Buying, Selling, and Reducing Risk

Lloyd’s of London is the oldest existing commercial insurance company, and it is an institution with an illustrious past. Originally formed in the eighteenth century to help merchants cope with the risks of commerce, it grew in the heyday of the British Empire into a mainstay of imperial trade.

The basic idea of Lloyd’s was simple. In the eighteenth century, shipping goods via sailing vessels was risky: the chance that a ship would sink in a storm or be captured by pirates was fairly high. The merchant who owned the ship and its cargo could easily be ruined financially by such an event. Lloyd’s matched shipowners seeking insurance with wealthy investors who promised to compensate a merchant if his ship were lost. In return, the merchant paid the investor a fee in advance; if his ship didn’t sink, the investor still kept the fee.

In effect, the merchant paid a price to relieve himself of risk. By matching people who wanted to purchase insurance with people who wanted to provide it, Lloyd’s performed the functions of a market. The fact that British merchants could use Lloyd’s to reduce their risk made many more people in Britain willing to undertake merchant trade.

Insurance companies have changed quite a lot from the early days of Lloyd’s. They no longer consist of wealthy individuals deciding on insurance deals over port and boiled mutton. But asking why Lloyd’s worked to the mutual benefit of merchants and investors is a good way to understand how the market economy as a whole “trades” and thereby transforms risk.

The insurance industry rests on two principles. The first is that trade in risk, like trade in any good or service, can produce mutual gains. In this case, the gains come when people who are less willing to bear risk transfer it to people who are more willing to bear it. The second is that some risk can be made to disappear through diversification. Let’s consider each principle in turn.

Trading Risk

It may seem a bit strange to talk about “trading” risk. After all, risk is a bad thing—

But people often trade away things they don’t like to other people who dislike them less. Suppose you have just bought a house for $100,000, the average price for a house in your community. But you have now learned, to your horror, that the building next door is being turned into a nightclub. You want to sell the house immediately and are willing to accept $95,000 for it. But who will now be willing to buy it? The answer: a person who doesn’t really mind late-

The key point is that the two parties have different sensitivities to noise, which enables those who most dislike noise, in effect, to pay other people to make their lives quieter. Trading risk works exactly the same way: people who want to reduce the risk they face can pay other people who are less sensitive to risk to take some of their risk away.

As we saw in the previous section, individual preferences account for some of the variations in people’s attitudes toward risk, but differences in income and wealth are probably the principal reason behind different risk sensitivities. Lloyd’s made money by matching wealthy investors who were more risk-

Suppose, staying with our Lloyd’s of London story, that a merchant whose ship went down would lose £1,000 and that there was a 10% chance of such a disaster. The expected loss in this case would be 0.10 × £1,000 = £100. But the merchant, whose whole livelihood was at stake, might have been willing to pay £150 to be compensated in the amount of £1,000 if the ship sank. Meanwhile, a wealthy investor for whom the loss of £1,000 was no big deal would have been willing to take this risk for a return only slightly better than the expected loss—

The funds that an insurer places at risk when providing insurance are called the insurer’s capital at risk.

