1.3 38Monetary Policy and the Interest Rate

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

How the Federal Reserve implements monetary policy, moving the interest rate to affect aggregate output

How the Federal Reserve implements monetary policy, moving the interest rate to affect aggregate output

Why monetary policy is the main tool for stabilizing the economy

Why monetary policy is the main tool for stabilizing the economy

In the previous module we developed a model of the money market to show how the interest rate is determined in the short run. Now we are ready to use this model to explain how the Federal Reserve can use monetary policy to stabilize the economy in the short run.

The Fed, the Money Supply, and the Interest Rate

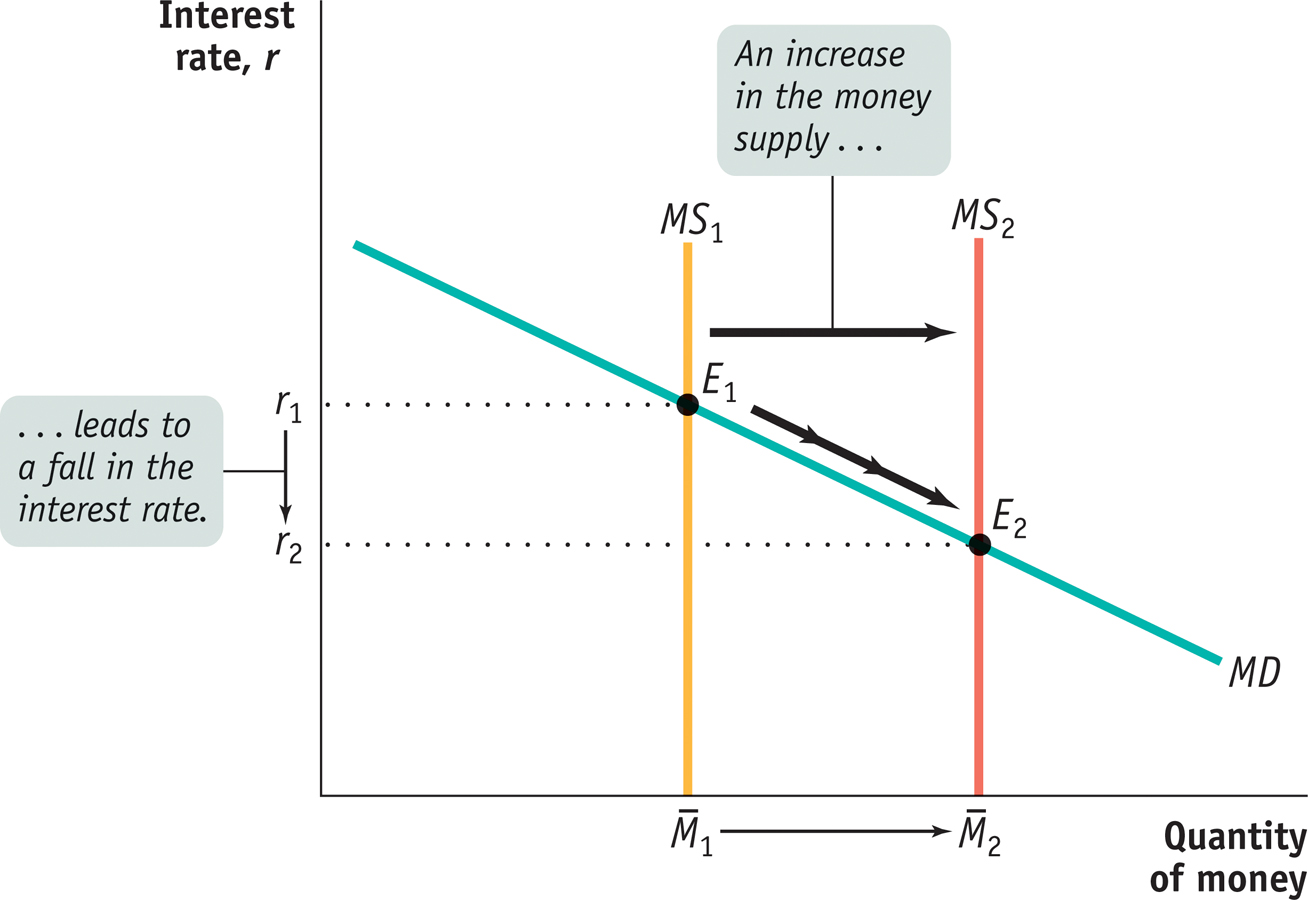

Let’s examine how the Federal Reserve can use changes in the money supply to change the interest rate. Figure 38-1 shows what happens when the Fed increases the money supply from  to

to  .

.

to

to  . In order to induce people to hold the larger quantity of money, the interest rate must fall from r1 to r2.

