Behavioral Economics

Most economic models assume that people make choices based on achieving the best possible economic outcome for themselves. Human behavior, however, is often not so simple. Rather than acting like economic computing machines, people often make choices that fall short—

Why people sometimes make less-

It’s well documented that people consistently engage in irrational behavior, choosing an option that leaves them worse off than other available options. Yet, as we’ll soon learn, sometimes it’s entirely rational for people to make a choice that is different from the one that generates the highest possible profit for themselves. For example, Ashley may decide to earn a teaching degree because she enjoys teaching more than advertising, even though the profit from the teaching degree is less than that from continuing with advertising.

The study of irrational economic behavior was largely pioneered by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics for his work integrating insights from the psychology of human judgment and decision making into economics. Their work and the insights of others into why people often behave irrationally are having a significant influence on how economists analyze financial markets, labor markets, and other economic concerns.

Rational, but Human, Too

A rational decision maker chooses the available option that leads to the outcome he or she most prefers.

If you are rational, you will choose the available option that leads to the outcome you most prefer. But is the outcome you most prefer always the same as the one that gives you the best possible economic payoff? No. It can be entirely rational to choose an option that gives you a worse economic payoff because you care about something other than the size of the economic payoff. There are three principal reasons why people might prefer a worse economic payoff: concerns about fairness, bounded rationality, and risk aversion.

Concerns About Fairness In social situations, people often care about fairness as well as about the economic payoff to themselves. For example, no law requires you to tip a waiter or waitress. But concern for fairness leads most people to leave a tip (unless they’ve had outrageously bad service) because a tip is seen as fair compensation for good service according to society’s norms. Tippers are reducing their own economic payoff in order to be fair to waiters and waitresses. A related behavior is gift-

A decision maker operating with bounded rationality makes a choice that is close to but not exactly the one that leads to the best possible economic outcome.

Bounded Rationality Being an economic computing machine—

Retailers are particularly good at exploiting their customers’ tendency to engage in bounded rationality. For example, pricing items in units ending in 99¢ takes advantage of shoppers’ tendency to interpret an item that costs, say, $2.99 as significantly cheaper than one that costs $3.00. Bounded rationality leads them to give more weight to the $2 part of the price (the first number they see) than the 99¢ part. And retailers also make use of shoppers’ tendency to engage in what social scientists call anchoring, making decisions according to some perceived benchmark or reference point. For example, retailers attempt to influence shoppers’ belief about whether they are getting a good deal by showing both the full price (the anchor) and the discounted price.

Risk Aversion Because life is uncertain and the future unknown, sometimes a choice comes with significant risk. Although you may receive a high payoff if things turn out well, the possibility also exists that things may turn out badly and leave you worse off.

Risk aversion is the willingness to sacrifice some economic payoff in order to avoid a potential loss.

So even if you think a choice will give you the best payoff of all your available options, you may forgo it because you find the possibility that things could turn out badly too, well, risky. This is called risk aversion—the willingness to sacrifice some potential economic payoff in order to avoid a potential loss. (We’ll discuss risk in detail in Chapter 20.) Because risk makes most people uncomfortable, it’s rational for them to give up some potential economic gain in order to avoid it. In fact, if it weren’t for risk aversion, there would be no such thing as insurance.

Irrationality: An Economist’s View

An irrational decision maker chooses an option that leaves him or her worse off than choosing another available option.

Sometimes, though, instead of being rational, people are irrational—they make choices that leave them worse off in terms of economic payoff and other considerations like fairness than if they had chosen another available option. Is there anything systematic that economists and psychologists can say about economically irrational behavior? Yes, because most people are irrational in predictable ways. People’s irrational behavior typically stems from six mistakes they make when thinking about economic decisions. The mistakes are listed in Table 9-8, and we will discuss each in turn.

9-8

The Six Common Mistakes in Economic Decision Making

|

1. Misperceiving opportunity costs |

|

2. Being overconfident |

|

3. Having unrealistic expectations about future behavior |

|

4. Counting dollars unequally |

|

5. Being loss- |

|

6. Having a bias toward the status quo |

TABLE 9-

Misperceptions of Opportunity Costs As we discussed at the beginning of this chapter, people tend to ignore nonmonetary opportunity costs—

Overconfidence It’s a function of ego: we tend to think we know more than we actually do. And even if alerted to how widespread overconfidence is, people tend to think that it’s someone else’s problem, not theirs. (Certainly not yours or mine!)

For example, a 1994 study asked students to estimate how long it would take them to complete their thesis “if everything went as well as it possibly could” and “if everything went as poorly as it possibly could.” The results: the typical student thought it would take him or her 33.9 days to finish, with an average estimate of 27.4 days if everything went well and 48.6 days if everything went poorly. In fact, the average time it took to complete a thesis was much longer, 55.5 days. Students were, on average, from 14% to 102% more confident than they should have been about the time it would take to complete their thesis.