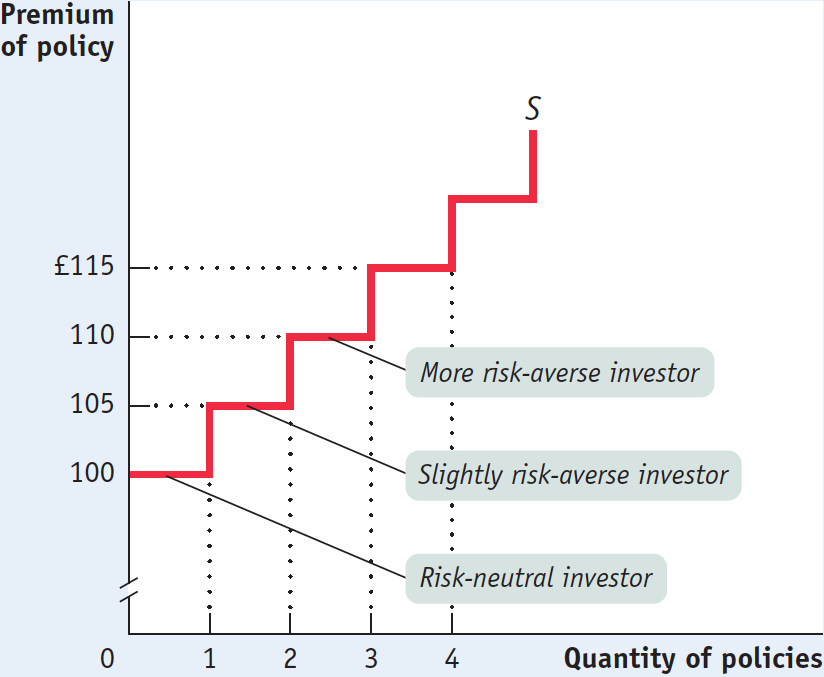

The funds that an insurer places at risk when providing insurance are called the insurer’s capital at risk. In our example, the wealthy Lloyd’s investor places capital of £1,000 at risk in return for a premium of £130. In general, the amount of capital that potential insurers are willing to place at risk depends, other things equal, on the premium offered. If every ship is worth £1,000 and has a 10% chance of going down, nobody would offer insurance for less than a £100 premium, equal to the expected claim. In fact, only an investor who isn’t risk-

Suppose there is one investor who is risk-

20-3

The Supply of Insurance

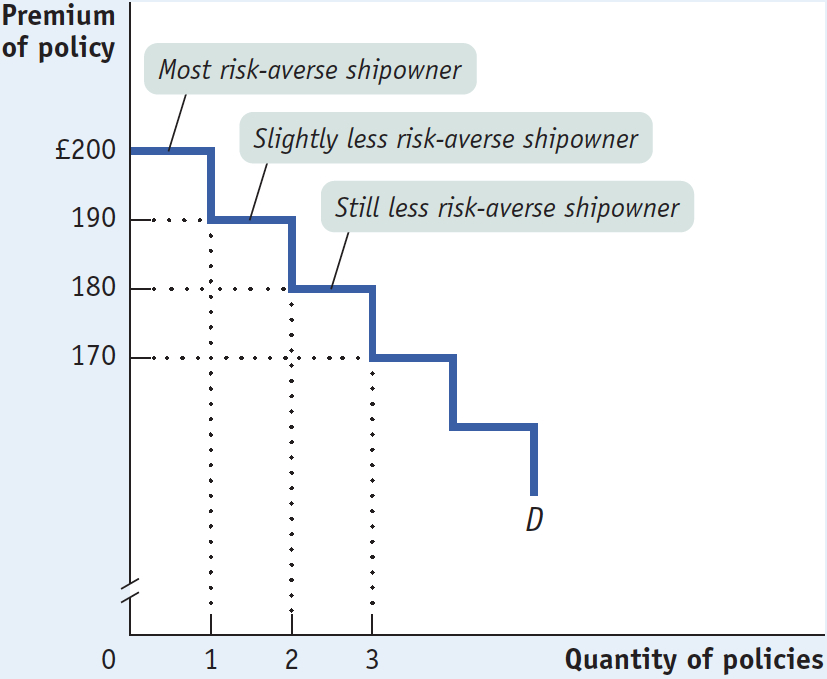

Meanwhile, potential buyers will consider their willingness to pay a given premium, defining the demand curve for insurance. In Figure 20-4, the highest premium that any shipowner is willing to pay is £200. Who’s willing to pay this? The most risk-