. In order to induce people to hold the larger quantity of money, the interest rate must fall from r1 to r2.The economy is originally in equilibrium at E1, with the equilibrium interest rate r1 and the money supply  . An increase in the money supply by the Fed to

. An increase in the money supply by the Fed to  shifts the money supply curve to the right, from MS1 to MS2, and leads to a fall in the equilibrium interest rate to r2. Why? Because r2 is the only interest rate at which the public is willing to hold the quantity of money actually supplied,

shifts the money supply curve to the right, from MS1 to MS2, and leads to a fall in the equilibrium interest rate to r2. Why? Because r2 is the only interest rate at which the public is willing to hold the quantity of money actually supplied,  .

.

So an increase in the money supply drives the interest rate down. Similarly, a reduction in the money supply drives the interest rate up. By adjusting the money supply up or down, the Fed can set the interest rate.

The target federal funds rate is the Federal Reserve’s desired federal funds rate.

In practice, at each meeting the Federal Open Market Committee decides on the interest rate to prevail for the next six weeks, until its next meeting. The Fed sets a target federal funds rate, a desired level for the federal funds rate. This target is then enforced by the Open Market Desk of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which adjusts the money supply through open-

The other tools of monetary policy, lending through the discount window and changes in reserve requirements, aren’t used on a regular basis, although the Fed used discount window lending in its efforts to address the 2008 financial crisis.

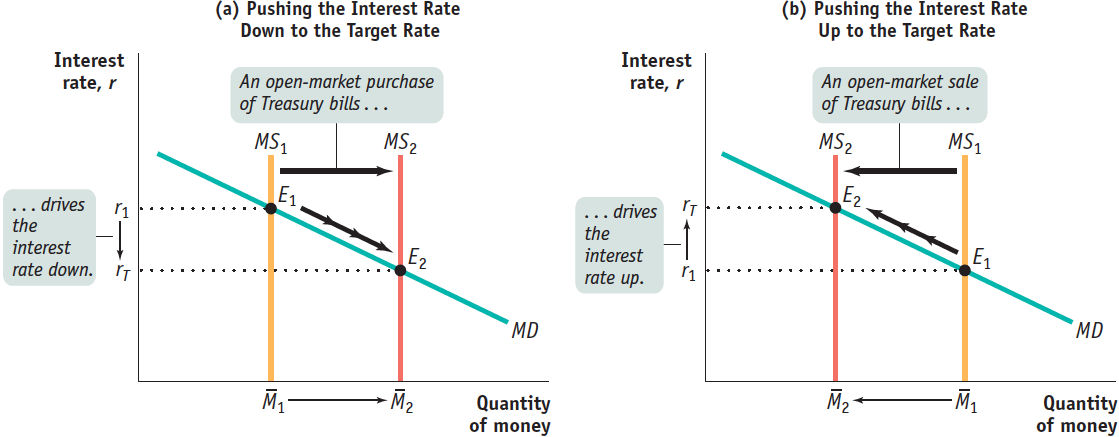

Figure 38-2 shows how the Fed adjusts the money supply in order to change the interest rate and achieve its target federal funds rate. In both panels, rT is the target federal funds rate. In panel (a), the initial money supply curve is MS1 with money supply  , and the equilibrium interest rate, r1, is above the target rate. To lower the interest rate to rT, the Fed makes an open-

, and the equilibrium interest rate, r1, is above the target rate. To lower the interest rate to rT, the Fed makes an open- . This drives the equilibrium interest rate down to the target rate, rT.

. This drives the equilibrium interest rate down to the target rate, rT.

Panel (b) shows the opposite case. Again, the initial money supply curve is MS1 with money supply  . But this time the equilibrium interest rate, r1, is below the target federal funds rate, rT. In this case, the Fed will make an open-

. But this time the equilibrium interest rate, r1, is below the target federal funds rate, rT. In this case, the Fed will make an open- via the money multiplier. The money supply curve shifts leftward from MS1 to MS2, driving the equilibrium interest rate up to the target federal funds rate, rT.

via the money multiplier. The money supply curve shifts leftward from MS1 to MS2, driving the equilibrium interest rate up to the target federal funds rate, rT.

Long-Term Interest Rates

In the previous module we mentioned that long-

Consider the case of Millie, who has already decided to place $10,000 in U.S. government bonds for the next two years. However, she hasn’t decided whether to put the money in one-

You might think that the two-

For example, if the rate of interest on one-

The same considerations apply to all investors deciding between short-

As this example suggests, long-

This is not, however, the whole story: risk is also a factor. Return to the example of Millie, deciding whether to buy one-

This means that Millie will face extra risk if she buys two-

Owing to this risk factor, long-

The fact that long-

FED REVERSES COURSE

The Fed’s decision in March 2008 to cut its target interest rate represented a dramatic reversal of Fed policy that began in September 2007.

