The Pain of Inflation and Deflation

Both inflation and deflation can pose problems for the economy. Here are two examples: inflation discourages people from holding onto cash, because cash loses value over time if the overall price level is rising. That is, the amount of goods and services you can buy with a given amount of cash falls. In extreme cases, people stop holding cash altogether and turn to barter. Deflation can cause the reverse problem. If the price level is falling, cash gains value over time. In other words, the amount of goods and services you can buy with a given amount of cash increases. So holding on to it can become more attractive than investing in new factories and other productive assets. This can deepen a recession.

The economy has price stability when the overall level of prices changes slowly or not at all.

We’ll describe other costs of inflation and deflation in Chapters 8 and 16. For now, let’s just note that, in general, economists regard price stability—

ECONOMICS in Action: A Fast (Food) Measure of Inflation

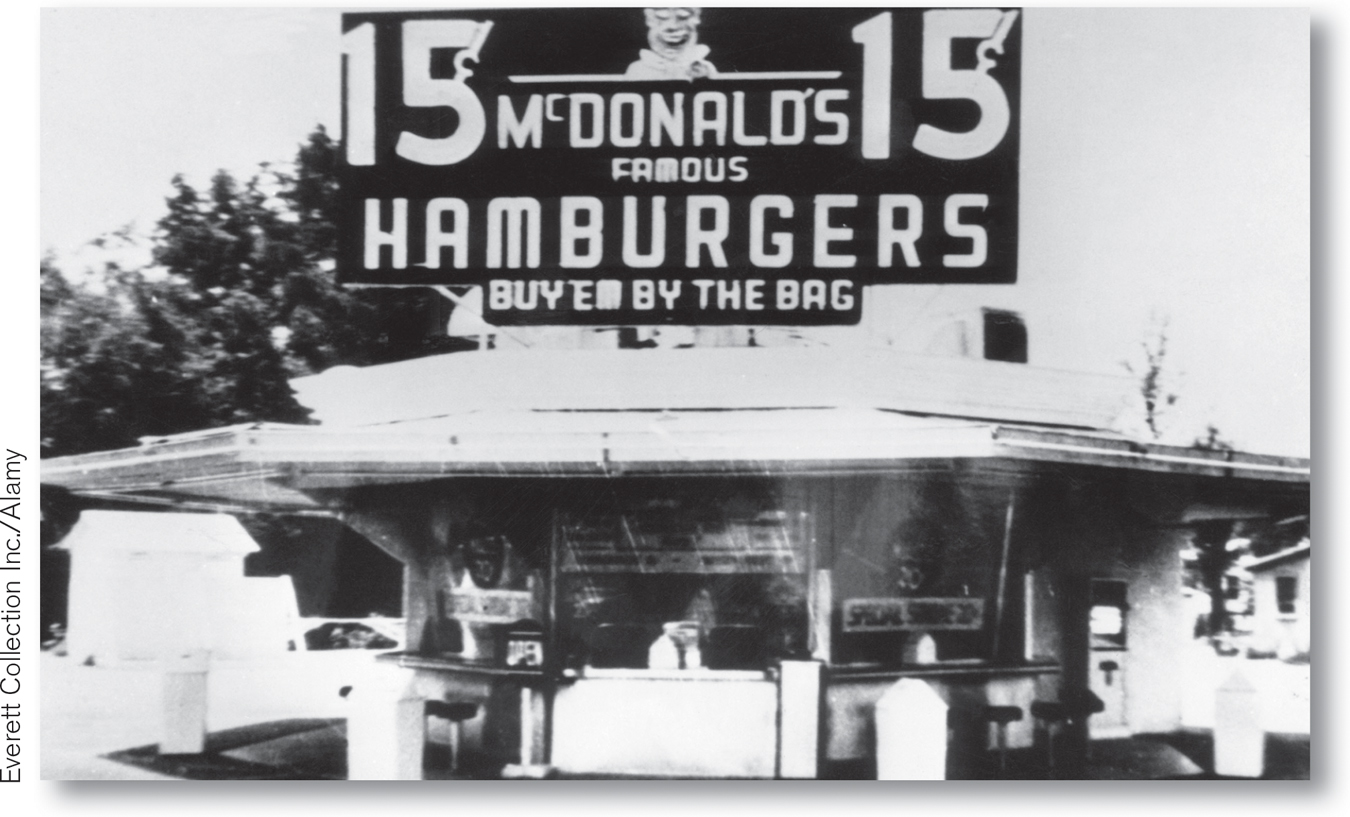

A Fast (Food) Measure of Inflation

The original McDonald’s opened in 1954. It offered fast service—

No—

Quick Review

A dollar today doesn’t buy what it did in 1980, because the prices of most goods have risen. This rise in the overall price level has wiped out most if not all of the wage increases received by the typical American worker over the past 34 years.

One area of macroeconomic study is in the overall level of prices. Because either inflation or deflation can cause problems for the economy, economists typically advocate maintaining price stability.

6-4

Question 6.7

Which of these sound like inflation, which sound like deflation, and which are ambiguous?

Gasoline prices are up 10%, food prices are down 20%, and the prices of most services are up 1–

2%. As some prices have risen but other prices have fallen, there may be overall inflation or deflation. The answer is ambiguous.

Gas prices have doubled, food prices are up 50%, and most services seem to be up 5% or 10%.

As all prices have risen significantly, this sounds like inflation.

Gas prices haven’t changed, food prices are way down, and services have gotten cheaper, too.

As most prices have fallen and others have not changed, this sounds like deflation.

Solutions appear at back of book.