Is the Marginal Productivity Theory of Income Distribution Really True?

Although the marginal productivity theory of income distribution is a well-

First, in the real world we see large disparities in income between factors of production that, in the eyes of some observers, should receive the same payment. Perhaps the most conspicuous examples in the United States are the large differences in the average wages between women and men and among various racial and ethnic groups. Do these wage differences really reflect differences in marginal productivity, or is something else going on?

Second, many people wrongly believe that the marginal productivity theory of income distribution gives a moral justification for the distribution of income, implying that the existing distribution is fair and appropriate. This misconception sometimes leads other people, who believe that the current distribution of income is unfair, to reject marginal productivity theory.

To address these controversies, we’ll start by looking at income disparities across gender and ethnic groups. Then we’ll ask what factors might account for these disparities and whether these explanations are consistent with the marginal productivity theory of income distribution.

Wage Disparities in Practice

Wage rates in the United States cover a very wide range. In 2013, hundreds of thousands of workers received the legal federal minimum of $7.25 per hour. At the other extreme, the chief executives of several companies were paid more than $100 million, which works out to $20,000 per hour even if they worked 100-

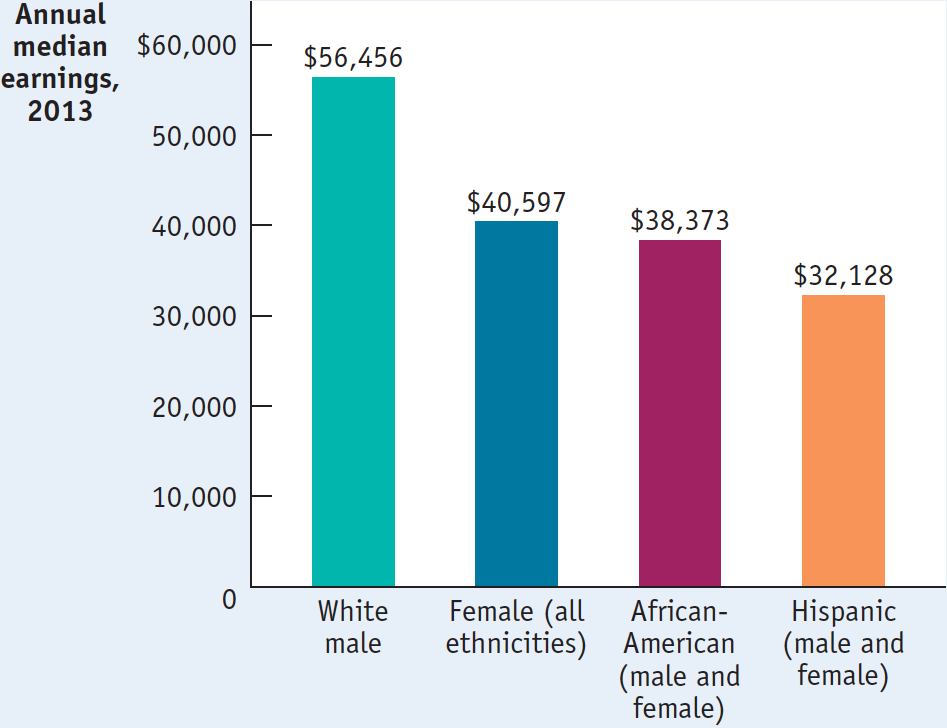

A particular source of concern is the existence of systematic wage differences across gender and ethnicity. Figure 19-8 compares annual median earnings in 2013 of workers age 25 or older classified by gender and ethnicity. As a group, White males had the highest earnings. Other data show that women (averaging across all ethnicities) earned only about 72% as much; African-

19-8

Median Earnings by Gender and Ethnicity, 2013

We are a nation founded on the belief that all men are created equal—

Marginal Productivity and Wage Inequality

A large part of the observed inequality in wages can be explained by considerations that are consistent with the marginal productivity theory of income distribution. In particular, there are three well-

Compensating differentials are wage differences across jobs that reflect the fact that some jobs are less pleasant than others.