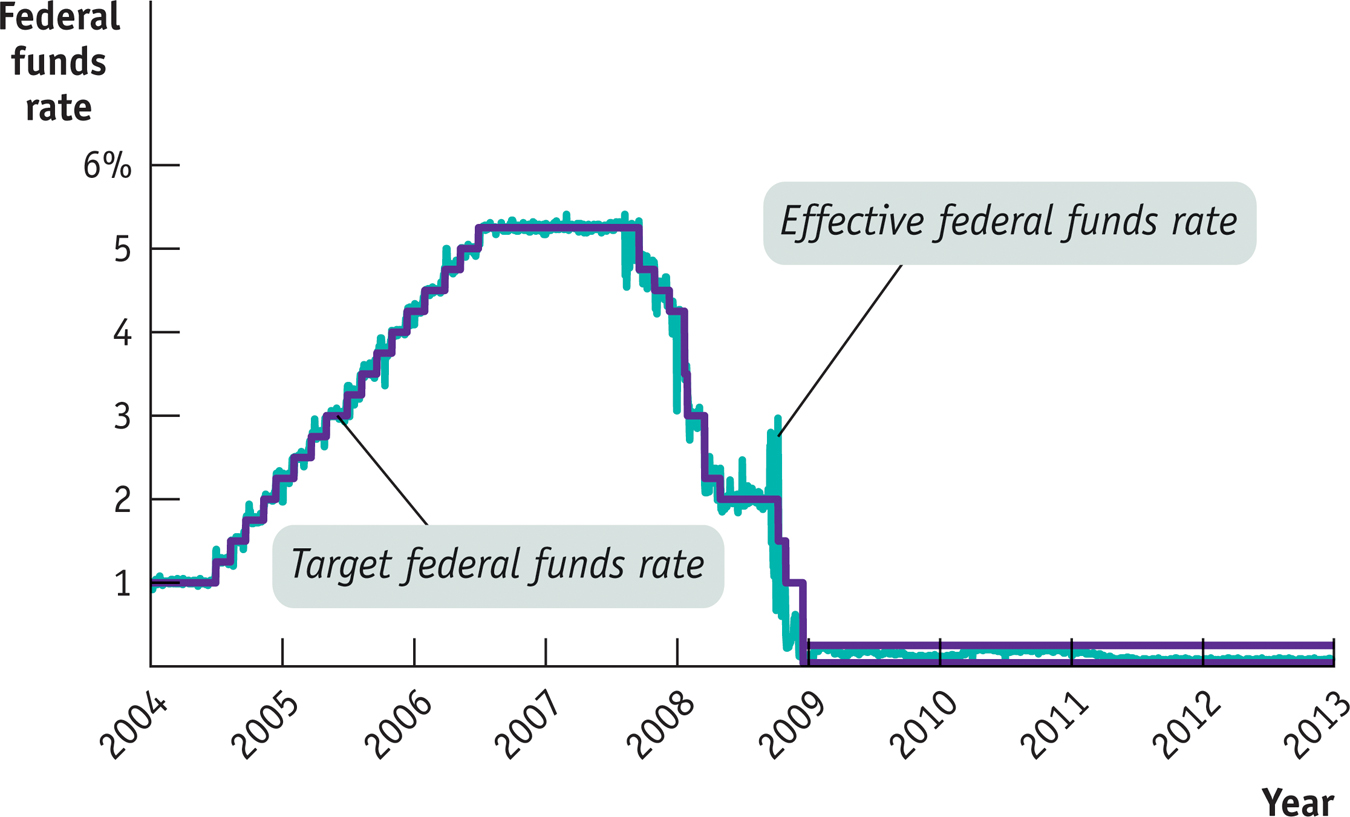

Figure 38-3 shows two interest rates from the beginning of 2004 through 2013: the target federal funds rate, decided by the Federal Open Market Committee, and the effective, or actual, rate in the market.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

As you can see, the Fed raised its target rate in a series of steps from late 2004 until the middle of 2006; it did this to head off the possibility of an overheating economy and rising inflation.

But the Fed dramatically reversed course beginning in September 2007, as falling housing prices triggered a growing financial crisis and ultimately a severe recession. And in December 2008, the Fed decided to allow the federal funds rate to move inside a target band between 0% and 0.25%. From 2009 through 2013, the Fed funds rate was kept close to zero in response to a very weak economy and high unemployment.

Figure 38-3 also shows that the Fed doesn’t always hit its target. There were a number of days, especially in 2008, when the effective federal funds rate was significantly above or below the target rate. But these episodes didn’t last long, and overall the Fed got what it wanted, at least as far as short-

Monetary Policy and Aggregate Demand

In an earlier section we saw how fiscal policy can be used to stabilize the economy. Now we will see how monetary policy—

Expansionary and Contractionary Monetary Policy

In Module 27 we learned that monetary policy shifts the aggregate demand curve. We can now explain how that works: through the effect of monetary policy on the interest rate.

