1.3 55Long-Run Growth Policy

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

Why growth rates vary in different regions of the world

Why growth rates vary in different regions of the world

What the convergence hypothesis predicts

What the convergence hypothesis predicts

Why Growth Rates Differ

In 1820, Mexico had somewhat higher real GDP per capita than Japan. Today, Japan has higher real GDP per capita than most European nations and Mexico is a poor country, though by no means among the poorest. The difference? Over the long run—

As this example illustrates, even small differences in growth rates have large consequences over the long run. So why do growth rates differ across countries and across periods of time?

Explaining Differences in Growth Rates

As one might expect, economies with rapid growth tend to add physical capital, increase their human capital, or experience rapid technological progress. Striking economic success stories, like Japan in the 1950s and 1960s or China today, tend to be countries that do all three:

- Rapidly add to their physical capital through high savings and investment spending

- Upgrade their educational level

- Make fast technological progress.

Evidence also points to the importance of government policies, property rights, political stability, and good governance in fostering the sources of growth.

Savings and Investment SpendingOne reason for differences in growth rates between countries is that some countries are increasing their stock of physical capital much more rapidly than others, through high rates of investment spending. In the 1960s, Japan was the fastest-

Today, China is the fastest-

Where does the money for high investment spending come from? From savings. Investment spending must be paid for either out of savings from domestic households or by savings from foreign households—

Foreign capital has played an important role in the long-

EducationJust as countries differ substantially in the rate at which they add to their physical capital, there have been large differences in the rate at which countries add to their human capital through education.

