Taming the Business Cycle

Modern macroeconomics largely came into being as a response to the worst recession in history—

As we explained earlier in this chapter, the work of John Maynard Keynes, published during the Great Depression, suggested that monetary and fiscal policies could be used to mitigate the effects of recessions, and to this day governments turn to Keynesian policies when recession strikes. Later work, notably that of another great macroeconomist, Milton Friedman, led to a consensus that it’s important to rein in booms as well as to fight slumps. So modern policy makers try to “smooth out” the business cycle. They haven’t been completely successful, as a look back at Figure 6-2 makes clear. It’s widely believed, however, that policy guided by macroeconomic analysis has helped make the economy more stable.

Although the business cycle is one of the main concerns of macroeconomics and historically played a crucial role in fostering the development of the field, macroeconomists are also concerned with other issues. We turn next to the question of long-

| Slumps Across the Atlantic |

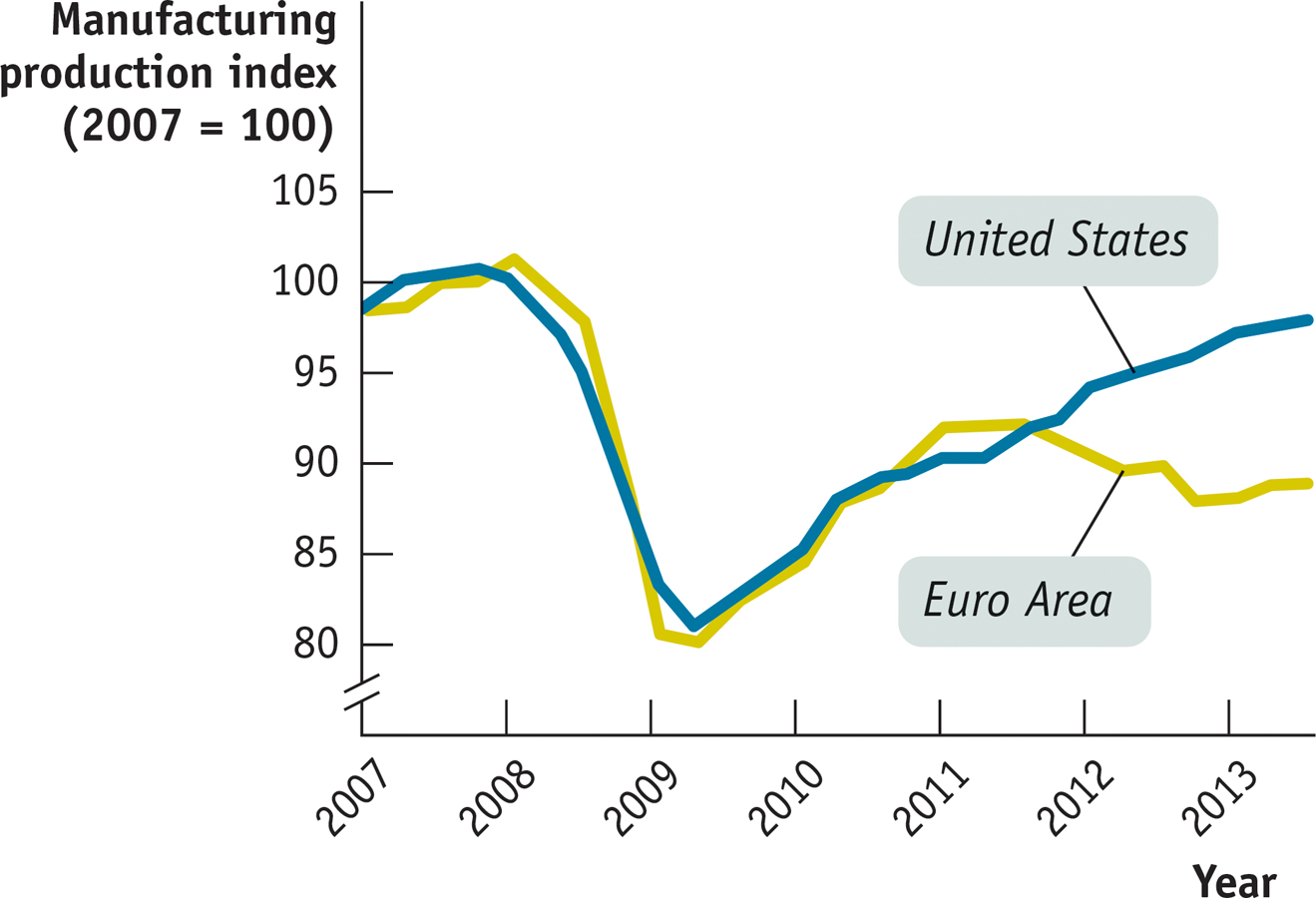

This figure shows manufacturing production from 2007 to 2013 in two of the world’s biggest economies: the United States and the Euro Area, the group of European countries that share a common currency, the euro. As you can see, both economies suffered a severe downturn in 2008–

More or less simultaneous recessions in different countries are, in fact, quite common. But that doesn’t mean that economies always or even usually move in lockstep. As you can see from the figure, both the Euro Area and the United States began to recover in mid-

What we learn from recent experience, then, is that the business cycle is to some extent an international phenomenon. But individual countries can diverge from each other for a variety of reasons, including policy differences and differences in the underlying structure of their economies.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

ECONOMICS in Action: Comparing Recessions

Comparing Recessions

The alternation of recessions and expansions seems to be an enduring feature of economic life. However, not all business cycles are created equal. In particular, some recessions have been much worse than others.

