1.2 70Banking and Money Creation

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The role of banks in the economy

The role of banks in the economy

The reasons for and types of banking regulation

The reasons for and types of banking regulation

How banks create money

How banks create money

The Monetary Role of Banks

A little less than half of M1, the narrowest definition of the money supply, consists of currency in circulation—

What Banks Do

A bank is a financial intermediary that uses liquid assets in the form of bank deposits to finance the illiquid investments of borrowers. Banks can create liquidity because it isn’t necessary for a bank to keep all of the funds deposited with it in the form of highly liquid assets. Except in the case of a bank run—which we’ll get to shortly—

Bank reserves are the currency banks hold in their vaults plus their deposits at the Federal Reserve.

Banks can’t, however, lend out all the funds placed in their hands by depositors because they have to satisfy any depositor who wants to withdraw his or her funds. In order to meet these demands, a bank must keep substantial quantities of liquid assets on hand. In the modern U.S. banking system, these assets take the form either of currency in the bank’s vault or deposits held in the bank’s own account at the Federal Reserve. The latter can be converted into currency more or less instantly. Currency in bank vaults and bank deposits held at the Federal Reserve are called bank reserves. Because bank reserves are in bank vaults and at the Federal Reserve, not held by the public, they are not part of currency in circulation.

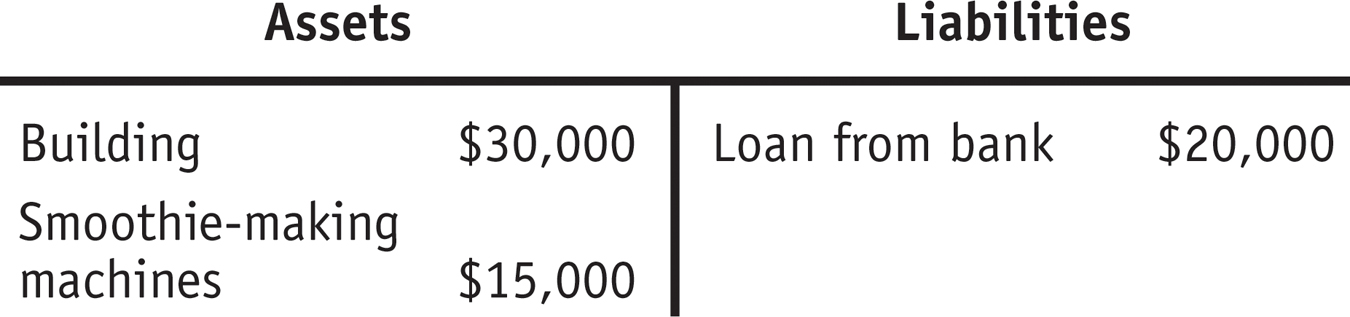

A T-

To understand the role of banks in determining the money supply, we start by introducing a simple tool for analyzing a bank’s financial position: a T-