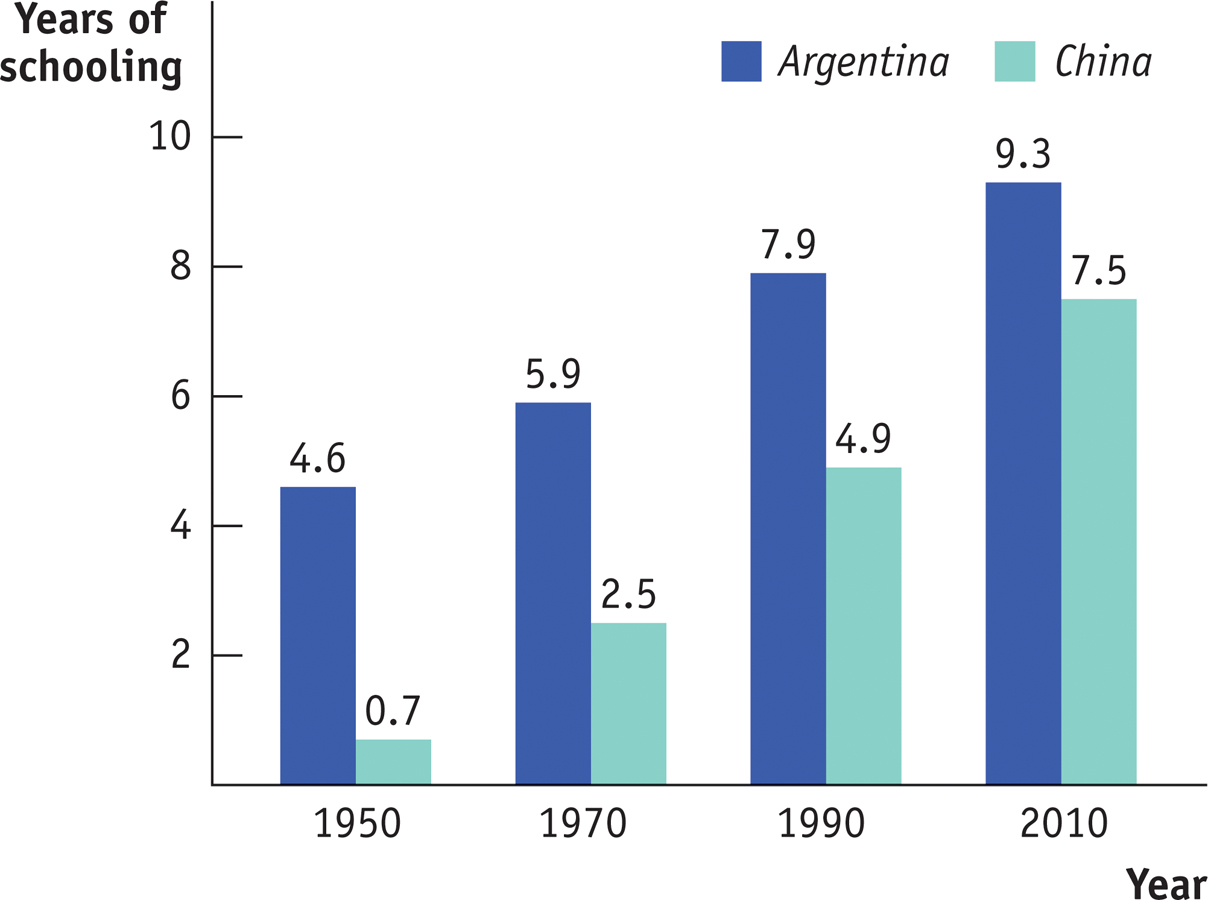

A case in point is the comparison between Argentina and China. In both countries the average educational level has risen steadily over time, but it has risen much faster in China. Figure 55-1 shows the average years of education of adults in China, which we have highlighted as a spectacular example of long-

As of 2010, the average educational level in China was still slightly below that in Argentina—

Research and DevelopmentThe advance of technology is a key force behind economic growth. What drives technological progress?

