The Multiplier Process and Inventory Adjustment

We’ve just learned about a very important feature of the macroeconomy: when planned spending by households and firms does not equal the current aggregate output by firms, this difference shows up in changes in inventories. The response of firms to those inventory changes moves real GDP over time to the point at which real GDP and planned aggregate spending are equal. That’s why, as we mentioned earlier, changes in inventories are considered a leading indicator of future economic activity.

Now that we understand how real GDP moves to achieve income–

In our simple model there are only two possible sources of a shift of the planned aggregate spending line: a change in planned investment spending, IPlanned, or a shift of the aggregate consumption function, CF. For example, a change in IPlanned can occur because of a change in the interest rate. (Remember, we’re assuming that the interest rate is fixed by factors that are outside the model. But we can still ask what happens when the interest rate changes.) A shift of the aggregate consumption function (that is, a change in its vertical intercept, A) can occur because of a change in aggregate wealth—

Recall from earlier in this chapter that an autonomous change in planned aggregate spending is a change in the desired level of spending by firms, households, and government at any given level of real GDP (although we’ve assumed away the government for the time being). How does an autonomous change in planned aggregate spending affect real GDP in income–

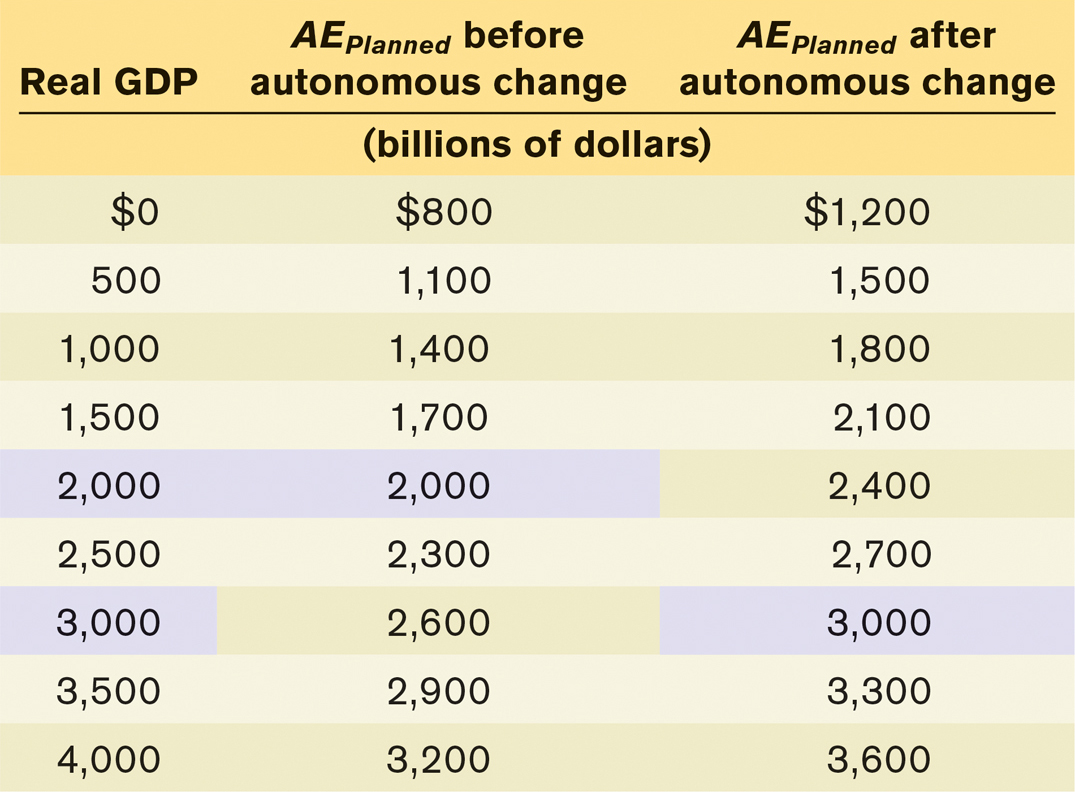

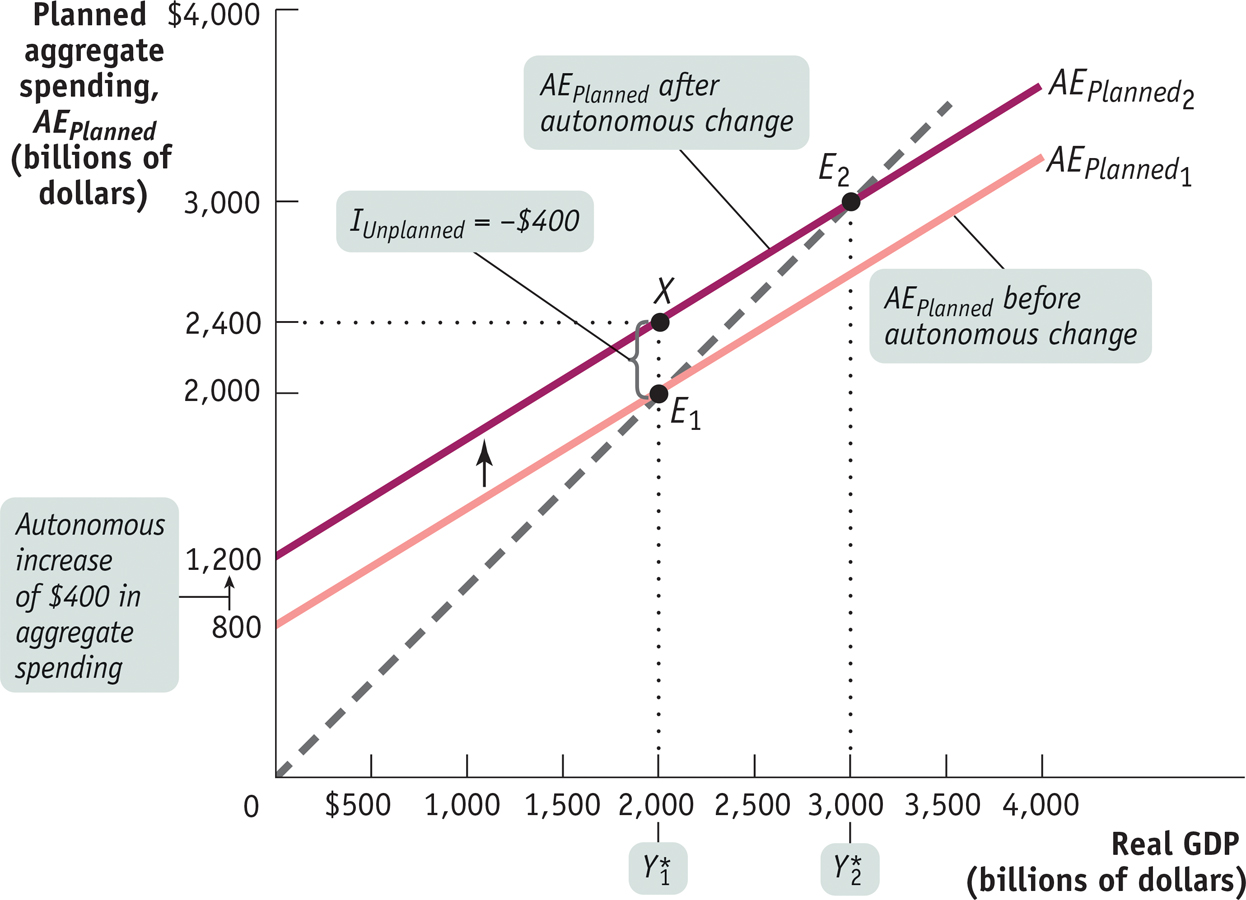

Table 11-4 and Figure 11-11 start from the same numerical example we used in Table 11-3 and Figure 11-10. They also show the effect of an autonomous increase in planned aggregate spending of 400— is 2,000. The autonomous rise in planned aggregate spending shifts the planned aggregate spending line up, leading to a new income–

is 2,000. The autonomous rise in planned aggregate spending shifts the planned aggregate spending line up, leading to a new income– is 3,000.

is 3,000.