In Praise of Hard Deadlines

Dan Ariely, a professor of psychology and behavioral economics, likes to do experiments with his students that help him explore the nature of irrationality. In his book Predictably Irrational, Ariely describes an experiment that gets to the heart of procrastination and ways to address it.

At the time, Ariely was teaching the same subject matter to three different classes, but he gave each class different assignment schedules. The grade in all three classes was based on three equally weighted papers.

Students in the first class were required to choose their own personal deadlines for submitting each paper. Once set, the deadlines could not be changed. Late papers would be penalized at the rate of 1% of the grade for each day late. Papers could be turned in early without penalty but also without any advantage, since Ariely would not grade papers until the end of the semester.

Students in the second class could turn in the three papers whenever they wanted, with no preset deadlines, as long as it was before the end of the term. Again, there would be no benefit for early submission.

Students in the third class faced what Ariely called the “dictatorial treatment.” He established three hard deadlines at the fourth, eighth, and twelfth weeks.

So which classes do you think achieved the best and the worst grades? As it turned out, the class with the least flexible deadlines—

Ariely learned two simple things about overconfidence from these results. First—

But the biggest revelation came from the class that set its own deadlines. The majority of those students spaced their deadlines far apart and got grades as good as those of the students under the dictatorial treatment. Some, however, did not space their deadlines far enough apart, and a few did not space them out at all. These last two groups did less well, putting the average of the entire class below the average of the class with the least flexibility. As Ariely notes, without well-

This experiment provides two important insights:

People who acknowledge their tendency to procrastinate are more likely to use tools for committing to a path of action.

Providing those tools allows people to make themselves better off.

If you have a problem with procrastination, hard deadlines, as irksome as they may be, are truly for your own good.

As you can see in the following For Inquiring Minds, overconfidence can cause problems with meeting deadlines. But it can cause far more trouble by having a strong adverse effect on people’s financial health. Overconfidence often persuades people that they are in better financial shape than they actually are. It can also lead to bad investment and spending decisions. For example, nonprofessional investors who engage in a lot of speculative investing—

Unrealistic Expectations About Future Behavior Another form of overconfidence is being overly optimistic about your future behavior: tomorrow you’ll study, tomorrow you’ll give up ice cream, tomorrow you’ll spend less and save more, and so on. Of course, as we all know, when tomorrow arrives, it’s still just as hard to study or give up something that you like as it is right now.

Strategies that keep a person on the straight-

Mental accounting is the habit of mentally assigning dollars to different accounts so that some dollars are worth more than others.

Counting Dollars Unequally If you tend to spend more when you pay with a credit card than when you pay with cash, particularly if you tend to splurge, then you are very likely engaging in mental accounting. This is the habit of mentally assigning dollars to different accounts, making some dollars worth more than others.

By spending more with a credit card, you are in effect treating dollars in your wallet as more valuable than dollars on your credit card balance, although in reality they count equally in your budget.

Credit card overuse is the most recognizable form of mental accounting. However, there are other forms as well, such as splurging after receiving a windfall, like an unexpected inheritance, or overspending at sales, buying something that seemed like a great bargain that you later regretted. It’s the failure to understand that, regardless of the form it comes in, a dollar is a dollar.

Loss aversion is an oversensitivity to loss, leading to unwillingness to recognize a loss and move on.

Loss Aversion Loss aversion is an oversensitivity to loss, leading to an unwillingness to recognize a loss and move on. In fact, in the lingo of the financial markets, “selling discipline”—being able and willing to quickly acknowledge when a stock you’ve bought is a loser and sell it—

Many investors, though, are reluctant to acknowledge that they’ve lost money on a stock and won’t make it back. Although it’s rational to sell the stock at that point and redeploy the remaining funds, most people find it so painful to admit a loss that they avoid selling for much longer than they should. According to Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, most people feel the misery of losing $100 about twice as keenly as they feel the pleasure of gaining $100.

Loss aversion can help explain why sunk costs are so hard to ignore: ignoring a sunk cost means recognizing that the money you spent is unrecoverable and therefore lost.

The status quo bias is the tendency to avoid making a decision and sticking with the status quo.

Status Quo Bias Another irrational behavior is status quo bias, the tendency to avoid making a decision altogether. A well-

If everyone behaved rationally, then the proportion of employees enrolled in 401(k) accounts at opt-

Why do people exhibit status quo bias? Some claim it’s a form of “decision paralysis”: when given many options, people find it harder to make a decision. Others claim it’s due to loss aversion and the fear of regret, to thinking that “if I do nothing, then I won’t have to regret my choice.” Irrational, yes. But not altogether surprising. However, rational people know that, in the end, the act of not making a choice is still a choice.