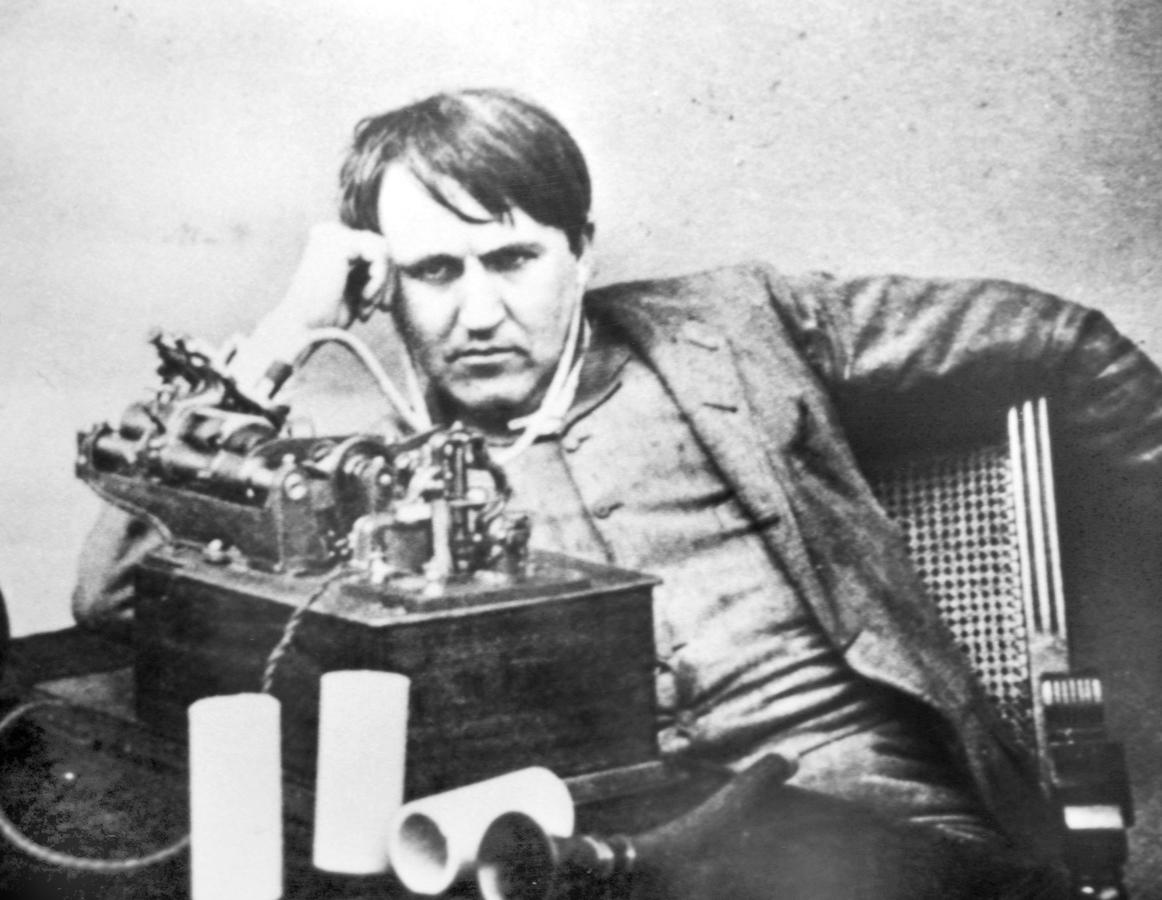

Scientific advances make new technologies possible. To take the most spectacular example in today’s world, the semiconductor chip—

But science alone is not enough: scientific knowledge must be translated into useful products and processes. And that often requires devoting a lot of resources to research and development, or R&D, spending to create new technologies and apply them to practical use.

Research and development, or R&D, is spending to create and implement new technologies.

Although some research and development is conducted by governments, much R&D is paid for by the private sector. The United States became the world’s leading economy in large part because American businesses were among the first to make systematic research and development a part of their operations.

The Role of Government in Promoting Economic Growth

Governments can play an important role in promoting—

Government policies can increase the economy’s growth rate through four main channels.

Roads, power lines, ports, information networks, and other underpinnings for economic activity are known as infrastructure.

1. Government Subsidies To InfrastructureGovernments play an important direct role in building infrastructure: roads, power lines, ports, information networks, and other large-

Ireland offers an example of the importance of government-

Poor infrastructure, such as a power grid that frequently fails and cuts off electricity, is a major obstacle to economic growth in many countries. To provide good infrastructure, an economy must not only be able to afford it, but it must also have the political discipline to maintain it.

Perhaps the most crucial infrastructure is something we, in an advanced country, rarely think about: basic public health measures in the form of a clean water supply and disease control. Poor health infrastructure is a major obstacle to economic growth in poor countries, especially those in Africa.

2. Government Subsidies To EducationIn contrast to physical capital, which is mainly created by private investment spending, much of an economy’s human capital is the result of government spending on education. Government pays for the great bulk of primary and secondary education. And it pays for a significant share of higher education: 75% of students attend public colleges and universities, and government significantly subsidizes research performed at private colleges and universities. As a result, differences in the rate at which countries add to their human capital largely reflect government policy. As we saw in Figure 55-1, educational levels in China are increasing much more rapidly than in Argentina. This isn’t because China is richer than Argentina; until recently, China was, on average, poorer than Argentina. Instead, it reflects the fact that the Chinese government has made education a high priority.

3. Government Subsidies To R&DTechnological progress is largely the result of private initiative. But in the more advanced countries, important R&D is done by government agencies as well. In the upcoming Economics in Action, we describe Brazil’s agricultural boom, which was made possible by government researchers who made discoveries that expanded the amount of arable land in Brazil, as well as developing new varieties of crops that flourish in Brazil’s climate.

4. Maintaining A Well-

If a country’s citizens trust their banks, they will place their savings in bank deposits, which the banks will then lend to their business customers. But if people don’t trust their banks, they will hoard gold or foreign currency, keeping their savings in safe deposit boxes or under the mattress, where it cannot be turned into productive investment spending. A well-

Governments can also create an environment that fosters economic growth by providing the following.

Protection Of Property RightsProperty rights are the rights of owners of valuable items to dispose of those items as they choose. A subset, intellectual property rights, are the rights of an innovator to accrue the rewards of her innovation.

The state of property rights generally, and intellectual property rights in particular, are important factors in explaining differences in growth rates across economies. Why? Because no one would bother to spend the effort and resources required to innovate if someone else could appropriate that innovation and capture the rewards. So, for innovation to flourish, intellectual property rights must receive protection.