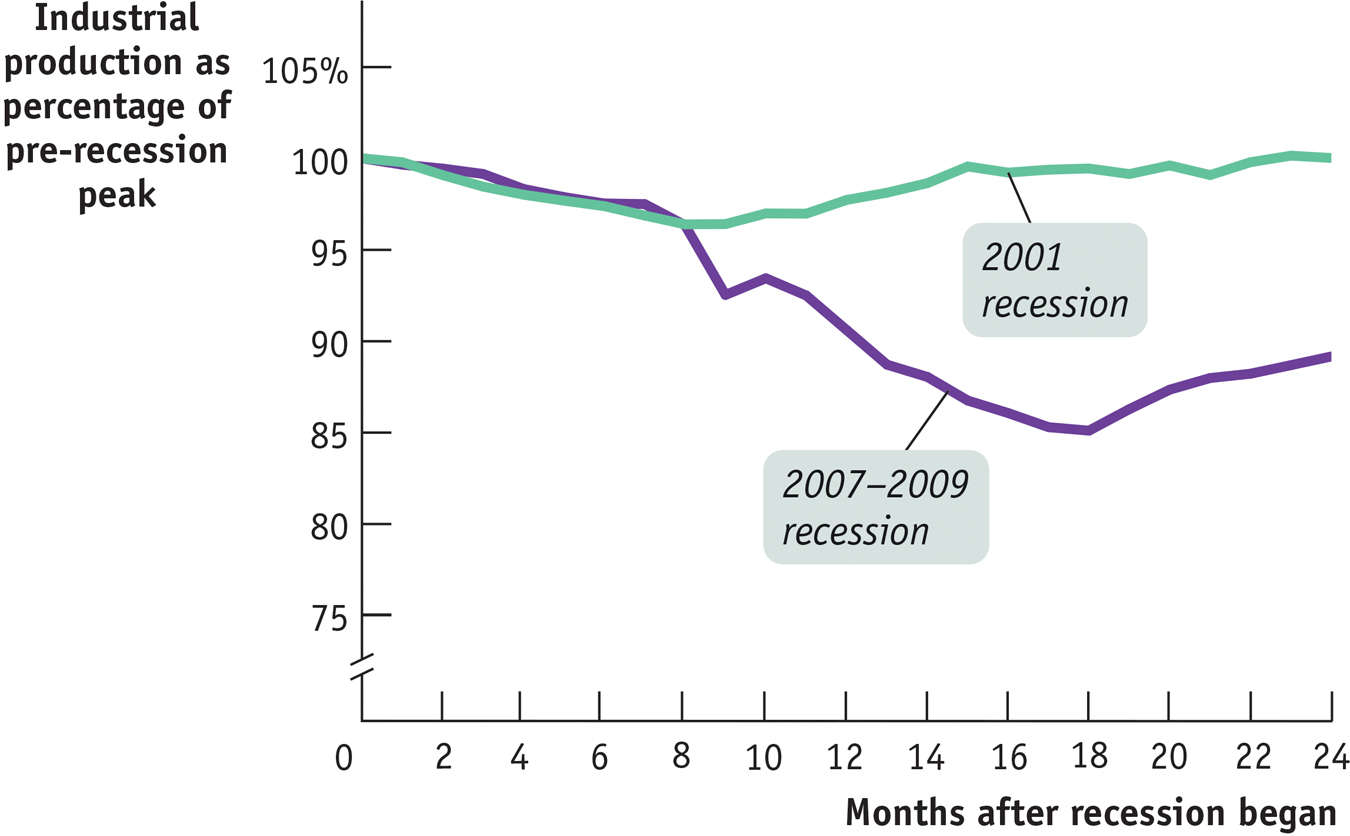

Let’s compare the two most recent U.S. recessions: the 2001 recession and the Great Recession of 2007–

6-5

Two U.S. Recessions

In Figure 6-5 we compare the depth of the recessions by looking at what happened to industrial production over the months after the recession began. In each case, production is measured as a percentage of its level at the recession’s start. Thus the line for the 2007–

Clearly, the 2007–

Of course, this was no consolation to the millions of American workers who lost their jobs, even in that mild recession.

Quick Review

The business cycle, the short-

run alternation between recessions and expansions, is a major concern of modern macroeconomics. The point at which expansion shifts to recession is a business-

cycle peak. The point at which recession shifts to expansion is a business-cycle trough.

6-2

Question 6.3

Why do we talk about business cycles for the economy as a whole, rather than just talking about the ups and downs of particular industries?

We talk about business cycles for the economy as a whole because recessions and expansions are not confined to a few industries—they reflect downturns and upturns for the economy as a whole. In downturns, almost every sector of the economy reduces output and the number of people employed. Moreover, business cycles are an international phenomenon, sometimes moving in rough synchrony across countries.

Question 6.4

Describe who gets hurt in a recession, and how.

Recessions cause a great deal of pain across the entire society. They cause large numbers of workers to lose their jobs and make it hard to find new jobs. Recessions hurt the standard of living of many families and are usually associated with a rise in the number of people living below the poverty line, an increase in the number of people who lose their houses because they can’t afford their mortgage payments, and a fall in the percentage of Americans with health insurance. Recessions also hurt the profits of firms.

Solutions appear at back of book.