20-4

The Demand for Insurance

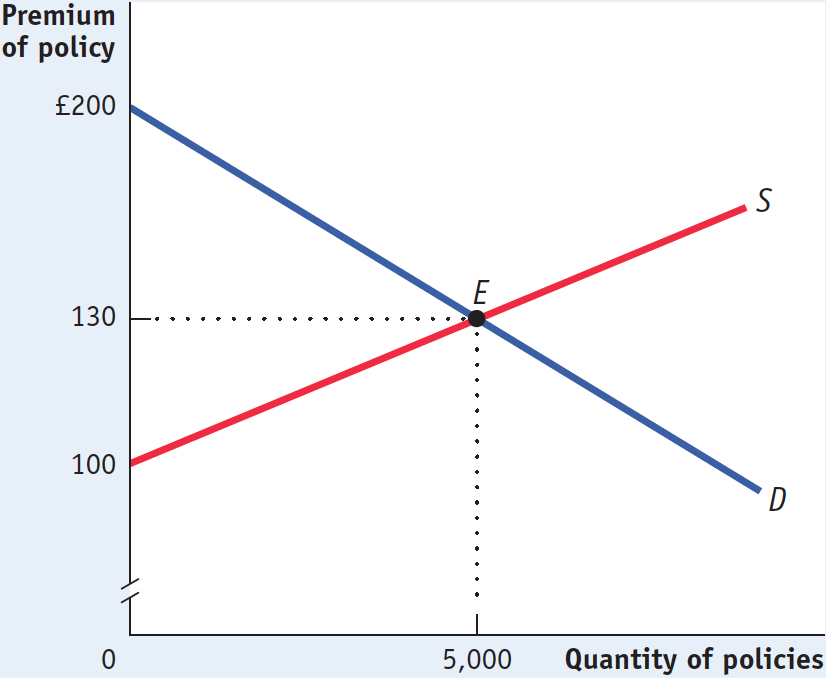

Now imagine a market in which there are thousands of shipowners and potential insurers, so that the supply and demand curves for insurance are smooth lines. In this market, as in markets for ordinary goods and services, there will be an equilibrium price and quantity. Figure 20-5 illustrates such a market equilibrium at a premium of £130, with a total quantity of 5,000 policies bought and sold, representing a total capital at risk of £5,000,000.

20-5

The Insurance Market

An efficient allocation of risk is an allocation of risk in which those who are most willing to bear risk are those who end up bearing it.

Notice that in this market risk is transferred from the people who most want to get rid of it (the most risk-

The trading of risk between individuals who differ in their degree of risk aversion plays an extremely important role in the economy, but it is not the only way that markets can help people cope with risk. Under some circumstances, markets can perform a sort of magic trick: they can make some (though rarely all) of the risk that individuals face simply disappear.

Making Risk Disappear: The Power of Diversification

In the early days of Lloyd’s, British merchant ships traversed the world, trading spices and silk from Asia, tobacco and rum from the New World, and textiles and wool from Britain, among other goods. Each of the many routes that British ships took had its own unique risks—

In the face of all these risks, how were merchants able to survive? One important way was by reducing their risks by not putting all their eggs in one basket: by sending different ships to different destinations, they could reduce the probability that all their ships would be lost. A strategy of investing in such a way as to reduce the probability of severe losses is known as diversification. As we’ll now see, diversification can often make some of the economy’s risk disappear.

Let’s stay with our shipping example. It was all too likely that a pirate might seize a merchant ship in the Caribbean or that a typhoon might sink another ship in the Indian Ocean. But the key point here is that the various threats to shipping didn’t have much to do with each other. So it was considerably less likely that a merchant who had one ship in the Caribbean and another ship in the Indian Ocean in a given year would lose them both, one to a pirate and the other to a typhoon. After all, there was no connection: the actions of cutthroats in the Caribbean had no influence on weather in the Indian Ocean, or vice versa.

Two possible events are independent events if each of them is neither more nor less likely to happen if the other one happens.

Statisticians refer to such events—

There is a simple rule for calculating the probability that two independent events will both happen: multiply the probability that one event would happen on its own by the probability that the other event would happen on its own. If you toss a coin once, the probability that it will come up heads is 0.5; if you toss the coin twice, the probability that it will come up heads both times is 0.5 × 0.5 = 0.25.

