Artificially Scarce Goods

An artificially scarce good is excludable but nonrival in consumption.

An artificially scarce good is a good that is excludable but nonrival in consumption. As we’ve already seen, on-

As we’ve already seen, markets will supply artificially scarce goods: because they are excludable, the producers can charge people for consuming them.

But artificially scarce goods are nonrival in consumption, which means that the marginal cost of an individual’s consumption is zero. So the price that the supplier of an artificially scarce good charges exceeds marginal cost. Because the efficient price is equal to the marginal cost of zero, the good is “artificially scarce,” and consumption of the good is inefficiently low. However, unless the producer can somehow earn revenue for producing and selling the good, he or she will be unwilling to produce at all—

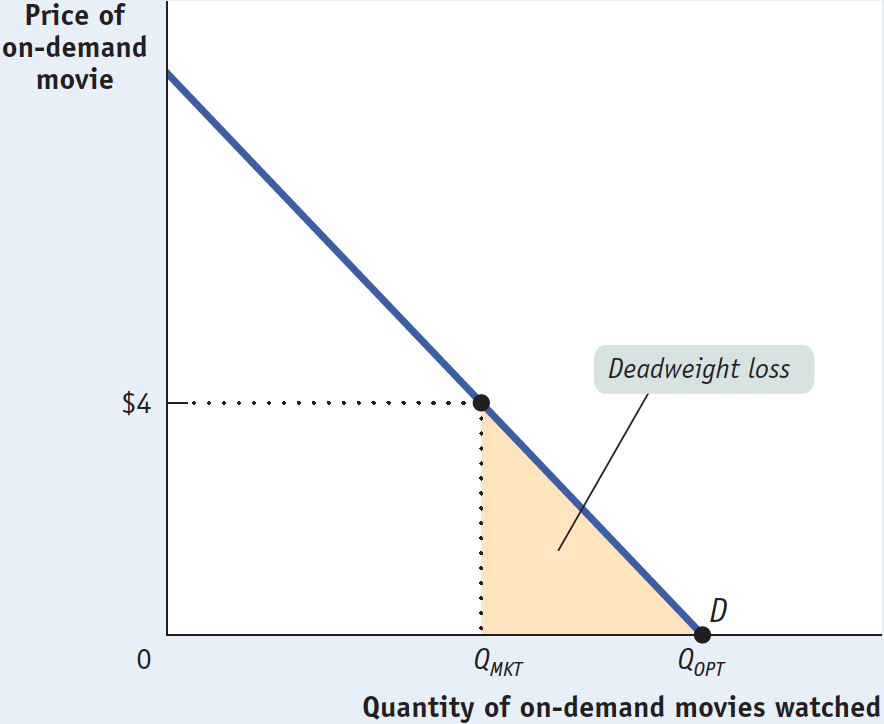

Figure 17-4 illustrates the loss in total surplus caused by artificial scarcity. The demand curve shows the quantity of on-

17-4

An Artificially Scarce Good

Does this look familiar? Like the problems that arise with public goods and common resources, the problem created by artificially scarce goods is similar to the problem of natural monopoly. A natural monopoly, you will recall, is an industry in which average total cost is above marginal cost for the relevant output range. In order to be willing to produce output, the producer must charge a price at least as high as average total cost—

ECONOMICS in Action: Blacked-Out Games

Blacked-

It was the first weekend of 2014 and the Green Bay Packers were hosting the San Francisco 49ers in the wild-

What the message wouldn’t say, but that Packer’s fans understood quite well, was that this blackout was at the insistence of the team’s owners, who didn’t want people who might have paid for tickets staying home and watching the game on TV instead. Often games that fail to sell out their stadium tickets are blacked out in local broadcast markets.

So the good in question—

Sometimes, though, accommodations are made in specific situations. In this case, enough Packers’ fans rallied in sub-

Quick Review

An artificially scarce good is excludable but nonrival in consumption.

Because the good is nonrival in consumption, the efficient price to consumers is zero. However, because it is excludable, sellers charge a positive price, which leads to inefficiently low consumption.

The problems of artificially scarce goods are similar to those posed by a natural monopoly.

