1.4 46Exchange Rates and Macroeconomic Policy

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The meaning and purpose of devaluation and revaluation of a currency under a fixed exchange rate regime

The meaning and purpose of devaluation and revaluation of a currency under a fixed exchange rate regime

Why open-

Why open-economy considerations affect macroeconomic policy under floating exchange rates

When the euro was created in 1999, there were celebrations across the nations of Europe—

Why did Britain say no? Part of the answer was national pride: for example, if Britain gave up the pound, it would also have to give up currency that bears the portrait of the queen. But there were also serious economic concerns about giving up the pound in favor of the euro.

British economists who favored adoption of the euro argued that if Britain used the same currency as its neighbors, the country’s international trade would expand and its economy would become more productive. But other economists pointed out that adopting the euro would take away Britain’s ability to have an independent monetary policy and might lead to macroeconomic problems.

As this discussion suggests, the fact that modern economies are open to international trade and capital flows adds a new level of complication to our analysis of macroeconomic policy. Let’s now look at these three policy issues raised by open-

- Devaluation and revaluation of fixed exchange rates

- Monetary policy under a floating exchange rate regime

- International business cycles

Devaluation and Revaluation of Fixed Exchange Rates

Historically, fixed exchange rates haven’t been permanent commitments. Sometimes countries with a fixed exchange rate switch to a floating rate. In other cases, they retain a fixed exchange rate but change the target exchange rate. Such adjustments in the target were common during the Bretton Woods era described in the upcoming Economics in Action. For example, in 1967 Britain changed the exchange rate of the pound against the U.S. dollar from US$2.80 per £1 to US$2.40 per £1. Another example is Argentina, which maintained a fixed exchange rate against the dollar from 1991 to 2001, but switched to a floating exchange rate at the end of 2001.

A devaluation is a reduction in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime.

A revaluation is an increase in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime.

A reduction in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime is called devaluation. As we’ve already learned, a depreciation is a downward move in a currency. A devaluation is a depreciation that is due to a revision in a fixed exchange rate target. An increase in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime is called a revaluation.

A devaluation, like any depreciation, makes domestic goods cheaper in terms of foreign currency, which leads to higher exports. At the same time, it makes foreign goods more expensive in terms of domestic currency, which reduces imports. The effect is to increase the balance of payments on the current account. Similarly, a revaluation makes domestic goods more expensive in terms of foreign currency, which reduces exports, and makes foreign goods cheaper in domestic currency, which increases imports. So a revaluation reduces the balance of payments on the current account.

Devaluations and revaluations serve two purposes under a fixed exchange rate regime. First, they can be used to eliminate shortages or surpluses in the foreign exchange market. For example, in 2010, some economists and politicians were urging China to revalue the yuan because they believed that China’s exchange rate policy unfairly aided Chinese exports. China eventually took action at the end of 2011, discontinuing much of their exchange rate intervention and allowing the yuan to gradually appreciate in value.

Second, devaluation and revaluation can be used as tools of macroeconomic policy. A devaluation, by increasing exports and reducing imports, increases aggregate demand. So a devaluation can be used to reduce or eliminate a recessionary gap. A revaluation has the opposite effect, reducing aggregate demand. So a revaluation can be used to reduce or eliminate an inflationary gap.

FROM BRETTON WOODS TO THE EURO

In 1944, while World War II was still raging, representatives of the Allied nations met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to establish a postwar international monetary system of fixed exchange rates among major currencies. The system was highly successful at first, but it broke down in 1971. After a confusing interval during which policy makers tried unsuccessfully to establish a new fixed exchange rate system, by 1973 most economically advanced countries had moved to floating exchange rates.

In Europe, however, many policy makers were unhappy with floating exchange rates, which they believed created too much uncertainty for business. From the late 1970s onward they tried several times to create a system of more or less fixed exchange rates in Europe, culminating in an arrangement known as the Exchange Rate Mechanism. (The Exchange Rate Mechanism was, strictly speaking, a “target zone” system—

And in 1991 they agreed to move to the ultimate in fixed exchange rates: a common European currency, the euro. To the surprise of many analysts, they pulled it off: today most of Europe has abandoned national currencies for the euro.

