1.1 79Capital Flows and the Balance of Payments

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The meaning of the balance of payments accounts

The meaning of the balance of payments accounts

The determinants of international capital flows

The determinants of international capital flows

The Balance of Payments Accounts

In 2012, people living in the United States sold about $3.5 trillion worth of stuff to people living in other countries and bought about $3.5 trillion worth of stuff in return. What kind of stuff? All kinds. Residents of the United States (including employees of firms operating in the United States) sold airplanes, bonds, wheat, and many other items to residents of other countries. Residents of the United States bought cars, stocks, oil, and many other items from residents of other countries.

How can we keep track of these transactions? Earlier we learned that economists keep track of the domestic economy using the national income and product accounts. Economists keep track of international transactions using a different but related set of numbers, the balance of payments accounts.

Understanding the Balance of Payments

A country’s balance of payments accounts are a summary of the country’s transactions with other countries.

A country’s balance of payments accounts are a summary of the country’s transactions with other countries.

To understand the basic idea behind the balance of payments accounts, let’s consider a small-

- They made $100,000 by selling artichokes.

- They spent $70,000 on running the farm, including purchases of new farm machinery, and another $40,000 buying food, paying utility bills for their home, replacing their worn-

out car, and so on. - They received $500 in interest on their bank account but paid $10,000 in interest on their mortgage.

- They took out a new $25,000 loan to help pay for farm improvements but didn’t use all the money immediately. So they put the extra in the bank.

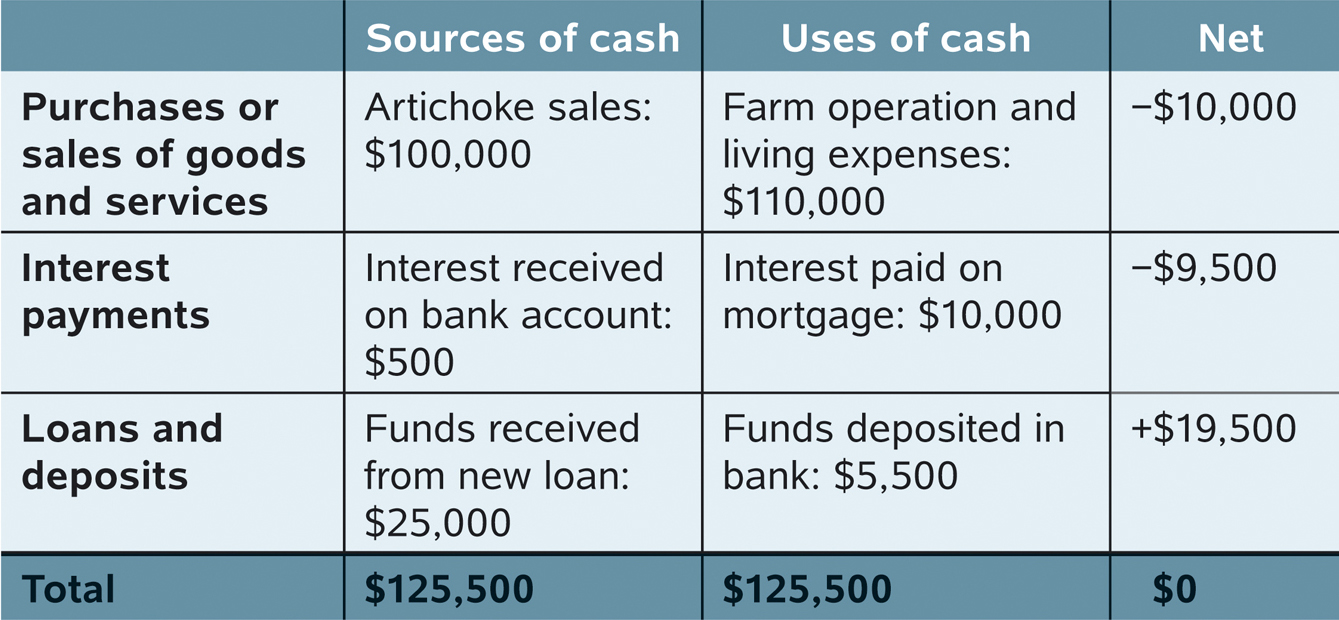

How could we summarize the Costas’ year? One way would be with a table like Table 79-1, which shows sources of cash coming in and money going out, characterized under a few broad headings.

