1.3 42Crises and Consequences

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

How depository banks and shadow banks differ and why both are subject to bank runs

How depository banks and shadow banks differ and why both are subject to bank runs

What happens during financial panics and banking crises and why their effects are so severe and long-

What happens during financial panics and banking crises and why their effects are so severe and long-lasting  The causes of the 2008 financial crisis

The causes of the 2008 financial crisis

How new regulation seeks to avoid another crisis

How new regulation seeks to avoid another crisis

Banking: Benefits and Dangers

As we learned earlier, banks perform an essential role in any modern economy. In this module we examine what makes banking vulnerable to a crisis—

The Purpose of Banking

We defined commercial banks and savings and loans as financial intermediaries that provide liquid financial assets in the form of deposits to savers and use their funds to finance the illiquid investment spending needs of borrowers. Deposit-

Banks will accept the savings of individuals, promising to return them on demand, but put most of those funds to work by taking advantage of the fact that not everyone wants access to those funds at the same time. A typical bank account lets you withdraw as much of your funds as you want, anytime you want—

In contrast, investment banks, hedge funds, and money market funds do not take deposits from consumers. These institutions are sometimes referred to as shadow banks. “Shadow” refers to the fact that before the 2008 crisis these financial institutions were neither closely watched nor effectively regulated. Like deposit-

Maturity transformation is the conversion of short-

More generally, depository banks borrow on a short-

A shadow bank is a nondepository financial institution that engages in maturity transformation.

A shadow bank is any financial institution that does not accept deposits but does engage in maturity transformation—

A generation ago, depository banks accounted for most banking. After about 1980, however, there was a steady rise in shadow banking. Shadow banking has grown so popular because it has not been subject to the regulations, such as capital requirements and reserve requirements, that are imposed on depository banking. So, like the unregulated trusts that set off the Panic of 1907, shadow banks can offer their customers a higher rate of return on their funds.

Shadow Banks and the Re-emergence of Bank Runs

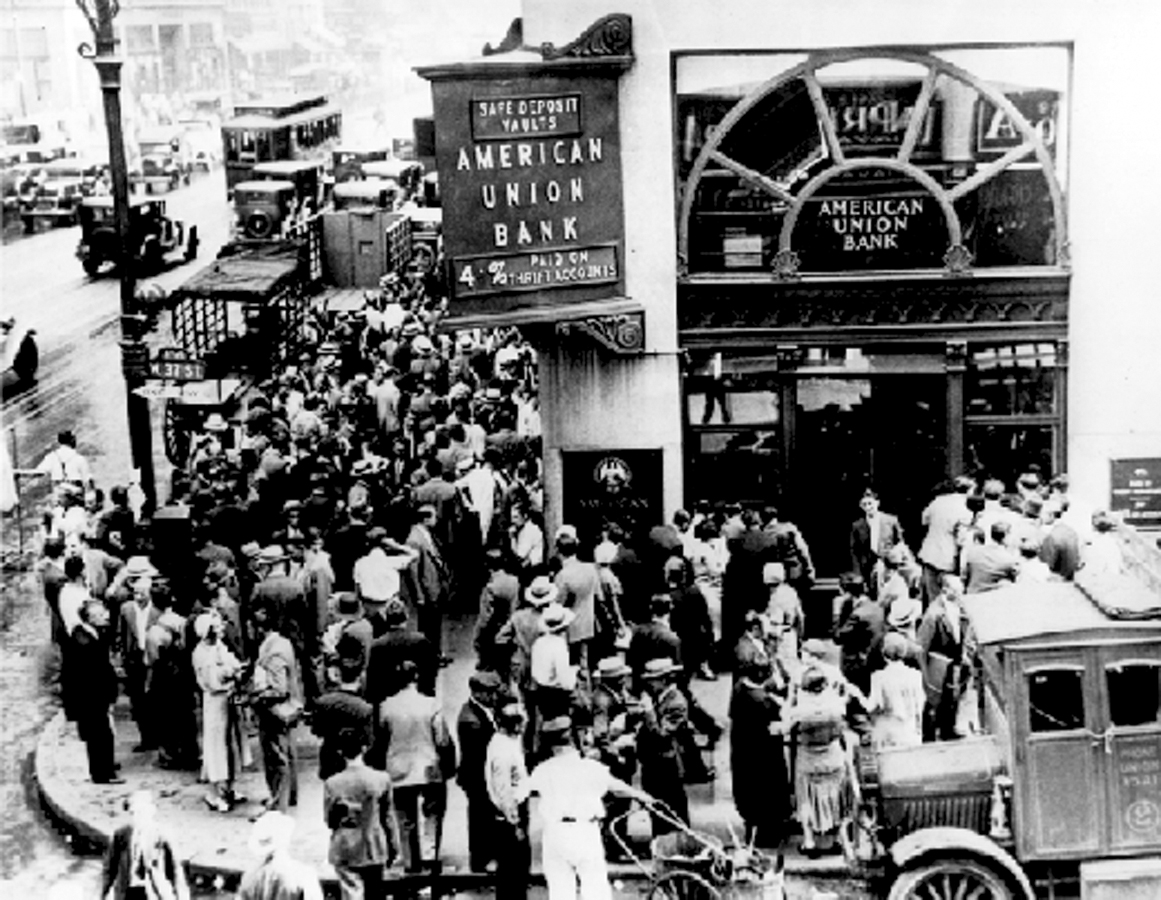

Because a depository bank keeps on hand just a small fraction of its depositors’ funds, a bank run typically results in a bank failure: the bank is unable to meet depositors’ demands for their money and closes its doors. Ominously, bank runs can be self-

To prevent such occurrences, after the 1930s the United States (and most countries) adopted wide-

Shadow banks, though, don’t take deposits. So how can they be vulnerable to a bank run? The reason is that a shadow bank, like a depository bank, engages in maturity transformation: it borrows short term and lends or invests longer term. If a shadow bank’s lenders suddenly decide one day that it’s no longer safe to lend it money, the shadow bank can no longer fund its operations. Unless it can sell its assets immediately to raise cash, it will quickly fail. This is exactly what happened in 2008 to the once venerable investment bank Lehman Brothers, which is the topic of the upcoming Economics in Action.

