1.2 10The Circular-Flow Diagram and the National Accounts

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

How economists use aggregate measures to track the performance of the economy

How economists use aggregate measures to track the performance of the economy

How the circular-

How the circular-flow diagram of the economy helps with an understanding of the national accounts

The National Accounts

Almost all countries calculate a set of numbers known as the national income and product accounts. In fact, the accuracy of a country’s accounts is a remarkably reliable indicator of its state of economic development—

National income and product accounts, or national accounts, keep track of spending and the flows of money between different sectors of the economy.

In the United States, these numbers are calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), a division of the U.S. government’s Department of Commerce. The national income and product accounts, often referred to simply as the national accounts, keep track of the spending of consumers, sales of producers, business investment spending, government purchases, and a variety of other flows of money among different sectors of the economy. Let’s see how they work.

The Circular-Flow Diagram

The circular-

To understand the principles behind the national accounts, it helps to look at a graphic called a circular-

The circular-

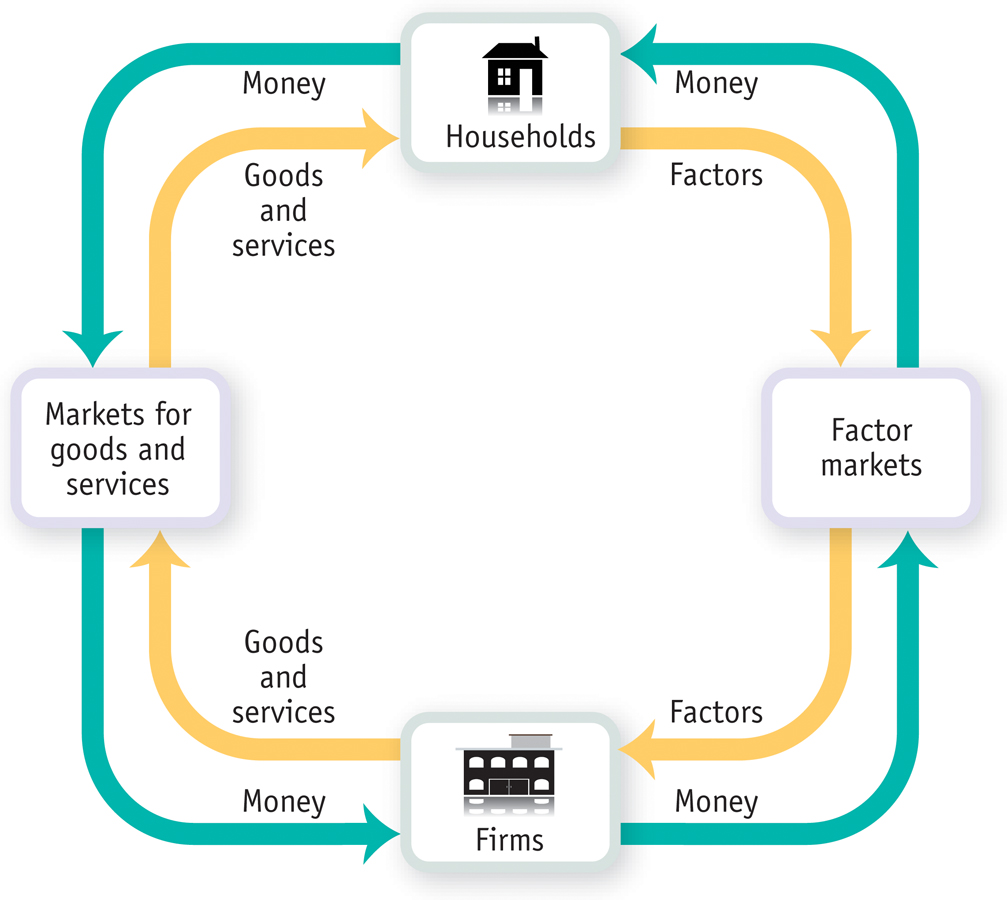

The Simple Circular-Flow Diagram

The U.S. economy is incredibly complex, with more than a hundred million workers employed by millions of companies, producing millions of different goods and services. Yet you can learn some very important things about the economy by considering Figure 10-1. This simple diagram represents the transactions that take place by two kinds of flows around a circle: flows of physical things such as goods, services, labor, or raw materials in one direction, and flows of money that pay for these things in the opposite direction. In this case, the physical flows are shown in yellow, the money flows in green.