79-1

The Costas’ Financial Year

The first row of Table 79-1 shows sales and purchases of goods and services: sales of artichokes; purchases of groceries, heating oil, that new car, and so on. The second row shows interest payments: the interest the Costas received from their bank account and the interest they paid on their mortgage. The third row shows cash coming in from new borrowing versus money deposited in the bank.

In each row we show the net inflow of cash from that type of transaction. So the net in the first row is −$10,000 because the Costas spent $10,000 more than they earned. The net in the second row is −$9,500, the difference between the interest the Costas received on their bank account and the interest they paid on the mortgage. The net in the third row is $19,500: the Costas brought in $25,000 with their new loan but put only $5,500 of that sum in the bank.

The last row shows the sum of cash coming in from all sources and the sum of all cash used. These sums are equal, by definition: every dollar has a source, and every dollar received gets used somewhere. (What if the Costas hid money under the mattress? Then that would be counted as another “use” of cash.)

A country’s balance of payments accounts summarize its transactions with the world using a table similar to the one we just used to summarize the Costas’ financial year.

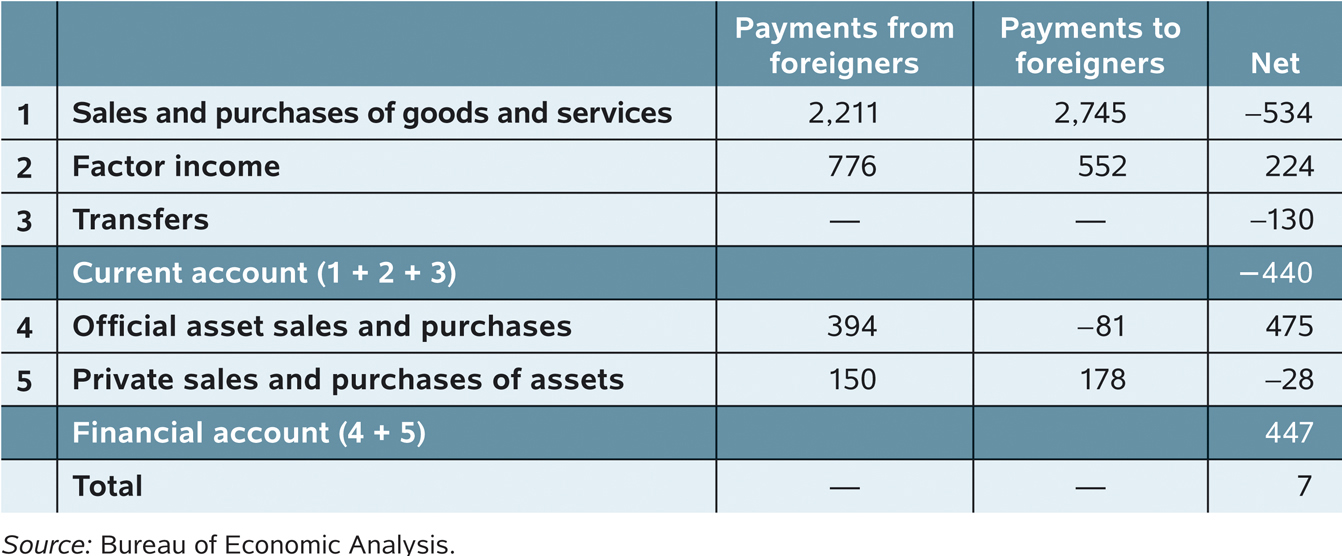

Table 79-2 on the next page shows a simplified version of the U.S. balance of payments accounts for 2012. Where the Costa family’s accounts show sources and uses of cash, the U.S. balance of payments accounts show payments from foreigners—

79-2

The U.S. Balance of Payments in 2012 (billions of dollars)

Row 1 of Table 79-2 shows payments that arise from sales and purchases of goods and services. For example, the value of U.S. wheat exports and the fees foreigners pay to U.S. consulting companies appear in the second column; the value of U.S. oil imports and the fees American companies pay to Indian call centers—

Row 2 shows factor income—payments for the use of factors of production owned by residents of other countries. Mostly this means investment income: interest paid on loans from overseas, the profits of foreign-

Row 3 shows international transfers—funds sent by residents of one country to residents of another. The main element here is the remittances that immigrants, such as the millions of Mexican-

The next two rows of Table 79-2 show payments resulting from sales and purchases of assets, broken down by who is doing the buying and selling. Row 4 shows transactions that involve governments or government agencies, mainly central banks. As we’ll learn later, in 2012 most of the U.S. sales in this category involved the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves by the central banks of China and oil-

In laying out Table 79-2, we have separated rows 1, 2, and 3 into one group and rows 4 and 5 into another. This reflects a fundamental difference in how these two groups of transactions affect the future.