Figure 70-1 shows the T-

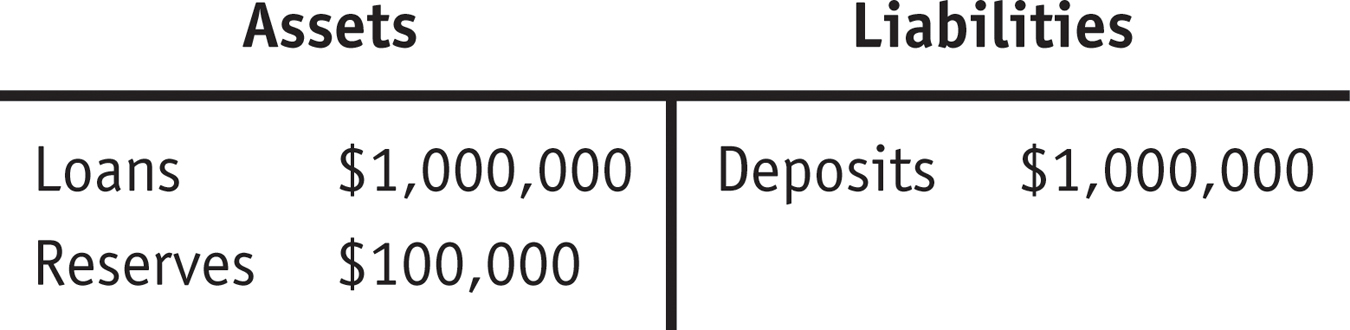

Samantha’s Smoothies is an ordinary, nonbank business. Now let’s look at the T-

Figure 70-2 shows First Street Bank’s financial position. The loans First Street Bank has made are on the left side because they’re assets: they represent funds that those who have borrowed from the bank are expected to repay. The bank’s only other assets, in this simplified example, are its reserves, which, as we’ve learned, can take the form either of cash in the bank’s vault or deposits at the Federal Reserve. On the right side we show the bank’s liabilities, which in this example consist entirely of deposits made by customers at First Street Bank. These are liabilities because they represent funds that must ultimately be repaid to depositors.

Notice, by the way, that in this example First Street Bank’s assets are larger than its liabilities. That’s the way it’s supposed to be! In fact, as we’ll see shortly, banks are required by law to maintain assets larger by a specific percentage than their liabilities.

The reserve ratio is the fraction of bank deposits that a bank holds as reserves.

In this example, First Street Bank holds reserves equal to 10% of its customers’ bank deposits. The fraction of bank deposits that a bank holds as reserves is its reserve ratio.

The required reserve ratio is the smallest fraction of deposits that the Federal Reserve allows banks to hold.

In the modern American system, the Federal Reserve—

The Problem of Bank Runs

A bank can lend out most of the funds deposited in its care because in normal times only a small fraction of its depositors want to withdraw their funds on any given day. But what would happen if, for some reason, all or at least a large fraction of its depositors did try to withdraw their funds during a short period of time, such as a couple of days?

If a significant share of its depositors demanded their money back at the same time, the bank wouldn’t be able to raise enough cash to meet those demands. The reason is that banks convert most of their depositors’ funds into loans made to borrowers; that’s how banks earn revenue—

Bank loans, however, are illiquid: they can’t easily be converted into cash on short notice. To see why, imagine that First Street Bank has lent $100,000 to Drive-

The upshot is that if a significant number of First Street Bank’s depositors suddenly decided to withdraw their funds, the bank’s efforts to raise the necessary cash quickly would force it to sell off its assets very cheaply. Inevitably, this leads to a bank failure: the bank would be unable to pay off its depositors in full.

What might start this whole process? That is, what might lead First Street Bank’s depositors to rush to pull their money out? A plausible answer is a spreading rumor that the bank is in financial trouble. Even if depositors aren’t sure the rumor is true, they are likely to play it safe and get their money out while they still can. And it gets worse: a depositor who simply thinks that other depositors are going to panic and try to get their money out will realize that this could “break the bank.” So he or she joins the rush. In other words, fear about a bank’s financial condition can be a self-

A bank run is a phenomenon in which many of a bank’s depositors try to withdraw their funds due to fears of a bank failure.

A bank run is a phenomenon in which many of a bank’s depositors try to withdraw their funds due to fears of a bank failure. Bank runs aren’t bad only for the bank in question and its depositors. Historically, they have often proved contagious, with a run on one bank leading to a loss of faith in other banks, causing additional bank runs. The upcoming Economics in Action describes an actual case of just such a contagion, the wave of bank runs that swept across the United States in the early 1930s. In response to that experience and similar experiences in other countries, most modern governments established a system of bank regulations, which we’ll look at next.

IT’S A WONDERFUL BANKING SYSTEM

Next Christmastime, it’s a sure thing that at least one TV channel will show the 1946 film It’s a Wonderful Life, featuring Jimmy Stewart as George Bailey. The movie’s climactic scene is a run on Bailey’s bank, as fearful depositors rush to take their funds out.

When the movie was made, such scenes were still fresh in Americans’ memories. There was a wave of bank runs in late 1930, a second wave in the spring of 1931, and a third wave in early 1933. By the end, more than a third of the nation’s banks had failed. To bring the panic to an end, in 1933, the newly inaugurated president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, closed all banks for a week to give bank regulators time to shut down unhealthy banks and certify healthy ones.