, equal to 2,000. An autonomous increase in AEPlanned of 400 shifts the planned aggregate spending line upward by 400. The economy is no longer in income–

, equal to 2,000. An autonomous increase in AEPlanned of 400 shifts the planned aggregate spending line upward by 400. The economy is no longer in income– , equal to 3,000.

, equal to 3,000.The fact that the rise in income–

We can examine in detail what underlies the multistage multiplier process by looking more closely at Figure 11-11. First, starting from E1, the autonomous increase in planned aggregate spending leads to a gap between planned aggregate spending and real GDP. This is represented by the vertical distance between X, at 2,400, and E1, at 2,000. This gap illustrates an unplanned fall in inventory investment: IUnplanned = − 400. Firms respond by increasing production, leading to a rise in real GDP from  . The rise in real GDP translates into an increase in disposable income, YD. That’s the first stage in the chain reaction. But it doesn’t stop there—

. The rise in real GDP translates into an increase in disposable income, YD. That’s the first stage in the chain reaction. But it doesn’t stop there—

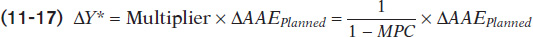

We can summarize these results in an equation, where ΔAAEPlanned represents the autonomous change in AEPlanned, and  , the subsequent change in income–

, the subsequent change in income–

Recalling that the multiplier, 1/(1 − MPC), is greater than 1, Equation 11- .

.

The Paradox of Thrift You may recall that in Chapter 6 we mentioned the paradox of thrift to illustrate the fact that in macroeconomics the outcome of many individual actions can generate a result that is different from and worse than the simple sum of those individual actions. In the paradox of thrift, households and firms cut their spending in anticipation of future tough economic times. These actions depress the economy, leaving households and firms worse off than if they hadn’t acted virtuously to prepare for tough times. It is called a paradox because what’s usually “good” (saving to provide for your family in hard times) is “bad” (because it can make everyone worse off).

Using the multiplier, we can now see exactly how this scenario unfolds. Suppose that there is a slump in consumer spending or investment spending, or both, just like the slump in residential construction investment spending leading up to the 2007–

Conversely, prodigal behavior is rewarded: if consumers or producers increase their spending, the resulting multiplier process makes the increase in income–

It’s important to realize that our result that the multiplier is equal to 1/(1 − MPC) depends on the simplifying assumption that there are no taxes or transfers, so that disposable income is equal to real GDP. In the appendix to Chapter 13, we’ll bring taxes into the picture, which makes the expression for the multiplier more complicated and the multiplier itself smaller. But the general principle we have just learned—

As we noted earlier in this chapter, declines in planned investment spending are usually the major factor causing recessions, because historically they have been the most common source of autonomous reductions in aggregate spending. The tendency of the consumption function to shift upward over time, which we pointed out earlier in the Economics in Action, “Famous First Forecasting Failures,” means that autonomous changes in both planned investment spending and consumer spending play important roles in expansions. But regardless of the source, there are multiplier effects in the economy that magnify the size of the initial change in aggregate spending.

ECONOMICS in Action: Inventories and the End of a Recession

Inventories and the End of a Recession

Avery clear example of the role of inventories in the multiplier process took place in late 2001, as that year’s recession came to an end. The driving force behind the recession was a slump in business investment spending. It took several years before investment spending bounced back in the form of a housing boom. Still, the economy did start to recover in late 2001, largely because of an increase in consumer spending—