When a U.S. resident sells a good, such as wheat, to a foreigner, that’s the end of the transaction. But a financial asset, such as a bond, is different. Remember, a bond is a promise to pay interest and principal in the future. So when a U.S. resident sells a bond to a foreigner, that sale creates a liability: the U.S. resident will have to pay interest and repay principal in the future. The balance of payments accounts distinguish between transactions that don’t create liabilities and those that do.

A country’s balance of payments on the current account, or the current account, is its balance of payments on goods and services plus net international transfer payments and factor income.

A country’s balance of payments on goods and services is the difference between its exports and its imports of both goods and services during a given period.

Transactions that don’t create liabilities are considered part of the balance of payments on the current account, often referred to simply as the current account: the balance of payments on goods and services plus factor income and net international transfer payments. The balance of row 1 of Table 79-2, −$534 billion, corresponds to the most important part of the current account: the balance of payments on goods and services, the difference between the value of exports and the value of imports during a given period.

The merchandise trade balance, or trade balance, is the difference between a country’s exports and imports of goods.

If you read news reports on the economy, you may well see references to another measure, the merchandise trade balance, sometimes referred to as the trade balance for short. This is the difference between a country’s exports and imports of goods alone—

A country’s balance of payments on the financial account, or simply the financial account, is the difference between its sales of assets to foreigners and its purchases of assets from foreigners during a given period.

The current account, as we’ve just learned, consists of international transactions that don’t create liabilities. Transactions that involve the sale or purchase of assets, and therefore do create future liabilities, are considered part of the balance of payments on the financial account, or the financial account for short. (Until a few years ago, economists often referred to the financial account as the capital account. We’ll use the modern term, but you may run across the older term.)

So how does it all add up? The first two unnumbered rows of Table 79-2 show the bottom lines: the overall U.S. current account and financial account for 2012. As you can see, in 2012, the United States ran a current account deficit: the amount it paid to foreigners for goods, services, factors, and transfers was greater than the amount it received. Simultaneously, it ran a financial account surplus: the value of the assets it sold to foreigners was greater than the value of the assets it bought from foreigners.

In the official data, the U.S. current account deficit and financial account surplus almost, but not quite, offset each other: the financial account surplus was $7 billion larger than the current account deficit. But that’s just a statistical error, reflecting the imperfection of official data. (And a $7 billion error when you’re measuring inflows and outflows of $3.5 trillion isn’t bad!) In fact, it’s a basic rule of balance of payments accounting that the current account and the financial account must sum to zero:

(79-

or

CA = −FA

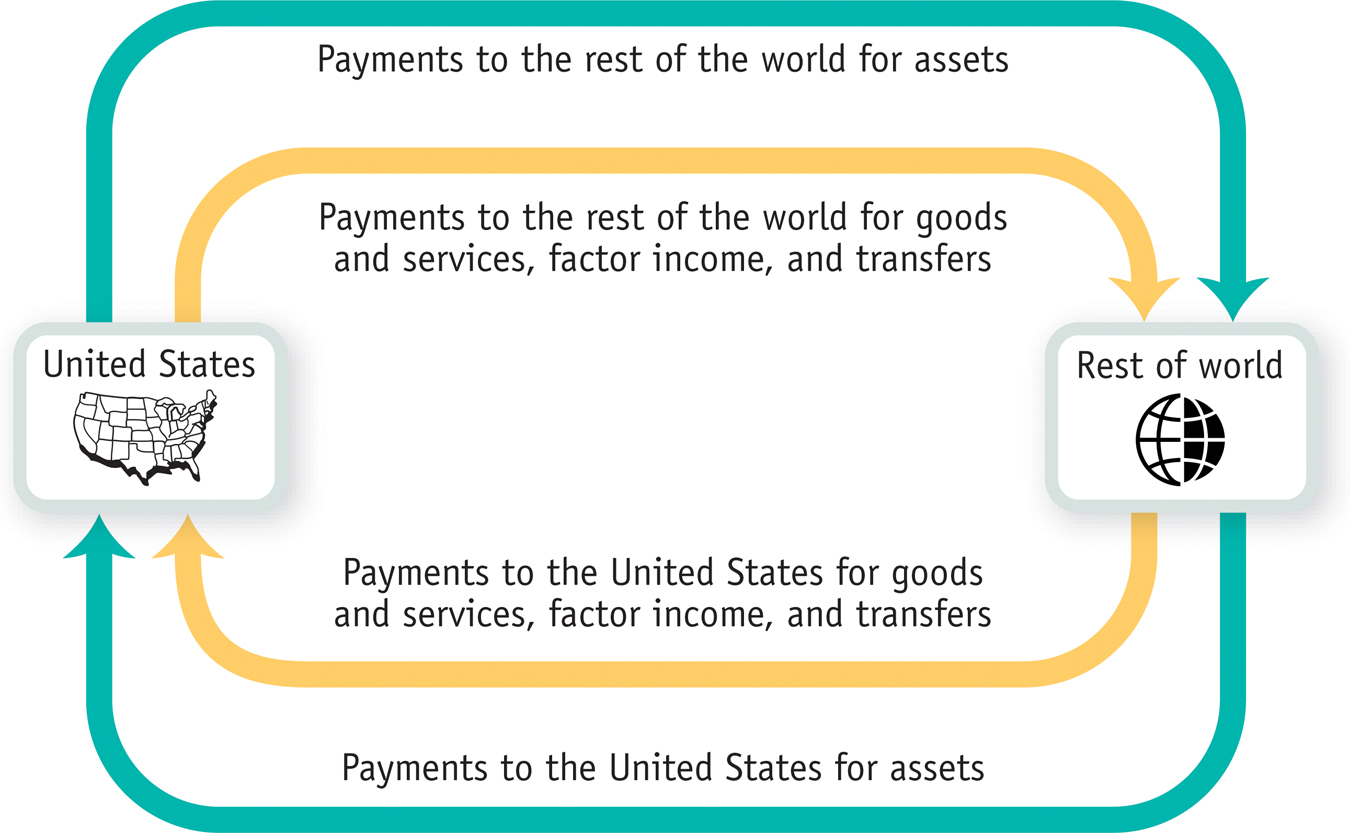

Why must Equation 79-

Money flows into the United States from the rest of the world as payment for U.S. exports of goods and services, as payment for the use of U.S.-owned factors of production, and as transfer payments. These flows (indicated by the lower yellow arrow) are the positive components of the U.S. current account. Money also flows into the United States from foreigners who purchase U.S. assets (as shown by the lower green arrow)—the positive component of the U.S. financial account.

At the same time, money flows from the United States to the rest of the world as payment for U.S. imports of goods and services, as payment for the use of foreign-

- (43-

2) Positive entries on the current account (lower yellow arrow) + Positive entries on the financial account (lower green arrow) = Negative entries on the current account (upper yellow arrow) + Negative entries on the financial account (upper green arrow)

Equation 43-

- (43-

3) Positive entries on the current account − Negative entries on the current account + Positive entries on the financial account − Negative entries on the financial account = 0

Equation 43-

But what determines the current account and the financial account?

GDP, GNP, AND THE CURRENT ACCOUNT

When we discussed national income accounting, we derived the basic equation relating GDP to the components of spending:

Y = C + I + G + X − IM

where X and IM are exports and imports, respectively, of goods and services. But as we’ve learned, the balance of payments on goods and services is only one component of the current account balance. Why doesn’t the national income equation use the current account as a whole?

The answer is that gross domestic product, GDP, is the value of goods and services produced domestically. So it doesn’t include international factor income and international transfers, two sources of income that are included in the calculation of the current account balance. The profits of Ford Motors U.K. aren’t included in America’s GDP, and the funds Latin American immigrants send home to their families aren’t subtracted from GDP.

Shouldn’t we have a broader measure that does include these sources of income? Actually, gross national product—

Why do economists use GDP rather than a broader measure? Two reasons:

- The original purpose of the national accounts was to track production rather than income.

- Data on international factor income and transfer payments are generally considered somewhat unreliable.

So if you’re trying to keep track of movements in the economy, it makes sense to focus on GDP, which doesn’t rely on these unreliable data.