Since then, regulation has protected the United States and other wealthy countries against most bank runs. In fact, the scene in It’s a Wonderful Life was already out of date when the movie was made. But the last 15 years have seen several waves of bank runs in developing countries. For example, bank runs played a role in an economic crisis that swept Southeast Asia in 1997–

Notice that we said “most bank runs.” There are some limits on deposit insurance. As a result, there can still be a rush to pull money out of a bank perceived as troubled. In fact, that’s exactly what happened to IndyMac, a California-

Bank Regulation

Deposit insurance guarantees that a bank’s depositors will be paid even if the bank can’t come up with the funds, up to a maximum amount per account.

Should you worry about losing money in the United States due to a bank run? No. After the banking crises of the 1930s, the United States and most other countries put into place a system designed to protect depositors and the economy as a whole against bank runs. This system has three main features: deposit insurance, capital requirements, and reserve requirements. In addition, banks have access to the discount window, a source of cash when it’s needed.

1. Deposit InsuranceAlmost all banks in the United States advertise themselves as a “member of the FDIC”—the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. The FDIC provides deposit insurance, a guarantee that depositors will be paid even if the bank can’t come up with the funds, up to a maximum amount per account. Currently, the FDIC guarantees the first $250,000 per depositer, per insured bank.

Deposit insurance doesn’t just protect depositors if a bank actually fails. The insurance also eliminates the main reason for bank runs: since depositors know their funds are safe even if a bank fails, they have no incentive to rush to pull them out because of a rumor that the bank is in trouble.

2. Capital RequirementsDeposit insurance, although it protects the banking system against bank runs, creates a well-

To reduce the incentive for excessive risk-

Reserve requirements are rules set by the Federal Reserve that determine the required reserve ratio for banks.

3. Reserve RequirementsAnother regulation used to reduce the risk of bank runs is reserve requirements, rules set by the Federal Reserve that specify the minimum reserve ratio for banks. For example, in the United States, the required reserve ratio for checkable bank deposits is 10%.

The discount window is an arrangement in which the Federal Reserve stands ready to lend money to banks.

4. The Discount WindowOne final protection against bank runs is the fact that the Federal Reserve, which we’ll discuss more thoroughly later, stands ready to lend money to banks in trouble, an arrangement known as the discount window. The ability to borrow money means a bank can avoid being forced to sell its assets at fire-

Determining the Money Supply

Without banks, there would be no checkable deposits, and so the quantity of currency in circulation would equal the money supply. In that case, the money supply would be determined solely by whoever controls government minting and printing presses.

But banks do exist, and through their creation of checkable bank deposits, they affect the money supply in two ways.

- Banks remove some currency from circulation: dollar bills that are sitting in bank vaults, as opposed to sitting in people’s wallets, aren’t part of the money supply.

- Much more importantly, banks create money by accepting deposits and making loans—

that is, they make the money supply larger than just the value of currency in circulation.

Next we cover how banks create money and what determines the amount of money they create.

How Banks Create Money

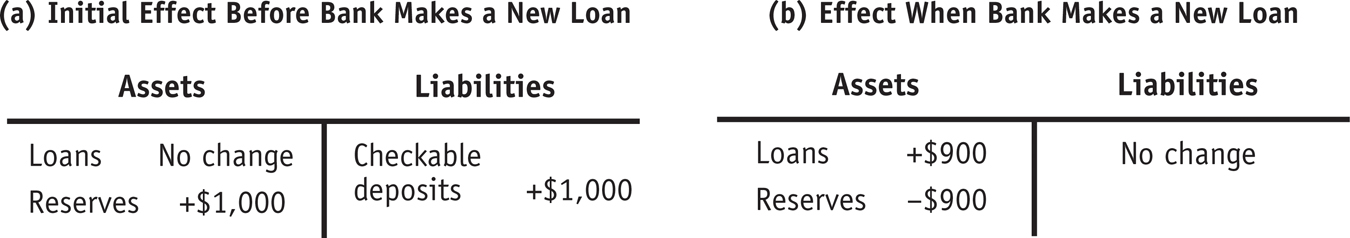

To see how banks create money, let’s examine what happens when someone decides to deposit currency in a bank. Consider the example of Silas, a miser, who keeps a shoebox full of cash under his bed. Suppose Silas realizes that it would be safer, as well as more convenient, to deposit that cash in the bank and to use his debit card when shopping. Assume that he deposits $1,000 into a checkable account at First Street Bank. What effect will Silas’s actions have on the money supply?

