Inflation and Deflation

In January 1980 the average production worker in the United States was paid $6.57 an hour. By January 2014, the average hourly earnings for such a worker had risen to $20.18 an hour. Three cheers for economic progress!

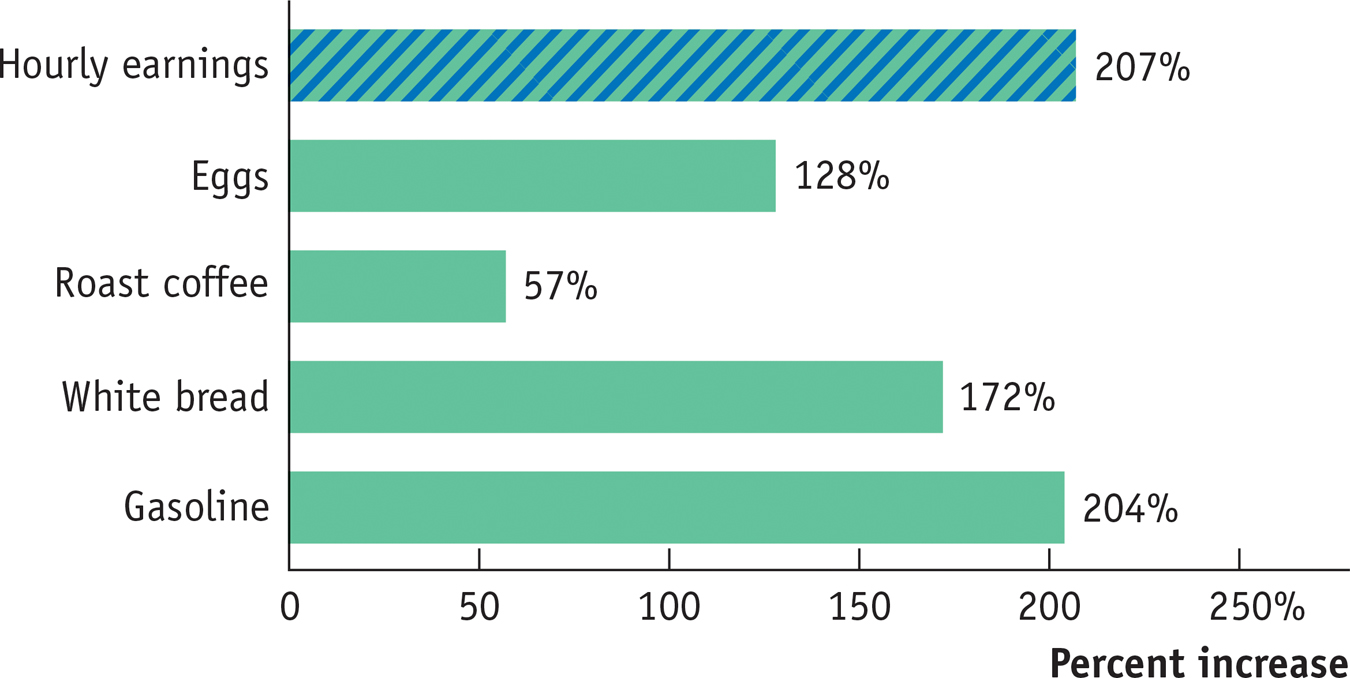

But wait. American workers were paid much more in 2014, but they also faced a much higher cost of living. In January 1980, a dozen eggs cost only about $0.88; by January 2014, that was up to $2.01. The price of a loaf of white bread went from about $0.50 to $1.37. And the price of a gallon of gasoline rose from just $1.13 to $3.38.

Figure 6-8 compares the percentage increase in hourly earnings between 1980 and 2014 with the increases in the prices of some standard items: the average worker’s paycheck went farther in terms of some goods, but less far in terms of others. Overall, the rise in the cost of living wiped out many, if not all, of the wage gains of the typical American worker from 1980 to 2014. In other words, once inflation is taken into account, the living standard of the typical American worker barely rose from 1980 to the present.

6-8

Rising Prices

A rising overall level of prices is inflation.

A falling overall level of prices is deflation.

The point is that between 1980 and 2014 the economy experienced substantial inflation: a rise in the overall level of prices. Understanding the causes of inflation and its opposite, deflation—