Costs, Benefits, and Profits

In making any type of decision, it’s critical to define the costs and benefits of that decision accurately. If you don’t know the costs and benefits, it is nearly impossible to make a good decision. So that is where we begin.

An important first step is to recognize the role of opportunity cost, a concept we first encountered in Chapter 1, where we learned that opportunity costs arise because resources are scarce. Because resources are scarce, the true cost of anything is what you must give up to get it—

Whether you decide to continue in school for another year or leave to find a job, each choice has costs and benefits. Because your time—

When making decisions, it is crucial to think in terms of opportunity cost, because the opportunity cost of an action is often considerably more than the cost of any outlays of money.

Economists use the concepts of explicit costs and implicit costs to compare the relationship between opportunity costs and monetary outlays. We’ll discuss these two concepts first. Then we’ll define the concepts of accounting profit and economic profit, which are ways of measuring whether the benefit of an action is greater than the cost. Armed with these concepts for assessing costs and benefits, we will be in a position to consider our first principle of economic decision making: how to make “either–

Explicit versus Implicit Costs

Suppose that, after graduating from college, you have two options: to go to school for an additional year to get an advanced degree or to take a job immediately. You would like to enroll in the extra year in school but are concerned about the cost.

What exactly is the cost of that additional year of school? Here is where it is important to remember the concept of opportunity cost: the cost of the year spent getting an advanced degree includes what you forgo by not taking a job for that year. The opportunity cost of an additional year of school, like any cost, can be broken into two parts: the explicit cost of the year’s schooling and the implicit cost.

An explicit cost is a cost that requires an outlay of money.

An explicit cost is a cost that requires an outlay of money. For example, the explicit cost of the additional year of schooling includes tuition. An implicit cost, though, does not involve an outlay of money. Instead, it is measured by the value, in dollar terms, of the benefits that are forgone. For example, the implicit cost of the year spent in school includes the income you would have earned if you had taken a job instead.

An implicit cost does not require an outlay of money. It is measured by the value, in dollar terms, of benefits that are forgone.

A common mistake, both in economic analysis and in life—

Table 9-1 gives a breakdown of hypothetical explicit and implicit costs associated with spending an additional year in school instead of taking a job. The explicit cost consists of tuition, books, supplies, and a computer for doing assignments—

9-1

Opportunity Cost of an Additional Year of School

|

Explicit cost |

Implicit cost |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Tuition |

$7,000 |

Forgone salary |

$35,000 |

|

Books and supplies |

1,000 |

|

|

|

Computer |

1,500 |

|

|

|

Total explicit cost |

9,500 |

Total implicit cost |

35,000 |

|

Total opportunity cost = Total explicit cost + Total implicit cost = $44,500 |

|||

TABLE 9-

A slightly different way of looking at the implicit cost in this example can deepen our understanding of opportunity cost. The forgone salary is the cost of using your own resources—

Understanding the role of opportunity costs makes clear the reason for the surge in school applications in 2010: a rotten job market. Starting in 2009, the U.S. job market deteriorated sharply as the economy entered a severe recession. By 2010, the job market was still quite weak; although job openings had begun to reappear, a relatively high proportion of those openings were for jobs with low wages and no benefits. As a result, the opportunity cost of another year of schooling had declined significantly, making spending another year at school a much more attractive choice than when the job market was strong.

Accounting Profit versus Economic Profit

Let’s return to Ashley Hildreth and assume that she faces the choice of either completing a two-

To get started, let’s consider what Ashley gains by getting the teaching degree—

Accounting profit is equal to revenue minus explicit cost.

At this point, what she should do might seem obvious: if she chooses the teaching degree, she gets a lifetime increase in the value of her earnings of $600,000 − $500,000 = $100,000, and she pays $40,000 in tuition plus $4,000 in interest. Doesn’t that mean she makes a profit of $100,000 −$40,000 − $4,000 = $56,000 by getting her teaching degree? This $56,000 is Ashley’s accounting profit from obtaining her teaching degree: her revenue minus her explicit cost. In this example her explicit cost of getting the degree is $44,000, the amount of her tuition plus student loan interest.

Economic profit is equal to revenue minus the opportunity cost of resources used. It is usually less than the accounting profit.

