Policies Toward Pollution

Before 1970, there were no rules governing the amount of sulfur dioxide that coal-

In 1970, Congress adopted the Clean Air Act, which set rules forcing power plants to reduce their emissions. And it worked—

In this section we’ll look at the policies governments use to deal with pollution and at how economic analysis has been used to improve those policies.

Environmental Standards

The most serious external costs in the modern world are surely those associated with actions that damage the environment—

Environmental standards are rules that protect the environment by specifying actions by producers and consumers.

How does a country protect its environment? At present the main policy tools are environmental standards, rules that protect the environment by specifying actions by producers and consumers. A familiar example is the law that requires almost all vehicles to have catalytic converters, which reduce the emission of chemicals that can cause smog and lead to health problems. Other rules require communities to treat their sewage or factories to avoid or limit certain kinds of pollution. And as we just saw in the Economics in Action, environmental standards were put in place in 2014, compelling new coal-

Environmental standards came into widespread use in the 1960s and 1970s, and they have had considerable success in reducing pollution. For example, since the United States passed the Clean Air Act in 1970, overall emission of pollutants into the air has fallen by more than a third, even though the population has grown by a third and the size of the economy has more than doubled. Even in Los Angeles, still famous for its smog, the air has improved dramatically: in 1976 ozone levels in the South Coast Air Basin exceeded federal standards on 194 days; in 2013, on only 5 days.

Emissions Taxes

An emissions tax is a tax that depends on the amount of pollution a firm produces.

Another way to deal with pollution directly is to charge polluters an emissions tax. Emissions taxes are taxes that depend on the amount of pollution a firm emits. As we learned in Chapter 7, a tax imposed on an activity will reduce the level of that activity. Looking again at Figure 16-2, we can find the amount of tax on emissions that moves the market to the socially optiimal point. At QOPT, the socially optimal quantity of pollution, the marginal social benefit and marginal social cost of an additional unit of pollution is equal at $200. But in the absence of government intervention, polluters will push pollution up to the quantity QMKI, at which marginal social benefit is zero.

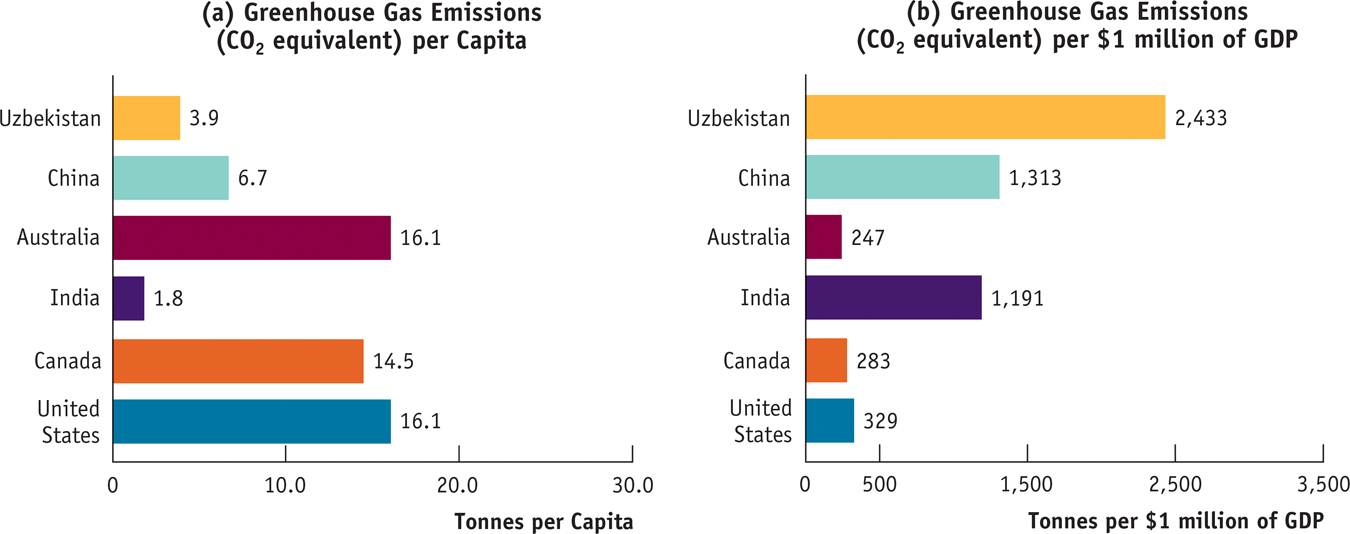

| Economic Growth and Greenhouse Gases in Six Countries |

At first glance, a comparison of the per capita greenhouse gas emissions of various countries, shown in panel (a) of this graph, suggests that Australia, Canada, and the United States are the worst offenders. The average American is responsible for 16.1 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions (measured in CO2 equivalents)—the pollution that causes climate change—