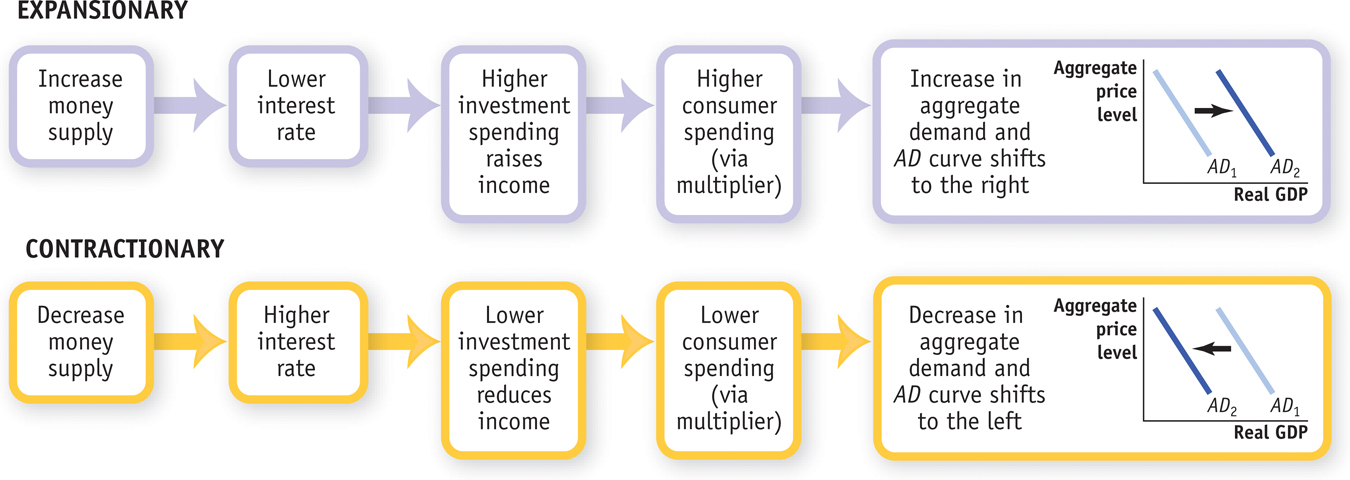

Figure 38-4 illustrates the process. Suppose, first, that the Federal Reserve wants to reduce interest rates, so it expands the money supply. As you can see in the top portion of the figure, a lower interest rate, in turn, will lead, other things equal, to more investment spending. This will in turn lead to higher consumer spending, through the multiplier process, and to an increase in aggregate output demanded.

Expansionary monetary policy is monetary policy that increases aggregate demand.

Contractionary monetary policy is monetary policy that decreases aggregate demand.

In the end, the total quantity of goods and services demanded at any given aggregate price level rises when the quantity of money increases, and the AD curve shifts to the right. Monetary policy that increases the demand for goods and services is known as expansionary monetary policy.

Suppose, alternatively, that the Federal Reserve wants to increase interest rates, so it contracts the money supply. You can see this process illustrated in the bottom portion of the diagram. Contraction of the money supply leads to a higher interest rate. The higher interest rate leads to lower investment spending, then to lower consumer spending, and then to a decrease in aggregate output demanded.

So the total quantity of goods and services demanded falls when the money supply is reduced, and the AD curve shifts to the left. Monetary policy that decreases the demand for goods and services is called contractionary monetary policy.

Monetary Policy in Practice

How does the Fed decide whether to use expansionary or contractionary monetary policy? And how does it decide how much is enough? As we know, policy makers try to fight recessions, as well as try to ensure price stability: low (though usually not zero) inflation. Actual monetary policy reflects a combination of these goals.