Banking Crises and Financial Panics

A banking crisis occurs when a large part of the depository banking sector or the shadow banking sector fails or threatens to fail.

Bank failures are common: even in a good year, several U.S. banks typically go under for one reason or another. And shadow banks sometimes fail, too. Banking crises—episodes in which a large part of the depository banking sector or the shadow banking sector fails or threatens to fail—

In an asset bubble, the price of an asset is pushed to an unreasonably high level due to expectations of further price gains.

Shared MistakesBanking crises usually owe their origins to many banks making the same mistake of investing in an asset bubble. In an asset bubble, the price of some kind of asset, such as housing, is pushed to an unreasonably high level by investors’ expectations of further price gains. For a while, such bubbles feed on themselves.

A good example of such a bubble is the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, when there was a huge boom in the construction of commercial real estate, especially office buildings. Many banks extended large loans to real estate developers, believing that the boom would continue indefinitely. By the late 1980s, it became clear that developers had gotten carried away, building far more office space than the country needed. Unable to rent out their space or forced to slash rents, a number of developers defaulted on their loans—

A similar phenomenon occurred between 2002 and 2006, when rapidly rising housing prices led many people to borrow heavily to buy a house in the belief that prices would keep rising. This process accelerated as more buyers rushed into the market and pushed housing prices up even faster.

Eventually the market runs out of new buyers and the bubble bursts. At this point asset prices fall. This, in turn, undermines confidence in financial institutions that are exposed to losses due to falling asset prices. This loss of confidence, if it’s sufficiently severe, can set in motion a financial contagion.

A financial contagion is a vicious downward spiral among depository banks or shadow banks: each bank’s failure worsens fears and increases the likelihood that another bank will fail.

Financial ContagionIn especially severe banking crises, an economy-

When a financial institution is under pressure to reduce debt and raise cash, it tries to sell assets. To sell assets quickly, though, it often has to sell them at a deep discount. The contagion comes from the fact that other financial institutions own similar assets, whose prices decline as a result of the “fire sale.” This decline in asset prices hurts the other financial institutions’ financial positions, too, leading their creditors to stop lending to them. This knock-

A financial panic is a sudden and widespread disruption of the financial markets that occurs when people suddenly lose faith in the liquidity of financial institutions and markets.

Combine an asset bubble with a huge, unregulated shadow banking system and a vicious cycle of deleveraging and it is easy to see, as the U.S. economy did in 2008, how a full-

Because banking provides much of the liquidity needed for trading financial assets like stocks and bonds, severe banking crises almost always lead to disruptions of the stock and bond markets. Disruptions of these markets, along with a headlong rush to sell assets and raise cash, lead to a vicious circle of deleveraging. As the panic unfolds, savers and investors come to believe that the safest place for their money is under their bed, and their hoarding of cash further deepens the distress.

LIGHTS OUT AT LEHMAN

By 1850, Lehman Brothers had established itself on Wall Street; by 2008, thanks to its skill at trading financial assets, Lehman Brothers was one of the nation’s top investment banks. But in September of that year, Lehman’s luck ran out.

The firm had invested heavily in subprime mortgages—

Lehman had been borrowing heavily in the short-

When Lehman fell, it set off a chain of events that came close to taking down the entire world financial system. Through securitization (a concept we defined in Module 35) financial institutions throughout the world were exposed to real estate loans that were quickly deteriorating in value as default rates on those loans rose. Credit markets froze because those with funds to lend decided it was better to sit on the funds rather than lend them out and risk losing them to a borrower who might go under like Lehman had.

Around the world, borrowers either lost their access to credit or found themselves forced to pay drastically higher interest rates. Stocks plunged, and within weeks the Dow had fallen almost 3,000 points.

Nor were the consequences limited to financial markets. The U.S. economy was already in recession when Lehman fell, but the pace of the downturn accelerated drastically in the months that followed. By the time U.S. employment bottomed out in early 2010, more than 8 million jobs had been lost. Europe and Japan were also suffering their worst recessions since the 1930s, and world trade plunged even faster than it had in the first year of the Great Depression.

Economists who knew their history quickly recognized what they were seeing: it was a modern version of a financial panic, a sudden and widespread disruption of financial markets.

Financial panics were a regular feature of the U.S. financial system before World War II. The financial panic that hit the United States in 2008 shared many features with the Panic of 1907, whose devastation prompted the creation of the Federal Reserve system. Financial panics almost always include a banking crisis, in which a significant portion of the banking sector ceases to function.

Financial panics and banking crises have happened fairly often, sometimes with disastrous effects on output and employment. Chile’s 1981 banking crisis was followed by a 19% decline in real GDP per capita and a slump that lasted through most of the following decade. Finland’s 1990 banking crisis was followed by a surge in the unemployment rate from 3.2% to 16.3%. Japan’s banking crisis of the early 1990s led to more than a decade of economic stagnation.

The Consequences of Banking Crises

If banking crises affected only banks, they wouldn’t be as serious a concern. In fact, however, banking crises are almost always associated with recessions, and severe banking crises are associated with the worst economic slumps. Furthermore, history shows that recessions caused in part by banking crises inflict sustained economic damage, with economies taking years to recover.

Banking Crises, Recessions, and Recovery

A severe banking crisis is one in which a large fraction of the banking system either fails outright (that is, goes bankrupt) or suffers a major loss of confidence and must be bailed out by the government. Such crises almost invariably lead to deep recessions, which are usually followed by slow recoveries.

