Taxes

7

What You Will Learn in This Chapter

What You Will Learn in This Chapter

The effects of taxes on supply and demand

What determines who really bears the burden of a tax

The costs and benefits of taxes, and why taxes impose a cost that is greater than the tax revenue they raise

The difference between progressive and regressive taxes and the trade-

off between tax equity and tax efficiency The structure of the U.S. tax system

THE FOUNDING TAXERS

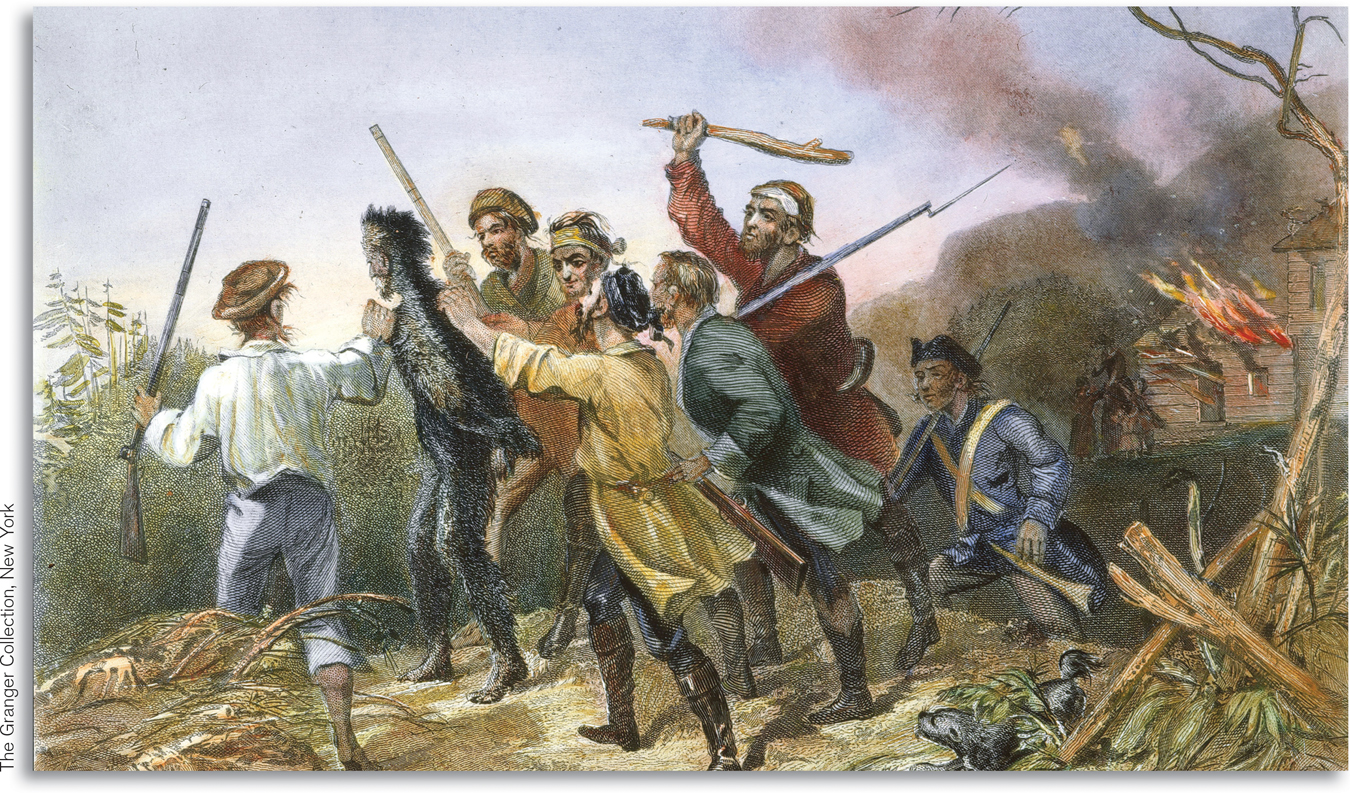

IN 1794, LONG-

It wouldn’t be surprising if you mistook this as an episode from the French Revolution. But, in fact, it occurred in western Pennsylvania—

So what was the fighting about? Taxes. Facing a large debt after the War of Independence and unable to raise taxes any higher on imported goods, the Washington administration, at the suggestion of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamiton, enacted a tax on whiskey distillers in 1791. Whiskey was a popular drink at the time, so such a tax could raise a lot of revenue. Meantime, a tax would encourage more “upstanding behavior” on the part of the young country’s hard-

Yet the way the tax was applied was perceived as deeply unfair. Distillers could either pay a flat amount or pay by the gallon. Large distillers could afford the flat amount, but small distillers could not and paid by the gallon. As a result, the small distillers—

Moreover, in the frontier of western Pennsylvania, cash was commonly hard to acquire and whiskey was often used as payment in transactions. By discouraging small distillers from producing whiskey, the tax left the local economy with less income and fewer means to buy and sell others goods.

Although the rebellion against the whiskey tax was eventually put down, the political party that supported the tax—

There are two main morals to this story. One, taxes are necessary: all governments need money to function. Without taxes, governments could not provide the services we want, from national defense to public parks. But taxes have a cost that normally exceeds the money actually paid to the government. That’s because taxes distort incentives to engage in mutually beneficial transactions.

And that leads us to the second moral: making tax policy isn’t easy—

One principle used for guiding tax policy is efficiency: taxes should be designed to distort incentives as little as possible. But efficiency is not the only concern when designing tax rates. As the Washington administration learned from the Whiskey Rebellion, it’s also important that a tax be seen as fair. Tax policy always involves striking a balance between the pursuit of efficiency and the pursuit of perceived fairness.

In this chapter, we will look at how taxes affect efficiency and fairness as well as raise revenue for the government.