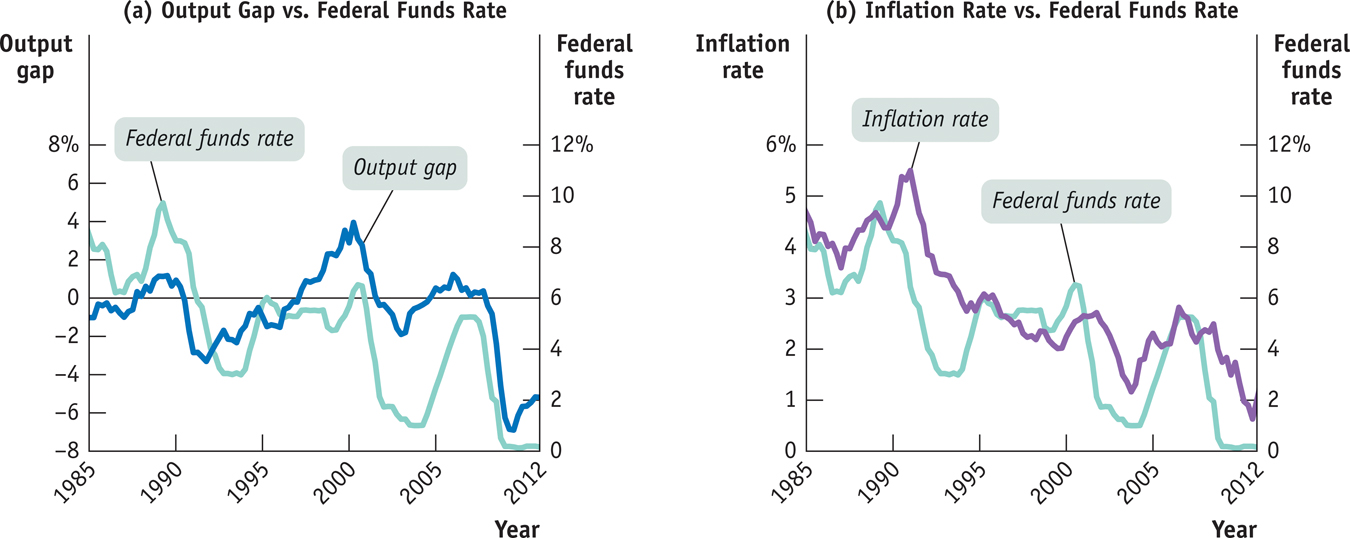

In general, the Federal Reserve and other central banks tend to engage in expansionary monetary policy when actual real GDP is below potential output. Panel (a) of Figure 38-5 shows the U.S. output gap, which we’ve previously defined as the percentage difference between actual real GDP and potential output, versus the federal funds rate since 1985. (Recall that the output gap is positive when actual real GDP exceeds potential output.) As you can see, the Fed has tended to raise interest rates when the output gap is rising—

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Congressional Budget Office; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The big exception was the late 1990s, when the Fed left rates steady for several years even as the economy developed a positive output gap (which went along with a low unemployment rate). One reason the Fed was willing to keep interest rates low in the late 1990s was that inflation was low.

Panel (b) of Figure 38-5 compares the inflation rate, measured as the rate of change in consumer prices excluding food and energy, with the federal funds rate. You can see how low inflation during the mid-

The Taylor Rule Method of Setting Monetary Policy

A Taylor rule for monetary policy is a rule that sets the federal funds rate according to the level of the inflation rate and either the output gap or the unemployment rate.