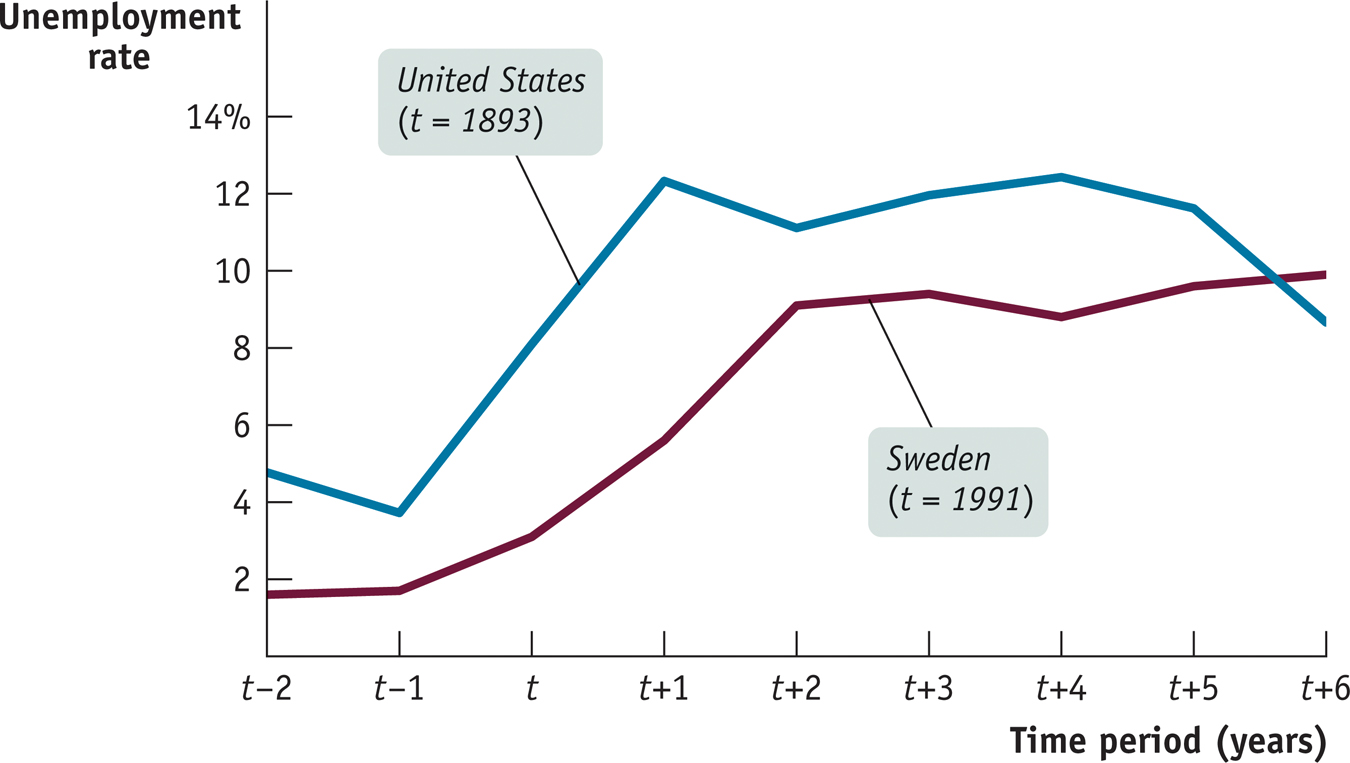

Figure 42-1 illustrates this phenomenon by tracking unemployment in the aftermath of two banking crises widely separated in space and time: the Panic of 1893 in the United States and the Swedish banking crisis of 1991. In the figure, t represents the year of the crisis: 1893 for the United States, 1991 for Sweden. As the figure shows, these crises on different continents, almost a century apart, produced similarly devastating results: unemployment shot up and came down only slowly and erratically so that, even five years after the crisis, the number of jobless remained high by pre-