Modeling the Financial Account

A country’s financial account measures its net sales of assets, such as currencies, securities, and factories, to foreigners. Those assets are exchanged for a type of capital called financial capital, which is funds from savings that are available for investment spending. We can thus think of the financial account as a measure of capital inflows in the form of foreign savings that become available to finance domestic investment spending.

What determines these capital inflows?

Part of our explanation will have to wait for a little while because some international capital flows are created by governments and central banks, which sometimes act very differently from private investors. But we can gain insight into the motivations for capital flows that are the result of private decisions by using the loanable funds model we developed previously. In using this model, we make two important simplifications:

- We simplify the reality of international capital flows by assuming that all flows are in the form of loans. In reality, capital flows take many forms, including purchases of shares of stock in foreign companies and foreign real estate as well as foreign direct investment, in which companies build factories or acquire other productive assets abroad.

- We also ignore the effects of expected changes in exchange rates, the relative values of different national currencies. We’ll analyze the determination of exchange rates later.

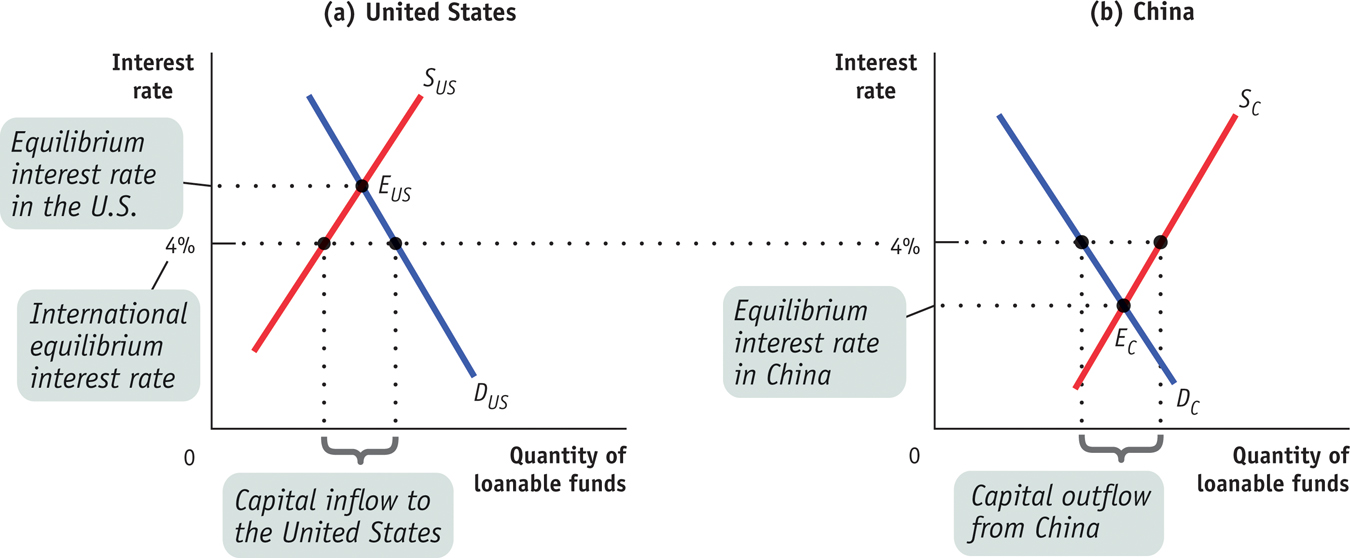

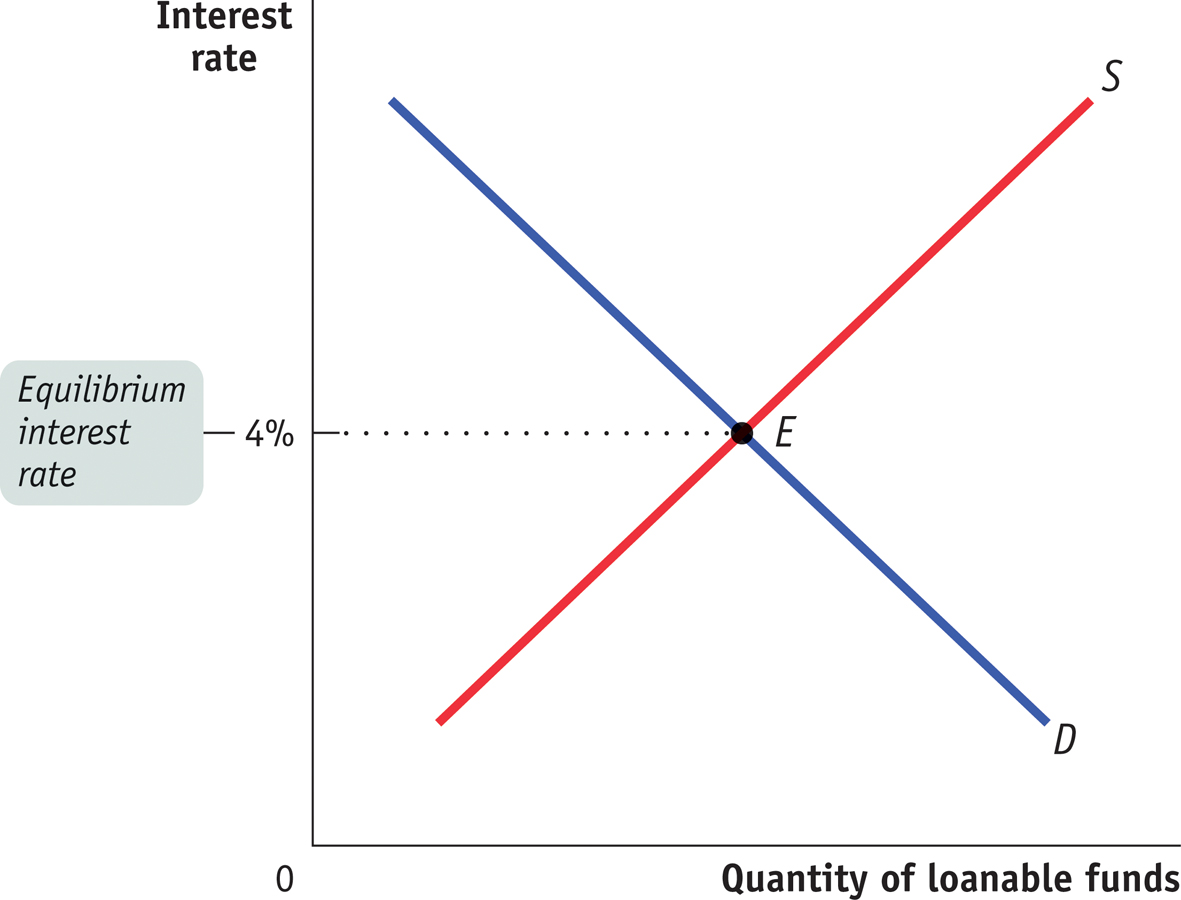

Figure 79-2 recaps the loanable funds model for a closed economy. Equilibrium corresponds to point E, at an interest rate of 4%, at which the supply of loanable funds, S, intersects the demand for loanable funds curve, D. But if international capital flows are possible, this diagram changes and E may no longer be the equilibrium. We can analyze the causes and effects of international capital flows using Figure 79-3, which places the loanable funds market diagrams for two countries side by side.