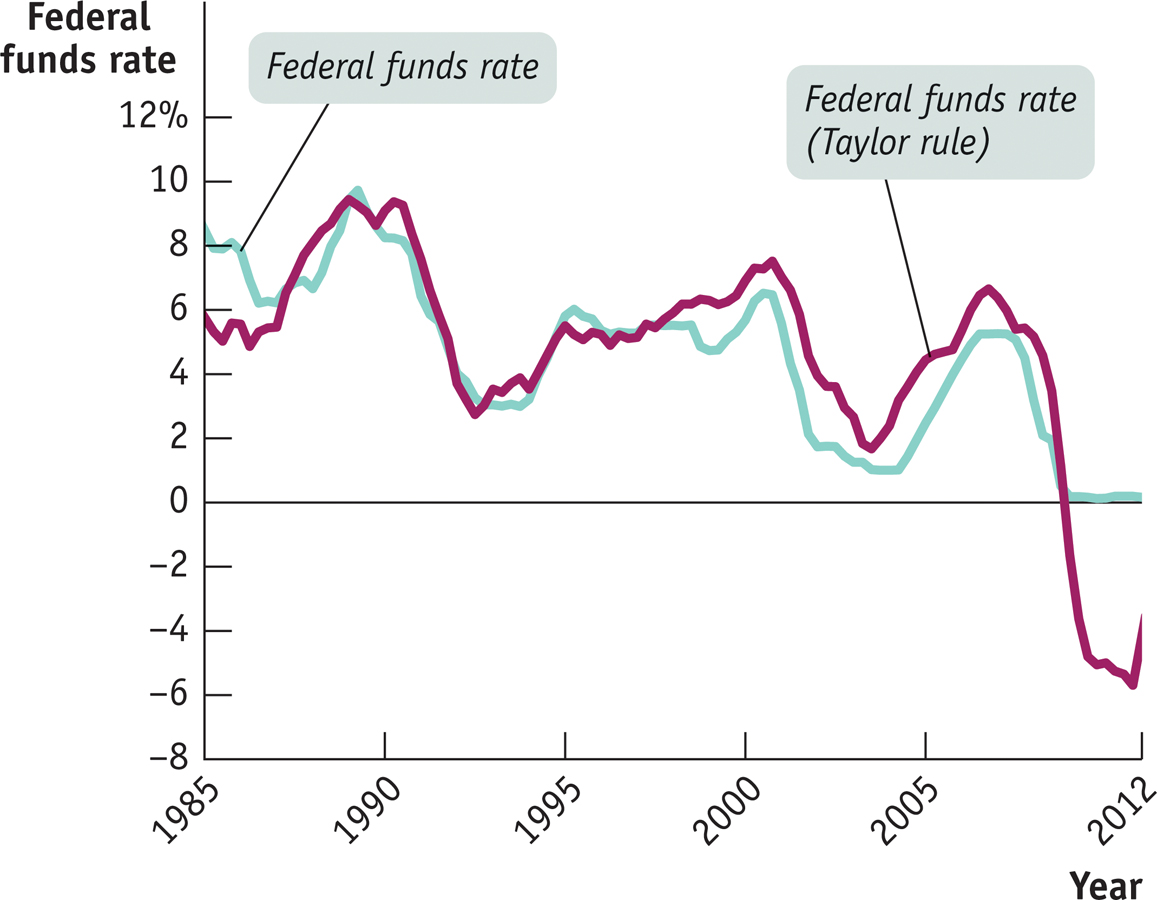

In 1993 Stanford economist John Taylor suggested that monetary policy should follow a simple rule that takes into account concerns about both the business cycle and inflation. He also suggested that actual monetary policy often looks as if the Federal Reserve was, in fact, more or less following the proposed rule. A Taylor rule for monetary policy is a rule for setting interest rates that takes into account the inflation rate and the output gap or, in some cases, the unemployment rate.

A widely cited example of a Taylor rule is a relationship among Fed policy, inflation, and unemployment estimated by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. These economists found that between 1988 and 2008 the Fed’s behavior was well summarized by the following Taylor rule:

where the inflation rate was measured by the change over the previous year in consumer prices excluding food and energy, and the unemployment gap was the difference between the actual unemployment rate and Congressional Budget Office estimates of the natural rate of unemployment.

Figure 38-6 compares the federal funds rate predicted by this rule with the actual federal funds rate from 1985 to 2012. As you can see, the Fed’s decisions were quite close to those predicted by this particular Taylor rule from 1988 through the end of 2008. We’ll talk about what happened after 2008 shortly.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Congressional Budget Office; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Glenn D. Rudebusch, “The Fed’s Monetary Policy Response to the Current Crisis,” FRBSF Economic Letter #2009-

Inflation Targeting

Until January 2012, the Fed did not explicitly commit itself to achieving a particular inflation rate. However, in January 2012, the Fed chairman at the time, Ben Bernanke, announced that the Fed would set its policy to maintain an approximately 2% inflation rate per year. With that statement, the Fed joined a number of other central banks that have explicit inflation targets.

Inflation targeting occurs when the central bank sets an explicit target for the inflation rate and sets monetary policy in order to hit that target.

So rather than using a Taylor rule to set monetary policy, they instead announced the inflation rate that they want to achieve—

Other central banks commit themselves to achieving a specific number. For example, the Bank of England has committed to keeping inflation at 2%. In practice, there doesn’t seem to be much difference between these versions: central banks with a target range for inflation seem to aim for the middle of that range, and central banks with a fixed target tend to give themselves considerable wiggle room.

One major difference between inflation targeting and the Taylor rule method is that inflation targeting is forward-

Advocates of inflation targeting argue that it has two key advantages over a Taylor rule: transparency and accountability. First, economic uncertainty is reduced because the central bank’s plan is transparent: the public knows the objective of an inflation-

Critics of inflation targeting argue that it’s too restrictive because there are times when other concerns—

Many American macroeconomists have had positive things to say about inflation targeting—

The Zero Lower Bound Problem

As Figure 38-6 shows, a Taylor rule based on inflation and the unemployment rate does a good job of predicting Federal Reserve policy from 1988 through 2008. After that, however, things go awry, and for a simple reason: with very high unemployment and low inflation, the same Taylor rule called for an interest rate less than zero, which isn’t possible.

Why aren’t negative interest rates possible? Because people always have the alternative of holding cash, which offers a zero interest rate. Nobody would ever buy a bond yielding an interest rate less than zero because holding cash would be a better alternative.

The zero lower bound for interest rates means that interest rates cannot fall below zero.