A household is a person or group of people who share income.

A firm is an organization that produces goods and services for sale.

The simplest circular-

Product markets are where goods and services are bought and sold.

As you can see in Figure 10-1, there are two kinds of markets in this simple economy. On one side (here the left side) there are markets for goods and services (also known as product markets) in which households buy the goods and services they want from firms. This produces a flow of goods and services to the households and a return flow of money to firms.

Factor markets are where resources, especially capital and labor, are bought and sold.

On the other side (at right) there are factor markets in which firms buy the resources they need to produce goods and services. The best known factor market is the labor market, in which workers are paid for their time. Besides labor, we can think of households as owning and selling the other factors of production to firms.

This simple circular-

The Expanded Circular-Flow Diagram

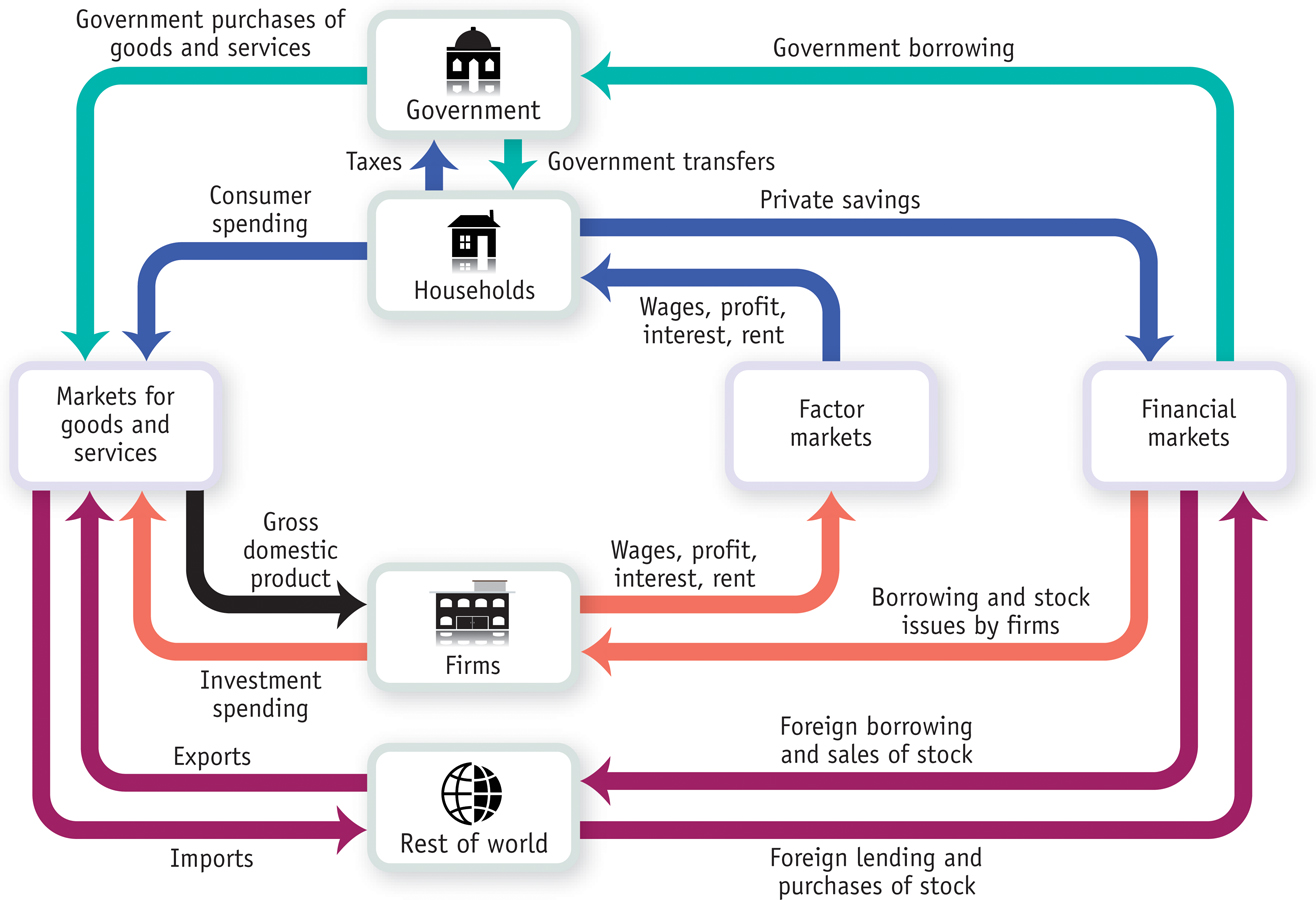

Figure 10-2 is a revised and expanded circular-

- Funds flow from firms to households in the form of wages, profit, interest, and rent through the factor markets. After paying taxes to the government and receiving government transfers, households allocate the remaining income—disposable income—to private savings and consumer spending.

- Via the financial markets, private savings and funds from the rest of the world are channeled into investment spending by firms, government borrowing, foreign borrowing and lending, and foreign transactions of stocks.

- In turn, funds flow from the government and households to firms to pay for purchases of goods and services.

- Finally, exports to the rest of the world generate a flow of funds into the economy and imports lead to a flow of funds out of the economy.

If we add up consumer spending on goods and services, investment spending by firms, government purchases of goods and services, and exports, then subtract the value of imports, the total flow of funds represented by this calculation is total spending on final goods and services produced in the United States. Equivalently, it’s the value of all the final goods and services produced in the United States—

A circular flow of funds connects the four sectors of the economy—

- Funds flow from firms to households in the form of wages, profit, interest, and rent through the factor markets. After paying taxes to the government and receiving government transfers, households allocate the remaining income—

disposable income—to private savings and consumer spending. - Via the financial markets, private savings and funds from the rest of the world are channeled into investment spending by firms, government borrowing, foreign borrowing and lending, and foreign transactions of stocks.

- In turn, funds flow from the government and households to firms to pay for purchases of goods and services.

