The Economics of Health Care

18-5

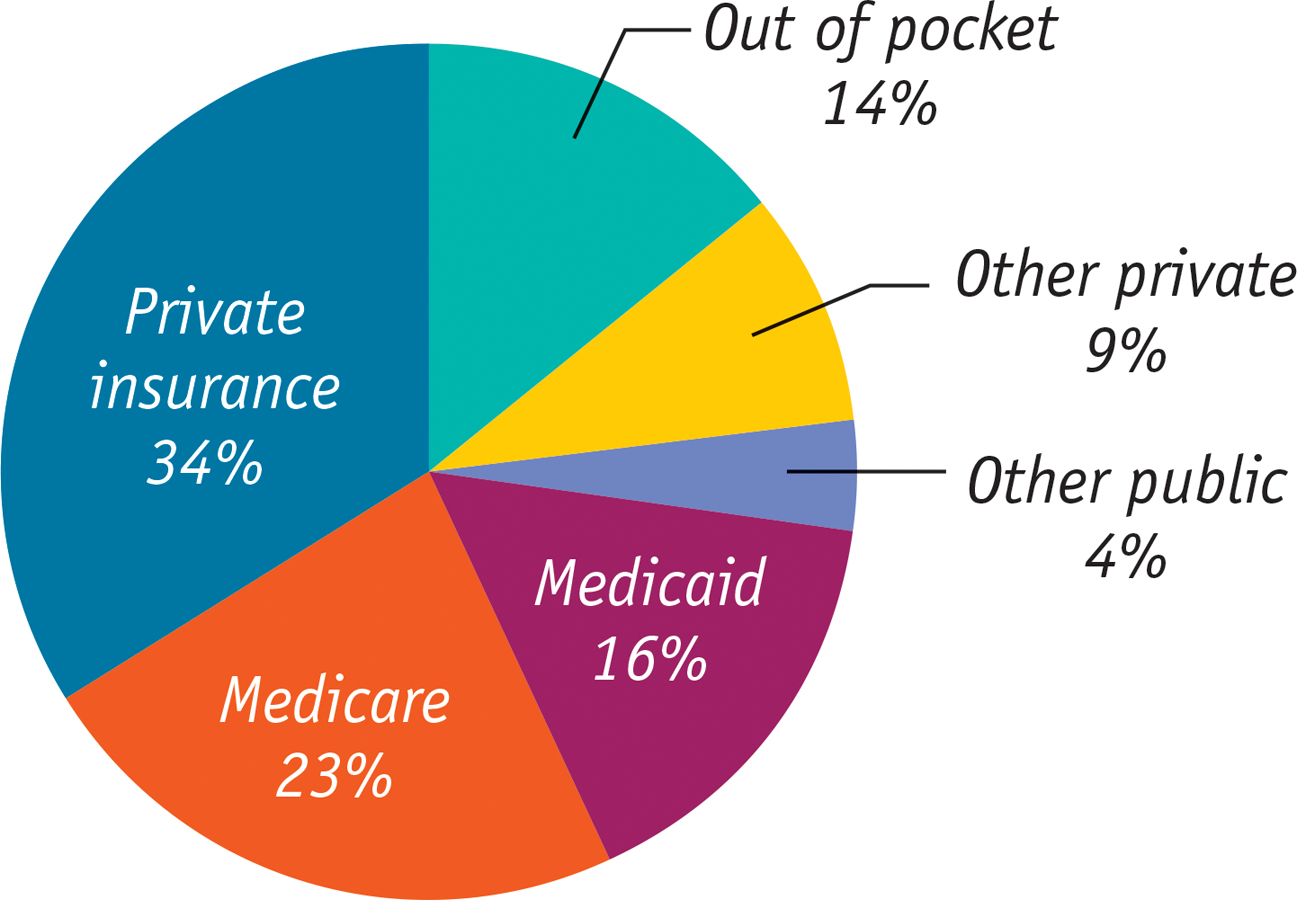

Who Paid for U.S. Health Care in 2012?

A large part of the welfare state, in both the United States and other wealthy countries, is devoted to paying for health care. In most wealthy countries, the government pays between 70% and 80% of all medical costs. The private sector plays a larger role in the U.S. health care system. Yet even in America, as of 2013 the government pays almost half of all health care costs; furthermore, it indirectly subsidizes private health insurance through the federal tax code.