Panel (a) of Figure 70-3 shows the initial effect of his deposit. First Street Bank credits Silas with $1,000 in his account, so the economy’s checkable bank deposits rise by $1,000. Meanwhile, Silas’s cash goes into the vault, raising First Street Bank’s reserves by $1,000 as well.

This initial transaction has no effect on the money supply. Currency in circulation, part of the money supply, falls by $1,000; checkable bank deposits, also part of the money supply, rise by the same amount.

But this is not the end of the story because First Street Bank can now lend out part of Silas’s deposit. Assume that it holds 10% of Silas’s deposit—

So by putting $900 of Silas’s cash back into circulation by lending it to Mary, First Street Bank has, in fact, increased the money supply. That is, the sum of currency in circulation and checkable bank deposits has risen by $900 compared to what it had been when Silas’s cash was still under his bed. Although Silas is still the owner of $1,000, now in the form of a checkable deposit, Mary has the use of $900 in cash from her borrowings.

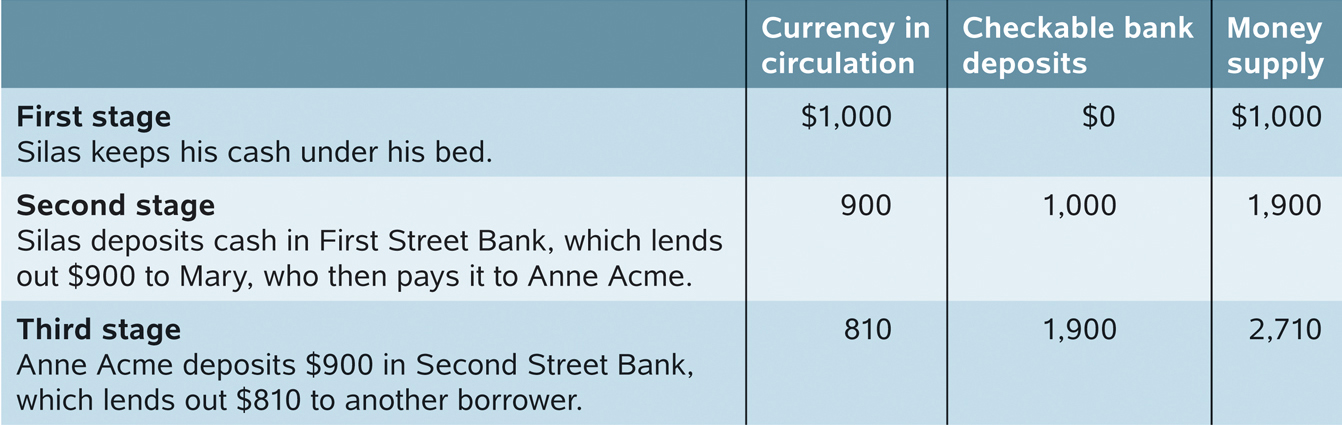

And this may not be the end of the story. Suppose that Mary uses her cash to buy a television and a tablet from Acme Electronics. What does Anne Acme, the store’s owner, do with the cash? If she holds on to it, the money supply doesn’t increase any further. But suppose she deposits the $900 into a checkable bank deposit—

Assume that Second Street Bank, like First Street Bank, keeps 10% of any bank deposit in reserves and lends out the rest. Then it will keep $90 in reserves and lend out $810 of Anne’s deposit to another borrower, further increasing the money supply.

Table 70-1 shows the process of money creation we have described so far. At first the money supply consists only of Silas’s $1,000. After he deposits the cash into a checkable bank deposit and the bank makes a loan, the money supply rises to $1,900. After the second deposit and the second loan, the money supply rises to $2,710. And the process will, of course, continue from there. (Although we have considered the case in which Silas places his cash in a checkable bank deposit, the results would be the same if he put it into any type of near-

70-1

How Banks Create Money

This process of money creation may sound familiar. Recall the multiplier process that we described earlier: an initial increase in real GDP leads to a rise in consumer spending, which leads to a further rise in real GDP, which leads to a further rise in consumer spending, and so on. What we have here is another kind of multiplier—

Reserves, Bank Deposits, and the Money Multiplier

In tracing out the effect of Silas’s deposit in Table 70-1, we assumed that the funds a bank lends out always end up being deposited either in the same bank or in another bank—

In reality, some of these loaned funds may be held by borrowers in their wallets and not deposited in a bank, meaning that some of the loaned amount “leaks” out of the banking system. Such leaks reduce the size of the money multiplier, just as leaks of real income into savings reduce the size of the real GDP multiplier. (Bear in mind, however, that the “leak” here comes from the fact that borrowers keep some of their funds in currency, rather than the fact that consumers save some of their income.)

