1.3 3Comparative Advantage and Trade

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

How trade leads to gains for an individual or an economy

How trade leads to gains for an individual or an economy

The difference between absolute advantage and comparative advantage

The difference between absolute advantage and comparative advantage

How comparative advantage leads to gains from trade in the global marketplace

How comparative advantage leads to gains from trade in the global marketplace

Gains from Trade

In a market economy, individuals engage in trade: they provide goods and services to others and receive goods and services in return.

A family could try to take care of all its own needs—

There are gains from trade: people can get more of what they want through trade than they could if they tried to be self-

The reason we have an economy is that there are gains from trade: by dividing tasks and trading, two people (or 7 billion people) can each get more of what they want than they could get by being self-

The advantages of specialization, and the resulting gains from trade, were the starting point for Adam Smith’s 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, which many regard as the beginning of economics as a discipline. Smith’s book begins with a description of an eighteenth-

One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a particular business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations…. Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-

The same principle applies when we look at how people divide tasks among themselves and trade in an economy. The economy, as a whole, can produce more when each person specializes in a task and trades with others.

The benefits of specialization are the reason a person typically focuses on the production of only one type of good or service. It takes many years of study and experience to become a doctor; it also takes many years of study and experience to become a commercial airline pilot. Many doctors might have the potential to become excellent pilots, and vice versa, but it is very unlikely that anyone who decided to pursue both careers would be as good a pilot or as good a doctor as someone who specialized in only one of those professions. So it is to everyone’s advantage when individuals specialize in their career choices.

Markets are what allow a doctor and a pilot to specialize in their respective fields. Because markets for commercial flights and for doctors’ services exist, a doctor is assured that she can find a flight and a pilot is assured that he can find a doctor. As long as individuals know that they can find the goods and services that they want in the market, they are willing to forgo self-

Comparative Advantage and Gains from Trade

One of the most important insights in all of economics is that there are gains from trade—

How can we model the gains from trade? Let’s stay with our aircraft example and once again imagine that the United States is a one-

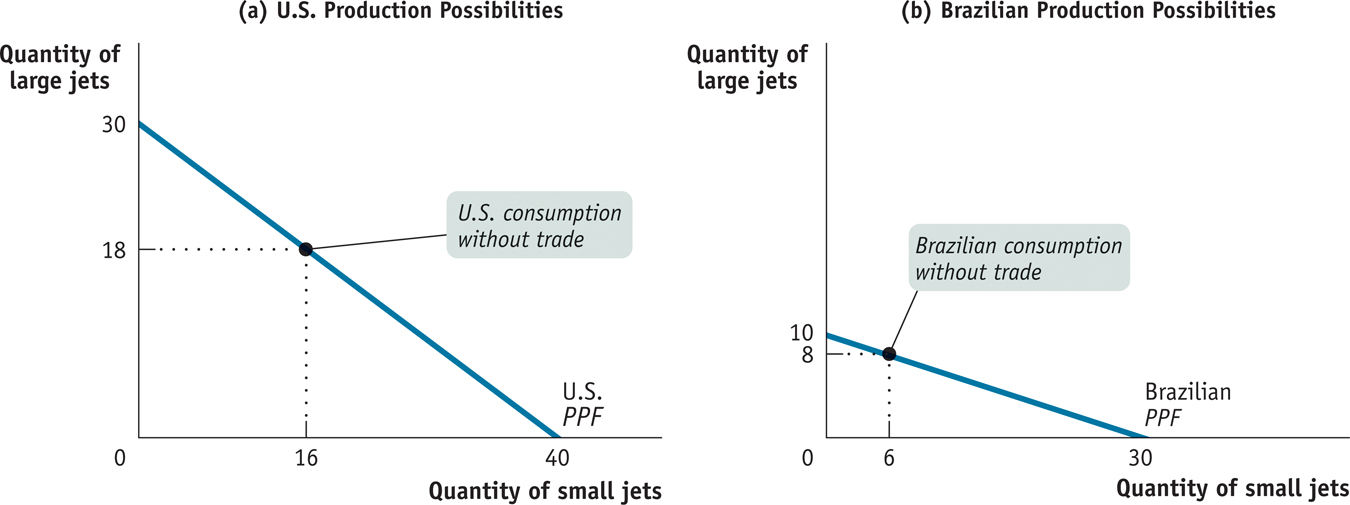

Both countries could produce either kind of jet. But as we’ll see in a moment, they can gain by producing different things and trading with each other. Let’s return to the simpler case of straight-