Figure 18-5 shows who paid for U.S. health care in 2012. Only 14% of health care consumption spending (that is, all spending on health care except investment in health care buildings and facilities) was expenses “out of pocket”—that is, paid directly by individuals. Most health care spending, 77%, was paid for by some kind of insurance. Of this 77%, considerably less than half was private insurance; the rest was some kind of government insurance, mainly Medicare and Medicaid. To understand why, we need to examine the special economics of health care.

The Need for Health Insurance

In 2012, U.S. personal health care expenses were $8,915 per person—

Is it possible to predict who will have high medical costs? To a limited extent, yes: there are broad patterns to illness. For example, the elderly are more likely to need expensive surgery and/or drugs than the young. But the fact is that anyone can suddenly find himself or herself needing very expensive medical treatment, costing many thousands of dollars in a very short time—

Under private health insurance, each member of a large pool of individuals pays a fixed amount annually to a private company that agrees to pay most of the medical expenses of the pool’s members.

Private Health Insurance Market economies have an answer to this problem: health insurance. Under private health insurance, each member of a large pool of individuals agrees to pay a fixed amount annually (called a premium) into a common fund that is managed by a private company, which then pays most of the medical expenses of the pool’s members. Although members must pay fees even in years in which they don’t have large medical expenses, they benefit from the reduction in risk: if they do turn out to have high medical costs, the pool will take care of those expenses.

There are, however, inherent problems with the market for private health insurance. These problems arise from the fact that medical expenses, although basically unpredictable, aren’t completely unpredictable. That is, people often have some idea whether or not they are likely to face large medical bills over the next few years. This creates a serious problem for private health insurance companies.

Suppose that an insurance company offers a “one-

If all potential customers had an equal risk of incurring high medical expenses for the year, this might be a workable business proposition. In reality, however, people often have very different risks of facing high medical expenses—

As a result, some healthy people are likely to take their chances and go without insurance. This would make the insurance company’s average customer less healthy than the average American. This raises the medical bills the company will have to pay and raises the company’s costs per customer. That is, the insurance company would face a problem called adverse selection, which is discussed in detail in Chapter 20. Because of adverse selection, a company that offers health insurance to everyone at a price reflecting average medical costs of the general population, and that gives people the freedom to decline coverage, would find itself losing a lot of money.

The insurance company could respond by charging more—

This description of the problems with health insurance might lead you to believe that private health insurance can’t work. In fact, however, most Americans are covered by private health insurance. Insurance companies are able, to some extent, to overcome the problem of adverse selection two ways: by carefully screening people who apply for coverage and through employment-

Employment-

A California Death Spiral

Early in 2006, 116,000 workers at more than 6,000 California small businesses received health coverage from PacAdvantage, a “purchasing pool” that offered employees at member businesses a choice of insurance plans. The idea behind PacAdvantage, which was founded in 1992, was that by banding together, employees of small businesses could get better deals on health insurance.

But only a few months later, in August 2006, PacAdvantage announced that it was closing up shop because it could no longer find insurance companies willing to offer plans to its members.

What happened? It was the adverse selection death spiral. PacAdvantage offered the same policies to everyone, regardless of their prior health history. But employees didn’t have to get insurance from PacAdvantage—

There’s another reason employment-

In spite of this subsidy, however, many working Americans don’t receive employment-

Government Health Insurance

Table 18-6 shows the breakdown of health insurance coverage across the U.S. population in 2013. A majority of Americans, nearly 170 million people, received health insurance through their employers. The majority of those who didn’t have private insurance were covered by two government programs, Medicare and Medicaid. (The numbers don’t add up because some people have more than one form of coverage. For example, many recipients of Medicare also have supplemental coverage either through Medicaid or private policies.)

18-6

Number of Americans Covered by Health Insurance, 2013 (millions)

|

Covered by private health insurance |

201.1 |

|---|---|

|

Employment- |

169.0 |

|

Direct purchase |

34.5 |

|

Covered by government |

107.6 |

|

Medicaid |

54.1 |

|

Medicare |

49.0 |

|

Military health care |

14.1 |

|

Not covered |

42.0 |

|

Source: U.S. Census Bureau. |

|

Medicare, financed by payroll taxes, is available to all Americans 65 and older, regardless of their income and wealth. It began in 1966 as a program to cover the cost of hospitalization but has since been expanded to cover a number of other medical expenses. You can get an idea of how much difference Medicare makes to the finances of elderly Americans by comparing the median income per person of Americans 65 and older—

At the beginning of 2006, there was a major expansion of Medicare to cover the cost of prescription drugs. At the time Medicare was created, drugs played a relatively minor role in medicine and were rarely a major expense for patients. Today, however, many health problems, especially among the elderly, are treated with expensive drugs that must be taken for years on end, placing severe strains on some people’s finances. As a result, a new Medicare program, known as Part D, was created to help pay these expenses.