- Finally, exports to the rest of the world generate a flow of funds into the economy and imports lead to a flow of funds out of the economy.

If we add up consumer spending on goods and services, investment spending by firms, government purchases of goods and services, and exports, then subtract the value of imports, the total flow of funds represented by this calculation is total spending on final goods and services produced in the United States. Equivalently, it’s the value of all the final goods and services produced in the United States—

Consumer spending is household spending on goods and services.

In Figure 10-2, the circular flow of money between households and firms illustrated in Figure 10-1 remains. In the product markets, households engage in consumer spending, buying goods and services from domestic firms and from firms in the rest of the world. Households also own factors of production—

A stock is a share in the ownership of a company held by a shareholder.

A bond is a loan in the form of an IOU that pays interest.

Some households derive additional income from their indirect ownership of the physical capital used by firms, mainly in the form of stocks—shares in the ownership of a company—

Government transfers are payments that the government makes to individuals without expecting a good or service in return.

Disposable income, equal to income plus government transfers minus taxes, is the total amount of household income available to spend on consumption and to save.

Households spend most of the income received from factors of production on goods and services. However, in Figure 10-2 we see two reasons why the markets for goods and services don’t in fact absorb all of a household’s income. First, households don’t get to keep all the income they receive via the factor markets. They must pay part of their income to the government in the form of taxes, such as income taxes and sales taxes. In addition, some households receive government transfers—payments that the government makes to individuals without expecting a good or service in return. Unemployment insurance payments are one example of a government transfer. The total income households have left after paying taxes and receiving government transfers is disposable income.

Private savings, equal to disposable income minus consumer spending, is disposable income that is not spent on consumption.

The banking, stock, and bond markets, which channel private savings and foreign lending into investment spending, government borrowing, and foreign borrowing, are known as the financial markets.

Because the markets for goods and services do not absorb all household income, many households set aside a portion of their income for private savings. These private savings go into financial markets where individuals, banks, and other institutions buy and sell stocks and bonds as well as make loans. As Figure 10-2 shows, the financial markets (on the far right of the circular flow diagram) also receive funds from the rest of the world and provide funds to the government, to firms, and to the rest of the world.