Such a conclusion, however, ignores an important factor in determining the level of a country’s greenhouse gas emissions: its gross domestic product, or GDP—

A more meaningful way to compare pollution across countries is to measure emissions per $1 million of a country’s GDP, as shown in panel (b). On this basis, the United States, Canada, and Australia are now “green” countries, but China, India, and Uzbekistan are not. What explains the reversal once GDP is accounted for? The answer: both economics and government behavior.

First, there is the issue of economics. Countries that are poor and have begun to industrialize, such as China and Uzbekistan, often view money spent to reduce pollution as better spent on other things. From their perspective, they are still too poor to afford as clean an environment as wealthy advanced countries. They claim that to impose a wealthy country’s environmental standards on them would jeopardize their economic growth.

Second, there is the issue of government behavior—

Sources: Global Carbon Atlas; IMF—

It’s now easy to see how an emissions tax can solve the problem. If polluters are required to pay a tax of $200 per unit of pollution, they now face a marginal cost of $200 per unit and have an incentive to reduce their emissions to QOPT, the socially optimal quantity. This illustrates a general result: an emissions tax equal to the marginal social cost at the socially optimal quantity of pollution induces polluters to internalize the externality—

Taxes designed to reduce external costs are known as Pigouvian taxes.

The term emissions tax may convey the misleading impression that taxes are a solution to only one kind of external cost, pollution. In fact, taxes can be used to discourage any activity that generates negative externalities, such as driving (which inflicts environmental damage greater than the cost of producing gasoline) or smoking (which inflicts health costs on society far greater than the cost of making a cigarette). In general, taxes designed to reduce external costs are known as Pigouvian taxes, after the economist A. C. Pigou, who emphasized their usefulness in his classic 1920 book, The Economics of Welfare. In our example, the optimal Pigouvian tax is $200. As you can see from Figure 16-2, this corresponds to the marginal social cost of pollution at the optimal output quantity QOPT.

Are there any problems with emissions taxes? The main concern is that in practice government officials usually aren’t sure how high the tax should be set. If they set it too low, there won’t be sufficient reduction in pollution; if they set it too high, emissions will be reduced by more than is efficient. This uncertainty around the optimal level of the emissions tax can’t be eliminated, but the nature of the risks can be changed by using an alternative policy, issuing tradable emissions permits.

Tradable Emissions Permits

Tradable emissions permits are licenses to emit limited quantities of pollutants that can be bought and sold by polluters.

Tradable emissions permits are licenses to emit limited quantities of pollutants that can be bought and sold by polluters. Tradable emissions permits work in practice much like the tradable quotas discussed in a Chapter 5 Economics in Action in which regulators created a system of tradable licenses to fish for crabs. The tradable licenses resulted in an efficient way to allocate the right to fish as boat-

Here’s why this system works in the case of pollution. Firms that pollute typically have different costs of reducing pollution—

In the end, those with the lowest cost of reducing pollution will reduce their pollution the most, while those with the highest cost of reducing pollution will reduce their pollution the least. The total effect is to allocate pollution reduction efficiently—

Just like emissions taxes, tradable emissions permits provide polluters with an incentive to take the marginal social cost of pollution into account. To see why, suppose that the market price of a permit to emit one unit of pollution is $200. Every polluter now has an incentive to limit its emissions to the point where its marginal benefit of one unit of pollution is $200. Why?

If the marginal benefit of one more unit of pollution is greater than $200 then it is cheaper to pollute more than to pollute less. In that case the polluter will buy a permit and emit another unit. And if the marginal benefit of one more unit of pollution is less than $200, then it is cheaper to reduce pollution than to pollute more. In that scenario the polluter will reduce pollution rather than buy the $200 permit.

