollution is equal to the marginal social benefit of pollution.

Left to itself, a market economy will typically generate an inefficiently high level of pollution because polluters have no incentive to take into account the costs they impose on others.

According to the Coase theorem, the private sector can sometimes resolve externalities on its own: if transaction costs aren’t too high, individuals can reach a deal to internalize the externality. When transaction costs are too high, government intervention may be warranted.

16-1

Question 16.1

Wastewater runoff from large poultry farms adversely affects their neighbors. Explain the following:

The nature of the external cost imposed

The external cost is the pollution caused by the wastewater runof f, an uncompensated cost imposed by the poultry farms on their neighbors.The outcome in the absence of government intervention or a private deal

Since poultry farmers do not take the external cost of their actions into account when making decisions about how much wastewater to generate, they will create more runoff than is socially optimal in the absence of government intervention or a private deal. They will produce runoff up to the point at which the marginal social benefit of an additional unit of runoff is zero; however, their neighbors experience a high, positive level of marginal social cost of runoff from this output level. So the quantity of wastewater runoff is inefficient: reducing runoff by one unit would reduce total social benefit by less than it would reduce total social cost.The socially optimal outcome

At the socially optimal quantity of wastewater runoff, the marginal social benefit is equal to the marginal social cost. This quantity is lower than the quantity of wastewater runoff that would be created in the absence of government intervention or a private deal.

Question 16.2

According to Yasmin, any student who borrows a book from the university library and fails to return it on time imposes a negative externality on other students. She claims that rather than charging a modest fine for late returns, the library should charge a huge fine so that borrowers will never return a book late. Is Yasmin’s economic reasoning correct?

Yasmin’s reasoning is not correct: allowing some late returns of books is likely to be socially optimal. Although you impose a marginal social cost on others every day that you are late in returning a book, there is some positive marginal social benefit to you of returning a book late—for example, you get a longer period to use it in working on a term paper.The socially optimal number of days that a book is returned late is the number at which the marginal social benefit equals the marginal social cost. A fine so stiff that it prevents any late returns is likely to result in a situation in which people return books although the marginal social benefit of keeping them another day is greater than the marginal social cost—an inefficient outcome. In that case, allowing an overdue patron another day would increase total social benefit more than it would increase total social cost. So charging a moderate fine that reduces the number of days that books are returned late to the socially optimal number of days is appropriate.

Solutions appear at back of book.