The fact that interest rates can’t go below zero—

In November 2010 the Fed began an attempt to circumvent this problem, which went by the somewhat obscure name quantitative easing. Instead of purchasing only short-

As we have already pointed out, long-

Long-

WHAT THE FED WANTS, THE FED GETS

What’s the evidence that the Fed can actually cause an economic contraction or expansion? You might think that finding such evidence is just a matter of looking at what happens to the economy when interest rates go up or down. But it turns out that there’s a big problem with that approach: the Fed usually changes interest rates in an attempt to tame the business cycle, raising rates if the economy is expanding and reducing rates if the economy is slumping. So in the actual data, it often looks as if low interest rates go along with a weak economy and high rates go along with a strong economy.

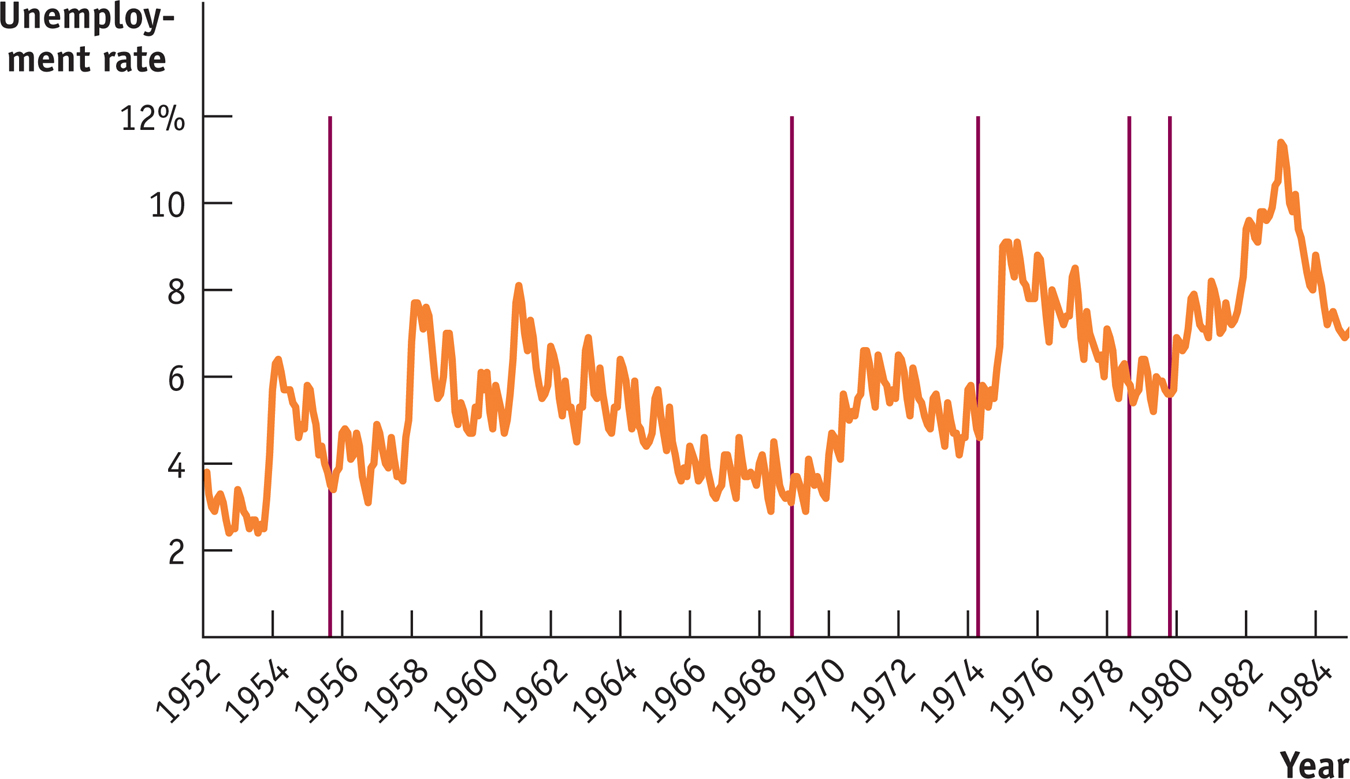

In a famous paper titled “Monetary Policy Matters,” the macroeconomists Christina Romer and David Romer solved this problem by focusing on episodes in which monetary policy wasn’t a reaction to the business cycle. Specifically, they used minutes from the Federal Open Market Committee and other sources to identify episodes “in which the Federal Reserve in effect decided to attempt to create a recession to reduce inflation.”

Rather than just using monetary policy as a tool of macroeconomic stabilization, sometimes it is used to eliminate embedded inflation—

Figure 38-7 shows the unemployment rate between 1952 and 1984 (orange) and also identifies five dates on which, according to Romer and Romer, the Fed decided that it wanted a recession (vertical red lines). In four out of the five cases, the decision to contract the economy was followed, after a modest lag, by a rise in the unemployment rate. On average, Romer and Romer found, the unemployment rate rises by 2 percentage points after the Fed decides that unemployment needs to go up.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, “Monetary Policy Matters,” Journal of Monetary Economics 34 (August 1994): 75–

So yes, the Fed gets what it wants.