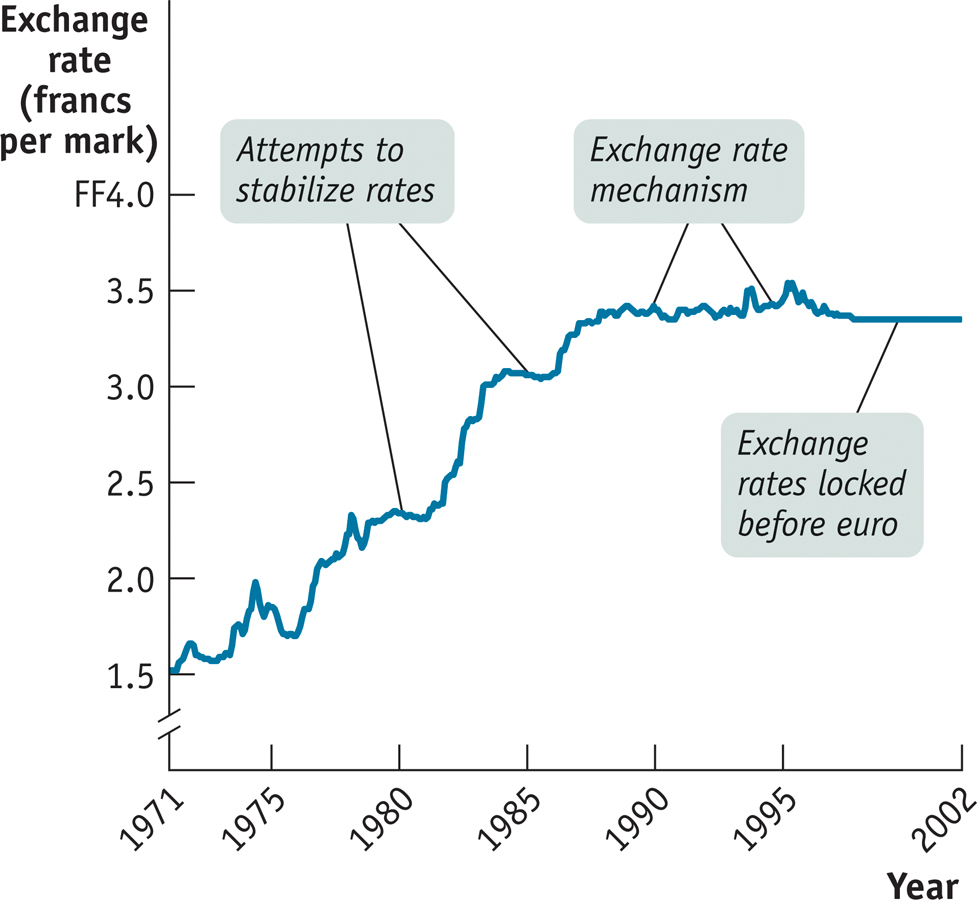

Figure 46-1 illustrates the history of European exchange rate arrangements. It shows the exchange rate between the French franc and the German mark, measured as francs per mark, from 1971 until their replacement by the euro. The exchange rate fluctuated widely at first. The “plateaus” you can see in the data—

The Exchange Rate Mechanism, after a couple of false starts, became effective in 1987, stabilizing the exchange rate at about 3.4 francs per mark. (The wobbles in the early 1990s reflect two currency crises—

In 1999 the exchange rate was “locked”—no further fluctuations were allowed as the countries prepared to switch from francs and marks to the euro. At the end of 2001, the franc and the mark ceased to exist.

The transition to the euro has not been without costs. Countries that adopted the euro sacrificed some important policy tools: they could no longer tailor monetary policy to their specific economic circumstances or lower their costs relative to other European nations simply by letting their currencies depreciate.

In 2013, the euro area remained under stress as many countries struggled to recover from severe recession following the 2008 financial crisis. Several nations—

Monetary Policy Under a Floating Exchange Rate Regime

Under a floating exchange rate regime, a country’s central bank retains its ability to pursue independent monetary policy: it can increase aggregate demand by cutting the interest rate or decrease aggregate demand by raising the interest rate. But the exchange rate adds another dimension to the effects of monetary policy. To see why, let’s return to the hypothetical country of Genovia as discussed in the preceding module and ask what happens if the central bank cuts the interest rate.