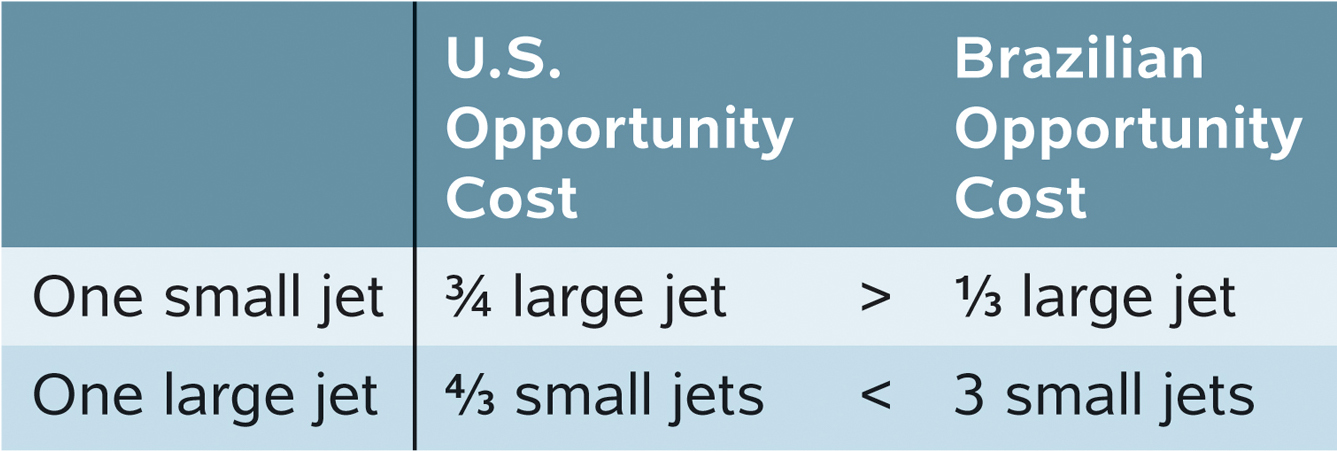

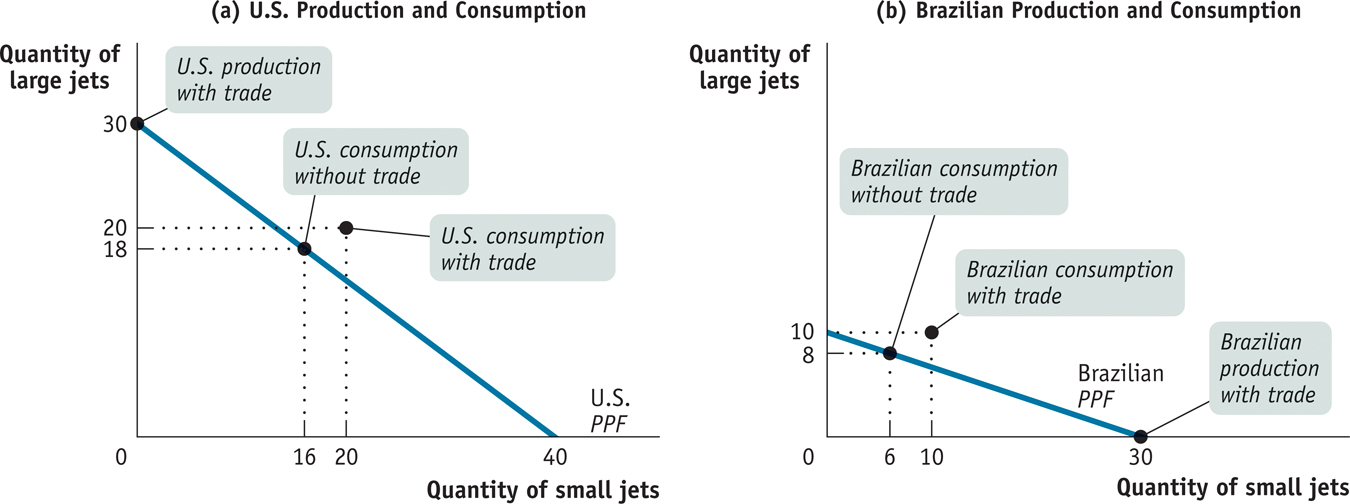

Panel (b) of Figure 3-1 shows Brazil’s production possibilities. Like the United States, Brazil’s production possibility curve is a straight line. Brazil’s production possibility curve has a constant slope of −⅓. Brazil can’t produce as much of anything as the United States can: at most it can produce 30 small jets or 10 large jets. But it is relatively better at manufacturing small jets than the United States. While the United States sacrifices ¾ of a large jet per small jet produced, for Brazil the opportunity cost of a small jet is only ⅓ of a large jet. Table 3-1 summarizes the two countries’ opportunity costs of small jets and large jets.

3-1

U.S. and Brazilian Opportunity Costs of Small Jets and Large Jets

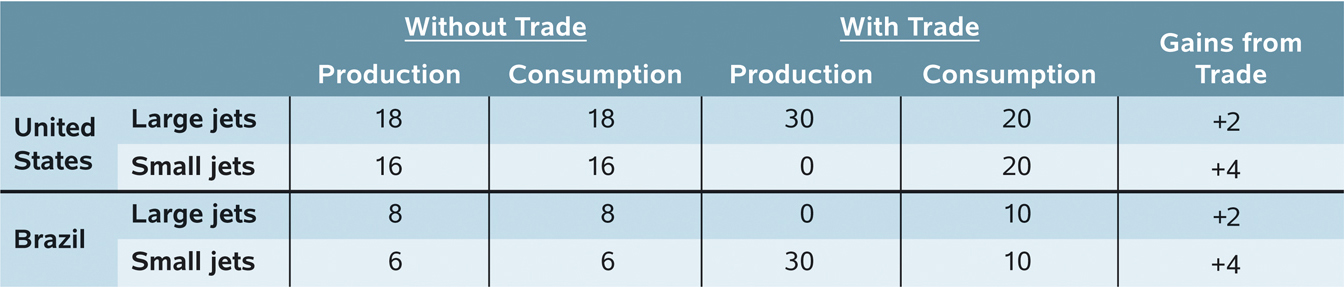

Now, the United States and Brazil could each choose to make their own large and small jets, not trading any airplanes at all. Let’s suppose that the two countries start out this way and make the consumption choices shown in Figure 3-1: in the absence of trade, the United States produces and consumes 16 small jets and 18 large jets per year, while Brazil produces and consumes 6 small jets and 8 large jets per year.

But is this the best the two countries can do? No, it isn’t. Given that the two producers—

Table 3-2 shows how such a deal works: the United States specializes in the production of large jets, manufacturing 30 per year, and sells 10 to Brazil. Meanwhile, Brazil specializes in the production of small jets, producing 30 per year, and sells 20 to the United States. The result is shown in Figure 3-2. The United States now consumes more of both small jets and large jets than before: instead of 16 small jets and 18 large jets, it now consumes 20 small jets and 20 large jets. Brazil also consumes more, going from 6 small jets and 8 large jets to 10 small jets and 10 large jets. As Table 3-2 also shows, both the United States and Brazil reap gains from trade, consuming more of both types of plane than they would have without trade.

3-2

How the United States and Brazil Gain from Trade

Both countries are better off when they each specialize in what they are good at and trade. It’s a good idea for the United States to specialize in the production of large jets because its opportunity cost of a large jet is smaller than Brazil’s:  . Correspondingly, Brazil should specialize in the production of small jets because its opportunity cost of a small jet is smaller than the United States: ⅓ < ¾.

. Correspondingly, Brazil should specialize in the production of small jets because its opportunity cost of a small jet is smaller than the United States: ⅓ < ¾.

A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good or service if its opportunity cost of producing the good or service is lower than other countries’.