Unlike Medicare, Medicaid is a means-

Nearly 14 million Americans receive health insurance as a consequence of military service. Unlike Medicare and Medicaid, which pay medical bills but don’t deliver health care directly, the Veterans Health Administration, which has more than 8 million clients, runs hospitals and clinics around the country.

The U.S. health care system, then, offers a mix of private insurance, mainly from employers, and public insurance of various forms. Most Americans have health insurance either from private insurance companies or through various forms of government insurance. Yet in 2012, before the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, almost 48 million, or 15.4% of the population, had no health insurance at all. What accounted for the high number of uninsured? And why was it such a severe problem that it spurred the passage of the Affordable Care Act?

The Problem of the Uninsured Before the Affordable Care Act

Before the passage of the ACA, the Kaiser Family Foundation, an independent nonpartisan group that studies health care issues, offered a succinct summary of who was uninsured in America: “The uninsured are largely low-

Low-

It’s important to realize that lack of insurance was not simply due to poverty. Before the ACA, most of the uninsured had incomes above the poverty threshold, and 35% had incomes more than twice the poverty threshold. We should also note that some of the uninsured were people who could afford insurance but preferred to save money and take their chances.

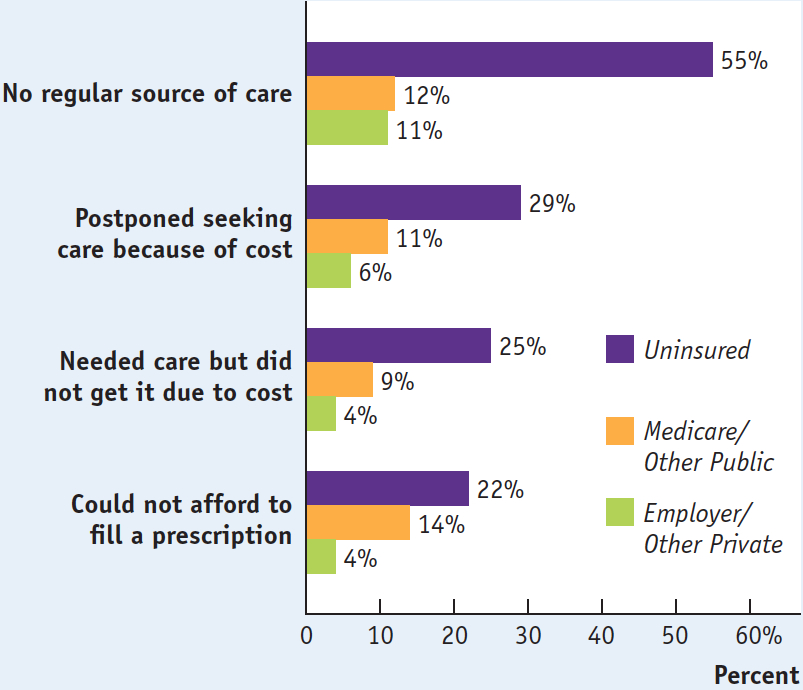

Like poverty, lack of health insurance has severe consequences, both medical and financial. On the medical side, the uninsured frequently have limited access to health care. Figure 18-6 summarizes some of the common problems associated with access to care, all of which are much worse for the uninsured than for the insured. On the monetary side, those who are uninsured often face serious financial problems when illness strikes. In many cases those without insurance are five times more likely than those with health insurance to be contacted by collection agencies, deplete their savings paying for medical expenses, or not pay altogether.

18-6

Barriers to Receiving Health Care, 2012

Health Care in Other Countries

Health care is one area in which the United States is very different from other wealthy countries, including both European nations and Canada. In fact, we’re distinctive in three ways. First, we rely much more on private health insurance than any other wealthy country. Second, we spend much more on health care per person. Third, we were the only wealthy nation in which large numbers of people lacked health insurance until the ACA started to change that.