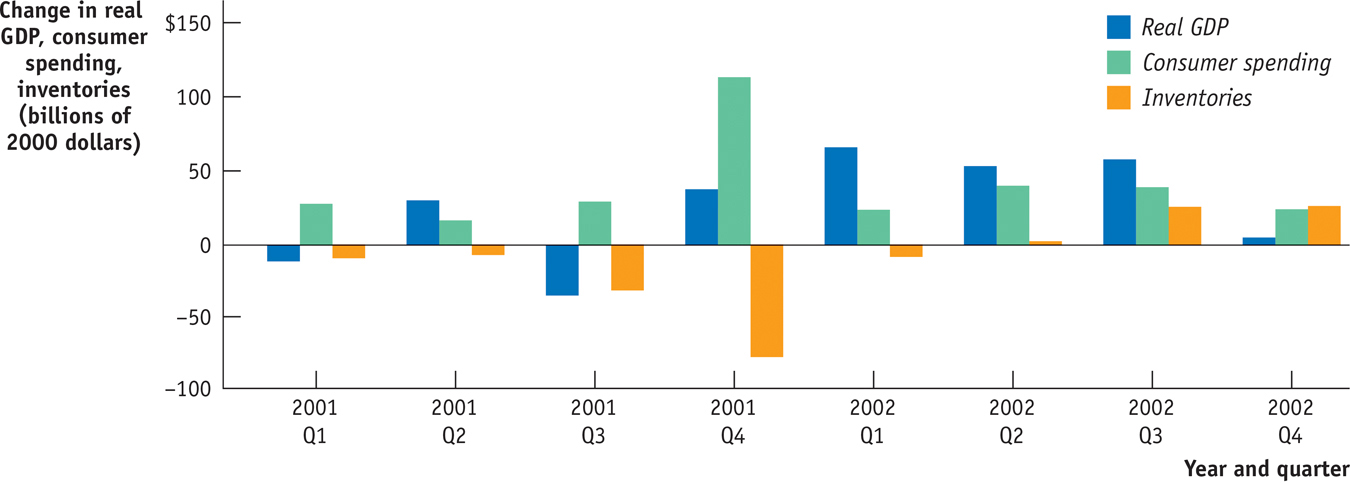

Initially, this increase in consumer spending caught manufacturers by surprise. Figure 11-12 shows changes in real GDP, real consumer spending, and real inventories in each quarter of 2001 and 2002. Notice the surge in consumer spending in the fourth quarter of 2001. It didn’t lead to a lot of GDP growth because it was offset by a plunge in inventories. But in the first quarter of 2002 producers greatly increased their production, leading to a jump in real GDP.

Quick Review

The economy is in income–

expenditure equilibrium when planned aggregate spending is equal to real GDP. At any output level greater than income–

expenditure equilibrium GDP, real GDP exceeds planned aggregate spending and inventories are rising. At any lower output level, real GDP falls short of planned aggregate spending and inventories are falling. After an autonomous change in planned aggregate spending, the economy moves to a new income–

expenditure equilibrium through the inventory adjustment process, as illustrated by the Keynesian cross. Because of the multiplier effect, the change in income– expenditure equilibrium GDP is a multiple of the autonomous change in aggregate spending.

11-4

Question 11.9

Although economists believe that recessions typically begin as slumps in investment spending, they also believe that consumer spending eventually slumps during a recession. Explain why.

Question 11.10

Use a diagram like Figure 11-10 to show what happens when there is an autonomous fall in planned aggregate spending. Describe how the economy adjusts to a new income–

expenditure equilibrium. Suppose Y* is originally $500 billion, the autonomous reduction in planned aggregate spending is $300 million ($0.3 billion), and MPC = 0.5. Calculate Y* after such a change.

Solutions appear at back of book.