Rational Models for Irrational People?

So why do economists still use models based on rational behavior when people are at times manifestly irrational? For one thing, models based on rational behavior still provide robust predictions about how people behave in most markets. For example, the great majority of farmers will use less fertilizer when it becomes more expensive—

Another explanation is that sometimes market forces can compel people to behave more rationally over time. For example, if you are a small-

Finally, economists depend on the assumption of rationality for the simple but fundamental reason that it makes modeling so much simpler. Remember that models are built on generalizations, and it’s much harder to extrapolate from messy, irrational behavior. Even behavioral economists, in their research, search for predictably irrational behavior in an attempt to build better models of how people behave. Clearly, there is an ongoing dialogue between behavioral economists and the rest of the economics profession, and economics itself has been irrevocably changed by it.

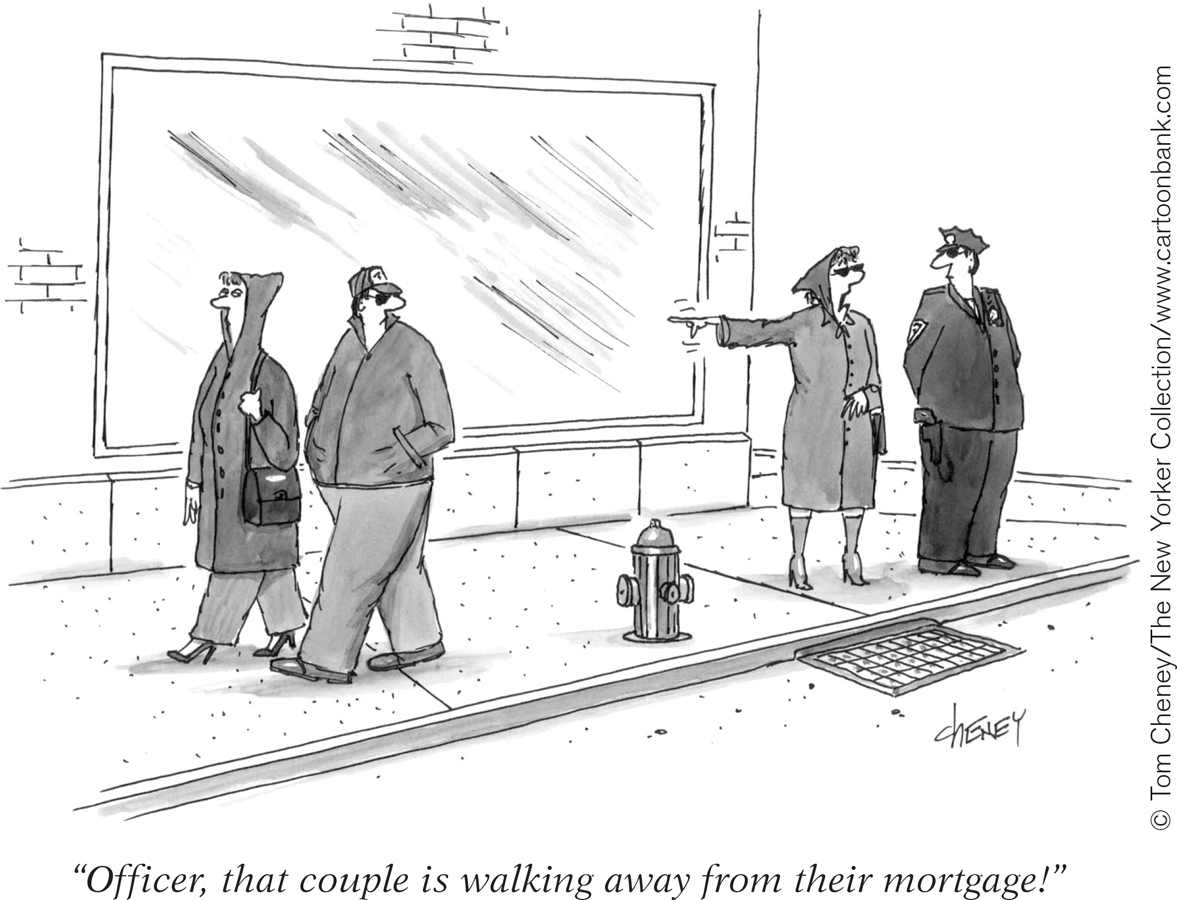

ECONOMICS in Action: “The Jingle Mail Blues”

“The Jingle Mail Blues”

It’s called jingle mail—

To default on a mortgage—

What happened? After decades of huge increases, house prices began a precipitous fall in 2008, known as the Great American Housing Bust. Prices dropped so much that a significant proportion of homeowners found their homes “underwater”—they owed more on their homes than the homes were worth. And with house prices projected to stay depressed for several years, possibly a decade, there appeared to be little chance that an underwater house would recover its value enough in the foreseeable future to move “abovewater.”

