The Zero Lower Bound Problem

As Figure 15-9 shows, a Taylor rule based on inflation and the unemployment rate does a good job of predicting Federal Reserve policy from 1988 through 2008. After that, however, things go awry, and for a simple reason: with very high unemployment and low inflation, the same Taylor rule called for an interest rate less than zero, which isn’t possible.

Why aren’t negative interest rates possible? Because people always have the alternative of holding cash, which offers a zero interest rate. Nobody would ever buy a bond yielding an interest rate less than zero because holding cash would be a better alternative.

The zero lower bound for interest rates means that interest rates cannot fall below zero.

The fact that interest rates can’t go below zero—

In November 2010 the Fed began an attempt to circumvent this problem, which went by the somewhat obscure name “quantitative easing.” Instead of purchasing only short-

Later the Fed expanded the program further, also purchasing mortgage-

Was this policy effective? The Federal Reserve believes that it helped the economy. However, the pace of recovery remained disappointingly slow.

ECONOMICS in Action: What the FED Wants, the FED Gets

What the FED Wants, the FED Gets

What’s the evidence that the Fed can actually cause an economic contraction or expansion? You might think that finding such evidence is just a matter of looking at what happens to the economy when interest rates go up or down. But it turns out that there’s a big problem with that approach: the Fed usually changes interest rates in an attempt to tame the business cycle, raising rates if the economy is expanding and reducing rates if the economy is slumping. So in the actual data, it often looks as if low interest rates go along with a weak economy and high rates go along with a strong economy.

In a famous 1994 paper titled “Monetary Policy Matters,” the macroeconomists Christina Romer and David Romer solved this problem by focusing on episodes in which monetary policy wasn’t a reaction to the business cycle. Specifically, they used minutes from the Federal Open Market Committee and other sources to identify episodes “in which the Federal Reserve in effect decided to attempt to create a recession to reduce inflation.” As we’ll learn in the next chapter, rather than just using monetary policy as a tool of macroeconomic stabilization, sometimes it is used to eliminate embedded inflation—inflation that people believe will persist into the future. In such a case, the Fed needs to create a recessionary gap—

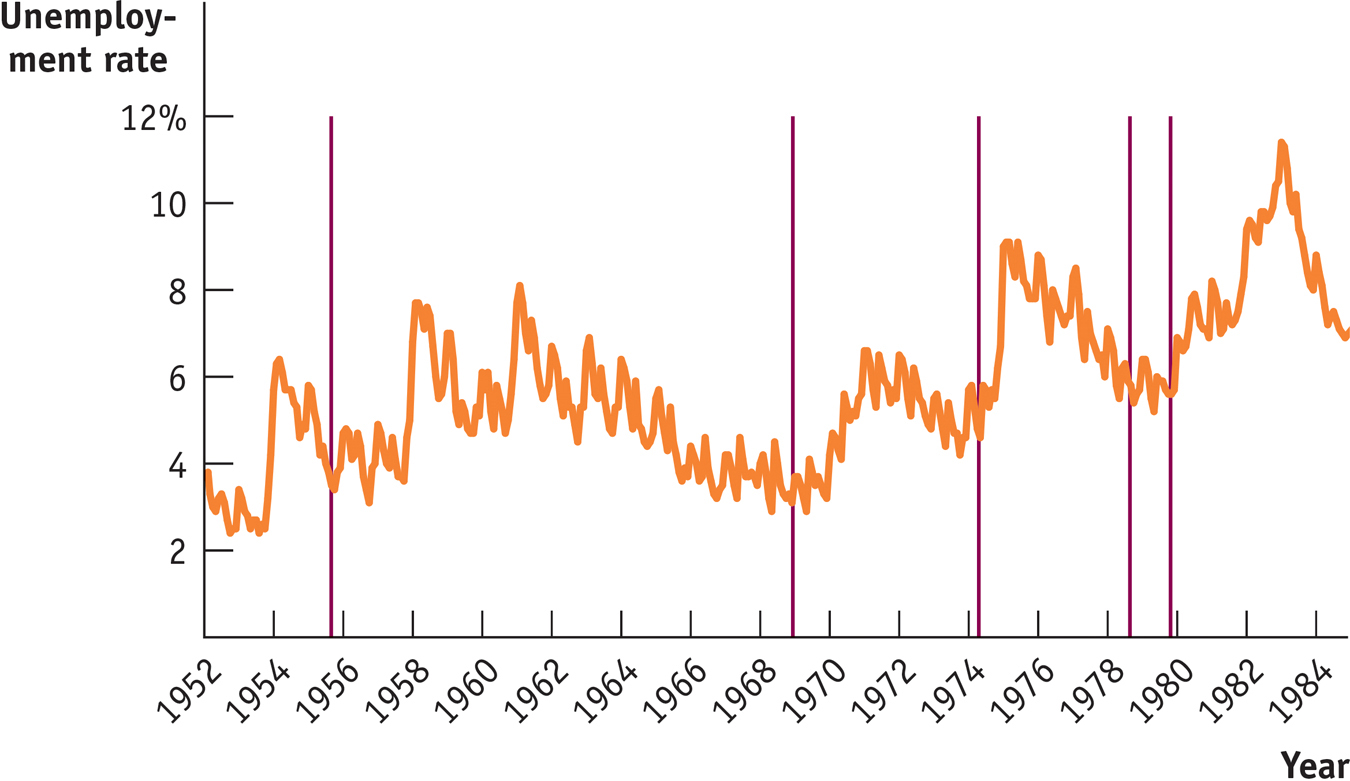

Figure 15-10 shows the unemployment rate between 1952 and 1984 and also identifies five dates on which, according to Romer and Romer, the Fed decided that it wanted a recession (the vertical lines). In four out of the five cases, the decision to contract the economy was followed, after a modest lag, by a rise in the unemployment rate. On average, Romer and Romer found, the unemployment rate rises by 2 percentage points after the Fed decides that unemployment needs to go up.

So yes, the Fed gets what it wants.

Quick Review

The Federal Reserve can use expansionary monetary policy to increase aggregate demand and contractionary monetary policy to reduce aggregate demand. The Federal Reserve and other central banks generally try to tame the business cycle while keeping the inflation rate low but positive.

Under a Taylor rule for monetary policy, the target federal funds rate rises when there is high inflation and either a positive output gap or very low unemployment; it falls when there is low or negative inflation and either a negative output gap or high unemployment.

In contrast, some central banks set monetary policy by inflation targeting, a forward-

looking policy rule, rather than by using the Taylor rule, a backward- looking policy rule. Although inflation targeting has the benefits of transparency and accountability, some think it is too restrictive. Until 2008, the Fed followed a loosely defined Taylor rule. Starting in early 2012, it began inflation targeting with a target of 2% per year. There is a zero lower bound for interest rates—they cannot fall below zero—

that limits the power of monetary policy. Because it is subject to fewer lags than fiscal policy, monetary policy is the main tool for macroeconomic stabilization.

15-3

Question 15.6

Suppose the economy is currently suffering from an output gap and the Federal Reserve uses an expansionary monetary policy to close that gap. Describe the short-

run effect of this policy on the following. The money supply curve

The equilibrium interest rate

Investment spending

Consumer spending

Aggregate output

Question 15.7

In setting monetary policy, which central bank—

one that operates according to a Taylor rule or one that operates by inflation targeting— is likely to respond more directly to a financial crisis? Explain.

Solutions appear at back of book.