But what did it matter to shipowners or Lloyd’s investors that ship losses in the Caribbean and ship losses in the Indian Ocean were independent events? The answer is that by spreading their investments across different parts of the world, shipowners or Lloyd’s investors could make some of the riskiness of the shipping business simply disappear.

Let’s suppose that Joseph Moneypenny, Esq., is wealthy enough to outfit two ships—

Assume that both voyages will be equally profitable if successful, yielding £1,000 if the voyage is completed. Also assume that there is a 10% chance both that a ship sent to Barbados will run into a pirate and that a ship sent to Calcutta will be sunk by a typhoon. And if two ships travel to the same destination, we will assume that they share the same fate. So if Mr. Moneypenny were to send both his ships to either destination, he would face a probability of 10% of losing all his investment.

An individual can engage in diversification by investing in several different things, so that the possible losses are independent events.

But if Mr. Moneypenny were instead to send one ship to Barbados and one to Calcutta, the probability that he would lose both of them would be only 0.1 × 0.1 = 0.01, or just 1%. As we will see shortly, his expected payoff would be the same—

Table 20-2 summarizes Mr. Moneypenny’s options and their possible consequences. If he sends both ships to the same destination, he runs a 10% chance of losing them both. If he sends them to different destinations, there are three possible outcomes.

20-2

How Diversification Reduces Risk

|

(a) If both ships sent to the same destination |

|||

|

State |

Probability |

Payoff |

Expected payoff |

|

Both ships arrive |

0.9 = 90% |

£2,000 |

(0.9 × £2,000) + (0.1 × £0) = £1,800 |

|

Both ships lost |

0.1 = 10% |

0 |

|

|

(b) If one ship sent east, one west |

|||

|

State |

Probability |

Payoff |

Expected payoff |

|

Both ships arrive |

0.9 × 0.9 = 81% |

£2,000 |

|

|

Both ships lost |

0.1 × 0.1 = 1% |

0 |

(0.81 × £2,000) + (0.01 × £0) + (0.18 × £1,000) = £1,800 |

|

One ship arrives |

(0.9 × 0.1) + (0.1 × 0.9) = 18% |

1,000 |

|

TABLE 20-

Both ships could arrive safely: because there is a 0.9 probability of either one making it, the probability that both will make it is 0.9 × 0.9 = 81%.

Both could be lost—

but the probability of that happening is only 0.1 × 0.1 = 1%. Only one ship can arrive. The probability that the first ship arrives and the second ship is lost is 0.9 × 0.1 = 9%. The probability that the first ship is lost but the second ship arrives is 0.1 × 0.9 = 9%. So the probability that only one ship makes it is 9% + 9% = 18%.

You might think that diversification is a strategy available only to those with a lot of money to begin with. Can Mr. Moneypenny diversify if he is able to afford only one ship? There are ways for even small investors to diversify. Even if Mr. Moneypenny is only wealthy enough to equip one ship, he can enter a partnership with another merchant. They can jointly outfit two ships, agreeing to share the profits equally, and then send those ships to different destinations. That way each faces less risk than if he equips one ship alone.

A share in a company is a partial ownership of that company.

In the modern economy, diversification is made much easier for investors by the fact that they can easily buy shares in many companies by using the stock market. The owner of a share in a company is the owner of part of that company—

In fact, Lloyd’s of London wasn’t just a way to trade risks; it was also a way for investors to diversify. To see how this worked, let’s introduce Lady Penelope, a wealthy aristocrat, who decides to increase her income by placing £1,000 of her capital at risk via Lloyd’s. She could use that capital to insure just one ship. But more typically she would enter a “syndicate,” a group of investors, who would jointly insure a number of ships going to different destinations, agreeing to share the cost if any one of those ships went down. Because it would be much less likely for all the ships insured by the syndicate to sink than for any one of them to go down, Lady Penelope would be at much less risk of losing her entire capital.

Pooling is a strong form of diversification in which an investor takes a small share of the risk in many independent events. This produces a payoff with very little total overall risk.