From this example we can see how an emissions permit leads to the same outcome as an emissions tax when they are the same amount: a polluter who pays $200 for the right to emit one unit faces the same incentives as a polluter who faces an emissions tax of $200 per unit. And it’s equally true for polluters that have received more permits from regulators than they plan to use: by not emitting one unit of pollution, a polluter frees up a permit that it can sell for $200. In other words, the opportunity cost of a unit of pollution to this firm is $200, regardless of whether it is used.

Recall that when using emissions taxes to arrive at the optimal level of pollution, the problem arises of finding the right amount of the tax: if the tax is too low, too much pollution is emitted; if the tax is too high, too little pollution is emitted (in other words, too many resources are spent reducing pollution). A similar problem with tradable emissions permits is getting the quantity of permits right, which is much like the flip-

Because it is difficult to determine the optimal quantity of pollution, regulators can find themselves either issuing too many permits, so that there is insufficient pollution reduction, or issuing too few, so that there is too much pollution reduction.

In the case of sulfur dioxide pollution, the U.S. government first relied on environmental standards, but then turned to a system of tradable emissions permits. Currently the largest emissions permit trading system is the European Union system for controlling emissions of carbon dioxide.

Comparing Environmental Policies with an Example

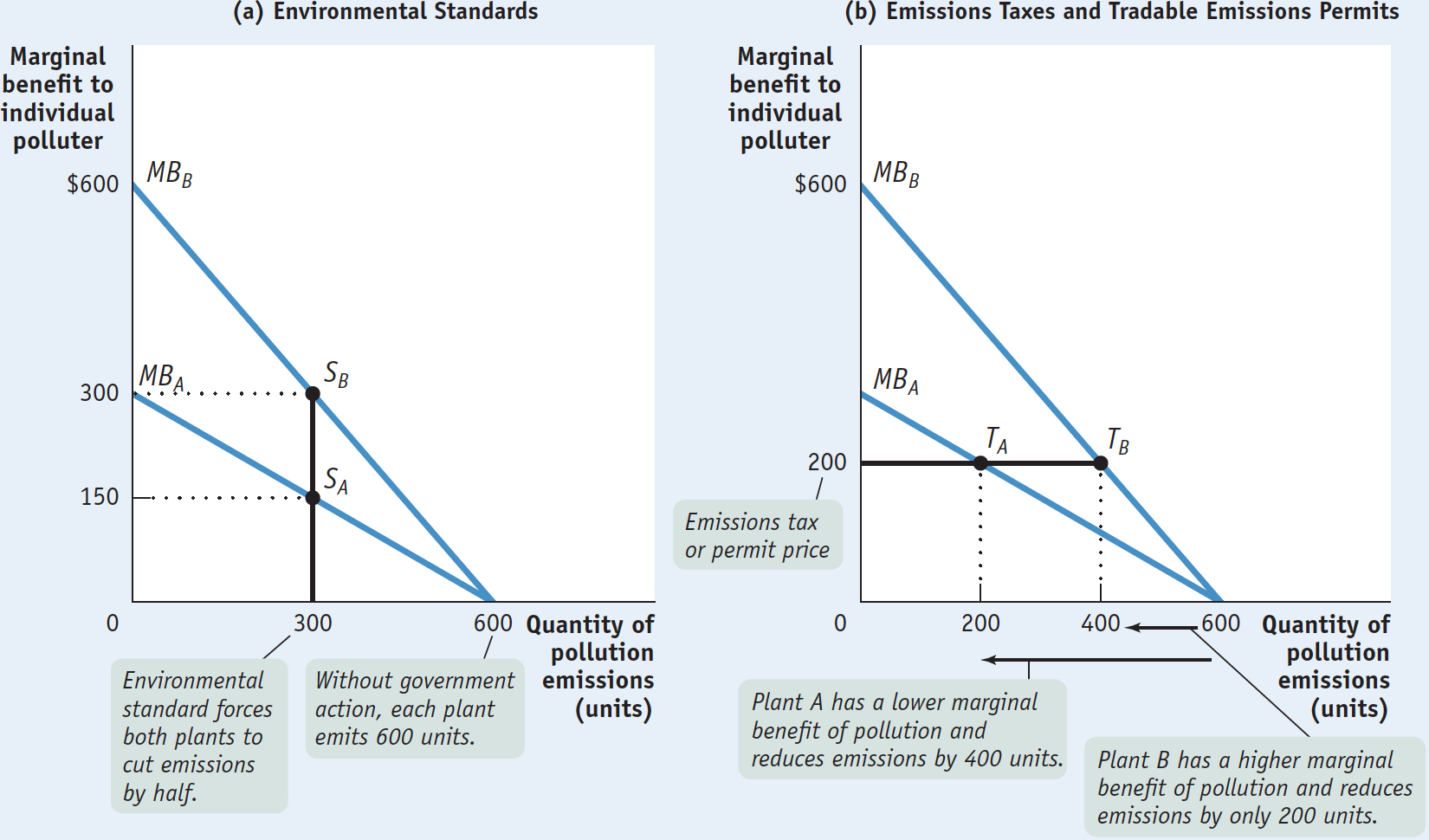

Figure 16-3 shows a hypothetical industry consisting of only two plants, plant A and plant B. We’ll assume that plant A uses newer technology, giving it a lower cost of pollution reduction, while plant B uses older technology and has a higher cost of pollution reduction. Reflecting this difference, plant A’s marginal benefit of pollution curve, MBA, lies below plant B’s marginal benefit of pollution curve, MBB. Because it is more costly for plant B to reduce its pollution at any output quantity, an additional unit of pollution is worth more to plant B than to plant A.

16-3

Comparing Environmental Policies

In the absence of government action, we know that polluters will pollute until the marginal social benefit of a unit of pollution is equal to zero. As a result, without government intervention each plant will pollute until its own marginal benefit of pollution is equal to zero. This corresponds to an emissions quantity of 600 units for each plant—

Now suppose that regulators decide that the overall pollution from this industry should be cut in half, from 1,200 units to 600 units. Panel (a) of Figure 16-3 shows this might be achieved with an environmental standard that requires each plant to cut its emissions in half, from 600 to 300 units. The standard has the desired effect of reducing overall emissions from 1,200 to 600 units but accomplishes it inefficiently.