Table 18-7 compares the United States with three other wealthy countries: Canada, France, and Britain. The United States is the only one of the four countries that relies on private health insurance to cover most people; as a result, it’s the only one in which private spending on health care is (slightly) larger than public spending on health care. (This will not change under the ACA as most health insurance will continue to be provided by private insurers.)

18-7

Health Care Systems in Advanced Countries, 2012

|

|

Government share of health care spending |

Health care spending per capita (US$, purchasing power parity) |

Life expectancy (total population at birth, years) |

Infant mortality (deaths per 1,000 live births) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

United States |

47.6% |

$8,745 |

78.7 |

6.0 |

|

Canada |

70.1 |

4,603 |

81.2 |

4.7 |

|

France |

77.4 |

4,288 |

82.6 |

3.4 |

|

Britain |

84.0 |

3,289 |

81.5 |

4.1 |

|

Source: OECD. |

||||

A single-

Canada has a single-

Canada, Britain, and France provide health insurance to all their citizens; the United States does not. Yet all three spend much less on health care per person than we do. Many Americans assume this must mean that foreign health care is inferior in quality. But many health care experts disagree with the claim that the health care systems of other wealthy countries deliver poor-

Surveys of patients seem to suggest that there are no significant differences in the quality of care received by patients in Canada, Europe, and the United States. And as Table 18-7 shows, the United States does considerably worse than other advanced countries in terms of basic measures such as life expectancy and infant mortality, although our poor performance on these measures may have causes other than the quality of medical care—

So why does the United States spend so much more on health care than other wealthy countries? Some of the disparity is the result of higher doctors’ salaries, but most studies suggest that this is a secondary factor. One possibility is that Americans are getting better care than their counterparts abroad, but in ways that don’t show up in either surveys of patient experiences or statistics on health performance.

However, the most likely explanation is that the U.S. system suffers from serious inefficiencies that other countries manage to avoid. Critics of the U.S. system emphasize the fact that our system’s reliance on private insurance companies makes it highly fragmented, as individual insurance companies each expend resources on overhead and on such activities as marketing and trying to identify and weed out high-

By contrast, Medicare spends only 3% of its funds on operating costs, leaving 97% to spend on health care. A study by the McKinsey Global Institute found that the United States spends almost six times as much per person on health care administration as other wealthy countries. Americans also pay higher prices for prescription drugs because, in other countries, government agencies bargain with pharmaceutical companies to get lower drug prices.

The Affordable Care Act

However one rates the past performance of the U.S. health care system, by 2009 it was clearly in trouble, on two fronts.