In some cases, an investor can make risk almost entirely disappear by taking a small share of the risk in many independent events. This strategy is known as pooling.

Consider the case of a health insurance company, which has millions of policyholders, with thousands of them requiring expensive treatment each year. The insurance company can’t know whether any given individual will, say, require a heart bypass operation. But heart problems for two different individuals are pretty much independent events. And when there are many possible independent events, it is possible, using statistical analysis, to predict with great accuracy how many events of a given type will happen. For example, if you toss a coin 1,000 times, it will come up heads about 500 times—

So a company offering fire insurance can predict very accurately how many of its clients’ homes will burn down in a given year; a company offering health insurance can predict very accurately how many of its clients will need heart surgery in a given year; a life insurance company can predict how many of its clients will … Well, you get the idea.

When an insurance company is able to take advantage of the predictability that comes from aggregating a large number of independent events, it is said to engage in pooling of risks. And this pooling often means that even though insurance companies protect people from risk, the owners of the insurance companies may not themselves face much risk.

Lloyd’s of London wasn’t just a way for wealthy individuals to get paid for taking on some of the risks of less wealthy merchants. It was also a vehicle for pooling some of those risks. The effect of that pooling was to shift the supply curve in Figure 20-5 rightward: to make investors willing to accept more risk, at a lower price, than would otherwise have been possible.

Those Pesky Emotions

For a small investor (someone investing less than several hundred thousand dollars), financial economists agree that the best strategy for investing in stocks is to buy an index fund.

Why index funds? Because they contain a wide range of stocks that reflect the overall market, they achieve diversification; and they have very low management fees. In addition, financial economists agree that it’s a losing strategy to try to “time” the market: to buy when the stock market is low and sell when it’s high. Instead, small investors should buy a fixed dollar amount of stocks and other financial assets every year, regardless of the state of the market.

Yet many, if not most, small investors don’t follow this advice. Instead, they buy individual stocks or funds that charge high fees. They spend endless hours online chasing the latest hot tip or sifting through data trying to discern patterns in stocks’ behavior. They try to time the market but invariably buy when stocks are high and refuse to sell losers before they lose even more. And they fail to diversify, instead concentrating too much money in a few stocks they think are “winners.”

So why are human beings so dense when it comes to investing? According to experts, the culprit is emotion. In his book Your Money and Your Brain, Jason Zweig states, “the brain is not an optimal tool for making financial decisions.” As he explains it, the problem is that the human brain evolved to detect and interpret simple patterns. (Is there a lion lurking in that bush?) As a consequence, “when it comes to investing, our incorrigible search for patterns leads us to assume that order exists where it often doesn’t.” In other words, investors fool themselves into believing that they’ve discovered a lucrative stock market pattern when, in fact, stock market behavior is largely random. Not surprisingly, how people make financial decisions is a major topic of study in the area of behavioral economics, a branch of economics that studies why human beings often fail to behave rationally (as covered in Chapter 9).

So, what’s the typical twenty-

The Limits of Diversification

Diversification can reduce risk. In some cases it can eliminate it. But these cases are not typical, because there are important limits to diversification. We can see the most important reason for these limits by returning to Lloyd’s one more time.

In Lloyd’s early days, there was one important hazard facing British shipping other than pirates or storms: war. Between 1690 and 1815, Britain fought a series of wars, mainly with France (which, among other things, went to war with Britain in support of the American Revolution). Each time, France would sponsor “privateers”—basically pirates with official backing—

Whenever war broke out between Britain and France, losses of British merchant ships would increase. Unfortunately, merchants could not protect themselves against this eventuality by sending ships to different ports: the privateers would prey on British ships anywhere in the world. So the loss of a ship to French privateers in the Caribbean and the loss of another ship to French privateers in the Indian Ocean would not be independent events. It would be quite likely that they would happen in the same year.

Two events are positively correlated if each event is more likely to occur if the other event also occurs.

When an event is more likely to occur if some other event occurs, these two events are said to be positively correlated. And like the risk of having a ship seized by French privateers, many financial risks are, alas, positively correlated.

