1.1 36The Federal Reserve and Monetary Policy

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The functions of the Federal Reserve System

The functions of the Federal Reserve System

The major tools the Federal Reserve uses to serve its functions

The major tools the Federal Reserve uses to serve its functions

In the previous section, we learned that the Federal Reserve System serves as the central bank of the United States. It has two parts: the Board of Governors, which is part of the U.S. government, and the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, which are privately owned.

Functions of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve’s functions fall into four categories. We touched on these functions of the Federal Reserve in the previous section. We examine them again here, but then turn our full attention to the fourth function, conducting monetary policy.

- 1. PROVIDE FINANCIAL SERVICES The 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks provide financial services to depository institutions such as banks and other large institutions, including the U.S. government. The Federal Reserve is sometimes referred to as the “banker’s bank” because it holds reserves, clears checks, provides cash, and transfers funds for commercial banks—

all services that banks provide for their customers. The Federal Reserve also acts as the banker and fiscal agent for the federal government. The U.S. Treasury has its checking account with the Federal Reserve, so when the federal government writes a check, it is written on an account at the Fed. - 2. SUPERVISE AND REGULATE BANKING INSTITUTIONS The Federal Reserve is responsible for ensuring the safety and soundness of the nation’s banking and financial system. The regional Federal Reserve Banks examine and regulate commercial banks in their district. The Board of Governors also engages in regulation and supervision of financial institutions.

- 3. MAINTAIN THE STABILITY OF THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM One of the major reasons the Federal Reserve System was created was to provide the nation with a safe and stable monetary and financial system. As part of this function, Federal Reserve banks provide liquidity to financial institutions to ensure their safety and soundness.

- 4. CONDUCT MONETARY POLICY One of the Federal Reserve’s most important functions is the conduct of monetary policy, which involves the Fed using changes in the quantity of money to alter interest rates, which in turn affect the level of overall spending. The goal of monetary policy is to prevent or address extreme macroeconomic fluctuations in the U.S. economy.

How the Fed Conducts Policy

The Federal Reserve has three main policy tools at its disposal: reserve requirements, the discount rate, and, most importantly for the conduct of monetary policy, open-

The Reserve Requirement

In our discussion of bank runs, we noted that the Fed sets a minimum required reserve ratio, currently equal to 10% for checkable bank deposits. Banks that fail to maintain at least the required reserve ratio on average over a two-

The federal funds market allows banks that fall short of the reserve requirement to borrow funds from banks with excess reserves.

The federal funds rate is the interest rate determined in the federal funds market.

What does a bank do if it looks as if it has insufficient reserves to meet the Fed’s reserve requirement? Normally, it borrows additional reserves from other banks via the federal funds market, a financial market that allows banks that fall short of the reserve requirement to borrow reserves (usually just overnight) from banks that are holding excess reserves. The interest rate in this market is determined by supply and demand but the supply and demand for bank reserves are both strongly affected by Federal Reserve actions. The federal funds rate, the interest rate at which funds are borrowed and lent in the federal funds market, plays a key role in modern monetary policy.

In order to alter the money supply, the Fed can change reserve requirements. If the Fed reduces the required reserve ratio, banks will lend a larger percentage of their deposits, leading to more loans and an increase in the money supply via the money multiplier. Alternatively, if the Fed increases the required reserve ratio, banks are forced to reduce their lending, leading to a fall in the money supply via the money multiplier.

Under current practice, however, the Fed doesn’t use changes in reserve requirements to actively manage the money supply. The last significant change in reserve requirements was in 1992.

The Discount Rate

The discount rate is the interest rate the Fed charges on loans to banks.

Banks in need of reserves can also borrow from the Fed itself via the discount window. The discount rate is the interest rate the Fed charges on those loans. Normally, the discount rate is set 1 percentage point above the federal funds rate in order to discourage banks from turning to the Fed when they are in need of reserves.

In order to alter the money supply, the Fed can change the discount rate. Beginning in the fall of 2007, the Fed reduced the spread between the federal funds rate and the discount rate as part of its response to an ongoing financial crisis. As a result, by the spring of 2008 the discount rate was only 0.25 percentage points above the federal funds rate. And by January 2014 the discount rate was still only 0.68 percentage points above the federal funds rate.