What we would say in this case is that the United States has a comparative advantage in the production of large jets and Brazil has a comparative advantage in the production of small jets. A country has a comparative advantage in producing something if the opportunity cost of that production is lower for that country than for other countries. The same concept applies to firms and people: a firm or an individual has a comparative advantage in producing something if its, his, or her opportunity cost of production is lower than for others.

One point of clarification before we proceed further. You may have wondered why the United States traded 10 large jets to Brazil in return for 20 small jets. Why not some other deal, like trading 10 large jets for 12 small jets? The answer to that question has two parts. First, there may indeed be other trades that the United States and Brazil might agree to. Second, there are some deals that we can safely rule out—

To understand why, reexamine Table 3-1 and consider the United States first. Without trading with Brazil, the U.S. opportunity cost of a small jet is ¾ of a large jet. So it’s clear that the United States will not accept any trade that requires it to give up more than ¾ of a large jet for a small jet. Trading 10 large jets in return for 12 small jets would require the United States to pay an opportunity cost of 10/12 = 5/6 of a large jet for a small jet. Because 5/6 > ¾, this is a deal that the United States would reject. Similarly, Brazil won’t accept a trade that gives it less than ⅓ of a large jet for a small jet.

The point to remember is that the United States and Brazil will be willing to trade only if the “price” of the good each country obtains in the trade is less than its own opportunity cost of producing the good domestically. Moreover, this is a general statement that is true whenever two parties—

While our story clearly simplifies reality, it teaches us some very important lessons that apply to the real economy, too.

First, the model provides a clear illustration of the gains from trade: through specialization and trade, both countries produce more and consume more than if they were self-

Second, the model demonstrates a very important point that is often overlooked in real-

A country has an absolute advantage in producing a good or service if the country can produce more output per worker than other countries. Likewise, an individual has an absolute advantage in producing a good or service if he or she is better at producing it than other people. Having an absolute advantage is not the same thing as having a comparative advantage.

Crucially, in our example it doesn’t matter if, as is probably the case in real life, U.S. workers are just as good as or even better than Brazilian workers at producing small jets. Suppose that the United States is actually better than Brazil at all kinds of aircraft production. In that case, we would say that the United States has an absolute advantage in both large-

But we’ve just seen that the United States can indeed benefit from trading with Brazil because comparative, not absolute, advantage is the basis for mutual gain. It doesn’t matter whether it takes Brazil more resources than the United States to make a small jet; what matters for trade is that for Brazil the opportunity cost of a small jet is lower than the U.S. opportunity cost. So Brazil, despite its absolute disadvantage, even in small jets, has a comparative advantage in the manufacture of small jets. Meanwhile the United States, which can use its resources most productively by manufacturing large jets, has a comparative disadvantage in manufacturing small jets.

If comparative advantage were relevant only to airplane manufacturers, it might not be that interesting. However, the idea of comparative advantage applies to many activities in the economy. Perhaps its most important application is in trade—

RICH NATION, POOR NATION

Try taking off your clothes—

Why are these countries so much poorer than the United States? The immediate reason is that their economies are much less productive—firms in these countries are just not able to produce as much from a given quantity of resources as comparable firms in the United States or other wealthy countries. Why countries differ so much in productivity is a deep question—

But if the economies of these countries are so much less productive than ours, how is it that they make so much of our clothing? Why don’t we do it for ourselves?

The answer is “comparative advantage.” Just about every industry in Bangladesh is much less productive than the corresponding industry in the United States. But the productivity difference between rich and poor countries varies across goods; there is a very great difference in the production of sophisticated goods such as aircraft but not as great a difference in the production of simpler goods such as clothing. So Bangladesh’s position with regard to clothing production is like Brazil’s position with respect to producing smaller jets. While Brazil is not as good as the United States at making either small or large jets, producing smaller jets is what Brazil does comparatively well.

Although Bangladesh is at an absolute disadvantage compared with the United States in almost everything, it has a comparative advantage in clothing production. This means that both the United States and Bangladesh are able to consume more because they specialize in producing different things, with Bangladesh supplying our clothing and the United States supplying Bangladesh with more sophisticated goods.

Comparative Advantage and International Trade, in Reality

Look at the label on a manufactured good sold in the United States, and there’s a good chance you will find that it was produced in some other country. On the other side, many U.S. industries sell a large fraction of their output overseas.