Although accounting profit is a useful measure, it would be misleading for Ashley to use it alone in making her decision. To make the right decision, the one that leads to the best possible economic outcome for her, she needs to calculate her economic profit—the revenue she receives from the teaching degree minus her opportunity cost of staying in school (which is equal to her explicit cost plus her implicit cost). In general, the economic profit of a given project will be less than the accounting profit because there are almost always implicit costs in addition to explicit costs.

When economists use the term profit, they are referring to economic profit, not accounting profit. This will be our convention in the rest of the book: when we use the term profit, we mean economic profit.

How does Ashley’s economic profit from staying in school differ from her accounting profit? We’ve already encountered one source of the difference: her two years of forgone job earnings. This is an implicit cost of going to school full time for two years. We assume that the value today of Ashley’s forgone earnings for the two years is $57,000.

Once we factor in Ashley’s implicit costs and calculate her economic profit, we see that she is better off not getting a teaching degree. You can see this in Table 9-2: her economic profit from getting the teaching degree is −$1,000. In other words, she incurs an economic loss of $1,000 if she gets the degree. Clearly, she is better off sticking to advertising and going to work now.

9-2

Ashley’s Economic Profit from Acquiring Teaching Degree

|

Value of increase in lifetime earnings |

$100,000 |

|

Explicit cost: |

|

|

Tuition |

−40,000 |

|

Interest paid on student loan |

− 4,000 |

|

Accounting Profit |

56,000 |

|

Implicit cost: |

|

|

Value of income forgone during 2 years spent in school |

−57,000 |

|

Economic Profit |

−1,000 |

TABLE 9-

Let’s consider a slightly different scenario to make sure that the concepts of opportunity costs and economic profit are well understood. Let’s suppose that Ashley does not have to take out $40,000 in student loans to pay her tuition. Instead, she can pay for it with an inheritance from her grandmother. As a result, she doesn’t have to pay $4,000 in interest. In this case, her accounting profit is $60,000 rather than $56,000. Would the right decision now be for her to get the teaching degree? Wouldn’t the economic profit of the degree now be $60,000 −$57,000 = $3,000?

The answer is no, because in this scenario Ashley is using her own capital to finance her education, and the use of that capital has an opportunity cost even when she owns it.

Capital is the total value of assets owned by an individual or firm—

Capital is the total value of the assets of an individual or a firm. An individual’s capital usually consists of cash in the bank, stocks, bonds, and the ownership value of real estate such as a house. In the case of a business, capital also includes its equipment, its tools, and its inventory of unsold goods and used parts. (Economists like to distinguish between financial assets, such as cash, stocks, and bonds, and physical assets, such as buildings, equipment, tools, and inventory.)

The point is that even if Ashley owns the $40,000, using it to pay tuition incurs an opportunity cost—

To keep things simple, let’s assume that she earns $4,000 on that $40,000 once it is deposited in a bank. Now, rather than pay $4,000 in explicit costs in the form of student loan interest, Ashley pays $4,000 in implicit costs from the forgone interest she could have earned.

The implicit cost of capital is the opportunity cost of the use of one’s own capital—

This $4,000 in forgone interest earnings is what economists call the implicit cost of capital—the income the owner of the capital could have earned if the capital had been employed in its next best alternative use. The net effect is that it makes no difference whether Ashley finances her tuition with a student loan or by using her own funds. This comparison reinforces how carefully you must keep track of opportunity costs when making a decision.

Making “Either–Or” Decisions

An “either–

9-3

“How Much” versus “Either-Or” Decisions

|

“Either- |

“How much” decisions |

|---|---|

|

Tide or Cheer? |

How many days before you do your laundry? |

|

Buy a car or not? |

How many miles do you go before an oil change in your car? |

|

An order of nachos or a sandwich? |

How many jalapenos on your nachos? |

|

Run your own business or work for someone else? |

How many workers should you hire in your company? |

|

Prescribe drug A or drug B for your patients? |

How much should a patient take of a drug that generates side effects? |

|

Graduate school or not? |

How many hours to study? |

TABLE 9-

According to the principle of “either–

In making economic decisions, as we have already emphasized, it is vitally important to calculate opportunity costs correctly. The best way to make an “either–

Let’s examine Ashley’s dilemma from a different angle to understand how this principle works. If she continues with advertising and goes to work immediately, the value today of her total lifetime earnings is $57,000 (the value today of her earnings over the next two years) + $500,000 (the value today of her total lifetime earnings thereafter) = $557,000. If she gets her teaching degree instead and works as a teacher, the value today of her total lifetime earnings is $600,000 (value today of her lifetime earnings after two years in school) − $40,000 (tuition) − $4,000 (interest payments) = $556,000. The economic profit from continuing in advertising versus becoming a teacher is $557,000 − $556,000 = $1,000.

