1.2 84The Modern Macroeconomic Consensus

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The elements of the modern macroeconomic consensus

The elements of the modern macroeconomic consensus

The main remaining disputes

The main remaining disputes

Consensus and Conflict in Modern Macroeconomics

The 1970s and the first half of the 1980s were a stormy period for the U.S. economy (and for other major economies, too). There was a severe recession in 1974–

The Great Moderation is the period from 1985 to 2007 when the U.S. economy experienced relatively small fluctuations and low inflation.

After about 1985, however, the economy settled down. The recession of 1990–

The Great Moderation consensus combines a belief in monetary policy as the main tool of stabilization, with skepticism toward the use of fiscal policy, and an acknowledgement of the policy constraints imposed by the natural rate of unemployment and the political business cycle.

The Great Moderation was, unfortunately, followed by the Great Recession, the severe and persistent slump that followed the 2008 financial crisis. We’ll talk shortly about the policy disputes caused by the Great Recession. First, however, let’s examine the apparent consensus that emerged during the Great Moderation, which we call the Great Moderation consensus. It combines a belief in monetary policy as the main tool of stabilization, with skepticism toward the use of fiscal policy, and an acknowledgement of the policy constraints imposed by the natural rate of unemployment and the political business cycle.

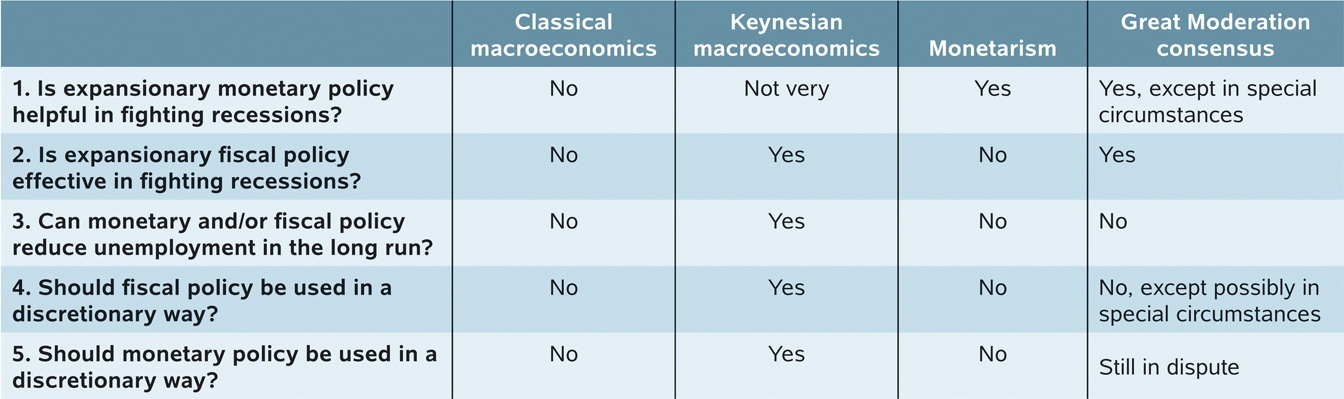

To understand where the consensus came from and what still remains in dispute, we’ll look at how macroeconomists have changed their answers to five key questions about macroeconomic policy. The five questions and the various answers given by schools of macroeconomics over the decades are summarized in Table 84-1. (In the table, new classical economics is subsumed under classical economics, and new Keynesian economics is subsumed under the Great Moderation consensus.) Notice that classical macroeconomics said no to each question; basically, classical macroeconomists didn’t think macroeconomic policy could accomplish very much. But let’s go through the questions one by one.

84-1

Five Key Questions About Macroeconomic Policy

Question 1: Is Expansionary Monetary Policy Helpful in Fighting Recessions?As we’ve seen, classical macroeconomists generally believed that expansionary monetary policy was ineffective or even harmful in fighting recessions. In the early years of Keynesian economics, macroeconomists weren’t against monetary expansion during recessions, but they tended to believe that it was of doubtful effectiveness. Milton Friedman and his followers convinced economists that monetary policy is effective after all.

Nearly all macroeconomists now agree that monetary policy can be used to shift the aggregate demand curve and to reduce economic instability. The classical view that changes in the money supply affect only aggregate prices, not aggregate output, has few supporters today. The view held by early Keynesian economists—

Question 2: Is Expansionary Fiscal Policy Effective in Fighting Recessions?Classical macroeconomists were, if anything, even more opposed to fiscal expansion than monetary expansion. Keynesian economists, on the other hand, gave fiscal policy a central role in fighting recessions. Monetarists argued that fiscal policy was ineffective if the money supply was held constant. But that strong view has become relatively rare.