Sometimes this is accomplished by the nature of the innovation: it may be too difficult or expensive to copy. But, generally, the government has to protect intellectual property rights. A patent is a government-

Political Stability and Good GovernanceThere’s not much point in investing in a business if rioting mobs are likely to destroy it, or saving your money if someone with political connections can steal it. Political stability and good governance (including the protection of property rights) are essential ingredients in fostering economic growth in the long run.

Long-

Americans take these preconditions for granted, but they are by no means guaranteed. Aside from the disruption caused by war or revolution, many countries find that their economic growth suffers due to corruption among the government officials who should be enforcing the law.

For example, until 1991 the Indian government imposed many bureaucratic restrictions on businesses, which often had to bribe government officials to get approval for even routine activities—

Even when the government isn’t corrupt, excessive government intervention can be a brake on economic growth. If large parts of the economy are supported by government subsidies, protected from imports, subject to unnecessary monopolization, or otherwise insulated from competition, productivity tends to suffer because of a lack of incentives.

THE BRAZILIAN BREADBASKET

A wry Brazilian joke says that “Brazil is the country of the future—

In recent years, however, Brazil’s economy has made a better showing, especially in agriculture. This success depends on exploiting a natural resource, the tropical savanna land known as the cerrado. Until a quarter-

The Brazilian Enterprise for Agricultural and Livestock Research, a government-

Also, until the 1980s, Brazilian international trade policies discouraged exports, as did an overvalued exchange rate that made the country’s goods more expensive to foreigners. After economic reform, investing in Brazilian agriculture became much more profitable and companies began putting in place the farm machinery, buildings, and other forms of physical capital needed to exploit the land.

What still limits Brazil’s growth? Infrastructure. According to a report in the New York Times, Brazilian farmers are “concerned about the lack of reliable highways, railways and barge routes, which adds to the cost of doing business.” Recognizing this, the Brazilian government is investing in infrastructure, and Brazilian agriculture is continuing to expand.