Just as in a closed economy, a lower interest rate leads to higher investment spending and higher consumer spending. But the decline in the interest rate also affects the foreign exchange market. Foreigners have less incentive to move funds into Genovia because they will receive a lower rate of return on their loans. As a result, they have less need to exchange U.S. dollars for genos, so the demand for genos falls. At the same time, Genovians have more incentive to move funds abroad because the rate of return on loans at home has fallen, making investments outside the country more attractive. Thus, they need to exchange more genos for U.S. dollars and the supply of genos rises.

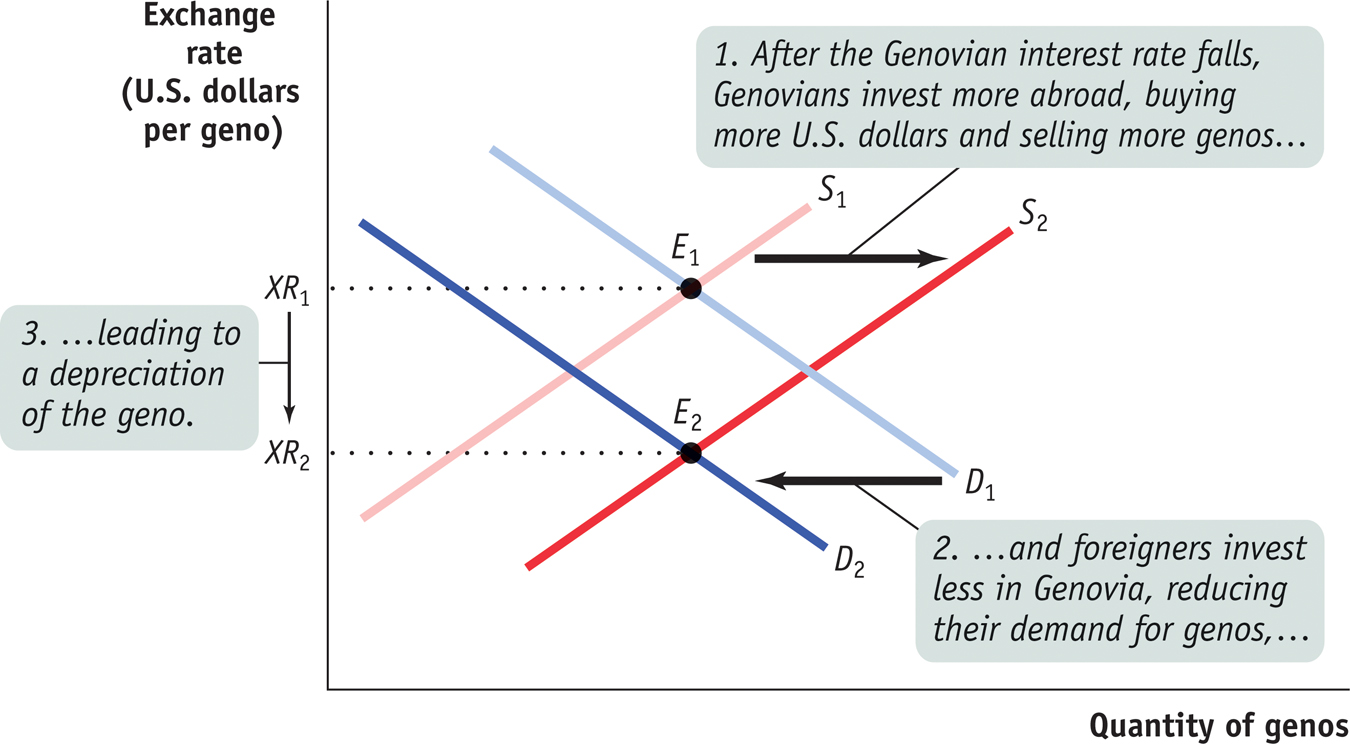

Figure 46-2 shows the effect of an interest rate reduction on the foreign exchange market. The demand curve for genos shifts leftward, from D1 to D2, and the supply curve shifts rightward, from S1 to S2. The equilibrium exchange rate, as measured in U.S. dollars per geno, falls from XR1 to XR2. That is, a reduction in the Genovian interest rate causes the geno to depreciate.