First, a growing number of working-

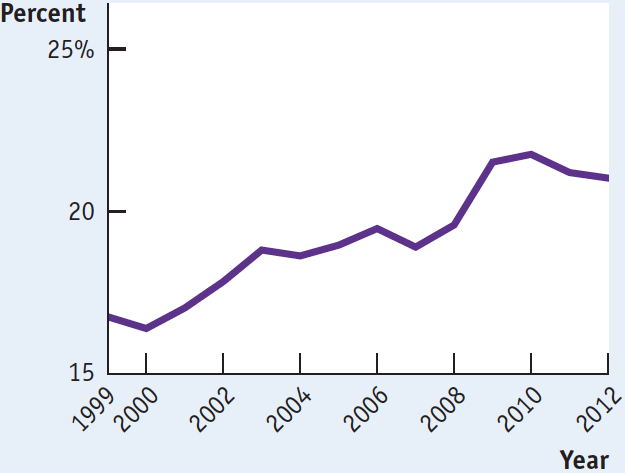

18-7

Uninsured Working-

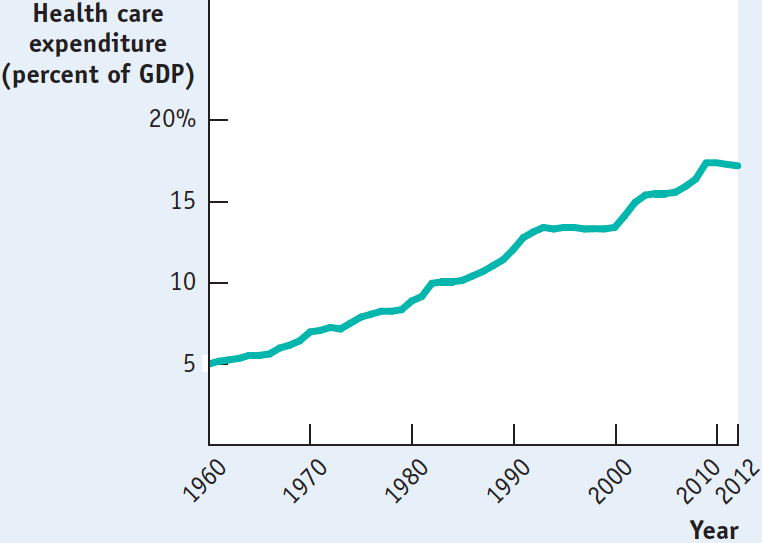

Lying behind the growing number of uninsured, in turn, were sharply rising premiums for health insurance, reflecting rapid growth in overall health care costs. Figure 18-8 shows overall U.S. spending on health care as a percentage of GDP, a measure of the nation’s total income, since the 1960s. As you can see, health spending has tripled as a share of income since 1965; this increase in spending explains why health insurance has become more expensive. Similar trends can be observed in other countries.

18-8

Rising Health Care Costs, 1960-

Why was health spending rising? The consensus of health experts is that it’s a result of medical progress. As medical science progresses, conditions that could not be treated in the past become treatable—

The combination of a rising number of uninsured and rising costs led to many calls for health care reform in the United States. And so in 2010 Congress passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) which took full effect in 2014. It was the largest expansion of the American welfare state since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. It had two major objectives: covering the uninsured and cost control. Let’s look at each in turn.

Covering the Uninsured On the coverage side, the ACA closely follows a model that has been successfully used in Massachusetts since 2006 (introduced under Republican governor at the time, Mitt Romney). To understand the logic of both the Massachusetts plan and the ACA, consider the problem facing one major category of uninsured Americans: the many people who seek coverage in the individual insurance market but are turned down because they have preexisting medical conditions, which insurance companies fear could lead to large future expenses. (Insurance companies were known to deny coverage for even minor ailments, like allergies or a rash you had in college.) How could insurance be made available to such people?

One answer would be regulations requiring that insurance companies offer the same policies to everyone, regardless of medical history—

To make community rating work, it’s necessary to supplement it with other policies. Both the Massachusetts reform and the ACA add two key features. First is the requirement that everyone purchase health insurance—

It’s important to realize that this system is like a three-

Will this arrangement, once fully implemented, succeed in covering more or less everyone? The Massachusetts precedent is encouraging on that front: by 2012, more than 96% of the state’s residents had health insurance and virtually all children were covered. Since the ACA is very similar in structure, it ought to produce similar results.

Cost Control But will the ACA control costs? In itself, the expansion of coverage will raise health care spending, although not by as much as you might think. The uninsured are by and large relatively young, and the young have relatively low health care costs. (The elderly are already covered by Medicare.) The question is whether the reform can succeed in “bending the curve”—reducing the rate of growth of health costs over time.

The ACA’s promise to control costs starts from the premise that the U.S. medical system, as currently constituted, has skewed incentives that waste resources. Because most care is paid for by insurance, neither doctors nor patients have an incentive to worry about costs. In fact, because health care providers are generally paid for each procedure they perform, there’s a financial incentive to provide additional care—

The bill attempts to correct these skewed incentives in a variety of ways, from stricter oversight of reimbursements, to linking payments to a procedure’s medical value, to paying health care providers for improved health outcomes rather than the number of procedures, and by limiting the tax deductibility of employment-

The ACA’s launch As you might gather, the ACA sets up an insurance system considerably more complex than other government programs like Medicare and Medicaid, which simply provide insurance directly. The ACA sets up special online marketplaces, the “exchanges,” in which insurance companies offer policies from which individuals must choose. To figure out how much these policies really cost, it’s necessary to calculate the subsidy you receive, which depends on your income as well as the premium. Making all of that work is a difficult programming problem. And sure enough, when healthcare.gov, the federally run online exchange, started up in October 2013, the system crashed repeatedly. For the next two months few people managed to sign up.

This was, however, a problem with the software, not the fundamental structure of the law, and by the beginning of 2014 it was largely solved. There was a huge surge of people signing up as the deadline for 2014 coverage approached, and by the time that deadline arrived more than 8 million people had signed up via the exchanges, while millions more had either purchased directly from insurers or been covered by an expansion of Medicaid.