Success, Disappointment, and Failure

As we’ve seen, rates of long-

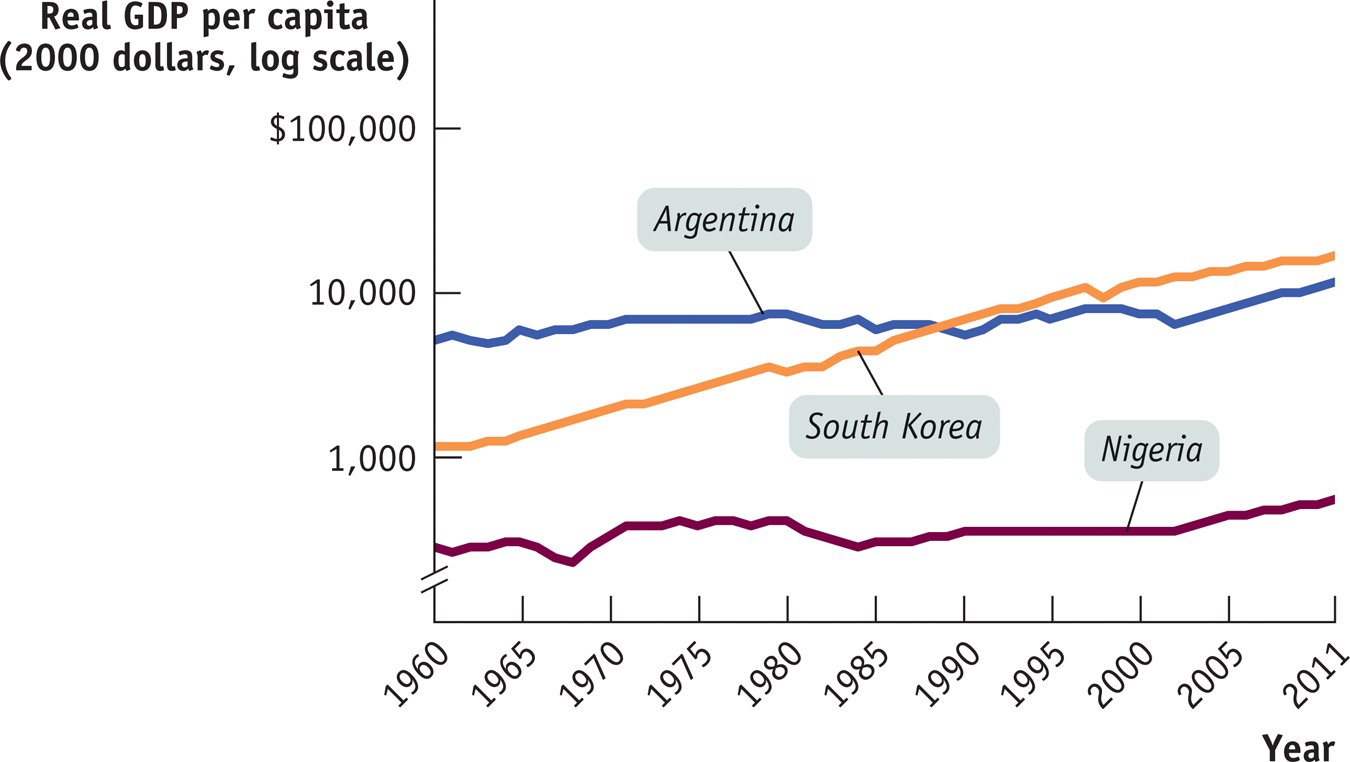

Figure 55-2 shows trends since 1960 in real GDP per capita for three countries: Argentina, Nigeria, and South Korea. We have chosen these countries because each is a particularly striking example of what has happened in its region.

South Korea’s amazing rise is part of a broad “economic miracle” in East Asia. Argentina’s slow progress, interrupted by repeated setbacks, is more or less typical of the disappointing growth that has characterized much of Latin America. And Nigeria’s unhappy story until very recently—

East Asia’s Miracle

In 1960 South Korea was a very poor country. In fact, in 1960 its real GDP per capita was lower than that of India today. But, as you can see from Figure 55-2, beginning in the early 1960s South Korea began an extremely rapid economic ascent: real GDP per capita grew about 7% per year for more than 30 years. Today South Korea, though still somewhat poorer than Europe or the United States, looks very much like an economically advanced country.

South Korea’s economic growth is unprecedented in history: it took the country only 35 years to achieve growth that required centuries elsewhere. Yet South Korea is only part of a broader phenomenon, often referred to as the East Asian economic miracle. High growth rates first appeared in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore but then spread across the region, most notably to China. Since 1975, the whole region has increased real GDP per capita by 6% per year, more than three times America’s historical rate of growth.

How have the Asian countries achieved such high growth rates? The answer is that all of the sources of productivity growth have been firing on all cylinders. Very high savings rates, the percentage of GDP that is saved nationally in any given year, have allowed the countries to significantly increase the amount of physical capital per worker. Very good basic education has permitted a rapid improvement in human capital. And these countries have experienced substantial technological progress.

Why didn’t any economy achieve this kind of growth in the past? Most economic analysts think that East Asia’s growth spurt was possible because of its relative backwardness. That is, by the time that East Asian economies began to move into the modern world, they could benefit from adopting the technological advances that had been generated in technologically advanced countries such as the United States.

In 1900, the United States could not have moved quickly to a modern level of productivity because much of the technology that powers the modern economy, from jet planes to computers, hadn’t been invented yet. In 1970, South Korea probably still had lower labor productivity than the United States had in 1900, but it could rapidly upgrade its productivity by adopting technology that had been developed in the United States, Europe, and Japan over the previous century. This was aided by a huge investment in human capital through widespread schooling.

According to the convergence hypothesis, international differences in real GDP per capita tend to narrow over time.

The East Asian experience demonstrates that economic growth can be especially fast in countries that are playing catch-

Even before we get to that evidence, however, we can say right away that starting with a relatively low level of real GDP per capita is no guarantee of rapid growth, as the examples of Latin America and Africa demonstrate.

Latin America’s Disappointment

In 1900, Latin America was not considered an economically backward region. Natural resources, including both minerals and cultivatable land, were abundant. Some countries, notably Argentina, attracted millions of immigrants from Europe in search of a better life. Measures of real GDP per capita in Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil were comparable to those in economically advanced countries.