Should all this international exchange of goods and services be celebrated, or is it cause for concern? Politicians and the public often question the desirability of international trade, arguing that the nation should produce goods for itself rather than buy them from foreigners. Industries around the world demand protection from foreign competition: Japanese farmers want to keep out American rice, American steelworkers want to keep out European steel. And these demands are often supported by public opinion.

Economists, however, have a very positive view of international trade. Why? Because they view it in terms of comparative advantage. As we learned from our example of U.S. large jets and Brazilian small jets, international trade benefits both countries. Each country can consume more than if it didn’t trade and remained self-

Sources of Comparative Advantage

International trade is driven by comparative advantage, but where does comparative advantage come from? Economists who study international trade have found three main sources of comparative advantage: international differences in climate, international differences in factor endowments, and international differences in technology.

Differences in ClimateIn general, differences in climate play a significant role in international trade. Tropical countries export tropical products like coffee, sugar, bananas, and shrimp. Countries in the temperate zones export crops like wheat and corn. Some trade is even driven by the difference in seasons between the northern and southern hemispheres: winter deliveries of Chilean grapes and New Zealand apples have become commonplace in U.S. and European supermarkets.

Differences in Factor EndowmentsCanada is a major exporter of forest products—

Forestland, like labor and capital, is a factor of production: an input used to produce goods and services. Due to history and geography, the mix of available factors of production differs among countries, providing an important source of comparative advantage.

Consider world trade in clothing. Clothing production is a labor-

Differences in TechnologyIn the 1970s and 1980s, Japan became by far the world’s largest exporter of automobiles, selling large numbers to the United States and the rest of the world. Japan’s comparative advantage in automobiles wasn’t the result of climate. Nor can it easily be attributed to differences in factor endowments: aside from a scarcity of land, Japan’s mix of available factors is quite similar to that in other advanced countries. Instead, Japan’s comparative advantage in automobiles was based on the superior production techniques developed by its manufacturers, which allowed them to produce more cars with a given amount of labor and capital than their American or European counterparts.

Japan’s comparative advantage in automobiles was a case of comparative advantage caused by differences in technology—

The causes of differences in technology are somewhat mysterious. Sometimes they seem to be based on knowledge accumulated through experience—

3

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

In Italy, an automobile can be produced by 8 workers in one day and a washing machine by 3 workers in one day. In the United States, an automobile can be produced by 6 workers in one day, and a washing machine by 2 workers in one day.

-

a. Which country has an absolute advantage in the production of automobiles? In washing machines?

The United States has an absolute advantage in automobile production because it takes fewer Americans (6) to produce a car in one day than it takes Italians (8). The United States also has an absolute advantage in washing machine production because it takes fewer Americans (2) to produce a washing machine in one day than it takes Italians (3). -

b. Which country has a comparative advantage in the production of washing machines? In automobiles?

In Italy the opportunity cost of a washing machine in terms of an automobile is ⅜. In other words, ⅜ of a car can be produced with the same number of workers and in the same time it takes to produce 1 washing machine. In the United States the opportunity cost of a washing machine in terms of an automobile is . In other words, ⅓ of a car can be produced with the same number of workers and in the same time it takes to produce 1 washing machine. Since ⅓ < ⅜, the United States has a comparative advantage in the production of washing machines: to produce a washing machine, only ⅓ of a car must be given up in the United States but ⅜ of a car must be given up in Italy. This means that Italy has a comparative advantage in automobiles. This can be checked as follows. The opportunity cost of an automobile in terms of a washing machine in Italy is

. In other words, ⅓ of a car can be produced with the same number of workers and in the same time it takes to produce 1 washing machine. Since ⅓ < ⅜, the United States has a comparative advantage in the production of washing machines: to produce a washing machine, only ⅓ of a car must be given up in the United States but ⅜ of a car must be given up in Italy. This means that Italy has a comparative advantage in automobiles. This can be checked as follows. The opportunity cost of an automobile in terms of a washing machine in Italy is  , equal to 2⅔. In other words, 2⅔ washing machines can be produced with the same number of workers and in the time it takes to produce 1 car in Italy. And the opportunity cost of an automobile in terms of a washing machine in the United States is

, equal to 2⅔. In other words, 2⅔ washing machines can be produced with the same number of workers and in the time it takes to produce 1 car in Italy. And the opportunity cost of an automobile in terms of a washing machine in the United States is  , equal to 3. In other words, 3 washing machines can be produced with the same number of workers and in the time it takes to produce 1 car in the United States.

