Macroeconomics: Events and Ideas

Macroeconomics: Events and Ideas

SECTION14

- Module 47: History and Alternative Views of Macroeconomics

- Module 48: The Modern Macroeconomic Consensus

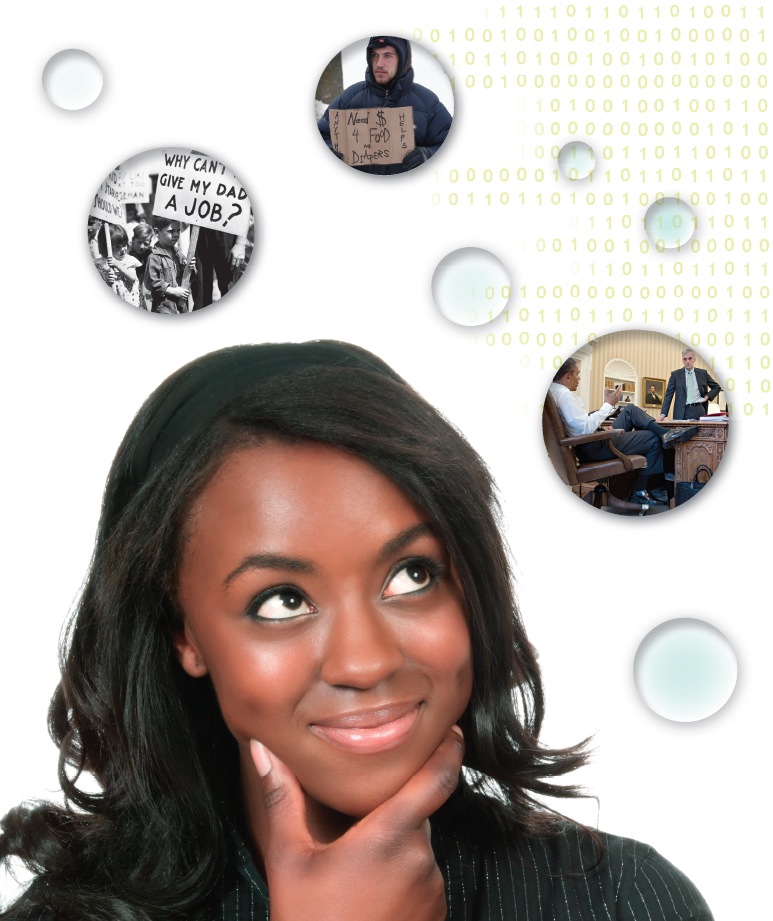

A TALE OF TWO SLUMPS

In November 2002, the Federal Reserve held a special conference to honor Milton Friedman on the occasion of his 90th birthday. Among those delivering tributes was Ben Bernanke, then a member of the Board of Governors, who later served as Fed Chairman. In his tribute, Bernanke surveyed Friedman’s intellectual contributions, with particular focus on the argument made by Friedman and his collaborator Anna Schwartz that the Great Depression of the 1930s could have been avoided if only the Fed had done its job properly.

At the close of his talk, Bernanke directly addressed Friedman and Schwartz, who were sitting in the audience: “Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an offi cial representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.”

Today, in the aftermath of a devastating financial crisis that continues to inflict high unemployment, those words ring somewhat hollow. Avoiding severe economic downturns, it turned out, wasn’t as easy as Friedman, Schwartz, and Bernanke had believed. Yet, as bad as they were, the crisis of 2008 and its aftermath were less devastating than the Great Depression.

It can be reasonably argued that part of the reason was that macroeconomics had evolved in the 78 years from 1930 to 2008. As a result, policy makers knew more about the causes of depressions and how to fight them than they did during the Great Depression.

In this section we’ll trace the development of macroeconomic ideas over the past 80 years. As we’ll see, this development has been strongly influenced by economic events, from the Great Depression of the 1930s, to the stagflation of the 1970s, to the surprising period of economic stability achieved between 1985 and 2007. And as we’ll also see, the process continues, as the economic diffi-culties since 2008 have spurred many macroeconomists to rethink what they thought they knew.