As you can see from panel (a), the environmental standard leads plant A to produce at point SA, where its marginal benefit of pollution is $150, but plant B produces at point SB, where its marginal benefit of pollution is twice as high, $300.

This difference in marginal benefits between the two plants tells us that the same quantity of pollution can be achieved at lower total cost by allowing plant B to pollute more than 300 units but inducing plant A to pollute less. In fact, the efficient way to reduce pollution is to ensure that at the industry-

We can see from panel (b) how an emissions tax achieves exactly that result. Suppose both plant A and plant B pay an emissions tax of $200 per unit, so that the marginal cost of an additional unit of emissions to each plant is now $200 rather than zero. As a result, plant A produces at TA and plant B produces at TB. So plant A reduces its pollution more than it would under an inflexible environmental standard, cutting its emissions from 600 to 200 units; meanwhile, plant B reduces its pollution less, going from 600 to 400 units.

In the end, total pollution—

Panel (b) also illustrates why a system of tradable emissions permits also achieves an efficient allocation of pollution among the two plants. Assume that in the market for permits, the market price of a permit is $200 and each plant has 300 permits to start the system. Plant B, with the higher cost of pollution reduction, will buy 200 permits from Plant A, enough to allow it to emit 400 units. Correspondingly, Plant A, with the lower cost, will sell 200 of its permits to Plant B and emit only 200 units. Provided that the market price of a permit is the same as the optimal emissions tax, the two systems arrive at the same outcome.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Cap and Trade

Cap and Trade

The tradable emissions permit systems for both acid rain in the United States and greenhouse gases in the European Union are examples of cap and trade systems: the government sets a cap (a maximum amount of pollutant that can be emitted), issues tradable emissions permits, and enforces a yearly rule that a polluter must hold a number of permits equal to the amount of pollutant emitted. The goal is to set the cap low enough to generate environmental benefits, while giving polluters flexibility in meeting environmental standards and motivating them to adopt new technologies that will lower the cost of reducing pollution.

In 1994 the United States began a cap and trade system for the sulfur dioxide emissions that cause acid rain by issuing permits to power plants based on their historical consumption of coal. Thanks to the system, air pollutants in the United States decreased by more than 40% from 1990 to 2008, and by 2012 acid rain levels dropped to approximately 70% of their 1980 levels. Economists who have analyzed the sulfur dioxide cap and trade system point to another reason for its success: it would have been a lot more expensive—

The EU cap and trade scheme, begun in 2005 and covering all 28 member nations of the European Union, is the world’s only mandatory trading system for greenhouse gases. Other countries, like Australia and New Zealand, have adopted less comprehensive schemes.

