1.4 12Interpreting Real Gross Domestic Product

Andersen Ross/Getty Images

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The difference between real GDP and nominal GDP

The difference between real GDP and nominal GDP

Why real GDP is the appropriate measure of real economic activity

Why real GDP is the appropriate measure of real economic activity

What GDP Tells Us

We now know what gross domestic product (GDP) is and how it’s calculated. But what does the measurement of GDP tell us?

The most important use of GDP is as a measure of the size of the economy, providing us a scale against which to compare the economic performance of other years or other countries. For example, in 2013, U.S. GDP was $16,803 billion, China’s GDP was $9,272 billion, and the combined GDP of the 28 countries that make up the European Union was $17,267 billion. This comparison tells us that China, although it has the world’s second-

Still, one must be careful when using GDP numbers, especially when making comparisons over time. That’s because part of the increase in the value of GDP over time represents increases in the prices of goods and services rather than an increase in output. For example, U.S. GDP was $7,085 billion in 1994 and had approximately doubled to $14,990 billion by 2011. But U.S. production didn’t actually double over that period. To measure actual changes in aggregate output, we need a modified version of GDP that is adjusted for price changes, known as real GDP. We’ll see how real GDP is calculated next.

Real GDP: A Measure of Aggregate Output

In the section-

The moral of this story is that the commonly cited GDP number is an interesting and useful statistic, one that provides a good way to compare the size of different economies, but it’s not a good measure of the economy’s growth over time. GDP can grow because the economy grows, but it can also grow simply because of inflation. Even if an economy’s output doesn’t change, GDP will go up if the prices of the goods and services the economy produces increase. Likewise, GDP can fall either because the economy is producing less or because prices have fallen.

Aggregate output is the total quantity of final goods and services produced within an economy.

To measure the economy’s growth with accuracy, we need a measure of aggregate output: the total quantity of final goods and services the economy produces. The measure that is used for this purpose is known as real GDP. By tracking real GDP over time, we avoid the problem of changes in prices distorting the value of changes in production over time. Let’s look first at how real GDP is calculated and then at what it means.

Calculating Real GDP

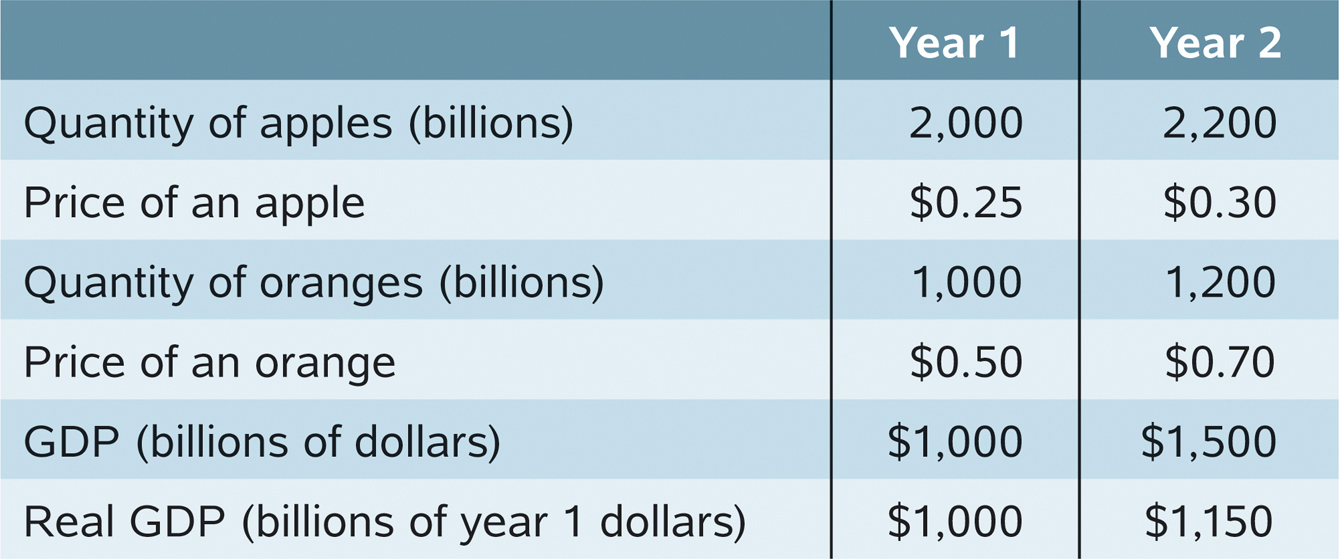

To understand how real GDP is calculated, imagine an economy in which only two goods, apples and oranges, are produced and in which both goods are sold only to final consumers. The outputs and prices of the two fruits for two consecutive years are shown in Table 12-1.