How many of those signing up were newly insured? At first there were warnings that many of the policies being bought through the exchanges might simply be replacing existing coverage. By the summer of 2014, however, multiple independent surveys showed a sharp drop in the percentage of respondents without insurance. At this point it seems likely that the ACA will, indeed, manage to cover many though not all uninsured Americans. Whether it will also succeed in reducing the rate of cost growth remains to be seen, although by 2014 there were early signs that the rate of growth of health care costs was indeed falling.

ECONOMICS in Action: What Medicaid Does

What Medicaid Does

Do social insurance programs actually help their beneficiaries? The answer isn’t always as obvious as you might think. Take the example of Medicaid, which provides health insurance to low-

Testing such assertions is tricky. You can’t just compare people who are on Medicaid with people who aren’t, since the program’s beneficiaries differ in many ways from those who aren’t on the program. And we don’t normally get to do controlled experiments in which otherwise comparable groups receive different government benefits.

Once in a while, however, events provide the equivalent of a controlled experiment—

So what were the results? It turned out that Medicaid made a big difference. Those on Medicaid received

60% more mammograms

35% more outpatient care

30% more hospital care

20% more cholesterol checks

Medicaid recipients were also

70% more likely to have a consistent source of care

55% more likely to see the same doctor over time

45% more likely to have had a Pap test within the last year (for women)

40% less likely to need to borrow money or skip payment on other bills because of medical expenses

25% percent more likely to report themselves in “good” or “excellent” health

15% more likely to use prescription drugs

15% more likely to have had a blood test for high blood sugar or diabetes

10% percent less likely to screen positive for depression

In short, Medicaid led to major improvements in access to medical care and the well-

Quick Review

Health insurance satisfies an important need because expensive medical treatment is unaffordable for most families. Private health insurance has an inherent problem: the adverse selection death spiral. Screening by insurance companies reduces the problem, and employment-

based health insurance, the way most Americans are covered, avoids it altogether. The majority of Americans not covered by private insurance are covered by Medicare, which is a non-

means- tested single- payer system for those over 65, and Medicaid, which is means-tested. Compared to other wealthy countries, the United States depends more heavily on private health insurance, has higher health care spending per person, higher administrative costs, and higher drug prices, but without clear evidence of better health outcomes.

Health care costs everywhere are increasing rapidly due to medical progress. The 2010 ACA legislation was designed to address the large and growing share of American uninsured and to reduce the rate of growth of health care spending.

18-3

Question 18.7

If you are enrolled in a four-

year degree program, it is likely that you are required to enroll in a health insurance program run by your school unless you can show proof of existing insurance coverage.. Explain how you and your parents benefit from this health insurance program even though, given your age, it is unlikely that you will need expensive medical treatment.

The program benefits you and your parents because the pool of all college students contains a representative mix of healthy and less healthy people, rather than a selected group of people who want insurance because they expect to pay high medical bills. In that respect, this insurance is like employment-based health insurance. Because no student can opt out, the school can offer health insurance based on the health care costs of its average student. If each student had to buy his or her own health insurance, some students would not be able to obtain any insurance and many would pay more than they do to the school’s insurance program.Explain how your school’s health insurance program avoids the adverse selection death spiral.

Since all students are required to enroll in its health insurance program, even the healthiest students cannot leave the program in an effort to obtain cheaper insurance tailored specifically to healthy people. If this were to happen, the school’s insurance program would be left with an adverse selection of less healthy students and so would have to raise premiums, beginning the adverse selection death spiral. But since no student can leave the insurance program, the school’s program can continue to base its premiums on the average student’s probability of requiring health care, avoiding the adverse selection death spiral.

Question 18.8

According to its critics, what accounts for the higher costs of the U.S. health care system compared to those of other wealthy countries?

According to critics, part of the reason the U.S. health care system is so much more expensive than those of other countries is its fragmented nature. Since each of the many insurance companies has significant administrative (overhead) costs—in part because each insurance company incurs marketing costs and exerts significant effort in weeding out high-risk insureds—the system tends to be more expensive than one in which there is only a single medical insurer. Another part of the explanation is that U.S. medical care includes many more expensive treatments than found in other wealthy countries, pays higher physician salaries, and has higher drug prices.

Solutions appear at back of book.