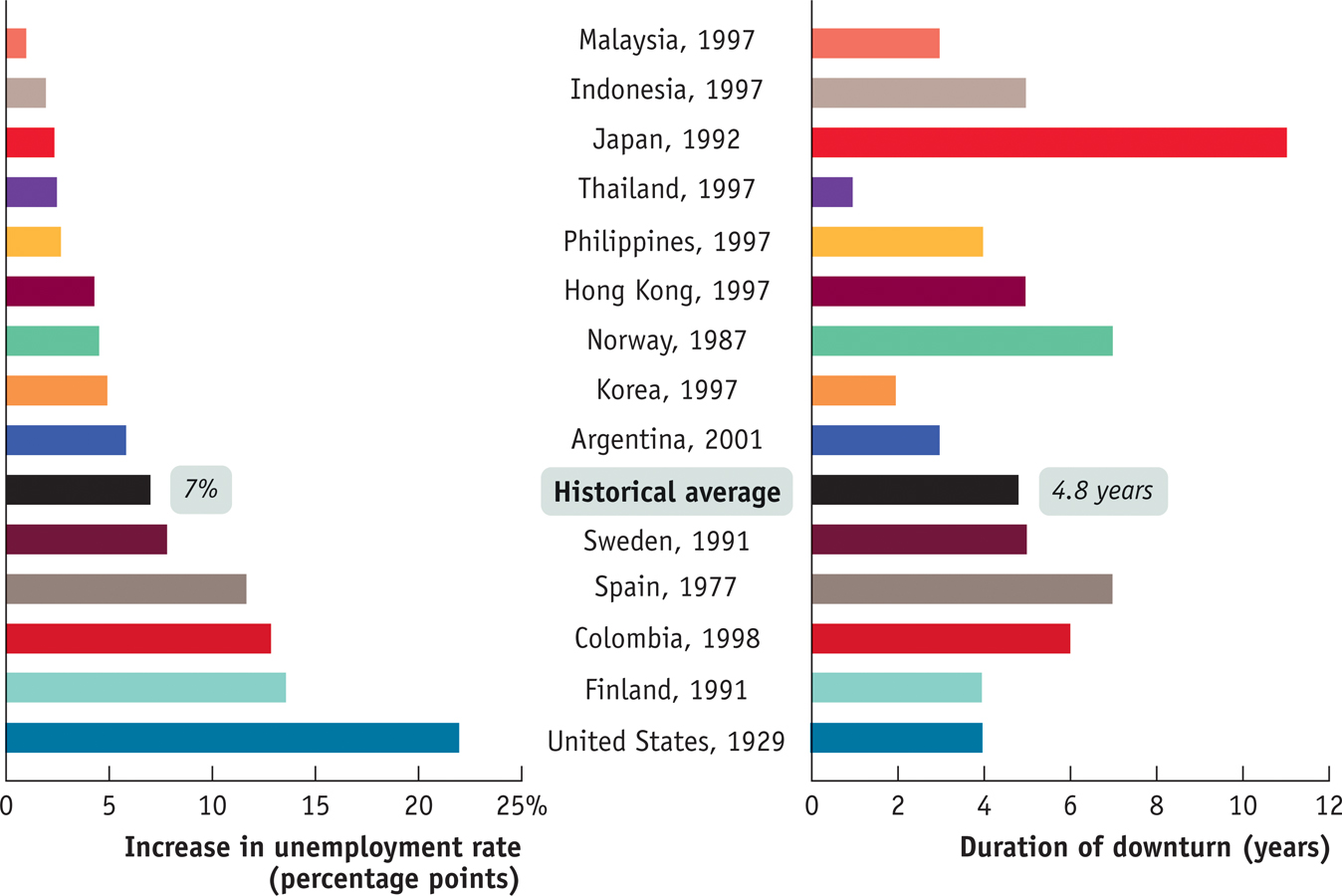

These historical examples are typical. Figure 42-2, taken from a widely cited study by the economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, compares employment performance in the wake of a number of severe banking crises. The bars on the left show the rise in the unemployment rate during and following the crisis; the bars on the right show the time it took before unemployment began to fall.

The numbers in the figure are shocking: on average, severe banking crises have been followed by a 7 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate, and in many cases it has taken four years or more before the unemployment rate even begins to fall, let alone returns to pre-

Why Are Banking-Crisis Recessions So Bad?

It’s not difficult to see why banking crises normally lead to recessions. There are three main reasons: a credit crunch arising from reduced availability of credit, financial distress caused by a debt overhang, and the loss of monetary policy effectiveness.

- Credit crunch. The disruption of the banking system typically leads to a reduction in the availability of credit called a credit crunch, in which potential borrowers either can’t get credit at all or must pay very high interest rates. Unable to borrow or unwilling to pay higher interest rates, businesses and consumers cut back on spending, pushing the economy into a recession.

- Debt overhang. A banking crisis typically pushes down the prices of many assets through a vicious cycle of deleveraging, as distressed borrowers try to sell assets to raise cash, pushing down asset prices and causing further financial distress. As we have already seen, deleveraging is a factor in the spread of the crisis, lowering the value of the assets banks hold on their balance sheets and so undermining their solvency. It also creates problems for other players in the economy.

To take an example all too familiar from recent events, falling housing prices can leave consumers substantially poorer, especially because they are still stuck with the debt they incurred to buy their homes. A banking crisis, then, tends to leave consumers and businesses with a debt overhang: high debt but diminished assets. Like a credit crunch, this also leads to a fall in spending and a recession as consumers and businesses cut back in order to reduce their debt and rebuild their assets. - Loss of monetary policy effectiveness. A key feature of banking-

crisis recessions is that when they occur, monetary policy— the main tool of policy makers for fighting negative demand shocks caused by a fall in consumer and investment spending— loses much of its effectiveness. The ineffectiveness of monetary policy makes banking- crisis recessions especially severe and long- lasting.

In a credit crunch, potential borrowers either can’t get credit at all or must pay very high interest rates.

A debt overhang occurs when a vicious cycle of deleveraging leaves a borrower with high debt but diminished assets.

Recall how the Fed normally responds to a recession: it engages in open-

Under normal conditions, this policy response is highly effective. In the aftermath of a banking crisis, though, the whole process tends to break down. Banks, fearing runs by depositors or a loss of confidence by their creditors, tend to hold on to excess reserves rather than lend them out. Meanwhile, businesses and consumers, finding themselves in financial difficulty due to the plunge in asset prices, may be unwilling to borrow even if interest rates fall. As a result, even very low interest rates may not be enough to push the economy back to full employment.

In the previous module we described the problem of the economy’s falling into a liquidity trap, when even pushing short-

The inability of the usual tools of monetary policy to offset the macroeconomic devastation caused by banking crises is the major reason such crises produce deep, prolonged slumps. The obvious solution is to look for other policy tools. In fact, governments do typically take a variety of special steps when banks are in crisis.

Governments Step In

Before the Great Depression, policy makers often allowed banks to fail in the belief that market forces should be allowed to work. Since the catastrophe of the 1930s, though, almost all policy makers have believed that it’s necessary to take steps to contain the damage from bank failures. In general, central banks and governments take three main kinds of action in an effort to limit the fallout from banking crises:

- They act as the lender of last resort.

- They offer guarantees to depositors and others with claims on banks.

- In an extreme crisis, a central bank will step in and provide financing to private credit markets.

A lender of last resort is an institution, usually a country’s central bank, that provides funds to financial institutions when they are unable to borrow from the private credit markets.