A Tale of Two Invasions

ON JUNE 6, 1944, ALLIED SOLDIERS stormed the beaches of Normandy, beginning the liberation of France from German rule. Long before the assault, however, Allied generals had to make a crucial decision: where would the soldiers land?

They had to make an “either–

Thirty years earlier, at the beginning of World War I, German generals had to make a different kind of decision. They, too, planned to invade France, in this case via land, and had decided to mount that invasion through Belgium. The decision they had to make was not an “either–

So Allied generals made the right “either–

So the right choice for Ashley is to begin work in advertising immediately, which gives her an economic profit of $1,000, rather than become a teacher, which would give her an economic profit of −$1,000. In other words, by becoming a teacher she loses the $1,000 economic profit she would have gained by working in advertising immediately.

In making “either–

PITFALLS: WHY ARE THERE ONLY TWO CHOICES?

WHY ARE THERE ONLY TWO CHOICES?

In “either–

Yes, it does. That’s because any choice between three (or more) alternatives can always be boiled down to a series of choices between two alternatives. Here’s an illustration using three alternative activities: A, B, or C. (Remember that this is an “either–

Let’s say you begin by considering A versus B: in this comparison, A has a positive economic profit but B yields an economic loss. At this point, you should discard B as a viable choice because A will always be superior to B. The next step is to compare A to C: in this comparison, C has a positive economic profit but A yields an economic loss. You can now discard A because C will always be superior to A. You are now done: since A is better than B, and C is better than A, C is the correct choice.

In addition, businesses run by the owner (an entrepreneur) often fail to calculate the opportunity cost of the owner’s time in running the business. In that way, small businesses often underestimate their opportunity costs and overestimate their economic profit of staying in business.

Are we implying that the hundreds of thousands who have chosen to go back to school rather than find work in recent years are misguided? Not necessarily. As we mentioned before, the poor job market has greatly diminished the opportunity cost of forgone wages for many students, making continuing their education the optimal choice for them.

The following Economics in Action illustrates just how important it is in real life to understand the difference between accounting profit and economic profit.

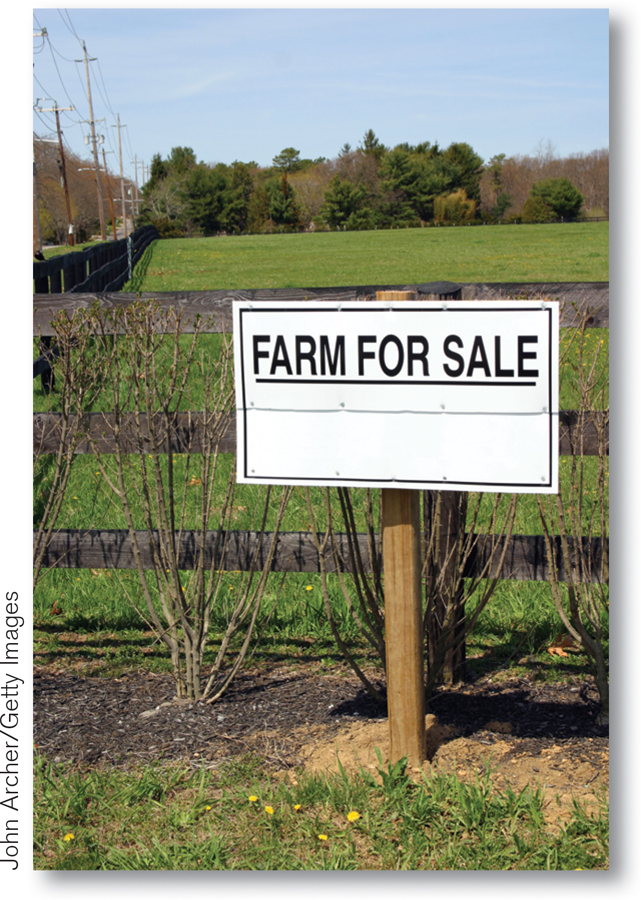

ECONOMICS in Action: Farming in the Shadow of Suburbia

Farming in the Shadow of Suburbia

Beyond the sprawling suburbs, most of New England is covered by dense forest. But this is not the forest primeval: if you hike through the woods, you encounter many stone walls, relics of the region’s agricultural past when stone walls enclosed fields and pastures. In 1880, more than half of New England’s land was farmed; by 2013, the amount was down to 10%.