What’s Good for America Is Good for GM

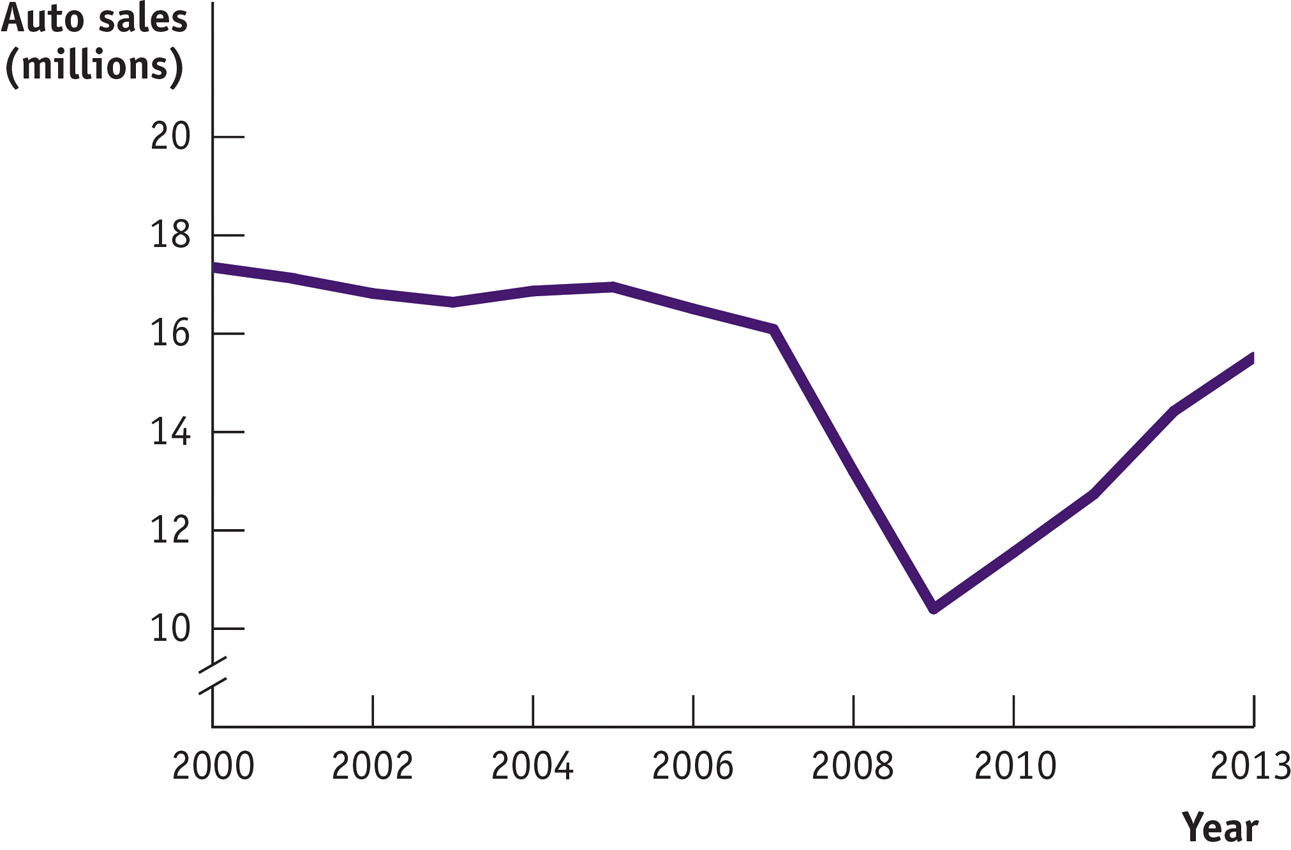

In 2009, with the economy in a steep nose-

General Motors—

By 2009 the fate of GM and the fate of America seemed less intertwined. Still, the case for the bailout rested crucially on the belief that GM’s problems weren’t entirely self-

On the face of it, this interdependence wasn’t entirely obvious: the 2007–

Did saving GM justify the bailout? The company’s recovery meant that taxpayers got most of their money back—

Defenders of the bailout nonetheless declared it a success, because it resuscitated the U.S. auto industry and saved many jobs, not just in the auto companies and their suppliers, but in the many businesses whose sales depend on the incomes of workers employed in the auto industry. In the summer of 2009 the unemployment rate in Michigan, still America’s automotive heartland, rose above 14%—but it then began a rapid decline, falling to 7.4% by early 2014. Few would argue that the speedy recovery in employment in Michigan would have happened without the auto bailout.

In the end, GM bounced back because the U.S. economy as a whole recovered; what was good for America was indeed still good for General Motors. And what was good for General Motors was clearly good for Michigan—

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 11.11

Why did a national slump that began with housing affect companies like General Motors?

Question 11.12

Why was it reasonable in June 2009 to predict that auto sales would improve in the near future?

Question 11.13

How does this story about General Motors help explain how a slump in housing—