Most macroeconomists now agree that fiscal policy, like monetary policy, can shift the aggregate demand curve. Most macroeconomists also agree that the government should not seek to balance the budget regardless of the state of the economy: they agree that the role of the budget as an automatic stabilizer helps keep the economy on an even keel.

Question 3: Can Monetary And/Or Fiscal Policy Reduce Unemployment in The Long Run?Classical macroeconomists didn’t believe the government could do anything about unemployment. Some Keynesian economists moved to the opposite extreme, arguing that expansionary policies could be used to achieve a permanently low unemployment rate, perhaps at the cost of some inflation. Monetarists believed that unemployment could not be kept below the natural rate.

Almost all macroeconomists now accept the natural rate hypothesis. This hypothesis leads them to accept sharp limits to what monetary and fiscal policy can accomplish. Effective monetary and fiscal policy, most macroeconomists believe, can limit the size of fluctuations of the actual unemployment rate around the natural rate, but they can’t be used to keep unemployment below the natural rate.

Question 4: Should Fiscal Policy Be Used in A Discretionary Way?As we’ve already seen, views about the effectiveness of fiscal policy have gone back and forth, from rejection by classical macroeconomists, to a positive view by Keynesian economists, to a negative view once again by monetarists. Today most macroeconomists believe that tax cuts and spending increases are at least somewhat effective in increasing aggregate demand.

Many, but not all, macroeconomists, however, believe that discretionary fiscal policy is usually counterproductive. They believe that the lags in adjusting fiscal policy mean that, all too often, policies intended to fight a slump end up intensifying a boom.

As a result, the macroeconomic consensus gives monetary policy the lead role in economic stabilization. Some, but not all, economists believe that fiscal policy must be brought back into the mix under special circumstances, in particular when interest rates are at or near the zero lower bound and the economy is in a liquidity trap. As we’ll see shortly, the proper role of fiscal policy became a huge point of contention after 2008.

Question 5: Should Monetary Policy Be Used in A Discretionary Way?Classical macroeconomists didn’t think that monetary policy should be used to fight recessions; Keynesian economists didn’t oppose discretionary monetary policy, but they were skeptical about its effectiveness. Monetarists argued that discretionary monetary policy was doing more harm than good. Where are we today? This remains an area of dispute. Today, under the Great Moderation consensus, most macreconomists agree on these three points:

- Monetary policy should play the main role in stabilization policy.

- The central bank should be independent, insulated from political pressures, in order to avoid a political business cycle.

- Discretionary fiscal policy should be used sparingly, both because of policy lags and because of the risks of a political business cycle.

However, the Great Moderation was up-

Crisis and Aftermath

The Great Recession shattered any sense among macroeconomists that they had entered a permanent era of agreement over key policy questions. Given the nature of the slump, however, this should not have come as a surprise. Why? Because the severity of the slump arguably made the policies that seemed to work during the Great Moderation inadequate.

Under the Great Moderation consensus, there had been broad agreement that the job of stabilizing the economy was best carried out by having the Federal Reserve and its counterparts abroad raise or lower interest rates as the economic situation warranted. But what should be done if the economy is deeply depressed, but the interest rates the Fed normally controls are already close to zero and can go no lower (that is, when the economy is in a liquidity trap)? Some economists called for the aggressive use of discretionary fiscal policy and/or unconventional monetary policies that might achieve results despite the zero lower bound. Others strongly opposed these measures, arguing either that they would be ineffective or that they would produce undesirable side effects.

The Debate over Fiscal Policy

In 2009 a number of governments, including that of the United States, responded with expansionary fiscal policy, or “stimulus,” generally taking the form of a mix of temporary spending measures and temporary tax cuts. From the start, however, these efforts were highly controversial.

Supporters of fiscal stimulus offered three main arguments for breaking with the normal presumption against discretionary fiscal policy:

- They argued that discretionary fiscal expansion was needed because the usual tool for stabilizing the economy, monetary policy, could no longer be used now that interest rates were near zero.