17-4

Question 17.6

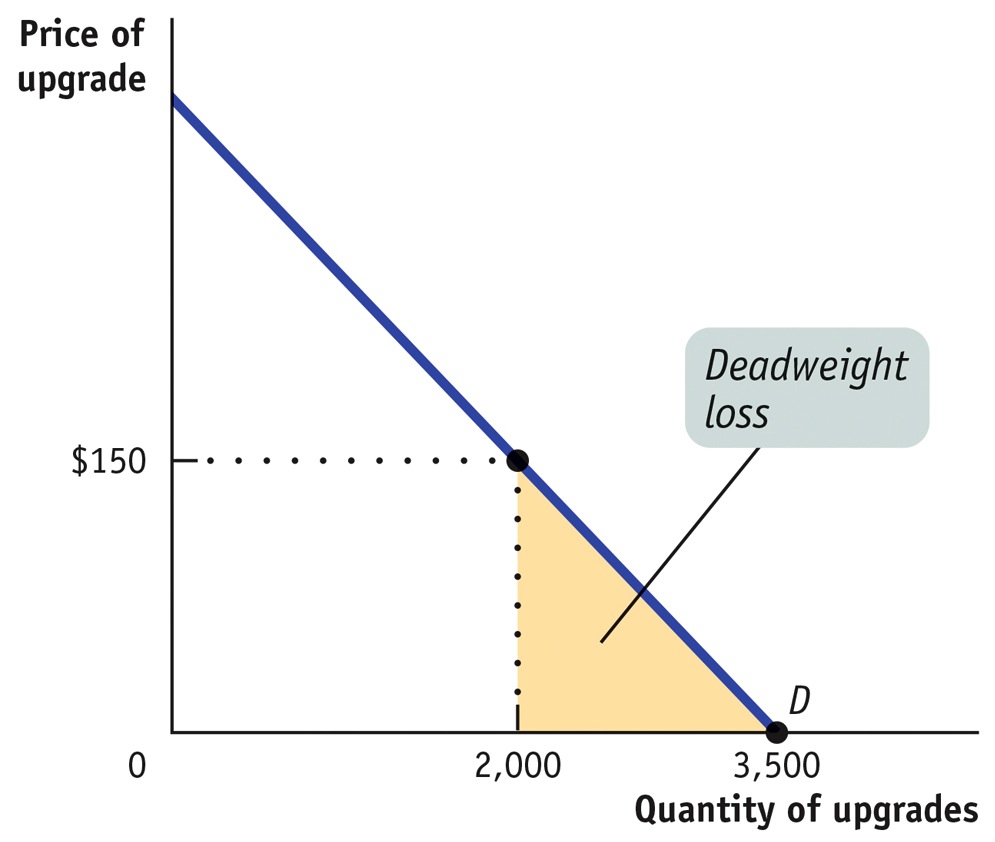

Xena is a software program produced by Xenoid. Each year Xenoid produces an upgrade that costs $300,000 to produce. It costs nothing to allow customers to download it from the company’s website. The demand schedule for the upgrade is shown in the accompanying table.

Price of upgrade

Quantity of upgrades demanded

$180

1,700

150

2,000

120

2,300

90

2,600

0

3,500

What is the efficient price to a consumer of this upgrade? Explain your answer.

The efficient price to a consumer is $0, since the marginal cost of allowing a consumer to download it is $0.

What is the lowest price at which Xenoid is willing to produce and sell the upgrade? Draw the demand curve and show the loss of total surplus that occurs when Xenoid charges this price compared to the efficient price.

Xenoid will not produce the software unless it can charge a price that allows it at least to make back the $300,000 cost of producing it. So the lowest price at which Xenoid is willing to produce it is $150. At this price, it makes a total revenue of $150 × 2,000 = $300,000; at any lower price, Xenoid will not cover its cost. The shaded area in the accompanying diagram shows the deadweight loss when Xenoid charges a price of $150.

Solutions appear at back of book.

Mauricedale Game Ranch and Hunting Endangered Animals to Save Them

John Hume’s Mauricedale ranch occupies 16,000 square miles in the hot, scrubby grasslands of South Africa. There Hume raises endangered species, such as rhinos, and nonendangered species, such as Cape buffalo, antelopes, hippos, giraffes, zebras, and ostriches. From revenues of around $2.5 million per year, the ranch earns a small profit, with 20% of the revenues coming from trophy hunting and 80% from selling live animals.

Although he entered this business to earn a profit, Hume sees himself as a conservator of these animals and this land. And he is convinced that to protect rhinos, some amount of legalized hunting of them is necessary. The story of one of Hume’s male rhinos, named “65,” illustrates his point. Hume and his staff knew that 65 was a problem: too old to breed, he was belligerent enough to kill younger male rhinos. He was part of what wildlife conservationists call the “surplus male problem,” a male whose presence inhibits the growth of the herd.

Eventually, Hume obtained permission for the hunting of 65 from CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) that regulates the trade and legalized hunting of endangered species. A wealthy hunter paid Hume $150,000, and the troublesome 65 was quickly dispatched.

Conservationist ranchers like Hume, who advocate regulated hunting of wildlife, point to the experience of Kenya to buttress their case. In 1977, Kenya banned the trophy hunting or ranching of wildlife. Since then, Kenya has lost 60% to 70% of its large wildlife through poaching or conversion of habitat to agriculture. Its herd of black rhinos, once numbered at 20,000, now stands at about 540, surviving only in protected areas. In contrast, since regulated hunting of the less endangered white buffalo began in South Africa in 1968, its numbers have risen from 1,800 to 19,400.

Many conservationists now agree that the key to recovery for a number of endangered species is legalized hunting on well-

However, legalized hunting is a very controversial policy, strongly opposed by some wildlife advocates. Because establishing a ranch like Mauricedale requires a huge capital investment, many are concerned that smaller, fly-

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 17.7

Using the concepts you learned in this chapter, explain the economic incentives behind the huge losses in Kenyan wildlife.

Using the concepts you learned in this chapter, explain the economic incentives behind the huge losses in Kenyan wildlife.Question 17.8

Compare the economic incentives facing John Hume with those facing a Kenyan rancher.

Compare the economic incentives facing John Hume with those facing a Kenyan rancher.Question 17.9

What regulations should be imposed on a rancher who sells opportunities to trophy hunt? Relate these to the concepts in the chapter.

What regulations should be imposed on a rancher who sells opportunities to trophy hunt? Relate these to the concepts in the chapter.