If the Fed reduces the spread between the discount rate and the federal funds rate, the cost to banks of being short of reserves falls; banks respond by increasing their lending, and the money supply increases via the money multiplier. If the Fed increases the spread between the discount rate and the federal funds rate, bank lending falls—

The Fed normally doesn’t use the discount rate to actively manage the money supply. Although, as we mentioned earlier, there was a temporary surge in lending through the discount window from the middle of 2007 through 2008 in response to a financial crisis.

Today, normal monetary policy is conducted almost exclusively using the Fed’s third policy tool: open-

Open-Market Operations

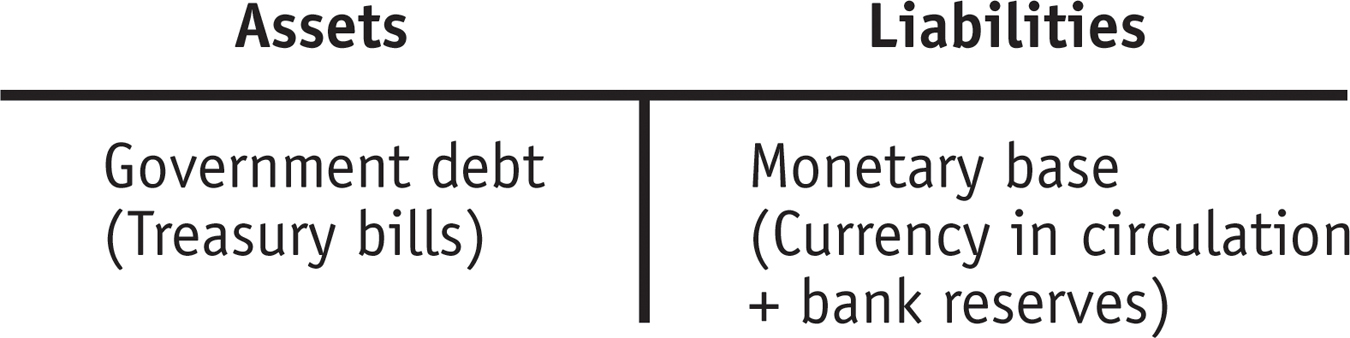

Like the banks it oversees, the Federal Reserve has assets and liabilities. The Fed’s assets consist of its holdings of debt issued by the U.S. government, mainly short-

An open-

In an open-

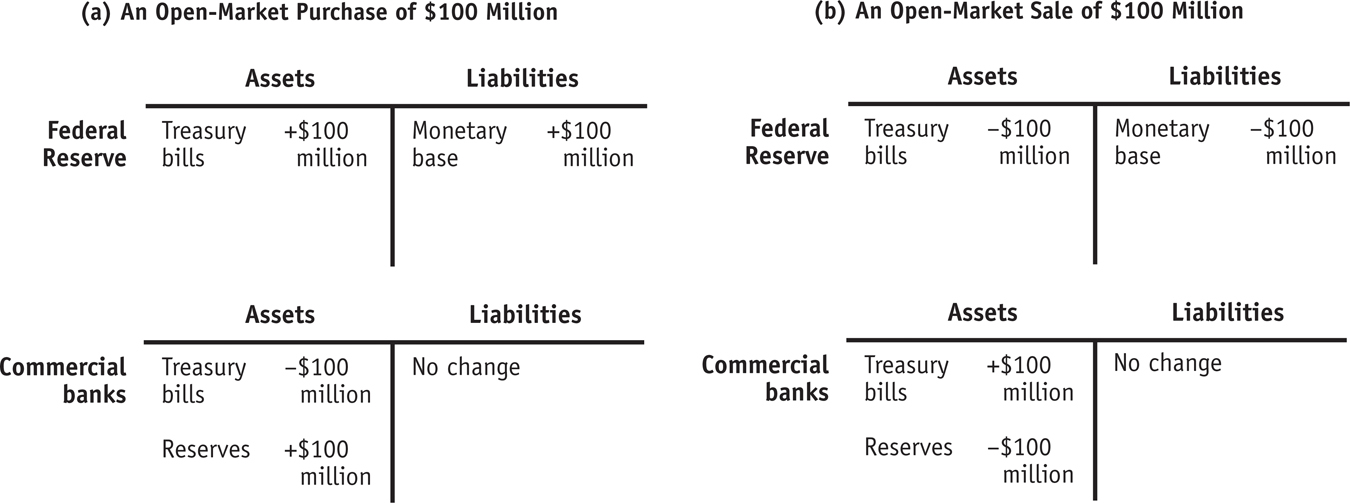

The two panels of Figure 36-2 show the changes in the financial position of both the Fed and commercial banks that result from open-