- They argued that one normal concern about expansionary fiscal policy—

that deficit spending would drive up interest rates, crowding out private investment spending— was unlikely to be a problem in a depressed economy. Again, this was because interest rates were close to zero and likely to stay there as long as the economy was depressed. - Finally, they argued that another concern about discretionary fiscal policy—

that it might take a long time to get going— was less of a concern than usual given the likelihood that the economy would be depressed for an extended period.

These arguments generally won the day in early 2009. However, opponents of fiscal stimulus raised two main objections:

- They argued that households and firms would see any rise in government spending as a sign that tax burdens were likely to rise in the future, leading to a fall in private spending that would undo any positive effect. (As you will recall, this is the Ricardian equivalence argument.)

- They also warned that spending programs might undermine investors’ faith in the government’s ability to repay its debts, leading to an increase in long-

term interest rates despite loose monetary policy.

In fact, by 2010 a number of economists were arguing that the best way to boost the economy was actually to cut government spending, which they argued would increase private-

One might have hoped that events would resolve this dispute. But the debate continues to rage today. At the time, critics of fiscal stimulus pointed out that the U.S. stimulus had failed to deliver a convincing fall in unemployment; stimulus advocates, however, had warned from the start that this was likely to happen because the stimulus was too small compared with the depth of the slump. Meanwhile, austerity programs in Britain and elsewhere had also failed to deliver an economic turnaround and, in fact, had seemed to deepen the slump; supporters of these programs, however, argued that they were nonetheless necessary to head off a potential collapse of confidence.

One thing that was clear, however, was that those who had predicted a sharp rise in U.S. interest rates due to budget deficits, leading to conventional crowding out, were wrong: by the fall of 2011, U.S. long-

The Debate over Monetary Policy

As we’ve seen, a central bank that wants to increase aggregate demand normally does this by buying short-

In 2008–

The policy of quantitative easing was controversial, facing criticisms both from those who believed the Fed was doing too much and from those who believed it wasn’t doing enough. Those who thought the Fed was doing too much were concerned about possible future inflation; they argued that the Fed would find its unconventional measures hard to reverse as the economy recovered and that the end result would be a much too expansionary monetary policy.

Critics from the other side argued that the Fed’s actions were likely to be ineffective: long-

Many of those calling for even more active policy advocated an official rise in the Fed’s inflation target. Recall the distinction between the nominal interest rate, which is the number normally cited, and the real interest rate—

Such proposals, however, led to fierce disputes. Some economists pointed out that the Fed had fought hard to drive inflation expectations down and argued that changing course would undermine hard-

These same debates continue to rage today, and it seems unlikely that a new consensus about macroeconomic policy will emerge any time soon.

AN IRISH ROLE MODEL?

Over the course of 2010 and 2011 a fierce debate raged, among both economists and policy makers, about whether countries suffering large budget deficits should move quickly to reduce those deficits if they were also suffering from high unemployment. Many economists argued that spending cuts and/or tax increases should be delayed until economies had recovered. As we explained in the text, however, others argued that fast action on deficits would actually help the economy even in the short run, by improving confidence—

How could this dispute be settled? Researchers turned their attention to historical episodes, in particular to cases in which nations had managed to combine sharp reductions in budget deficits with strong economic growth. One case in particular became a major intellectual battleground: Ireland in the second half of the 1980s.

