Banking Crises, Recessions, and Recovery

A severe banking crisis is one in which a large fraction of the banking system either fails outright (that is, goes bankrupt) or suffers a major loss of confidence and must be bailed out by the government. Such crises almost invariably lead to deep recessions, which are usually followed by slow recoveries.

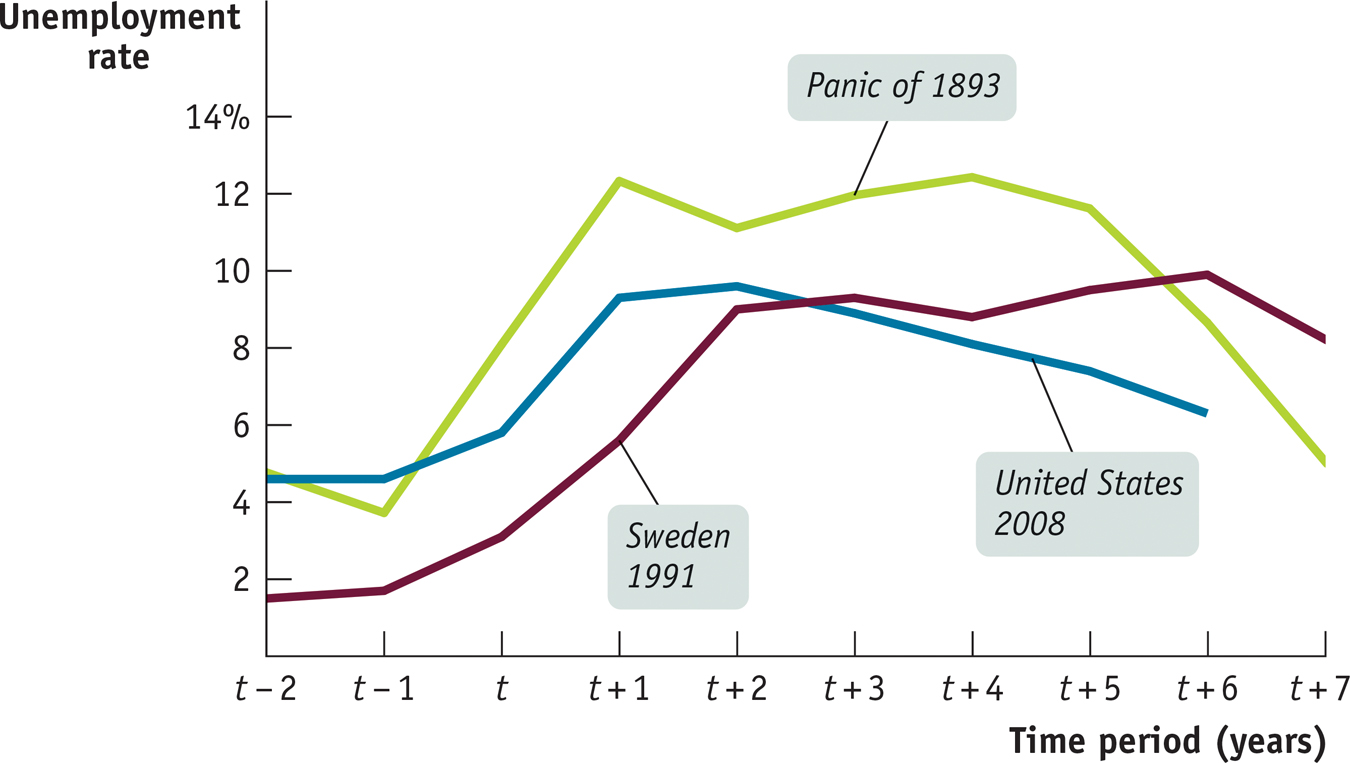

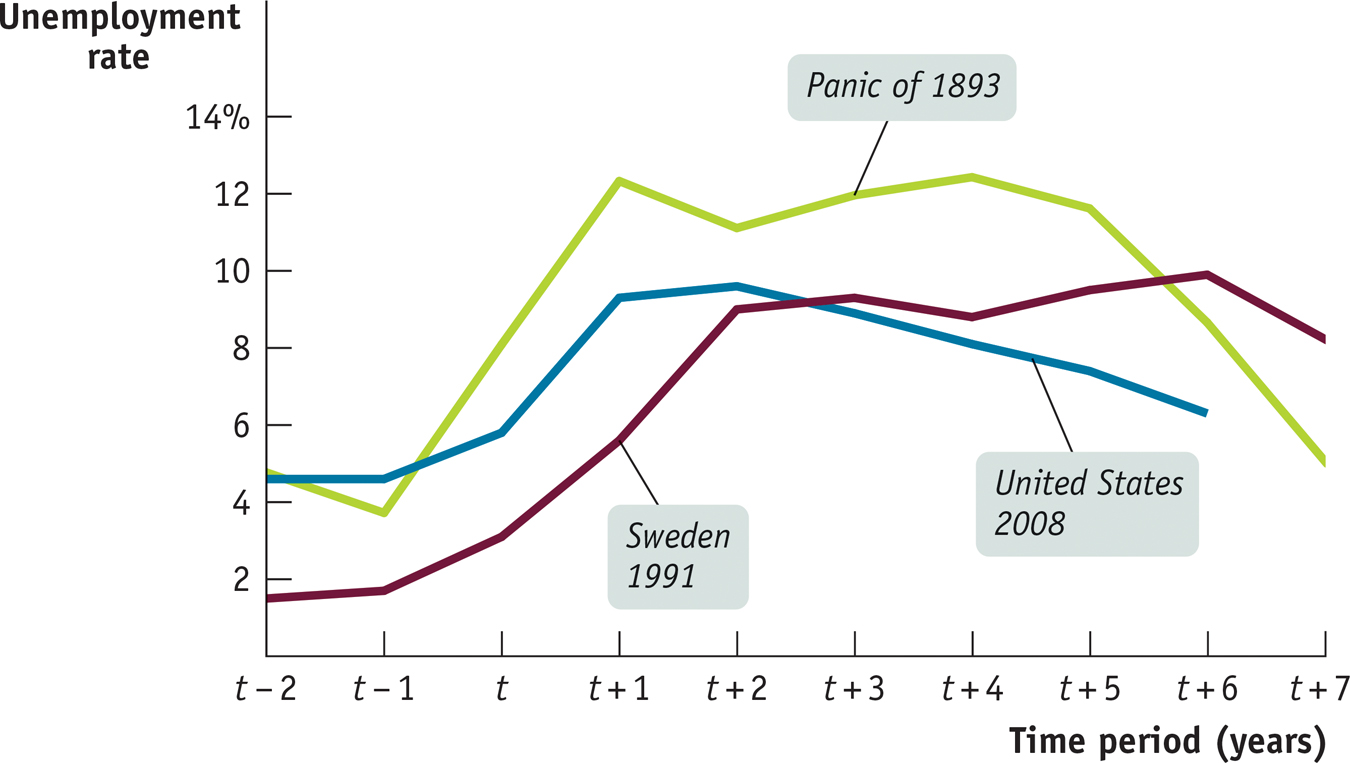

Figure 17-2 illustrates this phenomenon by tracking unemployment in the aftermath of three banking crises widely separated in space and time: the Panic of 1893, the Swedish banking crisis of 1991, and the American financial crisis of 2008 that spawned the Great Recession. In the figure, t represents the year of the crisis: 1893 for the United States, 1991 for Sweden. As the figure shows, these three crises, spanning over 100 years and continents apart, produced similarly devastating results: unemployment shot up and came down only slowly and erratically so that the number of jobless remained high by pre-crisis standards for many years. A third line shows U.S. unemployment in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis.

Unemployment Rates, Before and After Banking Crises This figure tracks unemployment in the wake of three banking crises: the Panic of 1893, the Swedish banking crisis of 1991, and the American financial crisis of 2008. t represents the year of the crisis—1893 for the Panic of 1893, 1991 for the Swedish banking crisis, and 2008 for the American financial crisis of that year. t − 2 is the date two years before the crisis hit; t + 5 is the date five years after. In all three cases, the economy suffered severe damage from the banking crisis: unemployment shot up and came down only slowly and erratically. In all three cases, five years after the crisis the unemployment rate remained high compared to pre-crisis levels. Sources: Christina D. Romer, “Spurious Volatility in Historical Unemployment Data,” Journal of Political Economy 94, no. 1 (1986): 1–37; Eurostat; Bureau of Labor Statistics.