Excess reserves are a bank’s reserves over and above its required reserves.

But let’s set that complication aside for a moment and consider how the money supply is determined in a “checkable-

Now suppose that for some reason a bank suddenly finds itself with $1,000 in excess reserves. What happens? The answer is that the bank will lend out that $1,000, which will end up as a checkable bank deposit somewhere in the banking system, launching a money multiplier process very similar to the process shown in Table 70-1.

In the first stage, the bank lends out its excess reserves of $1,000, which becomes a checkable bank deposit somewhere. The bank that receives the $1,000 deposit keeps 10%, or $100, as reserves and lends out the remaining 90%, or $900, which again becomes a checkable bank deposit somewhere. The bank receiving this $900 deposit again keeps 10%, which is $90, as reserves and lends out the remaining $810. The bank receiving this $810 keeps $81 in reserves and lends out the remaining $729, and so on.

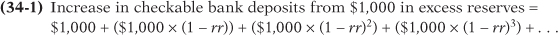

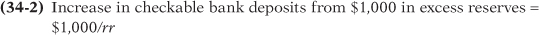

As a result of this process, the total increase in checkable bank deposits is equal to a sum that looks like:

$1,000 + $900 + $810 + $729 + …

We’ll use the symbol rr for the reserve ratio. More generally, the total increase in checkable bank deposits that is generated when a bank lends out $1,000 in excess reserves is the:

As we have seen, an infinite series of this form can be simplified to:

Given a reserve ratio of 10%, or 0.1, a $1,000 increase in excess reserves will increase the total value of checkable bank deposits by $1,000/0.1 = $10,000. In fact, in a checkable-

The Money Multiplier in Reality

In reality, the determination of the money supply is more complicated than our simple model suggests because it depends not only on the ratio of reserves to bank deposits but also on the fraction of the money supply that individuals choose to hold in the form of currency. In fact, we already saw this in our example of Silas depositing the cash under his bed: when he chose to hold a checkable bank deposit instead of currency, he set in motion an increase in the money supply.

The monetary base is the sum of currency in circulation and bank reserves.

