17: Crises and Consequences

!arrow! What You Will Learn in This Section

How depository banks and shadow banks differ

Why, despite their differences, both types of banks are subject to bank runs

What happens during financial panics and banking crises

Why the effects of panics and crises on the economy are so severe and long-

lasting How regulatory loopholes and the rise of shadow banking led to the financial crisis of 2008

How a new regulatory framework seeks to avoid another crisis

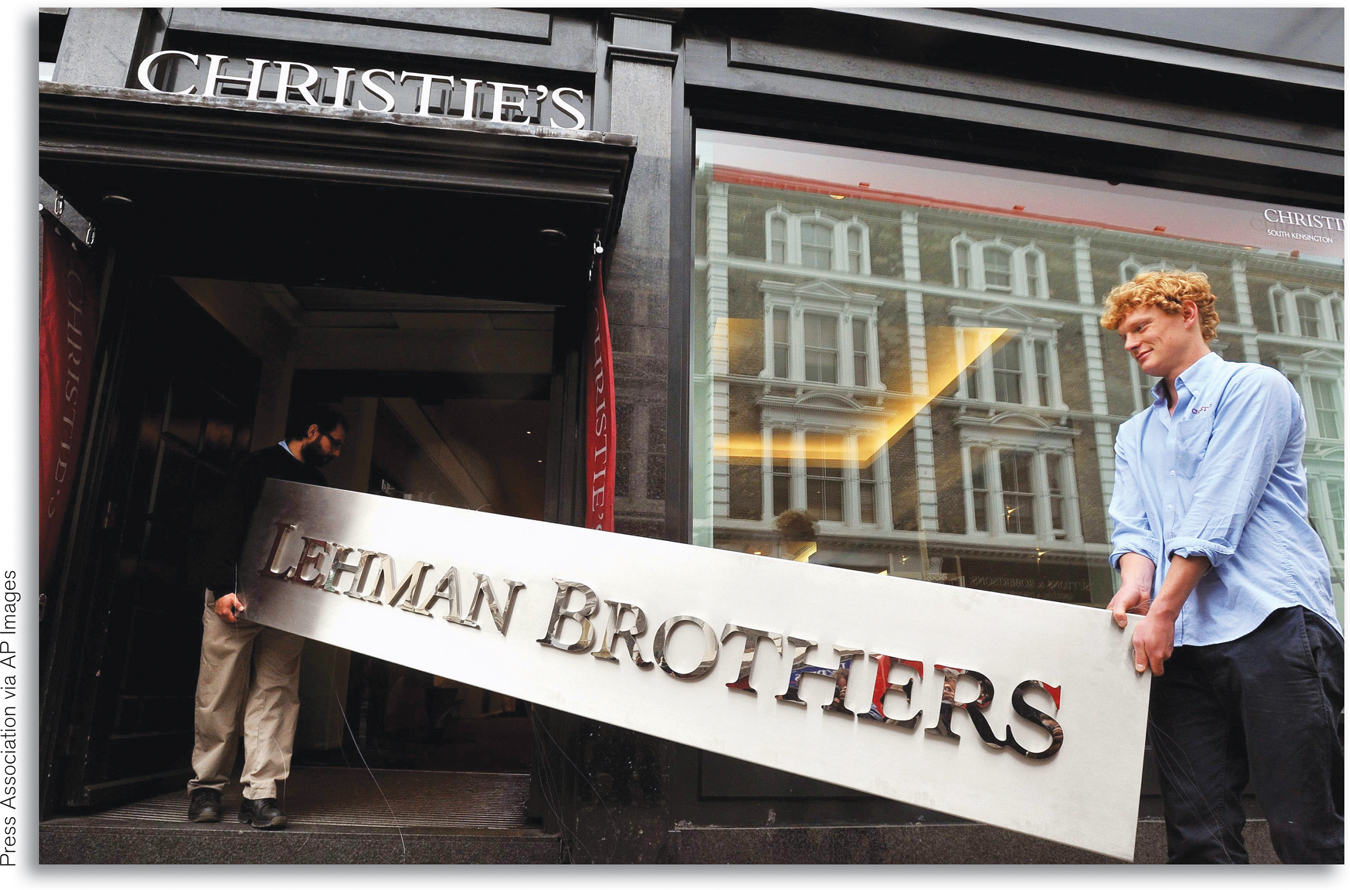

FROM PURVEYOR OF DRY GOODS TO DESTROYER OF WORLDS

In 1844 Henry Lehman, a German immigrant, opened a dry goods store in Montgomery, Alabama. Over time, Lehman and his brothers, who followed him to America, branched out into cotton trading, then into a variety of financial activities. By 1850, Lehman Brothers was established on Wall Street; by 2008, thanks to its skill at trading financial assets, Lehman Brothers was one of the nation’s top investment banks. Unlike commercial banks, investment banks trade in financial assets and don’t accept deposits from customers.

But in September 2008, Lehman’s luck ran out. The firm had invested heavily in subprime mortgages—

Lehman had been borrowing heavily in the short-

When Lehman fell, it set off a chain of events that came close to taking down the entire world financial system. Because Lehman had hidden the severity of its vulnerability, its failure came as a nasty surprise. Through securitization (a concept we defined in Section 14), financial institutions throughout the world were exposed to real estate loans that were quickly deteriorating in value as default rates on those loans rose. Credit markets froze because those with funds to lend decided it was better to sit on the funds rather than lend them out and risk losing them to a borrower who might go under like Lehman had. Around the world, borrowers were hit by a global credit crunch: they either lost their access to credit or found themselves forced to pay drastically higher interest rates. Stocks plunged, and within weeks the Dow had fallen almost 3,000 points, more than a quarter of its value.

Nor were the consequences limited to financial markets. The U.S. economy was already in recession when Lehman fell, but the pace of the downturn accelerated drastically in the months that followed, resulting in the Great Recession, the worst slump in the U.S. economy since the Great Depression of the 1930s. By the time U.S. employment bottomed out in early 2010, more than 8 million jobs had been lost. Europe and Japan were also suffering their worst recessions since the 1930s, and world trade plunged even faster than it had in the first year of the Great Depression.

All of this came as a great shock because few people imagined that such events were possible in twenty-

On reflection, the panic following Lehman’s collapse was not unique, even in the modern world. The failure of Long-

Financial panics and banking crises have happened fairly often, sometimes with disastrous effects on output and employment. Chile’s 1981 banking crisis was followed by a 19% decline in real GDP per capita and a slump that lasted through most of the following decade. Finland’s 1990 banking crisis was followed by a surge in the unemployment rate from 3.2% to 16.3%. Japan’s banking crisis of the early 1990s led to more than a decade of economic stagnation.

In this section, we’ll examine the causes and consequences of banking crises and financial panics, expanding on the discussion of this topic in Section 14. We’ll begin by examining what makes banking vulnerable to a crisis and how this can mutate into a full-