Since about 1920, however, growth in Latin America has been disappointing. As Figure 55-2 shows in the case of Argentina, growth has been disappointing for many decades, until 2000 when it finally began to increase. The fact that South Korea is now much richer than Argentina would have seemed inconceivable a few generations ago.

Why did Latin America stagnate? Comparisons with East Asian success stories suggest several factors.

- The rates of savings and investment spending in Latin America have been much lower than in East Asia, partly as a result of irresponsible government policy that has eroded savings through high inflation, bank failures, and other disruptions.

- Education—

especially broad basic education— has been underemphasized: even Latin American nations rich in natural resources often failed to channel that wealth into their educational systems. - Political instability, leading to irresponsible economic policies, has taken a toll.

In the 1980s, many economists came to believe that Latin America was suffering from excessive government intervention in markets. They recommended opening the economies to imports, selling off government-

So far, however, only one Latin American nation, Chile, has achieved sustained rapid growth. It now seems that pulling off an economic miracle is harder than it looks. Although, in recent years Brazil and Argentina have seen their growth rates increase significantly as they exported large amounts of commodities to the advanced countries and rapidly developing China.

Africa’s Troubles and Promise

Africa south of the Sahara is home to about 910 million people, more than 2 ½ times the population of the United States. On average, they are very poor, nowhere close to U.S. living standards 100 or even 200 years ago. And economic progress has been both slow and uneven, as the example of Nigeria, the most populous nation in the region, suggests.

In fact, real GDP per capita in sub-

This is a very disheartening story. What explains it? Several factors are probably crucial. Perhaps first and foremost is the problem of political instability. In the years since 1975, large parts of Africa have experienced savage civil wars (often with outside powers backing rival sides) that have killed millions of people and made productive investment spending impossible. The threat of war and general anarchy has also inhibited other important preconditions for growth, such as education and provision of necessary infrastructure.

Property rights are also a major problem. The lack of legal safeguards means that property owners are often subject to extortion because of government corruption, making them averse to owning property or improving it. This is especially damaging in a very poor country.

But not all economists see political instability and government corruption as the leading causes of underdevelopment in Africa; some believe the opposite. They argue that Africa is politically unstable because Africa is poor. And Africa’s poverty, they go on to claim, stems from its extremely unfavorable geographic conditions—

They also highlight the importance of health problems in Africa. In poor countries, worker productivity is often severely hampered by malnutrition and disease. In particular, tropical diseases such as malaria can only be controlled with an effective public health infrastructure, something that is lacking in much of Africa.

Although the example of African countries represents a warning that long-

In 2012, real GDP per capita growth rates averaged around 5.5% across sub-

ARE ECONOMIES CONVERGING?

In the 1950s, much of Europe seemed quaint and backward to American visitors, and Japan seemed very poor. Today, a visitor to Paris or Tokyo sees a city that looks about as rich as New York. Although real GDP per capita is still somewhat higher in the United States, the differences in the standards of living among the United States, Europe, and Japan are relatively small.