Before going further, we can use the box representing households to illustrate an important general characteristic of the circular-

Government borrowing is the amount of funds borrowed by the government in the financial markets.

Government purchases of goods and services are total expenditures on goods and services by federal, state, and local governments.

Now let’s look at the other inhabitants in the circular-

The rest of the world participates in the U.S. economy in three ways. First, some of the goods and services produced in the United States are sold to residents of other countries. For example, more than half of America’s annual wheat and cotton crops are sold abroad. Goods and services sold to other countries are known as exports. Export sales lead to a flow of funds from the rest of the world into the United States to pay for them.

Second, some of the goods and services purchased by residents of the United States are produced abroad. For example, many consumer goods are now made in China. Goods and services purchased from residents of other countries are known as imports. Import purchases lead to a flow of funds out of the United States to pay for them.

Third, foreigners can participate in U.S. financial markets. Foreign lending—

Inventories are stocks of goods and raw materials held to facilitate business operations.

Investment spending is spending on new productive physical capital, such as machinery and structures, and on changes in inventories.

Note that like households, firms also buy goods and services in our economy. An automobile company that is building a new factory will buy investment goods—

You might ask why changes in inventories are included in investment spending—

It’s also important to understand that investment spending includes spending on the construction of any structure, regardless of whether it is an assembly plant or a new house. Why include the construction of homes? Because, like a plant, a new house produces a future stream of output—

Suppose we add up consumer spending on goods and services, investment spending, government purchases of goods and services, and the value of exports, then subtract the value of imports. This gives us a measure of the overall market value of the goods and services the economy produces. That measure has a name: it’s a country’s gross domestic product, which is the topic of the next module.

CREATING THE NATIONAL ACCOUNTS

The national accounts, like modern macroeconomics, owe their creation to the Great Depression. As the economy plunged into depression, government officials found their ability to respond crippled not only by the lack of adequate economic theories but also by the lack of adequate information. All they had were scattered statistics: railroad freight car loadings, stock prices, and incomplete indexes of industrial production. They could only guess at what was happening to the economy as a whole.

In response to this perceived lack of information, the Department of Commerce commissioned Simon Kuznets, a young Russian-

Kuznets’s initial estimates fell short of the full modern set of accounts because they focused on income, not production. The push to complete the national accounts came during World War II, when policy makers were in need of comprehensive measures of the economy’s performance. The federal government began issuing estimates of gross domestic product and gross national product in 1942.

In January 2000, in the Survey of Current Business, the Department of Commerce ran an article titled “GDP: One of the Great Inventions of the 20th Century.” This may seem a bit over the top, but national income accounting, invented in the United States, has since become a tool of economic analysis and policy making around the world.

10

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

How does a circular-

flow diagram of the economy explain the connection between the following sectors, in terms of the flows that occur between the sectors? -

a. households and firms

Households are linked to firms through the sale of factors of production to firms, through purchases from firms of final goods and services, and through lending funds to firms in the financial markets. -

b. households and government

Households are linked to the government through their payment of taxes, their receipt of transfers, and their lending of funds to the government to finance government borrowing via the financial markets. -

c. households and the rest of the world

Finally, households are linked to the rest of the world through their purchases of imports and transactions with foreigners in financial markets.

-

Define the four different types of income received by households from firms via the factor markets. What is this income used for?

The four types of income received by households are wages, profit, interest, and rent. Wage income is received as payment for selling labor hours to firms. Some of the profit earned by firms is distributed to households who own stock in a company. Interest income is paid to households who hold bonds. In the case of bonds, some households have elected to lend money to firms in return for interest income. Finally, households receive rental income from firms when they rent land or physical structures they own to a firm. Households use their income to pay for consumption spending, taxes, and private savings.

Multiple-

Question

The government uses the _____________ to keep track of the flows of money between different sectors of the economy.

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Markets in which labor and capital are bought and sold are called ___________ markets.

A. B. C. D. E. Question

A circular-

flow diagram assumes the factors of production are owned by A. B. C. D. E. Question

In a circular-

flow diagram, funds that flow between households and the government are A. B. C. D. E. Question

The bank, stock, and money markets are collectively known as the _____________ market.

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

Explain the difference between the market for goods and services, the factor market, and the financial market.