12-1

Calculating GDP and Real GDP in a Simple Economy

The first thing we can say about these data is that the value of sales increased from year 1 to year 2. In the first year, the total value of sales was (2,000 billion × $0.25) + (1,000 billion × $0.50) = $1,000 billion; in the second, it was (2,200 billion × $0.30) + (1,200 billion × $0.70) = $1,500 billion, which is 50% larger. But it is also clear from the table that this increase in the dollar value of GDP overstates the real growth in the economy. Although the quantities of both apples and oranges increased, the prices of both apples and oranges also rose. So part of the 50% increase in the dollar value of GDP simply reflects higher prices, not higher production of output.

To estimate the true increase in aggregate output produced, we have to ask the following question: How much would GDP have gone up if prices had not changed? To answer this question, we need to find the value of output in year 2 expressed in year 1 prices. In year 1, the price of apples was $0.25 each and the price of oranges $0.50 each. So year 2 output at year 1 prices is (2,200 billion × $0.25) + (1,200 billion × $0.50) = $1,150 billion. And output in year 1 at year 1 prices was $1,000 billion. So in this example, GDP measured in year 1 prices rose 15%—from $1,000 billion to $1,150 billion.

Real GDP is the total value of all final goods and services produced in the economy during a given year, calculated using the prices of a selected base year.

Nominal GDP is the total value of all final goods and services produced in the economy during a given year, calculated with the prices current in the year in which the output is produced.

Now we can define real GDP: it is the total value of final goods and services produced in the economy during a year, calculated as if prices had stayed constant at the level of some given base year. A real GDP number always comes with information about what the base year is. A GDP number that has not been adjusted for changes in prices is calculated using the prices in the year in which the output is produced. Economists call this measure nominal GDP, GDP at current prices. If we had used nominal GDP to measure the true change in output from year 1 to year 2 in our apples and oranges example, we would have overstated the true growth in output: we would have claimed it to be 50%, when in fact it was only 15%. By comparing output in the two years using a common set of prices—

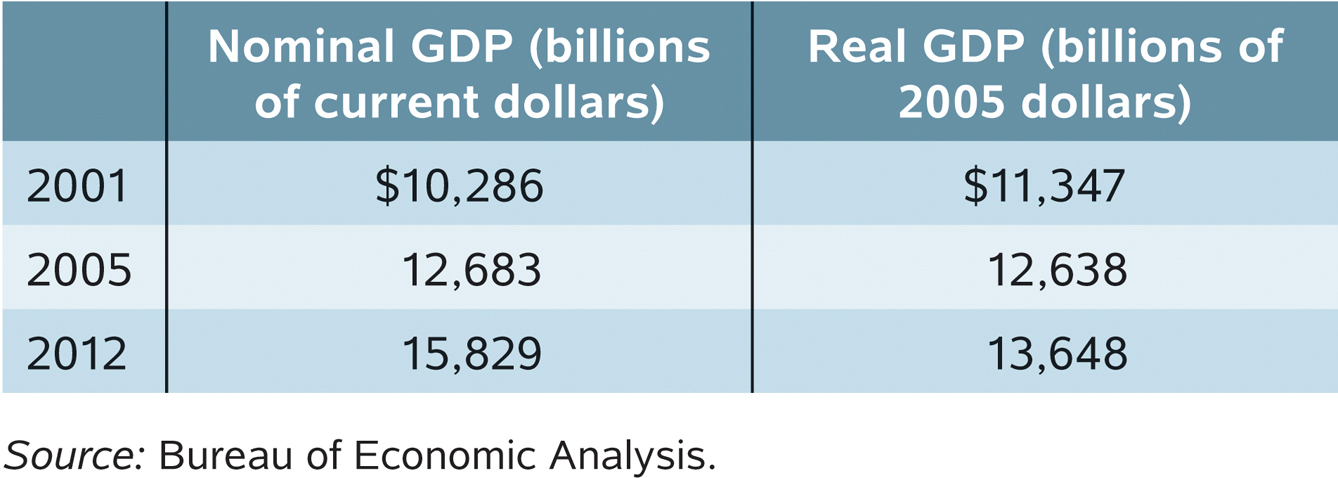

Table 12-2 shows a real-

12-2

Nominal versus Real GDP in 2001, 2005, and 2012

You might have noticed that there is an alternative way to calculate real GDP using the data in Table 12-1. Why not measure it using the prices of year 2 rather than year 1 as the base-

Chained dollars is the method of calculating changes in real GDP using the average between the growth rate calculated using an early base year and the growth rate calculated using a late base year.

