The Government Budget and Total Spending

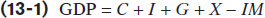

Let’s recall the basic equation of national income accounting:

The left-

The government directly controls one of the variables on the right-

To see why the budget affects consumer spending, recall that disposable income, the total income households have available to spend, is equal to the total income they receive from wages, dividends, interest, and rent, minus taxes, plus government transfers. So either an increase in taxes or a reduction in government transfers reduces disposable income. And a fall in disposable income, other things equal, leads to a fall in consumer spending. Conversely, either a decrease in taxes or an increase in government transfers increases disposable income. And a rise in disposable income, other things equal, leads to a rise in consumer spending.

The government’s ability to affect investment spending is a more complex story, which we won’t discuss in detail. The important point is that the government taxes profits, and changes in the rules that determine how much a business owes can increase or reduce the incentive to spend on investment goods.

Because the government itself is one source of spending in the economy, and because taxes and transfers can affect spending by consumers and firms, the government can use changes in taxes or government spending to shift the aggregate demand curve. And as we saw in Chapter 12, there are sometimes good reasons to shift the aggregate demand curve.

In early 2009, as this chapter’s opening story explained, the Obama administration believed it was crucial that the U.S. government act to increase aggregate demand—