First is the existence of compensating differentials: across different types of jobs, wages are often higher or lower depending on how attractive or unattractive the job is. Workers with unpleasant or dangerous jobs demand a higher wage in comparison to workers with jobs that require the same skill and effort but lack the unpleasant or dangerous qualities. For example, truckers who haul hazardous loads are paid more than truckers who haul non-

A second reason for wage inequality that is clearly consistent with marginal productivity theory is differences in talent. People differ in their abilities: a higher-

A third and very important reason for wage differences is differences in the quantity of human capital. Recall that human capital—

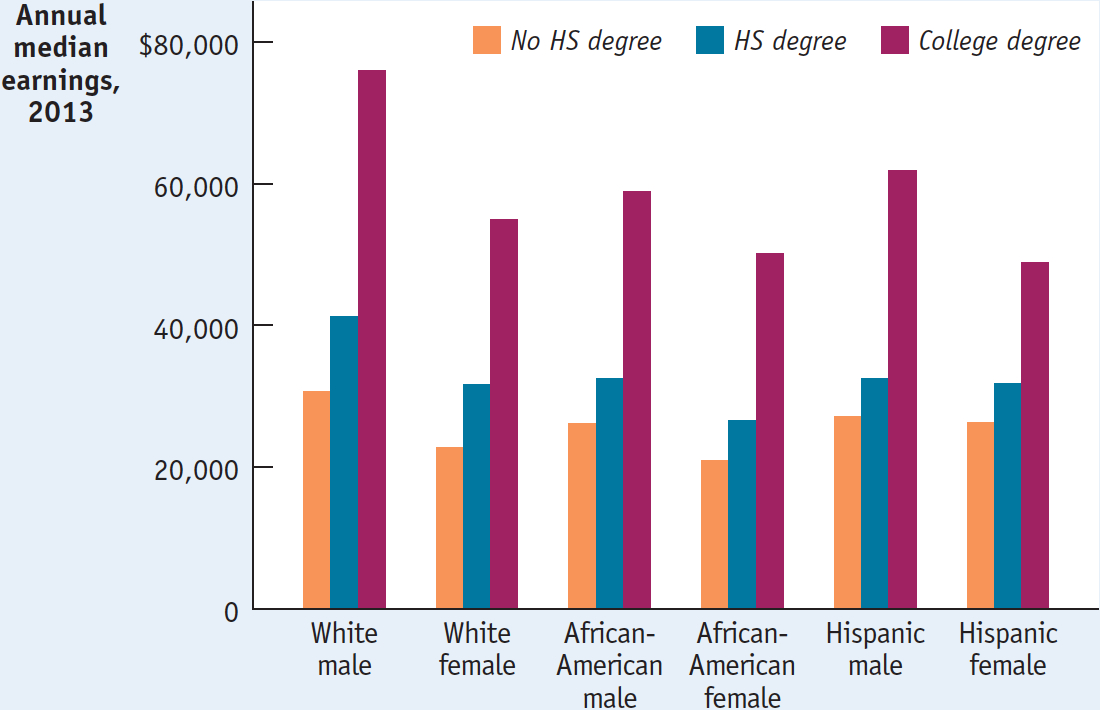

The most direct way to see the effect of human capital on wages is to look at the relationship between educational levels and earnings. Figure 19-9 shows earnings differentials by gender, ethnicity, and three educational levels for people age 25 or older in 2013. As you can see, regardless of gender or ethnicity, higher education is associated with higher median earnings. For example, in 2013 White females with 9 to 12 years of schooling but without a high school diploma had median earnings 28% less than those with a high school diploma and 65% less than those with a college degree—

19-9

Earnings Differentials by Education, Gender, and Ethnicity, 2013

Because even now men typically have had more years of education than women and Whites more years than non-