In reality, the government economists who put together the U.S. national accounts have adopted a method to measure the change in real GDP known as chain linking, which uses the average between the GDP growth rate calculated using an early base year and the GDP growth rate calculated using a late base year. As a result, U.S. statistics on real GDP are always expressed in chained dollars.

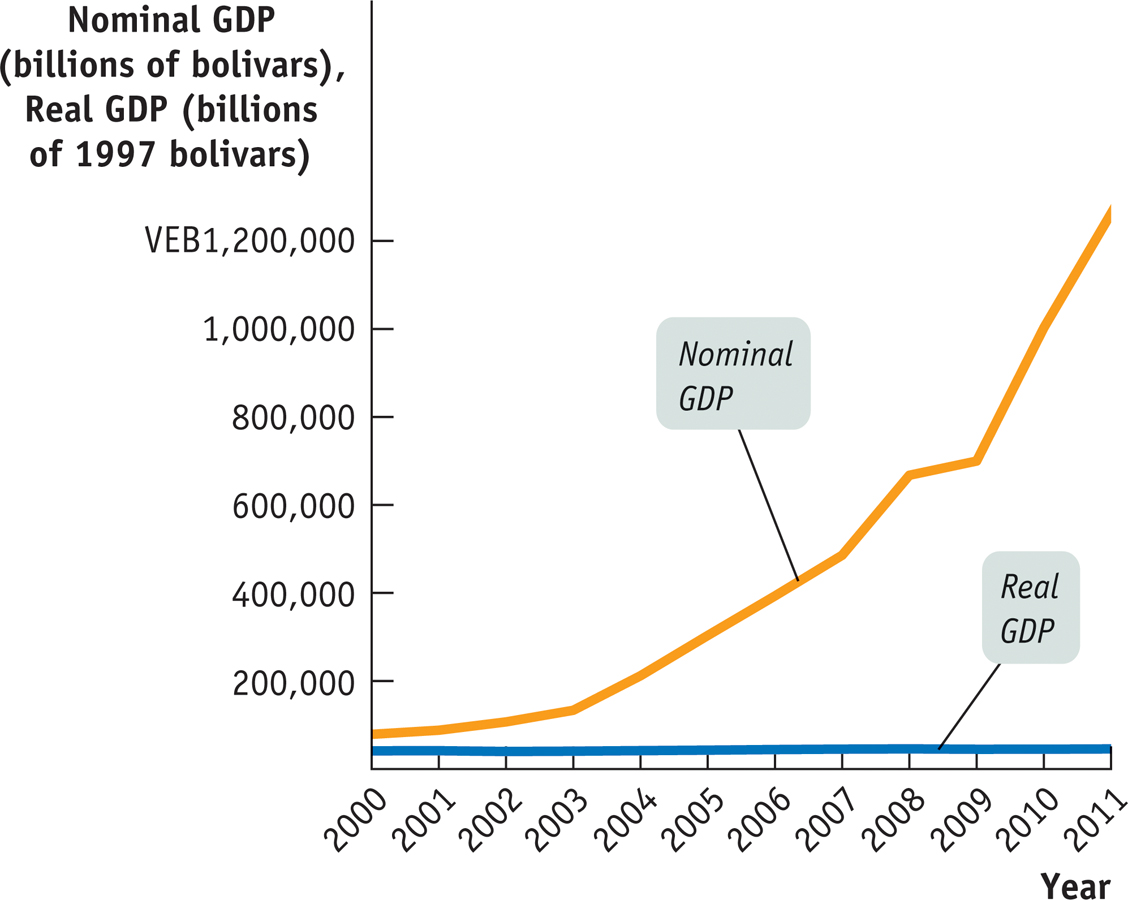

MIRACLE IN VENEZUELA?

The South American nation of Venezuela has a distinction that may surprise you: in recent years, it has had one of the world’s fastest-

So is Venezuela experiencing an economic miracle? No, it’s just suffering from unusually high inflation. Figure 12-1 shows Venezuela’s nominal and real GDP from 2000 to 2011, with real GDP measured in 1997 prices. Real GDP did grow over the period, but at an annual rate of only 3%. That’s about twice the U.S. growth rate over the same period, but it is far short of China’s 10% growth.

What Real GDP Doesn’t Measure

GDP per capita is GDP divided by the size of the population; it is equivalent to the average GDP per person.

Real GDP per capita is the average real GDP per person.