Here are some of the positively correlated financial risks that investors in the modern world face:

Severe weather. Within any given region of the United States, losses due to weather are definitely not independent events. When a hurricane hits Florida, a lot of Florida homes will suffer hurricane damage. To some extent, insurance companies can diversify away this risk by insuring homes in many states. But events like El Niño (a recurrent temperature anomaly in the Pacific Ocean that disrupts weather around the world) can cause simultaneous flooding across the United States. And as we mentioned in our opening story, over the past several years, there has been a significant increase in extreme weather.

Political events. Modern governments do not, thankfully, license privateers—

although submarines served much the same function during World War II. Even today, however, some kinds of political events— say, a war or revolution in a key raw- material- producing area— can damage business around the globe. Business cycles. The causes of business cycles, fluctuations in the output of the economy as a whole, are a subject for macroeconomics. What we can say here is that if one company suffers a decline in business because of a nationwide economic slump, many other companies will also suffer such declines. So these events will be positively correlated.

When events are positively correlated, the risks they pose cannot be diversified away. An investor can protect herself from the risk that any one company will do badly by investing in many companies; she cannot use the same technique to protect against an economic slump in which all companies do badly.

An insurance company can protect itself against the risk of losses from local flooding by insuring houses in many different places; but a global weather pattern that produces floods in many places will defeat this strategy. Not surprisingly, insurers pulled back from writing policies when it became clear that extreme weather patterns had become worse. They could no longer be confident that profits from policies written in good weather areas would be sufficient to compensate for losses incurred on policies in hurricane and drought prone areas.

So institutions like insurance companies and stock markets cannot make risk go away completely. There is always an irreducible core of risk that cannot be diversified. Markets for risk, however, do accomplish two things: First, they enable the economy to eliminate the risk that can be diversified. Second, they allocate the risk that remains to the people most willing to bear it.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: When Lloyd’s Almost Lost It

When Lloyd’s Almost Lost It

At the end of the 1980s, the venerable institution of Lloyd’s found itself in severe trouble. Investors who had placed their capital at risk, believing that the risks were small and the return on their investments more or less assured, found themselves required to make large payments to satisfy enormous claims. A number of investors, including members of some very old aristocratic families, found themselves pushed into bankruptcy.

What happened? Part of the answer is that ambitious managers at Lloyd’s had persuaded investors to take on risks that were much larger than the investors realized. (Or to put it a different way, the premiums the investors accepted were too small for the true level of risk contained in the policies.)

But the biggest single problem was that many of the events against which Lloyd’s had become a major insurer were not independent. In the 1970s and 1980s, Lloyd’s had become a major provider of corporate liability insurance in the United States: it protected American corporations against the possibility that they might be sued for selling defective or harmful products. Everyone expected such suits to be more or less independent events. Why should one company’s legal problems have much to do with another’s?