According to the World Bank, the worldwide market for greenhouse gases—

Yet cap and trade systems are not silver bullets for the world’s pollution problems. Although they are appropriate for pollution that’s geographically dispersed, like sulfur dioxide and greenhouse gases, they don’t work for pollution that’s localized, like groundwater contamination. And there must be vigilant monitoring of compliance for the system to work. Finally, the amount of total reduction in pollution depends on the level of the cap, a critical issue illustrated by the troubles of the EU cap and trade scheme.

EU regulators, under industry pressure, allowed too many permits to be handed out when the system was created. By the spring of 2013 the price of a permit for a ton of greenhouse gas had fallen to 2.75 euros (about $3.70), less than a tenth of what experts believe is necessary to induce companies to switch to cleaner fuels like natural gas. The price of a permit was too low to alter polluters’ incentives and, not surprisingly, coal use in Europe boomed in 2012. Alarmed European Union legislators voted in the summer of 2013 to reduce the number of permits issued in future years in the hope of increasing the current price of a permit. There is evidence the reduction in permits has already altered polluters’ incentives. As of mid-

Quick Review

Governments often limit pollution with environmental standards. Generally, such standards are an inefficient way to reduce pollution because they are inflexible.

Environmental goals can be achieved efficiently in two ways: emissions taxes and tradable emissions permits. These methods are efficient because they are flexible, allocating more pollution reduction to those who can do it more cheaply. They also motivate polluters to adopt new pollution-

reducing technology. An emissions tax is a form of Pigouvian tax. The optimal Pigouvian tax is equal to the marginal social cost of pollution at the socially optimal quantity of pollution.

16-2

Question 16.3

Some opponents of tradable emissions permits object to them on the grounds that polluters that sell their permits benefit monetarily from their contribution to polluting the environment. Assess this argument.

This is a misguided argument. Allowing polluters to sell emissions permits makes polluters face a cost of polluting: the opportunity cost of the permit. If a polluter chooses not to reduce its emissions, it cannot sell its emissions permits. As a result, it forgoes the opportunity of making money from the sale of the permits. So despite the fact that the polluter receives a monetary benefit from selling the permits, the scheme has the desired effect: to make polluters internalize the externality of their actions.Question 16.4

Explain the following.

Why an emissions tax smaller than or greater than the marginal social cost at QOPT leads to a smaller total surplus compared to the total surplus generated if the emissions tax had been set optimally

If the emissions tax is smaller than the marginal social cost at QOPT, a polluter will face a marginal cost of polluting (equal to the amount of the tax) that is less than the marginal social cost at the socially optimal quantity of pollution. Since a polluter will produce emissions up to the point where the marginal social benefit is equal to its marginal cost, the resulting amount of pollution will be larger than the socially optimal quantity. As a result, there is inefficiency: if the amount of pollution is larger than the socially optimal quantity, the marginal social cost exceeds the marginal social benefit, and society could gain from a reduction in emissions levels.

If the emissions tax is greater than the marginal social cost at QOPT, a polluter will face a marginal cost of polluting (equal to the amount of the tax) that is greater than the marginal social cost at the socially optimal quantity of pollution. This will lead the polluter to reduce emissions below the socially optimal quantity. This also is inefficient: whenever the marginal social benefit is greater than the marginal social cost, society could benefit from an increase in emissions levels.

Why a system of tradable emissions permits that sets the total quantity of allowable pollution higher or lower than QOPT leads to a smaller total surplus compared to the total surplus generated if the number of permits had been set optimally.

If the total amount of allowable pollution is set too high, the supply of emissions permits will be high and so the equilibrium price at which permits trade will be low. That is, polluters will face a marginal cost of polluting (the price of a permit) that is “too low”—lower than the marginal social cost at the socially optimal quantity of pollution. As a result, pollution will be greater than the socially optimal quantity. This is inefficient and lowers total surplus.

If the total level of allowable pollution is set too low, the supply of emissions permits will be low and so the equilibrium price at which permits trade will be high. That is, polluters will face a marginal cost of polluting (the price of a permit) that is “too high”—higher than the marginal social cost at the socially optimal quantity of pollution. As a result, pollution will be lower than the socially optimal quantity. This also is inefficient and lowers total surplus.

Solutions appear at back of book.