1. Lender of Last ResortAn institution, usually a country’s central bank, that provides funds to financial institutions when they are unable to borrow from the private credit markets is known as a lender of last resort. In particular, the central bank can provide cash to a bank that is facing a run by depositors but is fundamentally solvent, making it unnecessary for the bank to engage in fire sales of its assets to raise cash. This acts as a lifeline, working to prevent a loss of confidence in the bank’s solvency from turning into a self-

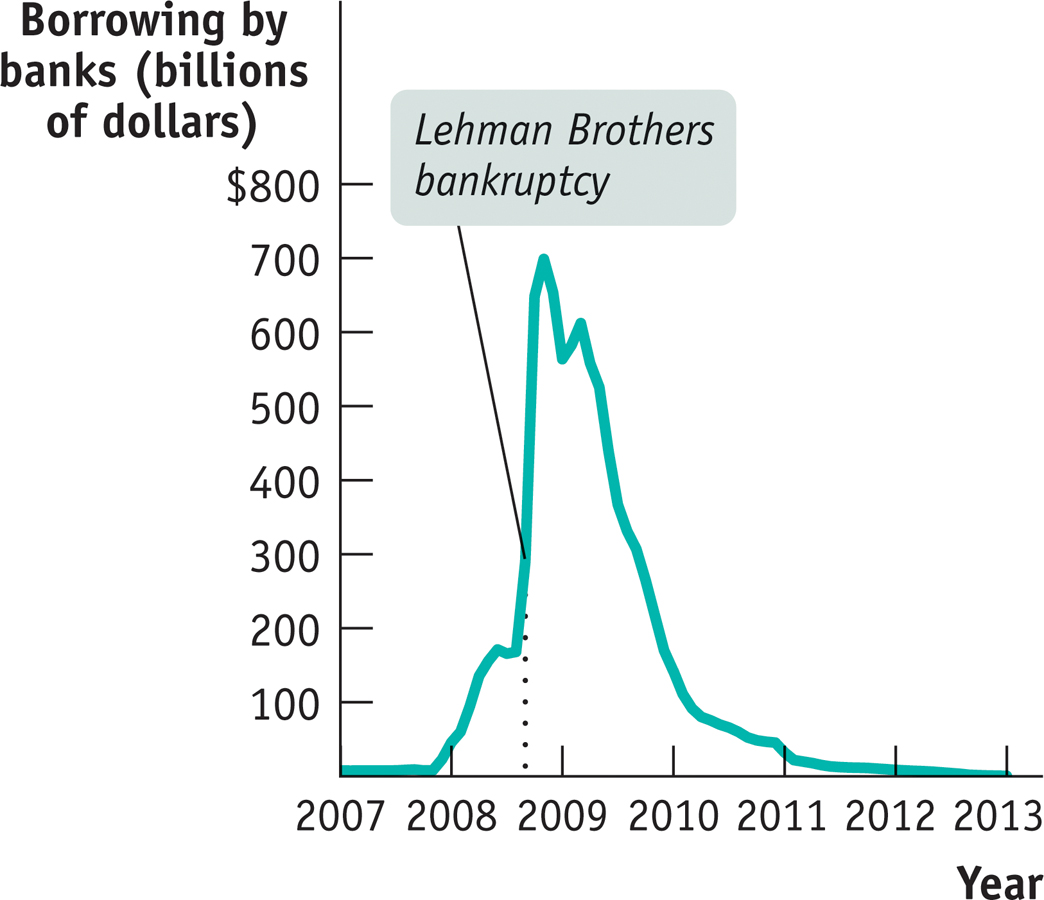

Did the Federal Reserve act as a lender of last resort in the 2008 financial crisis? Very much so. Figure 42-3 shows borrowing by banks from the Fed: commercial banks borrowed negligible amounts from the central bank before the crisis, but their borrowing rose to $700 billion in the months following Lehman’s failure. To get a sense of how large this borrowing was, note that total bank reserves before the crisis were less than $50 billion—

2. Government GuaranteesThere are limits, though, to how much a lender of last resort can accomplish: it can’t restore confidence in a bank if there is good reason to believe the bank is fundamentally insolvent. If the public believes that the bank’s assets aren’t worth enough to cover its debts even if it doesn’t have to sell these assets on short notice, a lender of last resort isn’t going to help much. And in major banking crises there are often good reasons to believe that many banks are truly bankrupt.

In such cases, governments often step in to guarantee banks’ liabilities. In 2007, a bank run hit the British bank Northern Rock, ceasing only when the British government stepped in and guaranteed all deposits at the bank, regardless of size. Ireland’s government eventually stepped in to guarantee repayment of not just deposits at all of the nation’s banks, but all bank debts. Sweden did the same thing after its 1991 banking crisis.

When governments take on banks’ risk, they often take ownership of the banks they are rescuing. Northern Rock was nationalized in 2008. Sweden nationalized a significant part of its banking system in 1992. In the United States, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation routinely seizes banks that are no longer solvent; it seized 140 banks in 2009. Ireland, however, chose not to seize any of the banks whose debts were guaranteed by taxpayers.

These government takeovers are almost always temporary. In general, modern governments want to save banks, not run them. So they “reprivatize” nationalized banks, selling them to private buyers, as soon as they believe they can.

3. Provider of Direct FinancingDuring the depths of the 2008 financial crisis the Federal Reserve expanded its operations beyond the usual measures of open-

The 2008 Crisis and Its Aftermath

As we’ve just seen, banking crises have typically been followed by major economic problems. How did the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008 compare with this historical experience? The answer, unfortunately, is that history has proved a very good guide: once again, the economic damage from the financial crisis was both large and prolonged.