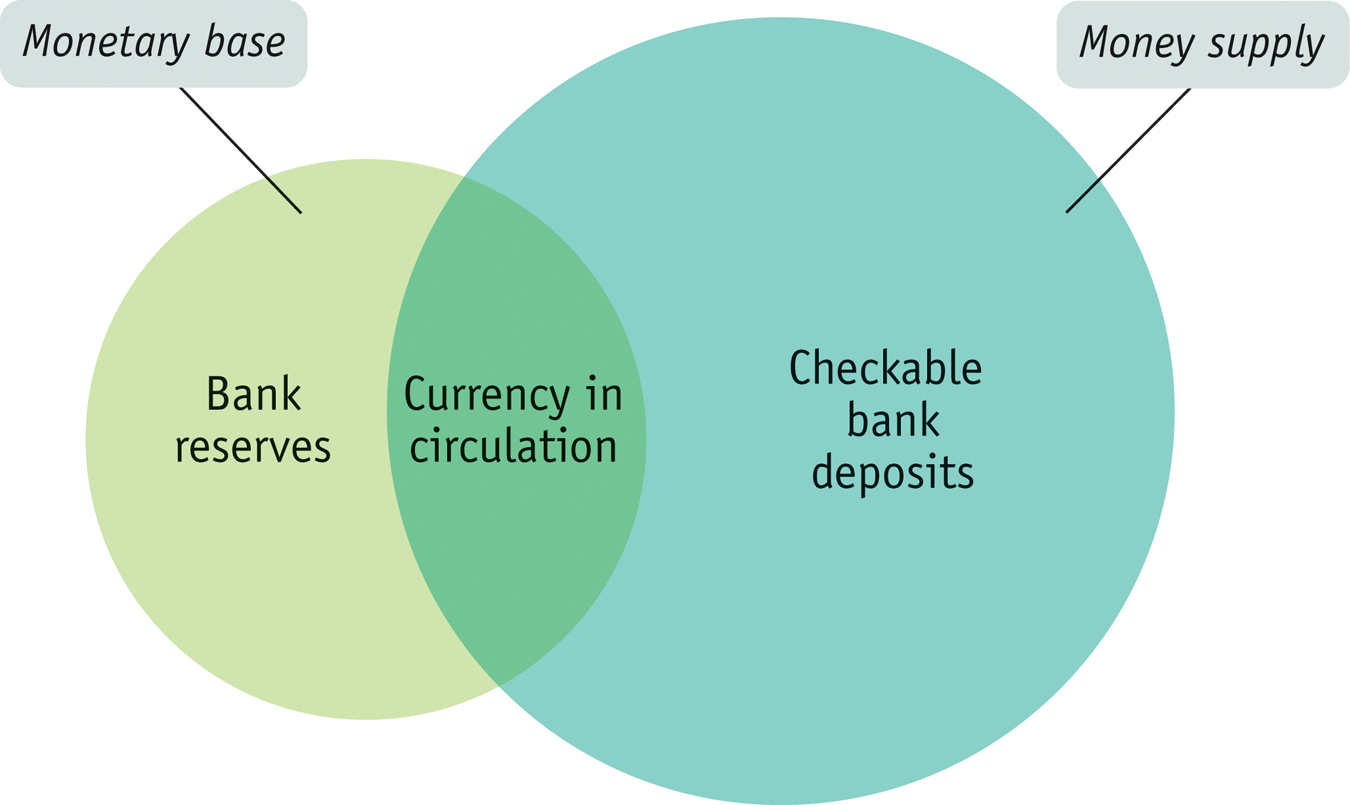

To define the money multiplier in practice, it’s important to recognize that the Federal Reserve controls the sum of bank reserves and currency in circulation, called the monetary base, but it does not control the allocation of that sum between bank reserves and currency in circulation. Consider Silas and his deposit one more time: by taking the cash from under his bed and depositing it in a bank, he reduces the quantity of currency in circulation but increases bank reserves by an equal amount—

The monetary base is different from the money supply in two ways.

- Bank reserves, which are part of the monetary base, aren’t considered part of the money supply. A $1 bill in someone’s wallet is considered money because it’s available for an individual to spend, but a $1 bill held as bank reserves in a bank vault or deposited at the Federal Reserve isn’t considered part of the money supply because it’s not available for spending.

- Checkable bank deposits, which are part of the money supply because they are available for spending, aren’t part of the monetary base.

Figure 70-4 shows the two concepts schematically. The circle on the left represents the monetary base, consisting of bank reserves plus currency in circulation. The circle on the right represents the money supply, consisting mainly of currency in circulation plus checkable or near-

The money multiplier is the ratio of the money supply to the monetary base.

Now we can formally define the money multiplier: it’s the ratio of the money supply to the monetary base. In normal times the money multiplier in the United States, using M1 as our measure of money, has fluctuated between 3.0 and 1.5. During the recession of 2007–

The reason the actual money multiplier is so small arises from the fact that people hold significant amounts of cash, and a dollar of currency in circulation, unlike a dollar in reserves, doesn’t support multiple dollars of the money supply. In fact, currency in circulation normally accounts for more than 90% of the monetary base. However, in April 2013, currency in circulation was $1,107 billion, compared with a monetary base of $3,061 billion—

Notice that earlier we said “in normal times.” As we’ll see in upcoming modules, a very abnormal situation developed after Lehman Brothers, a key financial institution, failed in September 2008. Banks, seeing few opportunities for safe, profitable lending, began parking large sums at the Federal Reserve in the form of deposits—

70

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

Suppose you are a depositor at First Street Bank. You hear a rumor that the bank has suffered serious losses on its loans. Every depositor knows that the rumor isn’t true, but each thinks that most other depositors believe the rumor. Why, in the absence of deposit insurance, could this lead to a bank run? How does deposit insurance change the situation?