It’s important to realize that formal education is not the only source of human capital; on-

human capital (women tend to have lower levels of it)

choice of occupation (women tend to choose occupations such as nursing and teaching in which they earn less)

career interruptions (women move in and out of labor force more frequently)

part-

time status (women are more likely to work part- time instead of full- time) overtime status (women are less likely to work overtime)

For example, in a U.S. Department of Labor study using recent census data, the gender-

But it’s also important to emphasize that earnings differences arising from these factors are not necessarily “fair.” When women do most of the work caring for children, they will inevitably have more career interruptions or need to work part-

Still, many observers think that actual wage differentials cannot be entirely explained by compensating differentials, differences in talent, differences in human capital, or differences in job status. They believe that market power, efficiency wages, and discrimination also play an important role. We will examine these forces next.

Market Power

The marginal productivity theory of income distribution is based on the assumption that factor markets are perfectly competitive. In such markets we can expect workers to be paid the equilibrium value of their marginal product, regardless of who they are. But how valid is this assumption?

We studied markets that are not perfectly competitive in Chapters 13, 14, and 15; now let’s touch briefly on the ways in which labor markets may deviate from the competitive assumption.

Unions are organizations of workers that try to raise wages and improve working conditions for their members by bargaining collectively with employers.

One undoubted source of differences in wages between otherwise similar workers is the role of unions—organizations that try to raise wages and improve working conditions for their members. Labor unions, when they are successful, replace one-

How much does collective action, either by workers or by employers, affect wages in the modern United States? Several decades ago, when around 30% of American workers were union members, unions probably had a significant upward effect on wages. Today, however, most economists think unions exert a fairly minor influence.

In 2013, less than 7% of the employees of private businesses were represented by unions. Just as workers can sometimes organize to extract higher wages than they would otherwise receive, employers can sometimes organize to pay lower wages than would result from competition. For example, health care workers—

Efficiency Wages

A second source of wage inequality is the phenomenon of efficiency wages—a type of incentive scheme used by employers to motivate workers to work hard and to reduce worker turnover. Suppose a worker performs a job that is extremely important but that the employer can observe how well the job is being performed only at infrequent intervals—

So a worker who happens to be observed performing poorly and is therefore fired is now worse off for having to accept a lower-

According to the efficiency-

The efficiency-

As a result, two workers with exactly the same profile—

Efficiency wages are a response to a type of market failure that arises when some employees are able to hide the fact that they don’t always perform as well as they should. As a result, employers use nonequilibrium wages to motivate their employees, leading to an inefficient outcome.

Discrimination

It is a real and ugly fact that throughout history there has been discrimination against workers who are considered to be of the wrong race, ethnicity, gender, or other characteristics. How does this fit into our economic models?

The main insight economic analysis offers is that discrimination is not a natural consequence of market competition. On the contrary, market forces tend to work against discrimination. To see why, consider the incentives that would exist if social convention dictated that women be paid, say, 30% less than men with equivalent qualifications and experience. A company whose management was itself unbiased would then be able to reduce its costs by hiring women rather than men—

But if market competition works against discrimination, how is it that so much discrimination has taken place? The answer is twofold. First, when labor markets don’t work well, employers may have the ability to discriminate without hurting their profits. For example, market interferences (such as unions or minimum-

How Labor Works the German Way

Germany is home to some of the finest manufacturing firms in the world. From the automotive sector to beer brewing, and from home appliances to chemical engineering and pharmaceuticals, German products are considered among the highest quality available. And unlike in the United States, blue-

Enshrined in the German constitution, works councils exist in every factory to encourage management and employees to work together on issues like work conditions, productivity, and wages, with the goal of discouraging costly conflict. Workers are given seats in supervisory or management organizations such as a company’s board of directors. This collaborative environment, in turn, supports higher levels of unionization within German manufacturing. As a result, German unions are more successful at raising the wages of their members.