Severe Crisis, Slow Recovery

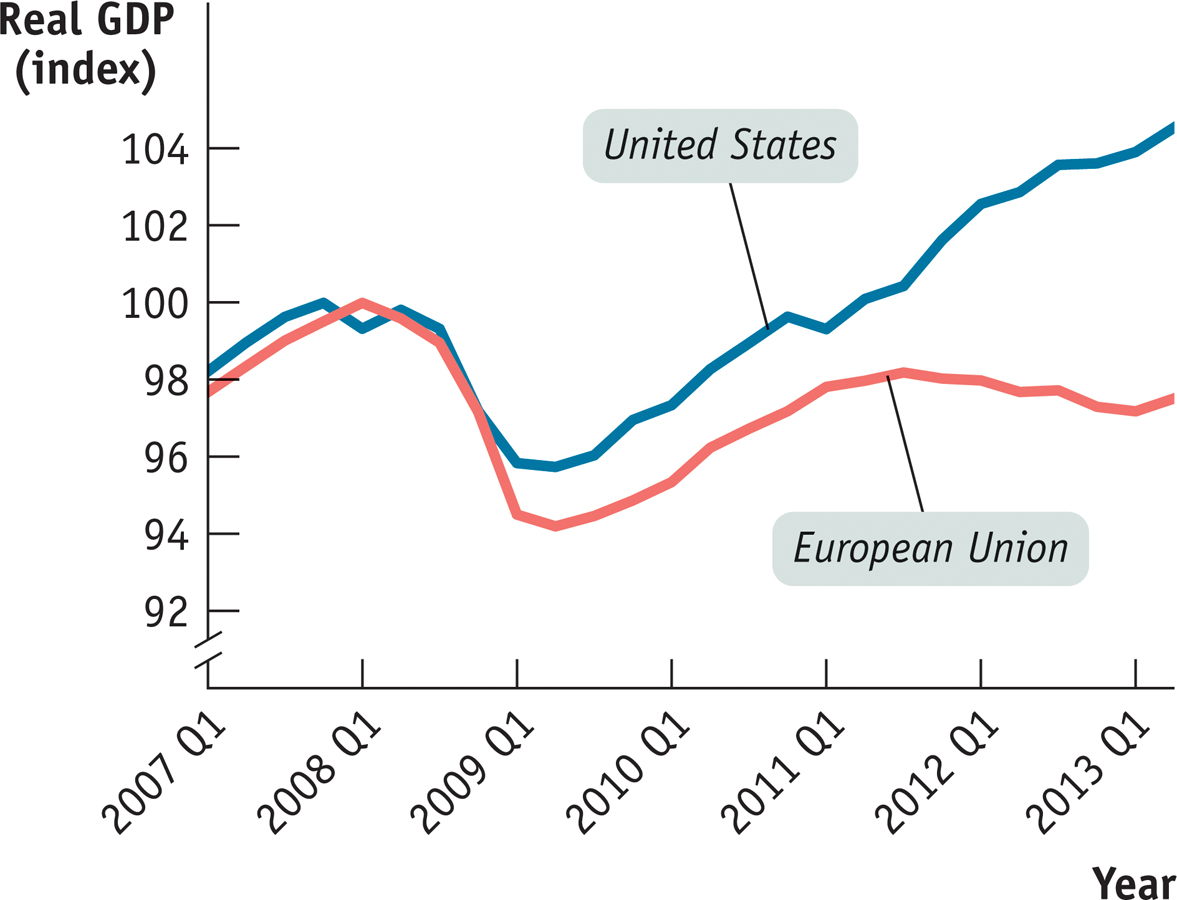

Figure 42-4 shows real GDP in the United States and the European Union, the world’s two largest economies, during the crisis and aftermath, with the peak pre-

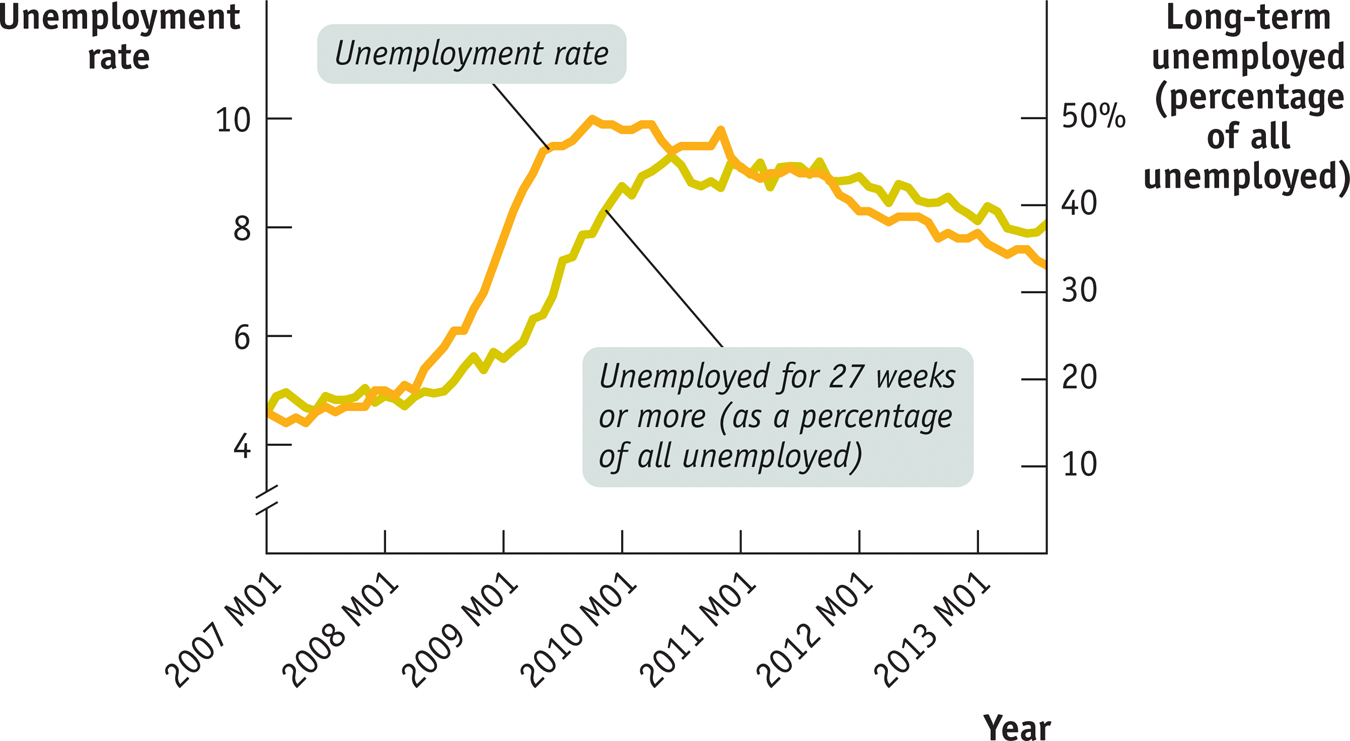

The severe slump and the slow recovery were very bad news for workers, since a healthy job market depends on an economy growing fast enough to accommodate both a growing workforce and rising productivity. Figure 42-5 shows two indicators of unemployment in the United States—

This outcome was, sad to say, about what one should have expected given the severity of the initial financial shock and the historical experience with such shocks.

