Short-Run and Long-Run Effects of an Increase in the Money Supply

To analyze the long-run effects of monetary policy, it’s helpful to think of the central bank as choosing a target for the money supply rather than the interest rate. In assessing the effects of an increase in the money supply, we return to the analysis of the long-run effects of an increase in aggregate demand, first introduced in Chapter 12.

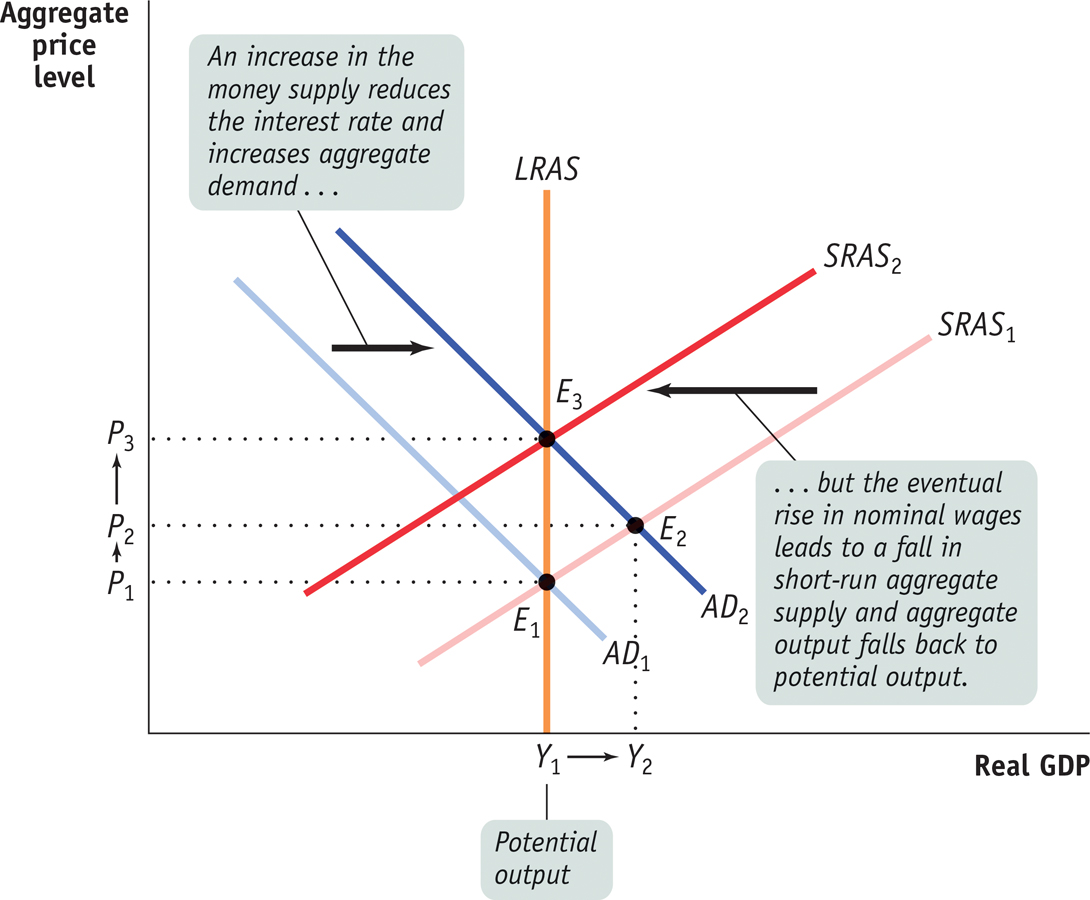

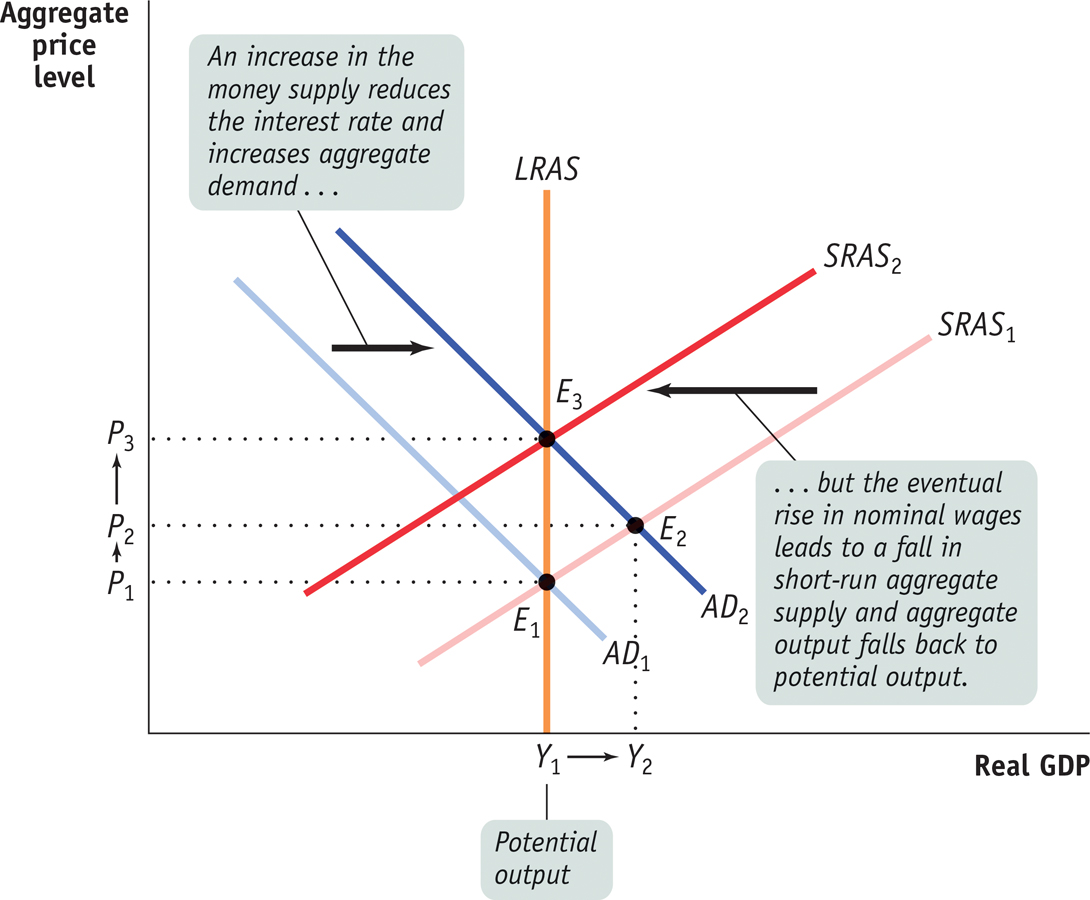

Figure 15-11 shows the short-run and long-run effects of an increase in the money supply when the economy begins at potential output, Y1. The initial short-run aggregate supply curve is SRAS1, the long-run aggregate supply curve is LRAS, and the initial aggregate demand curve is AD1. The economy’s initial equilibrium is at E1, a point of both short-run and long-run macroeconomic equilibrium because it is on both the short-run and the long-run aggregate supply curves. Real GDP is at potential output, Y1.

The Short-Run and Long-Run Effects of an Increase in the Money Supply When the economy is already at potential output, an increase in the money supply generates a positive short-run effect, but no long-run effect, on real GDP.

Here, the economy begins at E1, a point of short-run and long-run macroeconomic equilibrium. An increase in the money supply shifts the AD curve rightward, and the economy moves to a new short-run macroeconomic equilibrium at E2 and a new real GDP of Y2. But E2 is not a long-run equilibrium: Y2 exceeds potential output, Y1, leading over time to an increase in nominal wages. In the long run, the increase in nominal wages shifts the short-run aggregate supply curve leftward, to a new position at SRAS2.