But what allows German manufacturing to compete successfully while paying higher wages? One explanation is the German apprentice system. For example, in 2012, the average hourly wage of a German autoworker was $58.82 compared to $45.34 (at the high end) for an American autoworker, and $14.50 (at the low end) in newly opened automotive plants in the United States. Promoted and accredited by the German government, apprenticeship programs provide hands-

So integral is the apprenticeship system to the success of German manufacturing that German companies have been replicating it at their plants in the United States. In South Carolina, where BMW and Tognum, a German engine maker, have recently located, apprenticeship programs have been created in partnership with local and state governments to assure that young workers are trained in the skills that the companies need. And, needless to say, the apprentices welcome such training and the well-

In research published in the American Economic Review, two economists, Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan, documented discrimination in hiring by sending fictitious résumés to prospective employers on a random basis. Applicants with “White-

Second, discrimination has sometimes been institutionalized in government policy. This institutionalization of discrimination has made it easier to maintain it against market pressure, and historically it is the form that discrimination has typically taken. For example, at one time in the United States, African-

Although market competition tends to work against current discrimination, it is not a remedy for past discrimination, which typically has had an impact on the education and experience of its victims and thereby reduces their income.

So Does Marginal Productivity Theory Work?

The main conclusion you should draw from this discussion is that the marginal productivity theory of income distribution is not a perfect description of how factor incomes are determined but that it works pretty well. The deviations are important. But, by and large, in a modern economy with well-

It’s important to emphasize, once again, that this does not mean that the factor distribution of income is morally justified.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Marginal Productivity and the “1%”

Marginal Productivity and the “1%”

In the fall of 2011, there were widespread public demonstrations in the United States and in a number of other countries against the growing inequality of personal income. U.S. protestors, known as the Occupy Wall Street movement, adopted the slogan “We are the 99%” to emphasize the fact that the incomes of the top 1% of the population had grown much faster than those of most Americans.