The remaining farms of New England are mainly located close to large metropolitan areas. There farmers get high prices for their produce from city dwellers who are willing to pay a premium for locally grown, extremely fresh fruits and vegetables.

But now even these farms are under economic pressure caused by a rise in the implicit cost of farming close to a metropolitan area. As metropolitan areas have expanded during the last two decades, farmers increasingly ask themselves whether they could do better by selling their land to property developers.

In 2013, the average value of an acre of farmland in the United States as a whole was $2,900; in Rhode Island, the most densely populated of the New England states, the average was $11,800. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston has noted that “high land prices put intense pressure on the region’s farms to generate incomes that are substantial enough to justify keeping the land in agriculture.”

The important point is that the pressure is intense even if the farmer owns the land because the land is a form of capital used to run the business. So maintaining the land as a farm instead of selling it to a developer constitutes a large implicit cost of capital.

A fact provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) helps us put a dollar figure on the portion of the implicit cost of capital due to development pressure for some Rhode Island farms. In 2004, a USDA program designed to prevent development of Rhode Island farmland by paying owners for the “development rights” to their land paid an average of $4,949 per acre for those rights alone. By 2013, the amount had risen to more than $11,800.

About two-

Quick Review

All costs are opportunity costs. They can be divided into explicit costs and implicit costs.

An activity’s accounting profit is not necessarily equal to its economic profit.

Due to the implicit cost of capital—the opportunity cost of using self-

owned capital—and the opportunity cost of one’s own time, economic profit is often substantially less than accounting profit. The principle of “either–

or” decision making says that when making an “either–or” choice between two activities, choose the one with the positive economic profit.

9-1

Question 9.1

Karma and Don run a furniture-

refinishing business from their home. Which of the following represent an explicit cost of the business and which represent an implicit cost? Supplies such as paint stripper, varnish, polish, sandpaper, and so on

Supplies are an explicit cost because they require an outlay of money.Basement space that has been converted into a workroom

If the basement could be used in some other way that generates money, such as renting it to a student, then the implicit cost is that money forgone. Otherwise, the implicit cost is zero.Wages paid to a part-

time helper Wages are an explicit cost.A van that they inherited and use only for transporting furniture

By using the van for their business, Karma and Don forgo the money they could have gained by selling it. So use of the van is an implicit cost.The job at a larger furniture restorer that Karma gave up in order to run the business

Karma’s forgone wages from her job are an implicit cost.

Question 9.2

Assume that Ashley has a third alternative to consider: entering a two-

year apprenticeship program for skilled machinists that would, upon completion, make her a licensed machinist. During the apprenticeship, she earns a reduced salary of $15,000 per year. At the end of the apprenticeship, the value of her lifetime earnings is $725,000. What is Ashley’s best career choice? We need only compare the choice of becoming a machinist to the choice of taking a job in advertising in order to make the right choice. We can discard the choice of acquiring a teaching degree because we already know that taking a job in advertising is always superior to it. Now let’s compare the remaining two alternatives: becoming a skilled machinist versus immediately taking a job in advertising. As an apprentice machinist, Ashley will earn only $30,000 over the first two years, versus $57,000 in advertising. So she has an implicit cost of $30,000 – $57,000 = – $27,000 by becoming a machinist instead of immediately working in advertising. However, two years from now the value of her lifetime earnings as a machinist is $725,000 versus $600,000 in advertising, giving her an accounting profit of $125,000 by choosing to be a machinist. Summing, her economic profit from choosing a career as a machinist over a career in advertising is $125,000 – $27,000 = $98,000. In contrast, her economic profit from choosing the alternative, a career in advertising over a career as a machinist, is – $125,000 + $27,000 = – $98,000. By the principle of “either-or” decision making, Ashley should choose to be a machinist because that career has a positive economic profit.Question 9.3

Suppose you have three alternatives—

A, B, and C— and you can undertake only one of them. In comparing A versus B, you find that B has an economic profit and A yields an economic loss. But in comparing A versus C, you find that C has an economic profit and A yields an economic loss. How do you decide what to do? You can discard alternative A because both B and C are superior to it. But you must now compare B versus C. You should then choose the alternative—B or C—that carries a positive economic profit.

Solutions appear at back of book.