, equal to 3. In other words, 3 washing machines can be produced with the same number of workers and in the time it takes to produce 1 car in the United States. -

c. What type of specialization results in the greatest gains from trade between the two countries?

The greatest gains are realized when each country specializes in producing the good for which it has a comparative advantage. Therefore, based on this example, the United States should specialize in washing machines and Italy should specialize in automobiles.

-

Using the numbers from Table 3-1, explain why the United States and Brazil are willing to engage in a trade of 10 large jets for 15 small jets.

At a trade of 10 U.S. large jets for 15 Brazilian small jets, Brazil gives up less for a large jet than it would if it were building large jets itself. Without trade, Brazil gives up 3 small jets for each large jet it produces. With trade, Brazil gives up only 1.5 small jets for each large jet from the United States. Likewise, the United States gives up less for a small jet than it would if it were producing small jets itself. Without trade, the United States gives up ¾ of a large jet for each small jet. With trade, the United States gives up only ⅔ of a large jet for each small jet from Brazil.

Multiple-

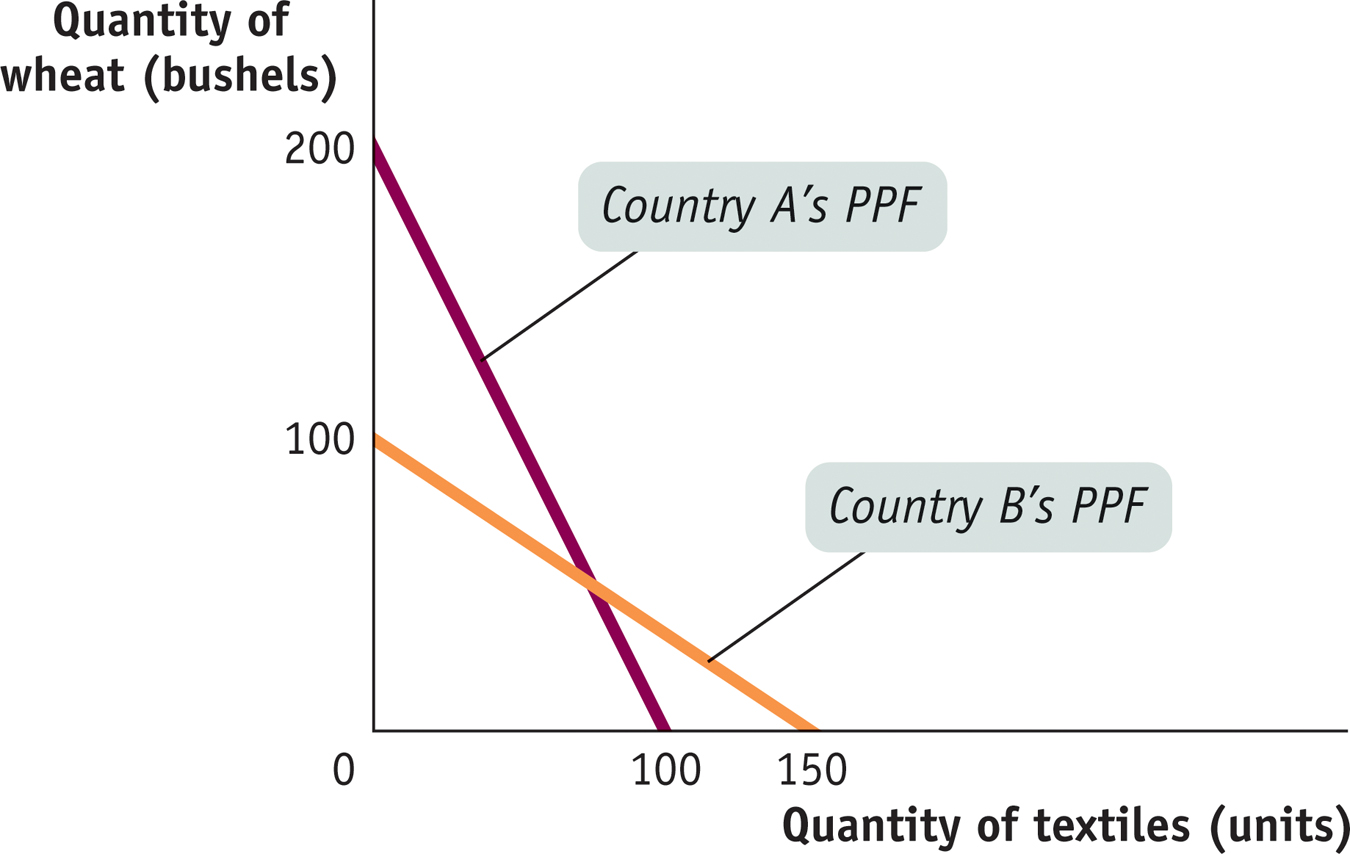

Refer to the graph below to answer the following questions.

Question

Use the graph to determine which country has an absolute advantage in producing each good.

Absolute advantage in wheat productionAbsolute advantage in textile productionA. B. C. D. E. Question

For Country A, the opportunity cost of a bushel of wheat is

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Use the graph to determine which country has a comparative advantage in producing each good.

Comparative advantage in wheat productionComparative advantage in textile productionA. B. C. D. E. Question

If the two countries specialize and trade, which of the choices below describes the countries’ imports?

Import WheatImport TextilesA. B. C. D. E. Question

What is the highest price Country B is willing to pay to buy wheat from Country A?

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

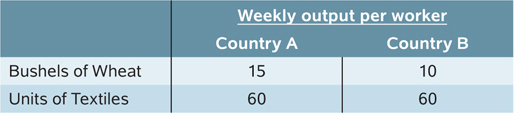

Refer to the table below to answer the following questions. These two countries are producing textiles and wheat using equal amounts of resources.

What is the opportunity cost of producing a bushel of wheat for each country?

Country A: opportunity cost of 1 bushel of wheat = 4 units of textiles