38

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

Assume that there is an increase in the demand for money at every interest rate. Draw a diagram that shows what effect this will have on the equilibrium interest rate for a given money supply.

In the accompanying diagram, the increase in the demand for money is shown as a rightward shift of the money demand curve, from MD1 to MD2. This raises the equilibrium interest rate from r1 to r2.

Now assume that the Fed is following a policy of targeting the federal funds rate. What will the Fed do in the situation described in Problem 1 to keep the federal funds rate unchanged? Illustrate with a diagram.

In order to prevent the interest rate from rising, the Federal Reserve must make an open-market purchase of Treasury bills, shifting the money supply curve rightward. This is shown in the accompanying diagram as the move from MS1 to MS2.

Suppose the economy is currently suffering from a recessionary gap and the Federal Reserve uses an expansionary monetary policy to close that gap. Describe the short-

run effect of this policy on the following. -

a. the money supply curve

The money supply curve shifts to the right. -

b. the equilibrium interest rate

The equilibrium interest rate falls. -

c. investment spending

Investment spending rises, due to the fall in the interest rate. -

d. consumer spending

Consumer spending rises, due to the multiplier process. -

e. aggregate output

Aggregate output rises because of the rightward shift of the aggregate demand curve.

-

Multiple-

Question

At each meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, the Federal Reserve sets a target for which of the following?

I. the federal funds rate

II. the prime interest rate

III. the market interest rateA. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following actions can the Fed take to decrease the equilibrium interest rate?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Contractionary monetary policy attempts to _____________ aggregate demand by _____________ interest rates.

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following is a goal of monetary policy?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

When implementing monetary policy, the Federal Reserve attempts to achieve

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

What can the Fed do with each of its tools to implement expansionary monetary policy during a recession?

decrease the discount rate, decrease the reserve requirement, open-market purchasesUse a graph of the money market to explain how the Fed’s use of expansionary monetary policy affects interest rates in the short run.

Your graph should look like this.

Explain how the interest rate changes you graphed in Problem 2 affect aggregate supply and demand in the short run.

There is no change in aggregate supply; aggregate demand increases. Lower interest rates lead to greater investment spending (and more interest-sensitive consumer spending). Aggregate demand is made up of C + I + G + (X − IM), so an increase in I and C increases AD. Interest rate changes don’t affect short-run aggregate supply.Use an aggregate demand and supply graph to illustrate how expansionary monetary policy affects aggregate output in the short run.

As shown in the accompanying figure, aggregate output increases in the short run.

THE TARGET VERSUS THE MARKET

Over the years, the Federal Reserve has changed the way in which monetary policy is implemented. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, it set a target level for the money supply and altered the monetary base to achieve that target. Under this way of operating, the federal funds rate fluctuated freely. Today the Fed uses the reverse procedure, setting a target for the federal funds rate and allowing the money supply to fluctuate as it pursues that target. Do these changes in the way the Fed operates alter the way the money market works?

Over the years, the Federal Reserve has changed the way in which monetary policy is implemented. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, it set a target level for the money supply and altered the monetary base to achieve that target. Under this way of operating, the federal funds rate fluctuated freely. Today the Fed uses the reverse procedure, setting a target for the federal funds rate and allowing the money supply to fluctuate as it pursues that target. Do these changes in the way the Fed operates alter the way the money market works?

NOT AT ALL. THE MONEY MARKET WORKS THE SAME WAY AS ALWAYS: THE INTEREST RATE IS DETERMINED BY THE SUPPLY AND DEMAND FOR MONEY. THE ONLY DIFFERENCE IS THAT NOW THE FED ADJUSTS THE SUPPLY OF MONEY TO ACHIEVE ITS TARGET INTEREST RATE Although you may hear people say that the interest rate no longer reflects the supply and demand for money because the Fed sets the interest rate, this is a common misconception. It’s important not to confuse a change in the Fed’s operating procedure with a change in the way the economy works.

NOT AT ALL. THE MONEY MARKET WORKS THE SAME WAY AS ALWAYS: THE INTEREST RATE IS DETERMINED BY THE SUPPLY AND DEMAND FOR MONEY. THE ONLY DIFFERENCE IS THAT NOW THE FED ADJUSTS THE SUPPLY OF MONEY TO ACHIEVE ITS TARGET INTEREST RATE Although you may hear people say that the interest rate no longer reflects the supply and demand for money because the Fed sets the interest rate, this is a common misconception. It’s important not to confuse a change in the Fed’s operating procedure with a change in the way the economy works.

To learn more, see pages 392–