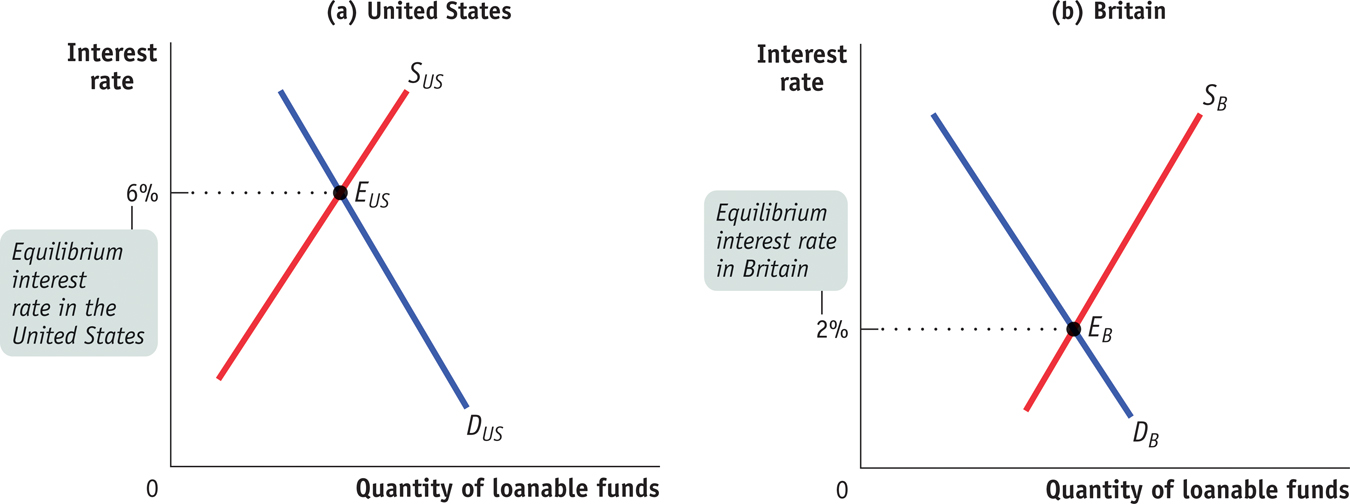

Figure 79-3 illustrates a world consisting of only two countries, the United States and Britain. Panel (a) shows the loanable funds market in the United States, where the equilibrium in the absence of international capital flows is at point EUS with an interest rate of 6%. Panel (b) shows the loanable funds market in Britain, where the equilibrium in the absence of international capital flows is at point EB with an interest rate of 2%.

Will the actual interest rate in the United States remain at 6% and that in Britain at 2%? Not if it is easy for British residents to make loans to Americans. In that case, British lenders, attracted by high American interest rates, will send some of their loanable funds to the United States. This capital inflow will increase the quantity of loanable funds supplied to American borrowers, pushing the U.S. interest rate down. At the same time, it will reduce the quantity of loanable funds supplied to British borrowers, pushing the British interest rate up. So international capital flows will narrow the gap between U.S. and British interest rates.

Let’s further suppose that British lenders regard a loan to an American as being just as good as a loan to one of their own compatriots, and American borrowers regard a debt to a British lender as no more costly than a debt to an American lender. In that case, the flow of funds from Britain to the United States will continue until the gap between their interest rates is eliminated. In other words, international capital flows will equalize the interest rates in the two countries.

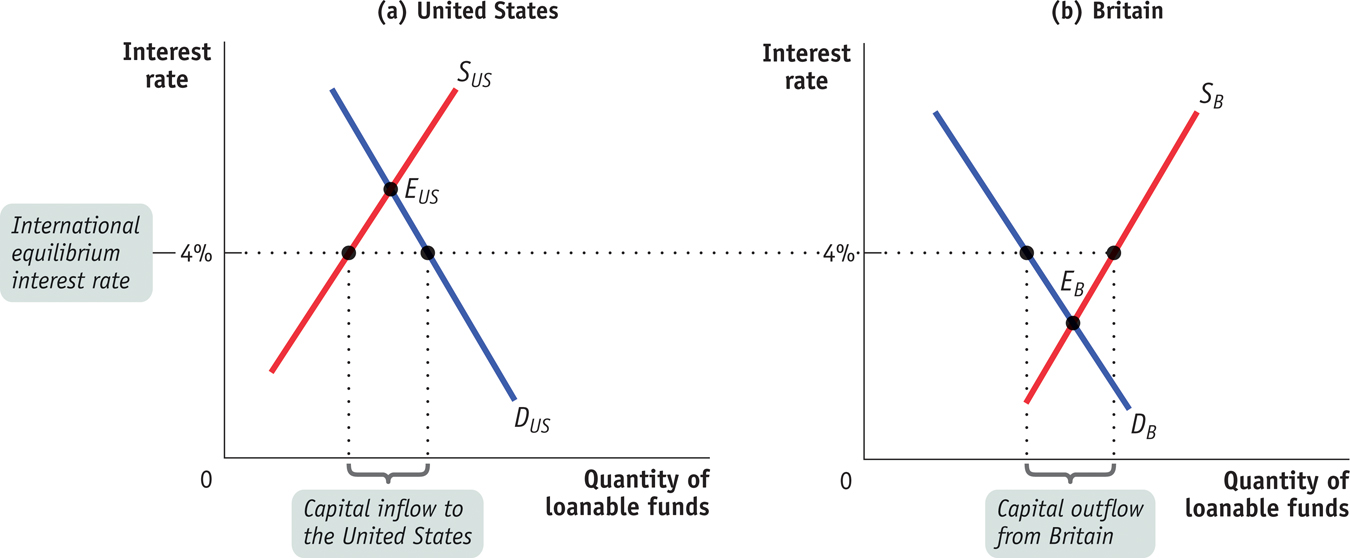

Figure 79-4 shows an international equilibrium in the loanable funds markets where the equilibrium interest rate is 4% in both the United States and Britain. At this interest rate, the quantity of loanable funds demanded by American borrowers exceeds the quantity of loanable funds supplied by American lenders. This gap is filled by “imported” funds—