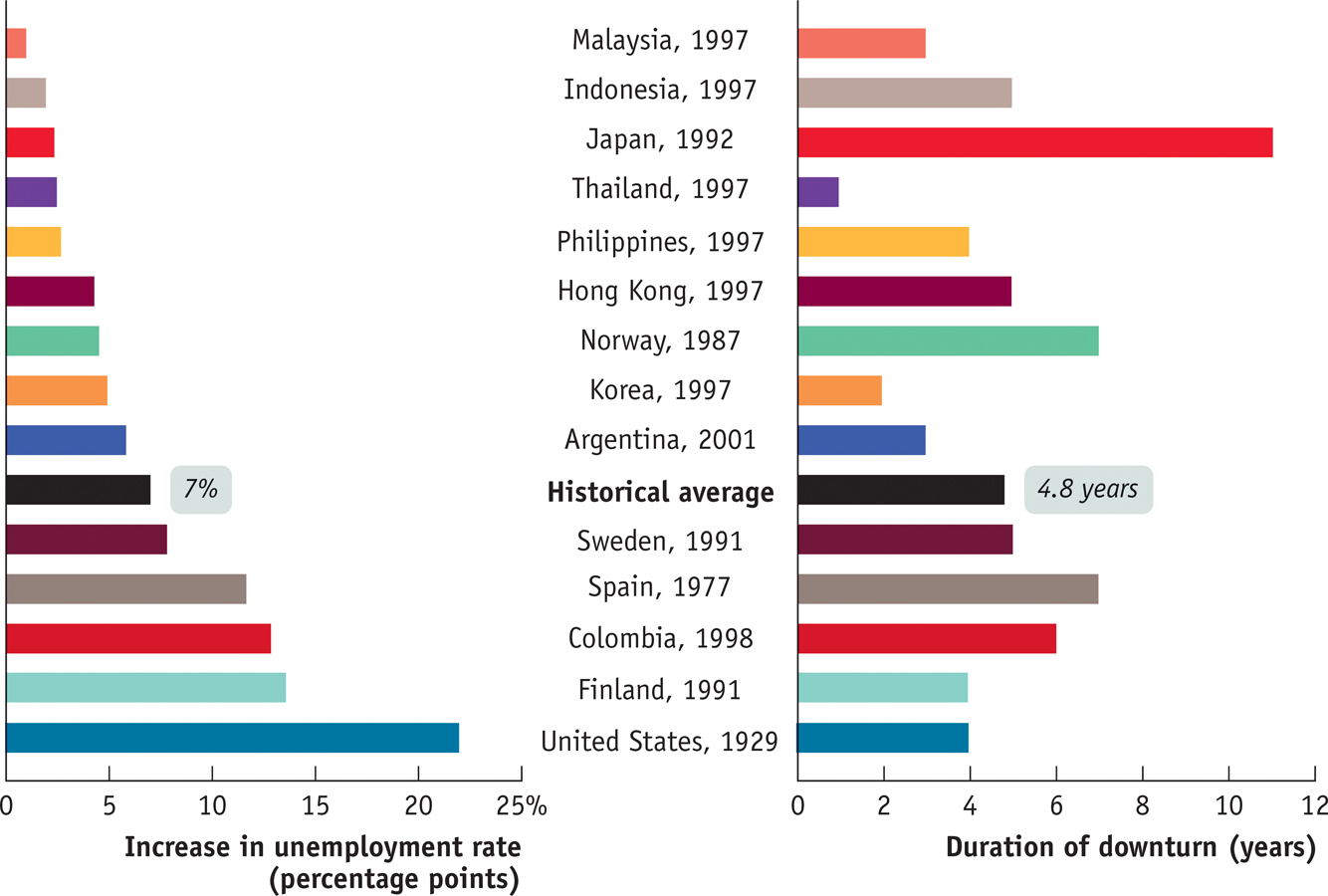

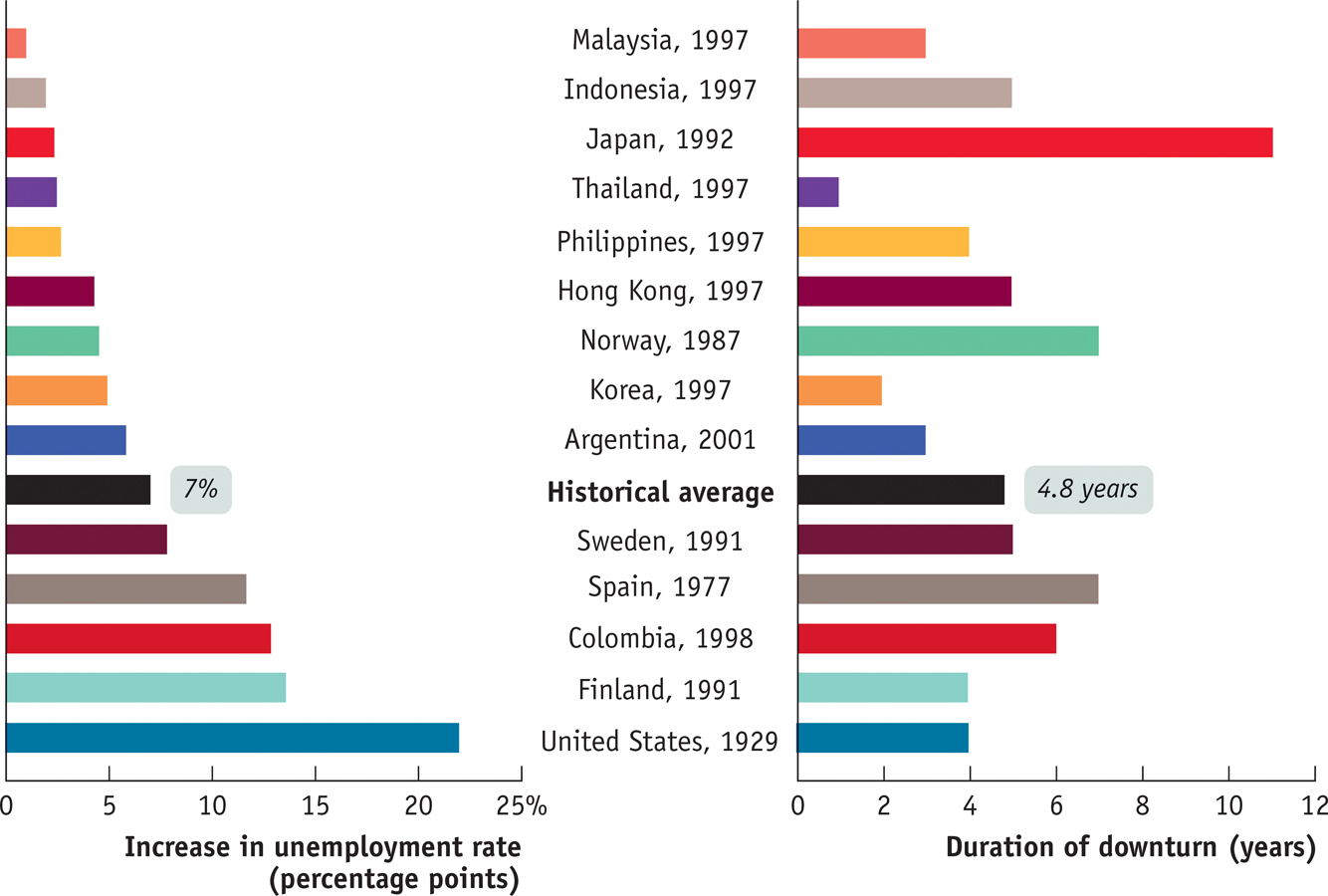

These historical examples are typical. Figure 17-3, taken from a widely cited study by the economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, compares employment performance in the wake of a number of severe banking crises. The bars on the left show the rise in the unemployment rate during and following the crisis; the bars on the right show the time it took before unemployment began to fall. The numbers are shocking: on average, severe banking crises have been followed by a 7-percentage-point rise in the unemployment rate, and in many cases it has taken four years or more before the unemployment rate even begins to fall, let alone returns to pre-crisis levels.

Episodes of Banking Crises and Unemployment Economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff have compared employment performance across several countries in the aftermath of a number of severe banking crises. For each country, the bar on the left shows the rise in the unemployment rate during and following the crisis, and the bar on the right shows how long it took for unemployment to begin to fall. On average, severe banking crises have been followed by a 7-percentage-point rise in the unemployment rate, and in many cases it has taken four years or more before unemployment even begins to fall, let alone returns to pre-crisis levels. Source: Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff, “The Aftermath of Financial Crises,” American Economic Review 99, no. 2 (2009): 466–472.