Aftershocks in Europe

One important factor bedeviling hopes for recovery was the emergence of special difficulties in several European nations.

The 2008 crisis was caused by problems with private debt, mainly home loans, which then triggered a crisis of confidence in banks. In 2011 and 2012, fears of a second crisis were focused on public debt, specifically the public debts of Southern European countries plus Ireland.

Europe’s troubles first surfaced in Greece, a country with a long history of fiscal irresponsibility. In late 2009, it was revealed that a previous Greek government had understated the size of the budget deficits and the amount of government debt, prompting lenders to refuse further loans to Greece. Other European countries provided emergency loans to the Greek government in return for harsh budget cuts. But these budget cuts depressed the Greek economy, and by late 2011 there was general agreement that Greece could not pay back its debts in full.

By itself, this was probably a manageable shock for the European economy since Greece accounts for less than 3% of European GDP. Unfortunately, foot-

Spain also ran into trouble, the result of fallout from the 2008 crisis. It suffered a housing bubble between 2000 and 2007 that eventually burst, leading to a deep economic slump that depressed tax receipts and caused large budget deficits. There were worries that the Spanish government might have to spend large amounts bailing out banks. As a result, investors began to worry about the solvency of the government and a possible default, driving up interest rates.

Italy’s government also faced insolvency fears in 2010 because in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, investors feared that the Italian economy was growing too slowly to generate enough tax revenue to repay its public debt. These doubts drove up interest rates on Italian public debt, in turn creating a vicious circle: higher interest payments, caused by fears about Italian government solvency, worsened Italy’s fiscal position even further and pushed it closer to the edge.

Heading into 2014, the growth rate of real GDP in Greece, Spain, and Italy is forecast to be slightly positive for the first time since the crisis began. However, the level of real GDP in these countries remains well below pre-

The Stimulus–Austerity Debate

The persistence of economic difficulties after the 2008 financial crisis led to fierce debates about appropriate policy responses. Broadly speaking, economists and policy makers were divided as to whether the situation called for more fiscal stimulus—

The proponents of more stimulus pointed to the continuing poor performance of major economies, arguing that the combination of high unemployment and relatively low inflation clearly pointed to the need for expansionary policies. And since monetary policy was limited by the zero bound on interest rates, stimulus proponents advocated expansionary fiscal policy to fill the gap.

The austerity camp took a very different view. Strongly influenced by the solvency troubles of Greece, Ireland, Spain, and Italy, they argued that the common source of all the problems were high levels of government deficits and debts. In their view, countries like the United States that continued to run large government deficits several years after the 2008 crisis were at risk of suffering a similar loss of investor confidence in their ability to repay their debts. Moreover, austerity advocates claimed that cuts in government spending would not actually be contractionary because they would improve investor confidence and keep interest rates on government debt low.

Each side of the debate argued that recent experience refuted the other side’s claims. Austerity proponents argued that the persistence of high unemployment despite the fiscal stimulus programs adopted by the United States and other major economies in 2009 showed that stimulus doesn’t work. Stimulus advocates argued that these programs were simply inadequate in size, pointing out that many economists had warned of their inadequacy from the start.

Stimulus advocates further argued that warnings about the dangers of deficits were overblown, that far from rising, borrowing costs for Japan, the United States, and Britain—

At the time of writing, neither side was giving much ground. Clearly, any resolution of the debate would hinge on future economic developments and how they were interpreted.

The Lesson of the Post-Crisis Slump

Almost all major economies had great difficulty dealing with the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis—

Clearly, then, the best way to avoid the terrible problems that arise after a financial crisis is not to have a crisis in the first place. How can you do that? In part, one might hope, through better regulation of financial institutions.

Regulation in the Wake of the Crisis

By late 2009, interventions by governments and central banks around the world had restored calm to financial markets. However, huge damage had been done to the global economy.

The banking crisis of 2008 demonstrated, all too clearly, that financial regulation is a continuing process—

So what changes will the most recent crisis bring? One thing that became all too clear in the 2008 crisis was that the traditional scope of banking regulation was too narrow. Regulating only depository institutions was clearly inadequate in a world in which a large part of banking, properly understood, is undertaken by the shadow banking sector.

In the aftermath of the crisis, then, an overhaul of financial regulation was clearly needed. And in 2010 the U.S. Congress passed the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act—

- Consumer protection

- Derivatives regulation

- Regulation of shadow banks

- Resolution authority over nonbank financial institutions that face bankruptcy

1. Consumer ProtectionOne factor in the financial crisis was the fact that many borrowers accepted offers they didn’t understand, such as mortgages that were easy to pay in the first two years but required sharply higher payments later on. In an effort to limit future abuses, the new law creates a special office, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, dedicated to policing financial industry practices and protecting borrowers.

2. Derivatives RegulationAnother factor in the crisis was the proliferation of derivatives, complex financial instruments that were supposed to help spread risk but arguably simply concealed it. Under the new law, most derivatives have to be bought and sold in open, transparent markets, hopefully limiting the extent to which financial players can take on invisible risk.