The depreciation of the geno, in turn, affects aggregate demand. We’ve already seen that a devaluation—

In other words, monetary policy under floating rates has effects beyond those we’ve described in looking at closed economies.

In a closed economy, a reduction in the interest rate leads to a rise in aggregate demand because it leads to more investment spending and consumer spending.

In an open economy with a floating exchange rate, the interest rate reduction leads to increased investment spending and consumer spending, but it also increases aggregate demand in another way: it leads to a currency depreciation, which increases exports and reduces imports, further increasing aggregate demand.

International Business Cycles

Up to this point, we have discussed macroeconomics, even in an open economy, as if all demand changes or shocks originated from the domestic economy. In reality, however, economies sometimes face shocks coming from abroad. For example, recessions in the United States have historically led to recessions in Mexico.

The key point is that changes in aggregate demand affect the demand for goods and services produced abroad as well as at home: other things equal, a recession leads to a fall in imports and an expansion leads to a rise in imports. And one country’s imports are another country’s exports. This link between aggregate demand in different national economies is one reason business cycles in different countries sometimes—

The extent of this link depends, however, on the exchange rate regime. To see why, think about what happens if a recession abroad reduces the demand for Genovia’s exports. A reduction in foreign demand for Genovian goods and services is also a reduction in demand for genos on the foreign exchange market. If Genovia has a fixed exchange rate, it responds to this decline with exchange market intervention.

But if Genovia has a floating exchange rate, the geno depreciates. Because Genovian goods and services become cheaper to foreigners when the demand for exports falls, the quantity of goods and services exported doesn’t fall by as much as it would under a fixed rate. At the same time, the fall in the geno makes imports more expensive to Genovians, leading to a fall in imports. Both effects limit the decline in Genovia’s aggregate demand compared to what it would have been under a fixed exchange rate regime.

One of the virtues of floating exchange rates, according to their advocates, is that they help insulate countries from recessions originating abroad. This theory looked pretty good in the early 2000s: Britain, with a floating exchange rate, managed to stay out of a recession that affected the rest of Europe, and Canada, which also has a floating rate, suffered a less severe recession than the United States.

In 2008, however, the financial crisis that began in the United States produced a recession in virtually every country. In this case, it appears that the international linkages between financial markets were much stronger than any insulation from overseas disturbances provided by floating exchange rates.

46

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

Look at Figure 46-1. Where do you see devaluations and revaluations of the franc against the mark?

The devaluations and revaluations most likely occurred in those periods when there was a sudden change in the franc–mark exchange rate: 1974, 1976, the early 1980s, 1986, and 1993–1994.In the late 1980s, Canadian economists argued that the high interest rate policies of the Bank of Canada weren’t just causing high unemployment—

they were also making it hard for Canadian manufacturers to compete with U.S. manufacturers. Explain this complaint, using our analysis of how monetary policy works under floating exchange rates. The high Canadian interest rates caused an increase in capital inflows to Canada. To obtain assets that yielded a relatively high interest rate in Canada, investors first had to obtain Canadian dollars. The increase in the demand for the Canadian dollar caused the Canadian dollar to appreciate. This appreciation of the Canadian currency raised the price of Canadian goods to foreigners (measured in terms of the foreign currency). This made it more difficult for Canadian firms to compete in other markets.

Multiple-

Question

Devaluation of a currency occurs when which of the following happens?

I. The supply of a currency with a floating exchange rate increases.

II. The demand for a currency with a floating exchange rate decreases.

III. The government decreases the fixed exchange rate.A. B. C. D. E. Question

Devaluation of a currency will lead to which of the following?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Devaluation of a currency is used to achieve which of the following?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Monetary policy that reduces the interest rate will do which of the following?

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Which of the following will happen in a country if a trading partner’s economy experiences a recession?

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

Explain how a floating exchange rate system can help insulate a country from recessions abroad.

A reduction in foreign demand for the country’s domestic goods and services leads to a reduction in demand for the domestic currency. With a floating exchange rate, the currency depreciates. This makes domestic goods and services cheaper, so exports don’t fall by as much as they would have, and it makes imports more expensive, leading to a fall in imports. Both effects limit the decline in domestic aggregate demand.