Even though you know that the rumor about the bank is not true, you are concerned about other depositors pulling their money out of the bank. And you know that if enough other depositors pull their money out, the bank will fail. In that case, it is rational for you to pull your money out before the bank fails. All depositors will think like this, so even if they all know that the rumor is false, they may still rationally pull their money out, leading to a bank run. Deposit insurance leads depositors to worry less about the possibility of a bank run. Even if a bank fails, the FDIC will currently pay each depositor up to $250,000 per account. This will make you much less likely to pull your money out in response to a rumor. Since other depositors will think the same, there will be no bank run.A con artist has a great idea: he’ll open a bank without investing any capital and lend all the deposits at high interest rates to real estate developers. If the real estate market booms, the loans will be repaid and he’ll make high profits. If the real estate market goes bust, the loans won’t be repaid and the bank will fail—

but he will not lose any of his own wealth. How would modern bank regulation frustrate his scheme? The aspects of modern bank regulation that would frustrate this scheme are capital requirements and reserve requirements. Capital requirements mean that a bank has to have a certain amount of capital—the difference between its assets (loans plus reserves) and its liabilities (deposits). So the con artist could not open a bank without putting any of his own wealth in because his bank would need the required amount of capital—that is, it needs to hold more assets (loans plus reserves) than deposits. So the con artist would be at risk of losing his own wealth if his loans turn out badly.Assume that total reserves are equal to $200 and total checkable bank deposits are equal to $1,000. Also assume that the public does not hold any currency and banks hold no excess reserves. Now suppose that the required reserve ratio falls from 20% to 10%. Trace out how this leads to an expansion in bank deposits.

Since they have to hold only $100 in reserves, instead of $200, banks now lend out $100 of their reserves. Whoever borrows the $100 will deposit it in a bank (or spend it, and the recipient will deposit it in a bank), which will lend out $100 × (1 − rr) = $100 × 0.9 = $90. The borrowed $90 will likewise find its way into a bank, which will lend out $90 × 0.9 = $81, and so on. Overall, deposits will increase by $100/0.1 = $1,000.Take the example of Silas depositing his $1,000 in cash into First Street Bank and assume that the required reserve ratio is 10%. But now assume that each recipient of a bank loan keeps half the loan in cash and deposits the rest. Trace out the resulting expansion in the money supply through at least three rounds of deposits.

Silas puts $1,000 in the bank, of which the bank lends out $1,000 × (1 − rr) = $1,000 × 0.9 = $900. Whoever borrows the $900 will keep $450 in cash and deposit $450 in the bank. The bank will lend out $450 × 0.9 = $405. Whoever borrows the $405 will keep $202.50 in cash and deposit $202.50 in the bank. The bank will lend out $202.50 × 0.9 = $182.25, and so on. Overall this leads to an increase in deposits of $1,000 + $450 + $202.50 +… But it decreases the amount of currency in circulation: the amount of cash is reduced by the $1,000 Silas puts into the bank. This is offset, but not fully, by the amount of cash held by each borrower. The amount of currency in circulation therefore changes by −$1,000 + $450 + $202.50 +… The money supply therefore increases by the sum of the increase in deposits and the change in currency in circulation, which is $1,000 − $1,000 + $450 + $450 + $202.50 + $202.50 +… and so on.

Multiple-

Question

Bank reserves include which of the following?

I. currency in bank vaults

II. bank deposits held in accounts at the Federal Reserve

III. customer deposits in bank checking accountsA. B. C. D. E. Question

The fraction of bank deposits actually held as reserves is the

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Bank regulation includes which of the following?

I. deposit insurance

II. capital requirements

III. reserve requirementsA. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following changes would be the most likely to reduce the size of the money multiplier?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

The monetary base equals

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

Assume that the required reserve ratio is 5% to answer the following.

If a bank has deposits of $100,000 and holds $10,000 as reserves, how much are its excess reserves? Explain.

The bank must hold $5,000 as required reserves (5% of $100,000). It is holding $10,000, so $5,000 must be excess reserves.If a bank holds no excess reserves and it receives a new deposit of $1,000, how much of that $1,000 can the bank lend out and how much is the bank required to add to its reserves? Explain.

The bank must hold an additional $50 as reserves because that is the reserve requirement multiplied by the deposit: 5% of $1,000. The bank can lend out $950.By how much can an increase in excess reserves of $2,000 change the money supply in a checkable-

deposits- only system? Explain. The money multiplier is 1/0.05 = 20. An increase of $2,000 in excess reserves can increase the money supply by $2,000 × 20 = $40,000.