GDP is a measure of a country’s aggregate output. Other things equal, a country with a larger population will have higher GDP simply because there are more people working. So if we want to compare GDP across countries but want to eliminate the effect of differences in population size, we use the measure GDP per capita—GDP divided by the size of the population, equivalent to the average GDP per person. Correspondingly, real GDP per capita is the average real GDP per person.

Real GDP per capita can be a useful measure in some circumstances, such as in a comparison of labor productivity between two countries. However, despite the fact that it is a rough measure of the average real output per person, real GDP per capita has well-

Every once in a while economists are accused of believing that growth in real GDP per capita is the only thing that matters—

Real GDP does not include many of the things that contribute to happiness, such as leisure time, volunteerism, housework, and natural beauty. And real GDP increases with expenditures on some things that make people unhappy, including disease, divorce, crime, and natural disasters.

Real GDP per capita is a measure of an economy’s average aggregate output per person—

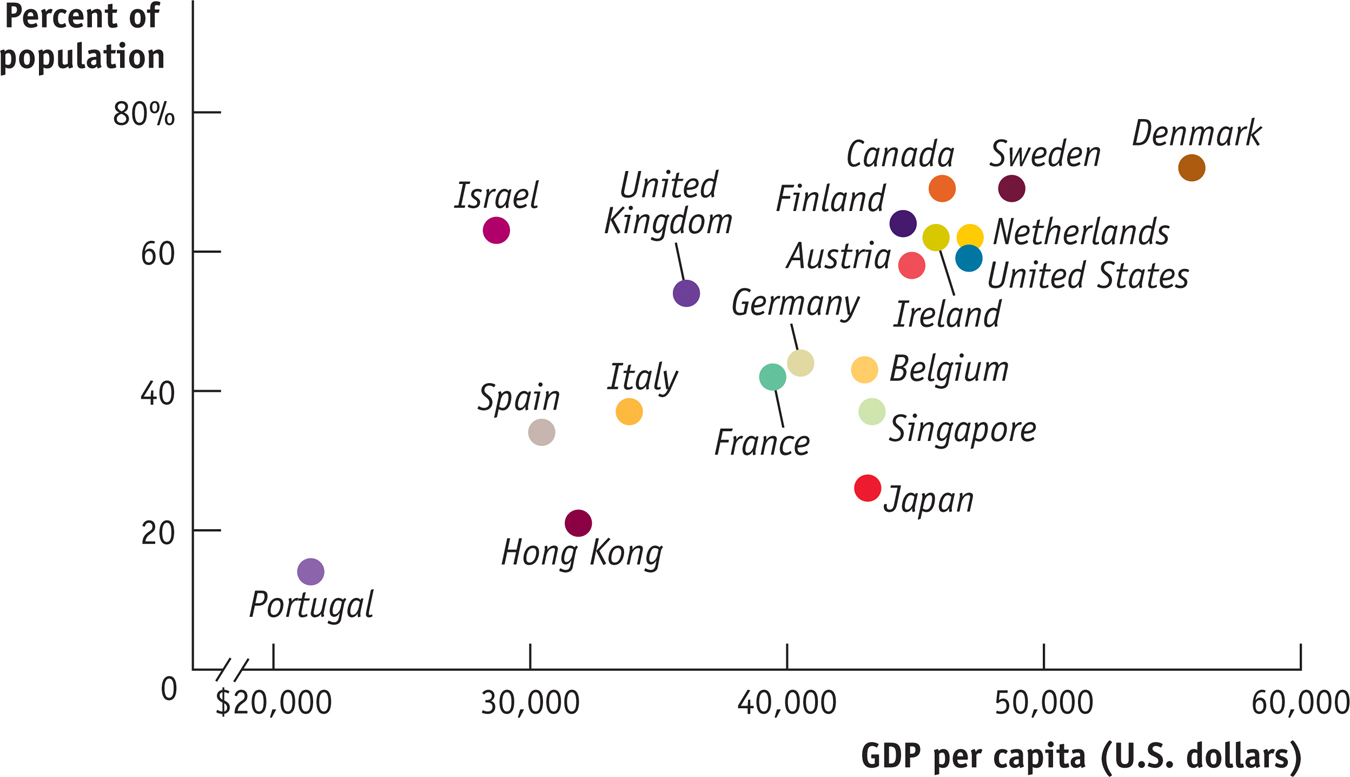

GDP AND THE MEANING OF LIFE

“I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor,” the actress Mae West famously declared. “Believe me, rich is better.” But is the same true for countries?

