The Debate over the Welfare State

The goals of the welfare state seem laudable: to help the poor, to protect against severe economic hardship and to ensure access to essential health care. But good intentions don’t always make for good policy. There is an intense debate about how large the welfare state should be, a debate that partly reflects differences in philosophy but also reflects concern about the possibly counterproductive effects on incentives of welfare state programs. Disputes about the size of the welfare state are also one of the defining issues of modern American politics.

Problems with the Welfare State

There are two different arguments against the welfare state. One, which we described earlier in this chapter, is based on philosophical concerns about the proper role of government. As we learned, some political theorists believe that redistributing income is not a legitimate role of government. Rather, they believe that government’s role should be limited to maintaining the rule of law, providing public goods, and managing externalities.

The more conventional argument against the welfare state involves the trade-

But this must be balanced against the efficiency costs of high marginal tax rates. Consider an extremely progressive tax system that imposes a marginal rate of 90% on very high incomes. The problem is that such a high marginal rate reduces the incentive to increase a family’s income by working hard or making risky investments. As a result, an extremely progressive tax system tends to make society as a whole poorer, which could hurt even those the system was intended to benefit. That’s why even economists who strongly favor progressive taxation don’t support a return to the extremely progressive system that prevailed in the 1950s, when the top U.S. marginal income tax rate was more than 90%. So, the design of the tax system involves a trade-

A similar trade-

Table 18-8 shows “social expenditure,” a measure that roughly corresponds to total welfare state spending, as a percentage of GDP in the United States, Britain, and France. It also compares this with an estimate of the marginal tax rate faced by an average single wage-

18-8

Social Expenditure and Marginal Tax Rates

|

|

Social expenditure in 2012 (percent of GDP) |

Marginal tax rate in 2009 |

|---|---|---|

|

United States |

19.4% |

43.6% |

|

Britain |

23.9 |

40.3 |

|

France |

32.1 |

59.8 |

|

Source: OECD. Marginal tax rate is defined as a percentage of total labor costs. |

||

One way to hold down the costs of the welfare state is to means-

This feature of means-

Even so, the combined effects of the major means-

The Politics of the Welfare State

In 1791, in the early phase of the French Revolution, French citizens convened a congress, the Legislative Assembly, in which representatives were seated according to social class: the upper classes, who pretty much liked the way things were, sat on the right; commoners, who wanted big changes, sat on the left. Ever since, political commentators refer to politicians as being on the “right” (more conservative) or on the “left” (more liberal).

But what do modern politicians on the left and right disagree about? In the modern United States, they mainly disagree about the appropriate size of the welfare state. The debate over the Affordable Care Act was a case in point, with the vote on the bill breaking down entirely according to party lines—

You might think that saying that political debate is really about just one thing—