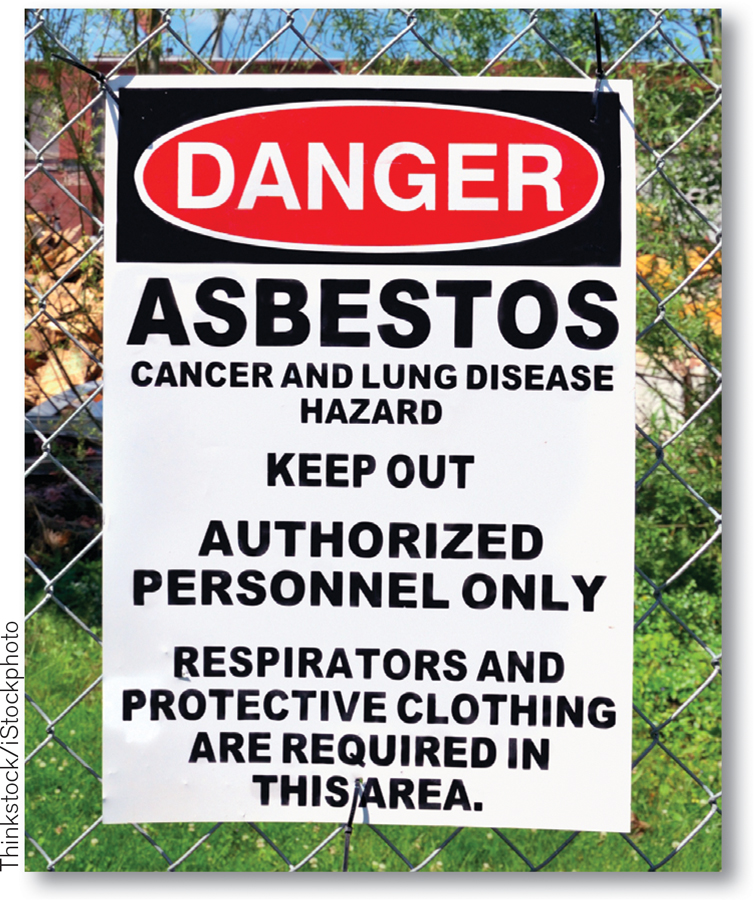

The answer turned out to lie in one word: asbestos. For decades, this fire-

Quick Review

Insurance markets exist because there are gains from trade in risk. Except in the case of private information, they lead to an efficient allocation of risk: those who are most willing to bear risk place their capital at risk to cover the financial losses of those least willing to bear risk.

When independent events are involved, a strategy of diversification can substantially reduce risk. Diversification is made easier by the existence of institutions like the stock market, in which people trade shares of companies. A form of diversification, relevant especially to insurance companies, is pooling.

When events are positively correlated, there is a core of risk that cannot be eliminated, no matter how much individuals diversify.

20-2

Question 20.3

Explain how each of the following events would change the equilibrium premium and quantity of insurance in the market, indicating any shifts in the supply and demand curves.

An increase in the number of ships traveling the same trade routes and so facing the same kinds of risks

An increase in the number of ships implies an increase in the quantity of insurance demanded at any given premium. This is a rightward shift of the demand curve, resulting in a rise in both the equilibrium premium and the equilibrium quantity of insurance bought and sold.

An increase in the number of trading routes, with the same number of ships traveling a greater variety of routes and so facing different kinds of risk

An increase in the number of trading routes means that investors can diversify more. In other words, they can reduce risk further. At any given premium, there are now more investors willing to supply insurance. This is a rightward shift of the supply curve for insurance, leading to a fall in the equilibrium premium and a rise in the equilibrium quantity of insurance bought and sold.

An increase in the degree of risk aversion among the shipowners in the market

If shipowners in the market become even more risk-averse, they will be willing to pay even higher premiums for insurance. That is, at any given premium, there are now more people willing to buy insurance. This is a rightward shift of the demand curve for insurance, leading to a rise in both the equilibrium premium and the equilibrium quantity of insurance bought and sold.

An increase in the degree of risk aversion among the investors in the market

If investors in the market become more risk-averse, they will be less willing to accept risk at any given premium. This is a leftward shift of the supply curve for insurance, leading to a rise in the equilibrium premium and a fall in the equilibrium quantity of insurance bought and sold.

An increase in the risk affecting the economy as a whole

As the overall level of risk increases, those willing to buy insurance will be more willing to buy insurance at any given premium; the demand curve for insurance shifts to the right. But since overall risk cannot be diversified away, those ordinarily willing to take on risk will be less willing to do so, leading to a leftward shift in the supply curve for insurance. As a result, the equilibrium premium will rise; the effect on the equilibrium quantity of insurance is uncertain.

A fall in the wealth levels of investors in the market

If the wealth levels of investors fall, investors will become more risk-averse and so less willing to supply insurance at any given premium. This is a leftward shift of the supply curve for insurance, leading to a rise in the equilibrium premium and a fall in the equilibrium quantity of insurance bought and sold.

Solutions appear at back of book.