At the same time, the quantity of loanable funds supplied by British lenders is greater than the quantity of loanable funds demanded by British borrowers. This excess is “exported” in the form of a capital outflow to the United States. And the two markets are in equilibrium at a common interest rate of 4%. At that interest rate, the total quantity of loans demanded by borrowers across the two markets is equal to the total quantity of loans supplied by lenders across the two markets.

In short, international flows of capital are like international flows of goods and services. Capital moves from places where it would be cheap in the absence of international capital flows to places where it would be expensive in the absence of such flows.

Underlying Determinants of International Capital Flows

The open-

International differences in the demand for funds reflect underlying differences in investment opportunities. In particular, a country with a rapidly growing economy, other things equal, tends to offer more investment opportunities than a country with a slowly growing economy. So a rapidly growing economy typically—

The classic example is the flow of capital from Britain to the United States, among other countries, between 1870 and 1914. During that era, the U.S. economy was growing rapidly as the population increased and spread westward and as the nation industrialized. This created a demand for investment spending on railroads, factories, and so on. Meanwhile, Britain had a much more slowly growing population, was already industrialized, and already had a railroad network covering the country. This left Britain with savings to spare, much of which were lent to the United States and other New World economies.

International differences in the supply of funds reflect differences in savings across countries. These may be the result of differences in private savings rates, which vary widely among countries. For example, in 2012, private savings were 22% of Japan’s GDP but only 17% of U.S. GDP. They may also reflect differences in savings by governments. In particular, government budget deficits, which reduce overall national savings, can lead to capital inflows.

Two-way Capital Flows

The loanable funds model helps us understand the direction of net capital flows—

The answer to this question is that in the real world, as opposed to the simple model we’ve just constructed, there are other motives for international capital flows besides seeking a higher rate of interest.

Individual investors often seek to diversify against risk by buying stocks in a number of countries. Stocks in Europe may do well when stocks in the United States do badly, or vice versa, so investors in Europe try to reduce their risk by buying some U.S. stocks, even as investors in the United States try to reduce their risk by buying some European stocks. The result is capital flows in both directions.

Meanwhile, corporations often engage in international investment as part of their business strategy—

Finally, some countries, including the United States, are international banking centers: people from all over the world put money in U.S. financial institutions, which then invest many of those funds overseas.

The result of these two-

79

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

Which of the balance of payments accounts do the following events affect?

-

a. Boeing, a U.S.-based company, sells a newly built airplane to China.

The sale of the new airplane to China represents an export of a good to China and so enters the current account. -

b. Chinese investors buy stock in Boeing from Americans.

The sale of Boeing stock to Chinese investors is a sale of a U.S. asset and so enters the financial account. -

c. A Chinese company buys a used airplane from American Airlines and ships it to China.

Even though the plane already exists, when it is shipped to China it is an export of a good from the United States. So the sale of the plane enters the current account. -

d. A Chinese investor who owns property in the United States buys a corporate jet, which he will keep in the United States so he can travel around America.

Because the plane stays in the United States, the Chinese investor is buying a U.S. asset. So this is identical to the answer in part b: the sale of the jet enters the financial account.

-

What effect do you think the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble and the ensuing recession had on international capital flows into the United States?

The collapse of the U.S. housing bubble and the ensuing recession led to a dramatic fall in interest rates in the United States because of the deeply depressed economy. Consequently, capital inflows into the United States dried up.

Multiple-

Question

The current account includes which of the following?

I. payments for goods and services

II. transfer payments

III. factor incomeA. B. C. D. E. Question

The balance of payments on the current account plus the balance of payments on the financial account is equal to

A. B. C. D. E. Question

The financial account was previously known as the

A. B. C. D. E. Question

The trade balance includes which of the following?

I. imports and exports of goods

II. imports and exports of services

III. net capital flowsA. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following will increase the demand for loanable funds in a country?

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

Draw two side-