The economy reaches a new short-run and long-run macroeconomic equilibrium at E3 on the LRAS curve, and output falls back to potential output, Y1. When the economy is already at potential output, the only long-run effect of an increase in the money supply is an increase in the aggregate price level from P1 to P3.

Now suppose there is an increase in the money supply. Other things equal, an increase in the money supply reduces the interest rate, which increases investment spending, which leads to a further rise in consumer spending, and so on. So an increase in the money supply increases the quantity of goods and services demanded, shifting the AD curve rightward, to AD2. In the short run, the economy moves to a new short-run macroeconomic equilibrium at E2. The price level rises from P1 to P2, and real GDP rises from Y1 to Y2. That is, both the aggregate price level and aggregate output increase in the short run.

But the aggregate output level, Y2, is above potential output. As a result, nominal wages will rise over time, causing the short-run aggregate supply curve to shift leftward. This process stops only when the SRAS curve ends up at SRAS2 and the economy ends up at point E3, a point of both short-run and long-run macroeconomic equilibrium. The long-run effect of an increase in the money supply, then, is that the aggregate price level has increased from P1 to P3, but aggregate output is back at potential output, Y1. In the long run, a monetary expansion raises the aggregate price level but has no effect on real GDP.

We won’t describe the effects of a monetary contraction in detail, but the same logic applies. In the short run, a fall in the money supply leads to a fall in aggregate output as the economy moves down the short-run aggregate supply curve. In the long run, however, the monetary contraction reduces only the aggregate price level, and real GDP returns to potential output.