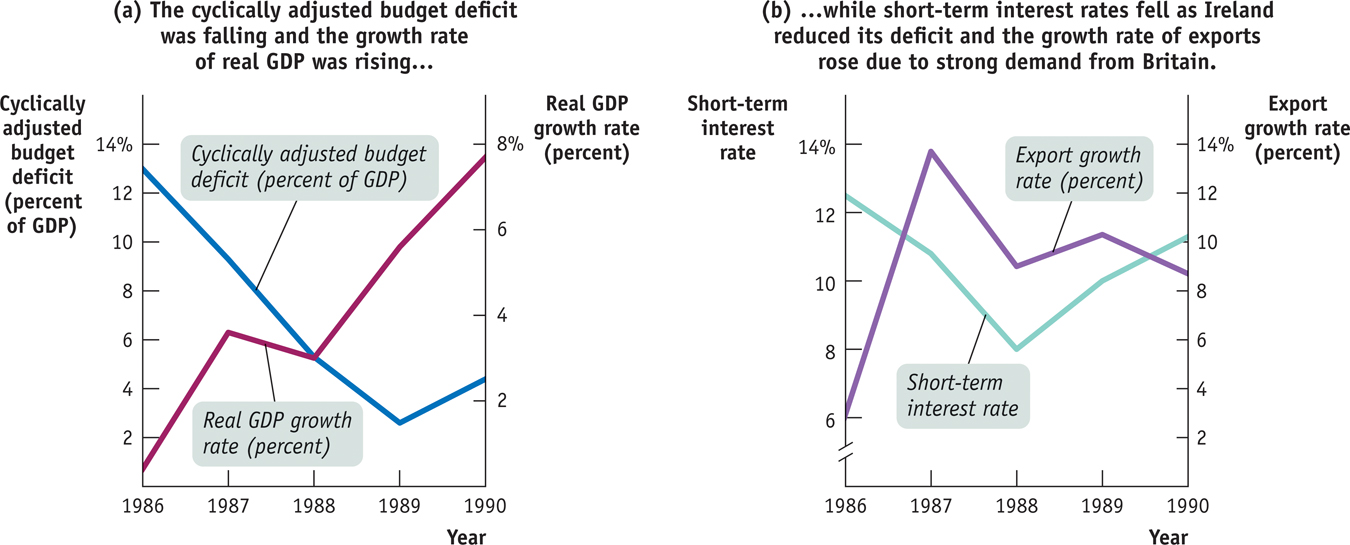

Panel (a) of Figure 84-1 shows why Ireland’s experience drew attention. It compares Ireland’s cyclically adjusted budget deficit as a percentage of GDP with its growth rate. Between 1986 and 1989 Ireland drastically reduced its underlying deficits with a combination of spending cuts and tax hikes, and the Irish economy’s growth sharply accelerated. A number of observers suggested that nations facing large deficits in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis should seek to emulate that experience.

A closer look, however, suggested that Ireland’s situation in the 1980s was very different from that facing Western economies in 2010 and 2011. Panel (b) of Figure 84-1 shows two other economic indicators for Ireland from 1986 to 1990: short-

At the same time, Ireland had a major export boom, partly due to rapid economic growth in neighboring Britain. Both factors helped offset any contractionary effects from lower spending and higher taxes.

The point was that these “cushioning” factors would not be available if, say, the United States were to slash spending. Short-

By the end of 2011 careful study of the historical record convinced most, though not all, economists studying the issue that hopes for expansionary austerity were probably misplaced. However, the debate about what the United States and other troubled economies should do raged on.

84

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

Why did the Great Recession lead to the decline of the Great Moderation consensus? Given events, why is it predictable that a new consensus has not emerged?

The liquidity trap brought on by the Great Recession greatly diminished the Great Moderation consensus because it considered monetary policy to be the main policy tool and monetary policy was now largely ineffective. The continuing disagreements over fiscal policy were now brought to the forefront as fiscal policy was used by policy makers to support their deeply depressed economies. A new consensus is unlikely to emerge anytime soon because results of the various policies have been unclear or disappointing: fiscal stimulus has failed to bring down unemployment substantially (although some say the stimulus was too small); conventional monetary policy does not work; and the Fed’s unconventional monetary policy seemed to have relatively little effect.

Multiple-

Question

Which of the following is an example of an opinion on which economists have reached a broad consensus?

I. The natural rate hypothesis holds true.

II. Discretionary fiscal policy is usually counterproductive.

III. Monetary policy is effective, especially in a liquidity trap.A. B. C. D. E. Question

Which group of macroeconomists believes that both monetary policy and fiscal policy can be effectively used to keep the unemployment rate below the natural rate?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following policy positions would a monetarist support?

A. B. C. D. Question

What is quantitative easing?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following positions are true under the Great Moderation consensus?

A. B. C. D.

Critical-

What arguments were made in favor of using expansionary fiscal policy to help the U.S. economy recover from the Great Recession?

Supporters of expansionary fiscal policy, or fiscal stimulus, offered three main arguments:• Monetary policy was not effective due to interest rates being near zero.

• Given the already near zero interest rates, expansionary fiscal policy was unlikely to result in crowding out of investment.

• Even if fiscal policy took time to implement, the economy was still likely to be in need of stimulus.

What arguments were made against the use of fiscal stimulus during the Great Recession?

Opponents of fiscal stimulus offered two main arguments:• People would see any increase in government spending as a sign that taxes were sure to rise in the future. This would reduce spending now and negate the effects of the increase in government spending.

• People might lose faith in the government’s ability to repay its debt if the level of debt continued to rise.