3. Regulation Of Shadow BanksA key element in the financial crisis, as we’ve seen, was the rise of institutions that didn’t fit the conventional definition of a bank but played the role of banks and created the risk of a banking crisis. How can regulation be extended to such institutions?

Dodd-

4. Resolution AuthorityThe events of 2008 made it clear that governments would often feel the need to guarantee a wide range of financial institution debts in a crisis, not just deposits. Yet how can this be done without creating huge incentive problems, motivating financial institutions to undertake overly risky behavior in the knowledge that they will be bailed out by the government if they get into trouble?

Part of the answer is to empower the government to seize control of financial institutions that require a bailout, the way it already does with failing commercial banks and thrifts. This new power, known as resolution authority, should be viewed as solving a problem that seemed acute in early 2009, when several major financial institutions were teetering on the brink. Yet it wasn’t clear whether Washington had the legal authority to orchestrate a rescue that was fair to taxpayers.

It has been several years since the crisis ended and Dodd-

- How will these regulations be worked into the international financial system? Will other nations adopt similar policies? If they do, how will conflicts among different national policies be resolved?

- Will these regulations do the trick? Post-

1930s bank regulation produced decades of stability, but will that happen again? Or will the new system fail in the face of a serious test?

Nobody knows the answers to these questions. We’ll just have to continue to wait and see.

42

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

Which of the following are examples of maturity transformations? Which are subject to a bank-

run- like phenomenon in which fear of a failure becomes a self- fulfilling prophecy? Explain. -

a. You sell tickets to a lottery in which each ticket holder has a chance of winning a $10,000 jackpot.

This is not an example of maturity transformation because no short-term liabilities are being turned into long-term assets. So it is not subject to a bank run. -

b. Dana borrows on her credit card to pay her living expenses while she takes a year-

long course to upgrade her job skills. Without a better- paying job, she will not be able to pay her accumulated credit card balance. This is an example of maturity transformation: Dana incurs a short-term liability, credit card debt, to fund the acquisition of a long-term asset, better job skills. It can result in a bank-run-like phenomenon if her credit card lender becomes fearful of her ability to repay and stops lending to her. If this happens, she will not be able to finish her course and, as a result, will not be able to get the better job that would allow her to pay off her credit card loans. -

c. An investment partnership invests in office buildings. Partners invest their own funds and can redeem them only by selling their partnership share to someone else.

This is not an example of maturity transformation because there are no short-term liabilities. The partnership itself has no obligation to repay an individual partner’s investment and so has no liabilities, short term or long term. -

d. The local student union savings bank offers checking accounts to students and invests those funds in student loans.

This is an example of maturity transformation: the checking accounts are short-term liabilities of the student union savings bank, and the student loans are long-term assets.

-

In November 2011, the government of France announced that it was reducing its forecast for economic growth in 2012. It was also reducing its estimates of tax revenue for 2012, since a weaker economy would mean smaller tax receipts. To offset the effect of lower revenue on the budget deficit, the government also announced a new package of tax increases and spending cuts. Which side of the stimulus–

austerity debate was France taking? According to standard macroeconomics, a government should adopt expansionary policies to increase aggregate demand to address an economic slump. France, however, did just the opposite, responding to a weaker economy with a contractionary fiscal policy that would make the economy even weaker. This shows that the French government had adopted the austerity view, believing that it was more important to try to assure markets of its solvency than to support the economy.Why does the use of short-

term borrowing and being outside of the lender- of- last- resort system make shadow banks vulnerable to events similar to bank runs? Because shadow banks like Lehman relied on short-term borrowing to fund their operations, fears about their soundness could quickly lead lenders to immediately cut off their credit and force them into failure. And without membership in the lender-of-last-resort system, shadow banks like Lehman could not borrow from the Federal Reserve to make up for the short-term loans it had lost.How do you think the crisis of 2008 would have been mitigated if there had been no shadow banking sector but only the formal depository banking sector?

If there had been only a formal depository banking sector, several factors would have mitigated the potential and scope of a banking crisis. First, there would have been no repo financing; the only short-term liabilities would have been customers’ deposits, and these would have been largely covered by deposit insurance. Second, capital requirements would have reduced banks’ willingness to take on excessive risk, such as holding onto subprime mortgages. Also, direct oversight by the Federal Reserve would have prevented so much concentration of risk within the banking sector. Finally, depository banks are within the lender-of-last-resort system; as a result, depository banks had another layer of protection against the fear of depositors and other creditors that they couldn’t meet their obligations. All of these factors would have reduced the potential and scope of a banking crisis.Describe the incentive problem facing the U.S. government in responding to the 2007–

2009 crisis with respect to the shadow banking sector. How did the Dodd- Frank Act attempt to address those incentive problems? Because the shadow banking sector had become such a critical part of the U.S. economy, the crisis of 2008 made it clear that in the event of another crisis, the government would need to guarantee a wide range of financial institution debts, including those of shadow banks (in addition to those of depository banks). The result was an incentive problem: shadow banks would be able to take more risk, knowing that the government would bail them out in the event of a meltdown. To counteract this, the Dodd-Frank Act gave the government the power to regulate “systemically important” shadow banks (those likely to wreak havoc on the economy should they fail) in order to reduce their risk taking. It also gave the government the power to seize control of failing shadow banks in a way that was fair to taxpayers and and that did not enrich the bankers involved.

Multiple-

Question

What makes a shadow bank different from a depository bank?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

The conversion of short-

term liabilities into long- term assets is called A. B. C. D. E. Question

People in a coastal community believe housing prices in their area have been pushed to unreasonably high levels due to expectations of rising demand for housing by retiring baby boomers. This situation is termed

A. B. C. D. E. Question

A severe banking crisis typically leads to

A. B. C. D. E. Question

When a borrower is left with high debt but diminished assets this situation is called

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

Question 1.1

Why does a banking crisis normally lead to a deep recession?