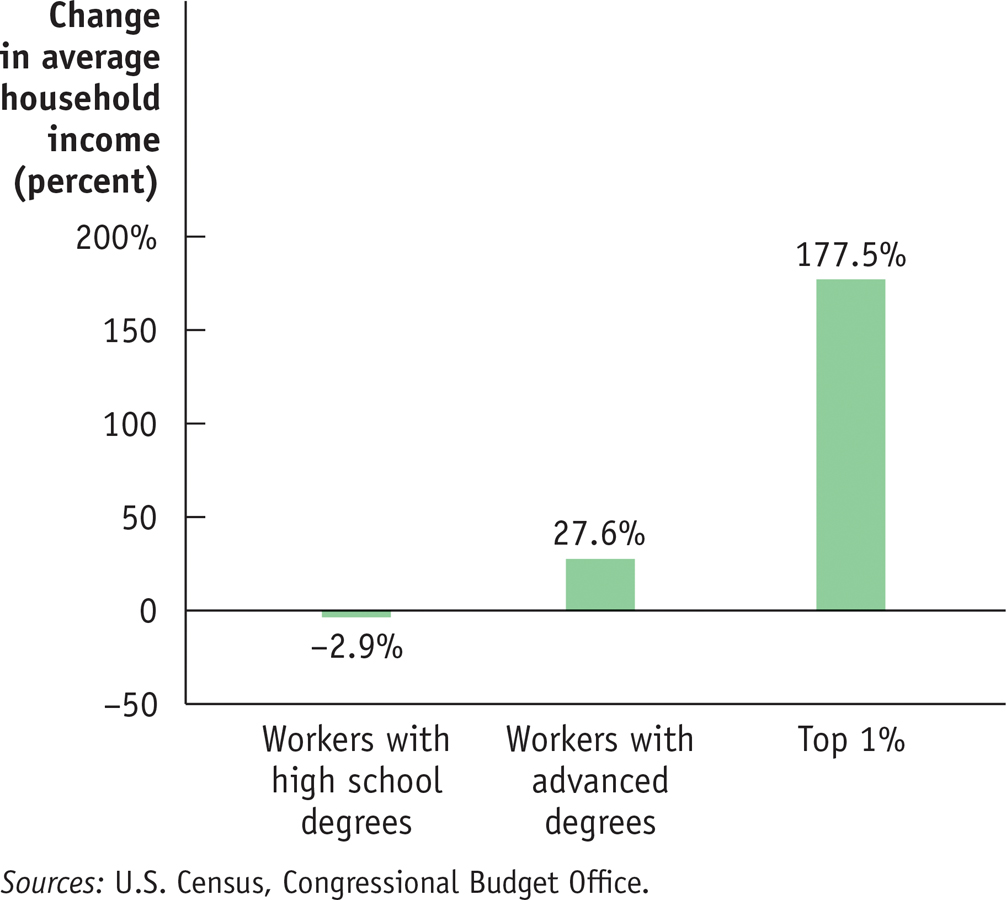

19-10

Income Changes, 1979-

Indeed, just as the protest movement was gathering strength, the Congressional Budget Office released a study on income inequality. The CBO found that, between 1979 and 2010, the income of the average household headed by a worker with a high school degree fell by 2.9%, while the income of the average household headed by a worker with an advanced degree rose by 27.6%. But the average income of the top 1% of households had risen 177.5%.

Why have the richest Americans been pulling away from the rest? The short answer is that the causes are a source of considerable dispute and continuing research. One thing is clear, however: this aspect of growing inequality can’t be explained simply in terms of the growing demand for highly educated labor. In this chapter’s opening story, we pointed out that there has been a growing wage premium for workers with advanced degrees. Yet despite this growing premium, as Figure 19-10 shows, such workers have seen only a fraction of the gains going to the top 1%.

This does not prove that the top 1% aren’t “earning” their incomes. It does show, however, that whatever the explanation for their huge gains, it’s not education.

Quick Review

Existing large disparities in wages both among individuals and across groups lead some to question the marginal productivity theory of income distribution.

Compensating differentials, as well as differences in the values of the marginal products of workers that arise from differences in talent, job experience, job status, and human capital, account for some wage disparities.

Market power, in the form of unions or collective action by employers, as well as the efficiency-

wage model , in which employers pay an above-equilibrium wage to induce better performance, also explain how some wage disparities arise. Discrimination has historically been a major factor in wage disparities. Market competition tends to work against discrimination. But discrimination can leave a long-

lasting legacy of diminished human capital acquisition.

19-3

Check Your Understanding

Question 19.6

Assess each of the following statements. Do you think they are true, false, or ambiguous? Explain.

The marginal productivity theory of income distribution is inconsistent with the presence of income disparities associated with gender, race, or ethnicity.

False. Income disparities associated with gender, race, or ethnicity can be explained by the marginal productivity theory of income distribution provided that differences in marginal productivity across people are correlated with gender, race, or ethnicity. One possible source for such correlation is past discrimination. Such discrimination can lower individuals’ marginal productivity by, for example, preventing them from acquiring the human capital that would raise their productivity. Another possible source of the correlation is differences in work experience that are associated with gender, race, or ethnicity. For example, in jobs where work experience or length of tenure is important, women may earn lower wages because on average more women than men take child-care-related absences from work.

Companies that engage in workplace discrimination but whose competitors do not are likely to have lower profits as a result of their actions.

True. Companies that discriminate when their competitors do not are likely to hire less able workers because they discriminate against more able workers who are considered to be of the wrong gender, race, ethnicity, or other characteristic. And with less able workers, such companies are likely to earn lower profits than their competitors that don’t discriminate.

Workers who are paid less because they have less experience are not the victims of discrimination.

Ambiguous. In general, workers who are paid less because they have less experience may or may not be the victims of discrimination. The answer depends on the reason for the lack of experience. If workers have less experience because they are young or have chosen to do something else rather than gain experience, then they are not victims of discrimination if they are paid less. But if workers lack experience because previous job discrimination prevented them from gaining experience, then they are indeed victims of discrimination when they are paid less.

Solutions appear at back of book.