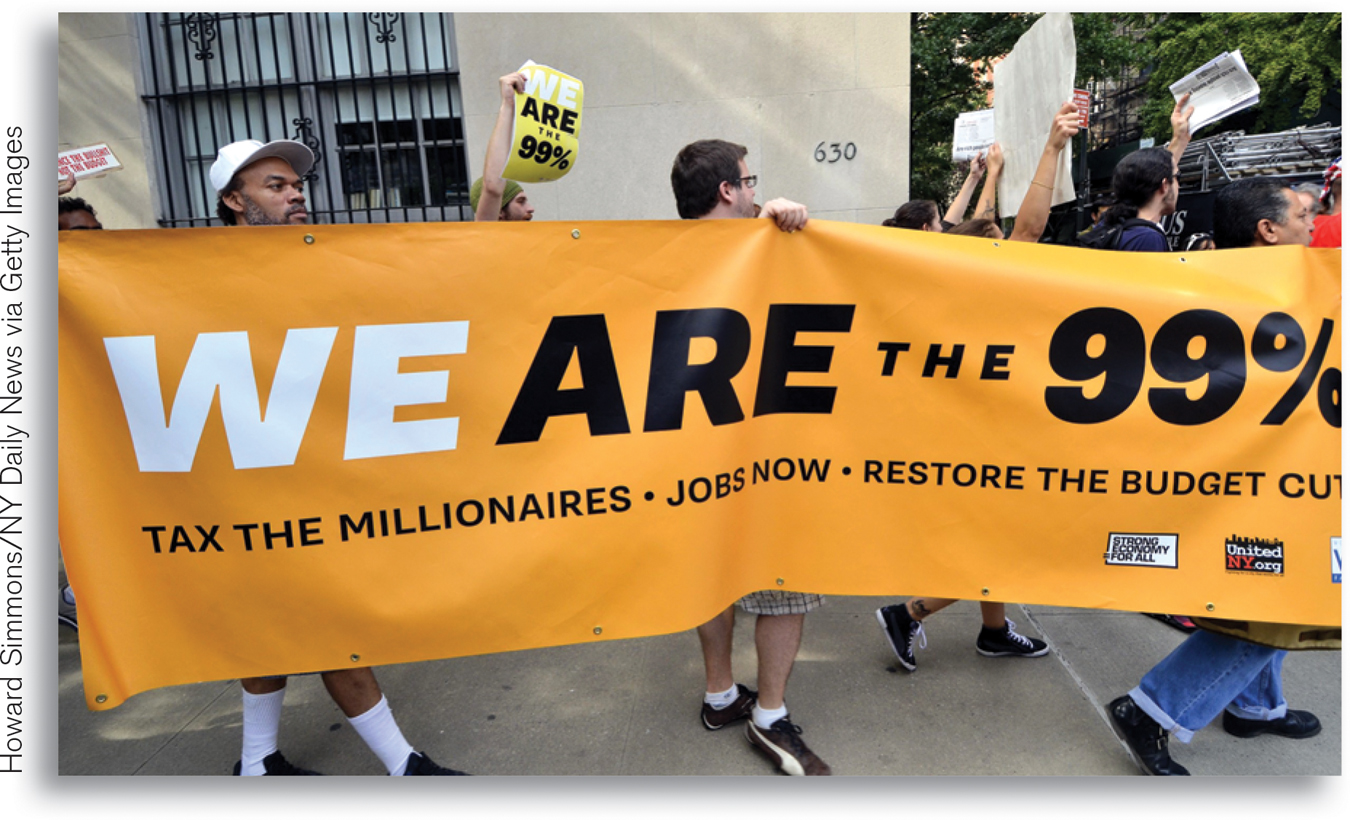

“We Are the 99%!”

In the fall of 2011, Zuccotti Park, a small open space in Manhattan’s financial district, was taken over by protestors, part of a movement known as “Occupy Wall Street.” The protestors had a number of grievances, but the most pressing were their complaints about Wall Street and its perceived contribution to growing inequality in the United States. “We are the 99 percent!” became the movement’s favored slogan, a reference to the large increase in share of income going to the top 1% of the American population. Wall Street, they charged, contributed to growing inequality by paying its bankers huge salaries and bonuses, while engaging in overly risky behavior that led to the housing boom and bust of 2007-

Those who found it unreasonable pointed to the contributions that Wall Street, and the American finance industry in general, have made to the U.S. economy. Compared to other countries, the United States is a leader in financial services and innovation, generating billions annually in revenues, and attracting trillions of dollars of investment from abroad. High salaries on Wall Street, they contend, are simply the rewards for skill and hard work in the competitive market for talent on Wall Street.

What is incontrovertible, however, are the data that show that incomes in the finance industry have contributed to growing inequality in the United States. This is especially clear when you look not at the top percentile of the income distribution, but at an even smaller group, the top 0.1%—those with a median annual income of $5.6 million.

Although financial industry people are a minority (18%) within this income elite—

The same studies that show a strong left-

Can economic analysis help resolve this political conflict? Only up to a point.

Some of the political controversy over the welfare state involves differences in opinion about the trade-

To an important extent, however, differences of opinion on the welfare state reflect differences in values and philosophy. And those are differences economics can’t resolve.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: French Family Values

French Family Values

The United States has the smallest welfare state of any major advanced economy. France has one of the largest. As we’ve already described, France has much higher social spending than America as a percentage of total national income, and French citizens face much higher tax rates than Americans. One argument against a large welfare state is that it has negative effects on efficiency. Does French experience support this argument?

On the face of it, the answer would seem to be a clear yes. French GDP per capita—

A closer examination, however, reveals that the story is more complicated than that. The low level of employment in France is entirely the result of low rates of employment among the young and the old; about 80% of French residents of prime working age, 25–

Shorter working hours also reflect factors besides tax rates. French law requires employers to offer at least a month of vacation, but most U.S. workers get less than two weeks off. Here, too, the French will tell you that their policy is better than ours because it helps families spend time together.