When the Fed sells U.S. Treasury bills to commercial banks, it debits the banks’ accounts, reducing their reserves. This is shown in panel (b), where the Fed sells $100 million of U.S. Treasury bills. Here, bank reserves and the monetary base decrease.

You might wonder where the Fed gets the funds to purchase U.S. Treasury bills from banks. The answer is that it simply creates them with a stroke of the pen or a click of the mouse, crediting the banks’ accounts with extra reserves. (The Fed issues currency to pay for Treasury bills only when banks want the additional reserves in the form of currency.) Remember, the modern dollar is fiat money, which isn’t backed by anything. So the Fed can increase the monetary base at its own discretion.

The change in bank reserves caused by an open-

Economists often say, loosely, that the Fed controls the money supply—

WHO GETS THE INTEREST ON THE FED’S ASSETS?

As we’ve just learned, the Fed owns a lot of assets—

You do—

Consider what happens when a fake $100 bill enters circulation. It has the same economic effect as a real $100 bill printed by the U.S. government. That is, as long as the forgery isn’t caught, the fake bill is, for all practical purposes, part of the monetary base.

Meanwhile, the Fed decides on the size of the monetary base based on economic considerations—

So a counterfeit $100 bill reduces the amount of Treasury bills the Fed can acquire and thereby reduces the interest payments going to the Fed and the U.S. Treasury. In the end, taxpayers bear the real cost of counterfeiting.

36

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

Assume that any money lent by a bank is deposited back in the banking system as a checkable deposit and that the reserve ratio is 10%. Trace out the effects of a $100 million open-

market purchase of U.S. Treasury bills by the Fed on the value of checkable bank deposits. What is the size of the money multiplier? An open-market purchase of $100 million by the Fed increases banks’ reserves by $100 million as the Fed credits their accounts with additional reserves. In other words, this open-market purchase increases the monetary base (currency in circulation plus bank reserves) by $100 million. Banks lend out the additional $100 million. Whoever borrows the money puts it back into the banking system in the form of deposits. Of these deposits, banks lend out $100 million × (1 − rr) = $100 million × 0.9 = $90 million. Whoever borrows the money deposits it back into the banking system. And banks lend out $90 million × 0.9 = $81 million, and so on. As a result, bank deposits increased by $100 million + $90 million + $81 million +… = $100 million/rr = $100 million/0.1 = $1,000 million = $1 billion. Since in this simplified example all money lent out is deposited back into the banking system, there is no increase of currency in circulation, so the increase in bank deposits is equal to the increase in the money supply. In other words, the money supply increases by $1 billion. This is greater than the increase in the monetary base by a factor of 10: in this simplified model in which deposits are the only component of the money supply and in which banks hold no excess reserves, the money multiplier is 1/rr = 10.

Multiple-

Question

Which of the following is a function of the Federal Reserve System?

I. examine commercial banks

II. print Federal Reserve notes

III. conduct monetary policyA. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following financial services does the Federal Reserve provide for commercial banks?

I. clearing checks

II. holding reserves

III. making loansA. B. C. D. E. Question

When the Fed makes a loan to a commercial bank, it charges

A. B. C. D. E. Question

If the Fed purchases U.S. Treasury bills from a commercial bank, what happens to bank reserves and the money supply?

Bank reservesMoney supplyA. B. C. D. E. Question

When banks make loans to each other, they charge the

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

Question 1.1

What are the four basic functions of the Federal Reserve System?

- provide financial services to depository institutions

- supervise and regulate banking institutions

- aintain the stability of the financial system

- conduct monetary policy