Many homeowners suffered a major loss. They lost their down payment, money spent on repairs and renovation, moving expenses, and so on. And because they were paying a mortgage that was greater than the house was now worth, they found they could rent a comparable dwelling for less than their monthly mortgage payments. In the words of a Florida resident, who paid $215,000 for an apartment in Miami where similar units were now selling for $90,000, “There is no financial sense in staying.”

Realizing their losses were sunk costs, underwater homeowners walked away. Perhaps they hadn’t made the best economic decision when purchasing their houses, but in leaving them showed impeccable economic logic.

Quick Review

Behavioral economics combines economic modeling with insights from human psychology.

Rational behavior leads to the outcome a person most prefers. Bounded rationality, risk aversion, and concerns about fairness are reasons why people might prefer outcomes with worse economic payoffs.

Irrational behavior occurs because of misperceptions of opportunity costs, overconfidence, mental accounting, and unrealistic expectations about the future. Loss aversion and status quo bias can also lead to choices that leave people worse off than they would be if they chose another available option.

9-4

9-

Question 9.8

Which of the types of irrational behavior are suggested by the following events?

Although the housing market has fallen and Jenny wants to move, she refuses to sell her house for any amount less than what she paid for it.

Jenny is exhibiting loss aversion. She has an oversensitivity to loss, leading to an unwillingness to recognize a loss and move on.Dan worked more overtime hours last week than he had expected. Although he is strapped for cash, he spends his unexpected overtime earnings on a weekend getaway rather than trying to pay down his student loan.

Dan is doing mental accounting. Dollars from his unexpected overtime earnings are worth less—spent on a weekend getaway—than the dollars earned from his regular hours that he uses to pay down his student loan.Carol has just started her first job and deliberately decided to opt out of the company’s savings plan. Her reasoning is that she is very young and there is plenty of time in the future to start saving. Why not enjoy life now?

Carol may have unrealistic expectations of future behavior. Even if she does not want to participate in the plan now, she should find a way to commit to participating at a later date.Jeremy’s company requires employees to download and fill out a form if they want to participate in the company-

sponsored savings plan. One year after starting the job, Jeremy had still not submitted the form needed to participate in the plan. Jeremy is showing signs of status quo bias. He is avoiding making a decision altogether; in other words, he is sticking with the status quo.

Question 9.9

How would you determine whether a decision you made was rational or irrational?

You would determine whether a decision was rational or irrational by first accurately accounting for all the costs and benefits of the decision. In particular, you must accurately measure all opportunity costs. Then calculate the economic payoff of the decision relative to the next best alternative. If you would still make the same choice after this comparison, then you have made a rational choice. If not, then the choice was irrational.

Solutions appear at back of book.

J. C. Penney’s One-Price Strategy Upsets Its Customers

In early 2013, the department store chain J. C. Penney unceremoniously dumped its recently hired chief executive, Ron Johnson. The action followed a disastrous 2012 for the company, in which sales dropped 25% to $13 billion. And it was a humbling defeat for Mr. Johnson’s strategy of “everyday” low prices, implemented in early 2012.

A year before the one-

So the new strategy seemed like a no-

The company reaped benefits from the strategy in the form of cost-

But, there were problems with this pricing strategy as well. Just how low the prices were wasn’t clear. “Trust us,” was the message J. C. Penney communicated to its shoppers, “We will give you a fair deal.” In addition, unlike Walmart, Penney did not offer to match competitors’ prices, and it could not depend on making up for tiny per-

Mr. Johnson’s strategy clearly alienated Tracie Fobes, who runs Penny Pinchin’ Mom, a blog about couponing strategies, who said, “… seeing that something is marked down 20% off, then being able to hand over the coupon to save, it just entices me.”

So with Johnson’s departure, J. C. Penney backtracked and began offering coupons and weekly sales again. And the store assistants went back to work, marking items up in order to then immediately mark them down.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 9.10

Give an example of a type of rational decision making illustrated by this case and explain your choice.

Give an example of a type of rational decision making illustrated by this case and explain your choice.Question 9.11

Give an example of a type of irrational decision making illustrated by this case and explain your choice.

Give an example of a type of irrational decision making illustrated by this case and explain your choice.Question 9.12

What purpose does Walmart’s price-

match guarantee serve? What do you predict would happen if it dropped this policy? Would you predict its competitors— say, the local supermarket or K- Mart— would adopt the same policy? What purpose does Walmart’s price-match guarantee serve? What do you predict would happen if it dropped this policy? Would you predict its competitors— say, the local supermarket or K- Mart— would adopt the same policy?