This figure shows two pieces of information for a number of countries: how rich they are, as measured by GDP per capita, and how people assess their well-

- Rich is better. Richer countries on average have higher well-

being than poor countries. - Money matters less as you grow richer. The gain in life satisfaction as you go from GDP per capita of $20,000 to $30,000 is greater than the gain as you go from $40,000 to $50,000.

- Money isn’t everything. Israelis, though rich by world standards, are poorer than Americans—

but they seem more satisfied with their lives. Japan is richer than most other nations, but by and large, quite miserable.

These results are consistent with the observation that high GDP per capita makes it easier to achieve a good life but that countries aren’t equally successful in taking advantage of that possibility.

12

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

Assume there are only two goods in the economy, french fries and onion rings. In 2012, 1,000,000 servings of french fries were sold for $0.40 each and 800,000 servings of onion rings were sold for $0.60 each. From 2012 to 2013, the price of french fries rose to $0.50 and the servings sold fell to 900,000; the price of onion rings fell to $0.51 and the servings sold rose to 840,000.

-

a. Calculate nominal GDP in 2012 and 2013. Calculate real GDP in 2013 using 2012 prices.

In 2012 nominal GDP was (1,000,000 × $0.40) + (800,000 × $0.60) = $400,000 + $480,000 = $880,000. The total value of sales of french fries in 2013 was 900,000 × $0.50 = $450,000. The total value of sales of onion rings in 2013 was 840,000 × $0.51 = $428,400. Nominal GDP in 2013 was $450,000 + $428,400 = $878,400. To find real GDP in 2013, we must calculate the value of sales in 2013 using 2012 prices: (900,000 × $0.40) + (840,000 × $0.60) = $360,000 + $504,000 = $864,000. -

b. Why would an assessment of growth using nominal GDP be misguided?

A comparison of nominal GDP in 2012 to nominal GDP in 2013 shows a decline of (($880,000 − $878,400)/$880,000) × 100 = 0.18%. But a comparison using real GDP shows a decline of (($880,000 − $864,000)/$880,000) × 100 = 1.8%. That is, a calculation based on real GDP shows a drop 10 times larger (1.8%) than a calculation based on nominal GDP (0.18%): in this case, the calculation based on nominal GDP underestimates the true magnitude of the change because it incorporates both quantity changes and price changes.

-

From 1990 to 2000 the price of housing rose dramatically. What are the implications of this in deciding whether to use 1990 or 2000 as the base year in calculating 2010 real GDP?

A price index based on 1990 prices will contain a relatively low price of housing compared to a price index based on 2000 prices. This means that a 2000 price index used to calculate real GDP in 2010 will magnify the value of housing production in the economy and increase the relative size of the housing sector as a component of real GDP.

Multiple-

Question

Which of the following is true of real GDP?

I. It is adjusted for changes in prices.

II. It is always equal to nominal GDP.

III. It increases whenever aggregate output increases.A. B. C. D. E. Question

The best measure for comparing a country’s aggregate output over time is

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Use the information provided in the table below for an economy that produces only apples and oranges. Assume year 1 is the base year. What was the value of real GDP in each year?

Year 1Year 2

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Real GDP per capita is an imperfect measure of the quality of life in part because it

A. B. C. D. E. Question

Refer to the 2011 data in the following table. Which of the following must be true?

I. Residents of China were worse off than residents of the United States or the European Union.

II. The European Union had a higher nominal GDP per capita than the United States.

III. The European Union had a larger economy than the United States.

A. B. C. D. E.

Critical-

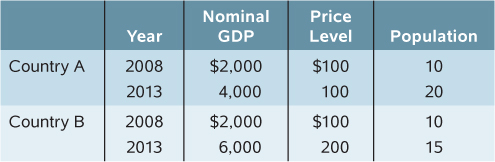

Use the information in the accompanying table to answer the following questions.

Calculate the percent increase in nominal GDP between 2008 and 2013 for each country.

Country A: (4,000–2,000/2,000) × 100 = 100%

Country B: (6,000–2,000/2,000) × 100 = 200%What happened to the price level in each country between 2008 and 2013?

Country A: It stayed the same.

Country B: It doubled.Calculate real GDP in each country in 2013, using 2008 as the base year.

Country A: $4,000 (There was no price increase so it is the same.)

Country B: $6,000/2 = $3,000 (Prices doubled.)Calculate the percent increase in real GDP between 2008 and 2013 for each country.

Country A: (4,000–2,000/2,000) × 100 = 100%

Country B: (3,000–2,000/2,000) × 100 = 50%Compare the two countries’ real GDP per capita in 2013 using 2008 as the base year.

Country A: 4,000/20 = $200 versus

Country B: 3,000/15 = $200. It is the same.