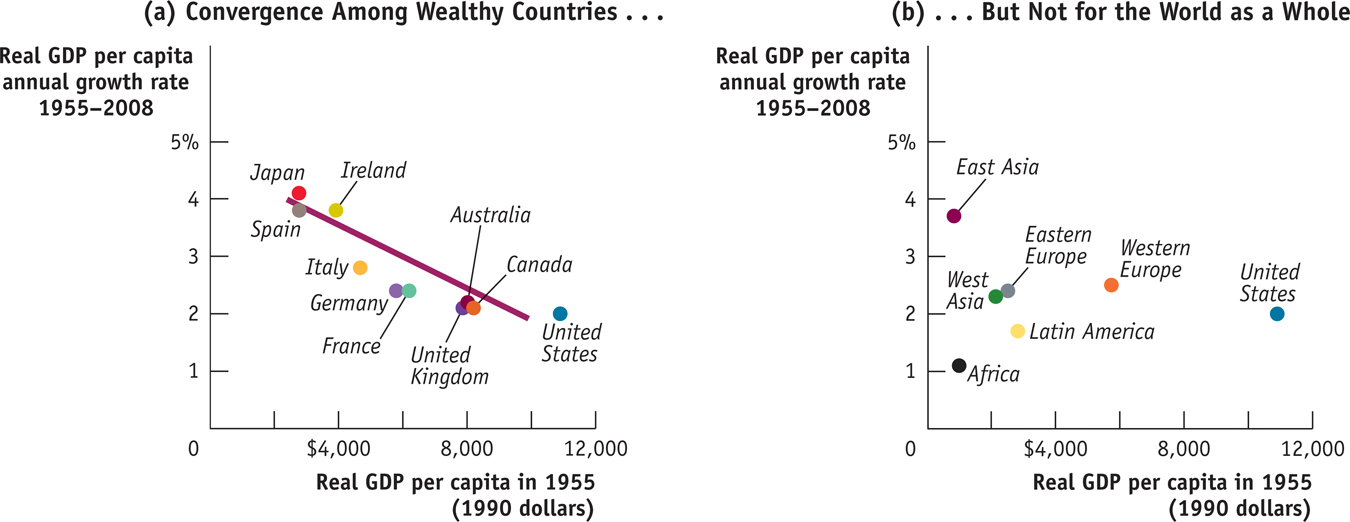

Many economists have argued that this convergence in living standards is normal; the convergence hypothesis says that relatively poor countries should have higher rates of growth of real GDP per capita than relatively rich countries. And if we look at today’s relatively well-

Panel (a) of Figure 55-3 shows data for a number of today’s wealthy economies measured in 1990 dollars. On the horizontal axis is real GDP per capita in 1955; on the vertical axis is the average annual growth rate of real GDP per capita from 1955 to 2008. There is a clear negative relationship as can be seen from the line fitted through the points. The United States was the richest country in this group in 1955 and had the slowest rate of growth. Japan and Spain were the poorest countries in 1955 and had the fastest rates of growth. These data suggest that the convergence hypothesis is true.

But economists who looked at similar data realized that these results depend on the countries selected. If you look at successful economies that have a high standard of living today, you find that real GDP per capita has largely converged in the last half-

So is the convergence hypothesis all wrong? No: economists still believe that countries with relatively low real GDP per capita tend to have higher rates of growth than countries with relatively high real GDP per capita, other things equal. But other things—

Because other factors differ, however, there is no clear tendency toward convergence in the world economy as a whole. Western Europe, North America, and parts of Asia are becoming more similar in real GDP per capita, but the gap between these regions and the rest of the world is growing.

55

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

Explain the link between a country’s growth rate, its investment spending as a percent of GDP, and its domestic savings.

A country that has high domestic savings is able to achieve a high rate of investment spending as a percentage of GDP. This, in turn, allows the country to achieve a high growth rate.Which of the following is the better predictor of a future high long-

run growth rate: a high standard of living today or high levels of savings and investment spending? Explain your answer. Although it is important in determining the growth rate for some countries (such as those of Western Europe), the initial level of GDP per capita isn’t the only factor. High rates of saving and investment appear to be better predictors of future growth than today’s standard of living.Some economists think the best way to help African countries is for wealthier countries to provide more funds for basic infrastructure. Others think this policy will have no long-

run effect unless African countries have the financial and political means to maintain this infrastructure. What policies would you suggest? The evidence suggests that both sets of factors matter: better infrastructure is important for growth, but so is political and financial stability. Policies should try to address both areas.

Multiple-

Question

What explains the different growth rates economies experience?

I. savings and investment spending

II. research and development

III. government policiesA. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following can lead to increases in physical capital in an economy?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

The following statement describes which area of the world? “This area has experienced growth rates unprecedented in history and now looks like an economically advanced country.”

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following is cited as an important factor preventing long-

run economic growth in Africa? A. B. C. D. E. Question

The convergence hypothesis

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

Question 1.2

Some economists think the high rates of growth of productivity achieved by many East Asian economies cannot be sustained. Why might they be right? What would have to happen for them to be wrong?