Country B: opportunity cost of 1 bushel of wheat = 6 units of textilesWhich country has the absolute advantage in wheat production?

Country A has an absolute advantage in the production of wheat (15 versus 10)Which country has the comparative advantage in textile production? Explain.

Country A: opportunity cost of 1 unit of textiles = ¼ bushel of wheat

Country B: opportunity cost of 1 unit of textiles = ⅙ bushel of wheat

Country B has the comparative advantage in textile production because it has a lower opportunity cost of producing textiles. (Alternate answer: Country B has the comparative advantage in the production of textiles because Country A has a comparative advantage in the production of wheat based on opportunity costs shown in part a.)

Back in the 1980s, when the U.S. economy seemed to be lagging behind that of Japan, commentators often warned that if we didn’t improve our productivity, we would soon have no comparative advantage in anything. What is wrong with this statement?

Back in the 1980s, when the U.S. economy seemed to be lagging behind that of Japan, commentators often warned that if we didn’t improve our productivity, we would soon have no comparative advantage in anything. What is wrong with this statement?

IT IS INACCURATE; THOSE COMMENTATORS MISUNDERSTOOD COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE. It happens all the time. Students, pundits, and politicians confuse comparative advantage with absolute advantage. What the commentators meant was that we would have no absolute advantage in anything—

IT IS INACCURATE; THOSE COMMENTATORS MISUNDERSTOOD COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE. It happens all the time. Students, pundits, and politicians confuse comparative advantage with absolute advantage. What the commentators meant was that we would have no absolute advantage in anything—

A country has an absolute advantage in producing a good or service if the country can produce more output per worker than other countries. Likewise, an individual has an absolute advantage in producing a good or service if he or she is better at producing it than other people. Having an absolute advantage is not the same thing as having a comparative advantage.

Just as Brazil, in our example, is able to benefit from trade with the United States (and vice versa) despite the fact that the United States may be able to produce absolutely more goods than Brazil, in the real-

To learn more, see pages 21–