The aspect of French policy even the French agree is a big problem is that their retirement system allows workers to collect generous pensions even if they retire very early. As a result, only 45% of French residents between the ages of 55 and 64 are employed, compared with more than 60% of Americans. The cost of supporting all those early retirees is a major burden on the French welfare state—

Quick Review

Intense debate on the size of the welfare state centers on philosophy and on equity-

versus- efficiency concerns. The high marginal tax rates needed to finance an extensive welfare state can reduce the incentive to work. Holding down the cost of the welfare state by means- testing can also cause inefficiency through notches that create high effective marginal tax rates for benefit recipients. Politics is often depicted as an opposition between left and right; in the modern United States, that division mainly involves disagreement over the appropriate size of the welfare state.

18-4

Question 18.9

Explain how each of the following policies creates a disincentive to work or undertake a risky investment.

A high sales tax on consumer items

Recall one of the principles from Chapter 1: one person’s spending is another person’s income. A high sales tax on consumer items is the same as a high marginal tax rate on income. As a result, the incentive to earn income by working or by investing in risky projects is reduced, since the payoff, after taxes, is lower.

The complete loss of a housing subsidy when yearly income rises above $25,000

If you lose a housing subsidy as soon as your income rises above $25,000, your incentive to earn more than $25,000 is reduced. If you earn exactly $25,000, you obtain the housing subsidy; however, as soon as you earn $25,001, you lose the entire subsidy, making you worse off than if you had not earned the additional dollar. The complete withdrawal of the housing subsidy as income rises above $25,000 is what economists refer to as a notch.

Question 18.10

Over the past 40 years, has the polarization in Congress increased, decreased, or stayed the same?

Over the past 40 years, polarization in Congress has increased. Forty years ago, some Republicans were to the left of some Democrats. Today, the rightmost Democrats appear to be to the left of the leftmost Republicans.

Solutions appear at back of book.

Welfare State Entrepreneurs

“Wiggo Dalmo is a classic entrepreneurial type: the Working Class Kid Made Good.” So began a profile in the January 2011 issue of Inc. magazine. Dalmo began as an industrial mechanic who worked for a large company, repairing mining equipment. Eventually, however, he decided to strike out on his own and start his own business. Momek, the company he founded, eventually grew into a $44 million, 150-

You can read stories like this all the time in U.S. business publications. What was unusual about this particular article is that Dalmo and his company aren’t American, they’re Norwegian—

Why? After all, the financial rewards for being a successful entrepreneur are more limited in a country like Norway, with its high taxes, than they are in the United States, with its lower taxes. But there are other considerations. For example, at least until the Affordable Care Act kicked in in January 2014, an American thinking of leaving a large company to start a new business needed to worry about whether he or she would be able to get health insurance, whereas a Norwegian in the same position was assured of health care regardless of employment. And the downside of failure is larger in the U.S. system, which offers minimal aid to the unemployed.

18-9

The Top 10 Entrepreneurial Countries, 2014

|

Rank |

Country |

|---|---|

|

1 |

United States |

|

2 |

Australia |

|

3 |

Sweden |

|

4 |

Denmark |

|

5 |

Switzerland |

|

6 |

Taiwan |

|

7 |

Finland |

|

8 |

Netherlands |

|

9 |

United Kingdom |

|

10 |

Singapore |

|

Source: The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index 2014, by Zoltan Acs, Laszlo Szerb and Erkko Autio. |

|

Still, is Wiggo Dalmo an exceptional case? Table 18-9 shows the nations with the highest level of entrepreneurial activity, according to a study financed by the U.S. Small Business Administration, which tried to quantify the level of entrepreneurial activity in different nations. The United States is at the top of the list, but so are several Scandinavian countries which have very high levels of taxation and extensive social insurance. (Norway, for example, is number 14.)

The moral is that when comparing how business friendly different welfare state systems really are, you have to think a bit past the obvious question of the level of taxes.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 18.11

Why does Norway have to have higher taxes overall than the United States?

Why does Norway have to have higher taxes overall than the United States?Question 18.12

This case suggests that government-

paid health care helps entrepreneurs. How does this relate to the arguments for social insurance in the text? This case suggests that government-paid health care helps entrepreneurs. How does this relate to the arguments for social insurance in the text? Question 18.13

How would the incentives of people like Wiggo Dalmo be affected if Norwegian health care was means-

tested instead of available to all? How would the incentives of people like Wiggo Dalmo be affected if Norwegian health care was means-tested instead of available to all?