Changes in the Money Supply and the Interest Rate in the Long Run

In the short run, an increase in the money supply leads to a fall in the interest rate, and a decrease in the money supply leads to a rise in the interest rate. In the long run, however, changes in the money supply don’t affect the interest rate.

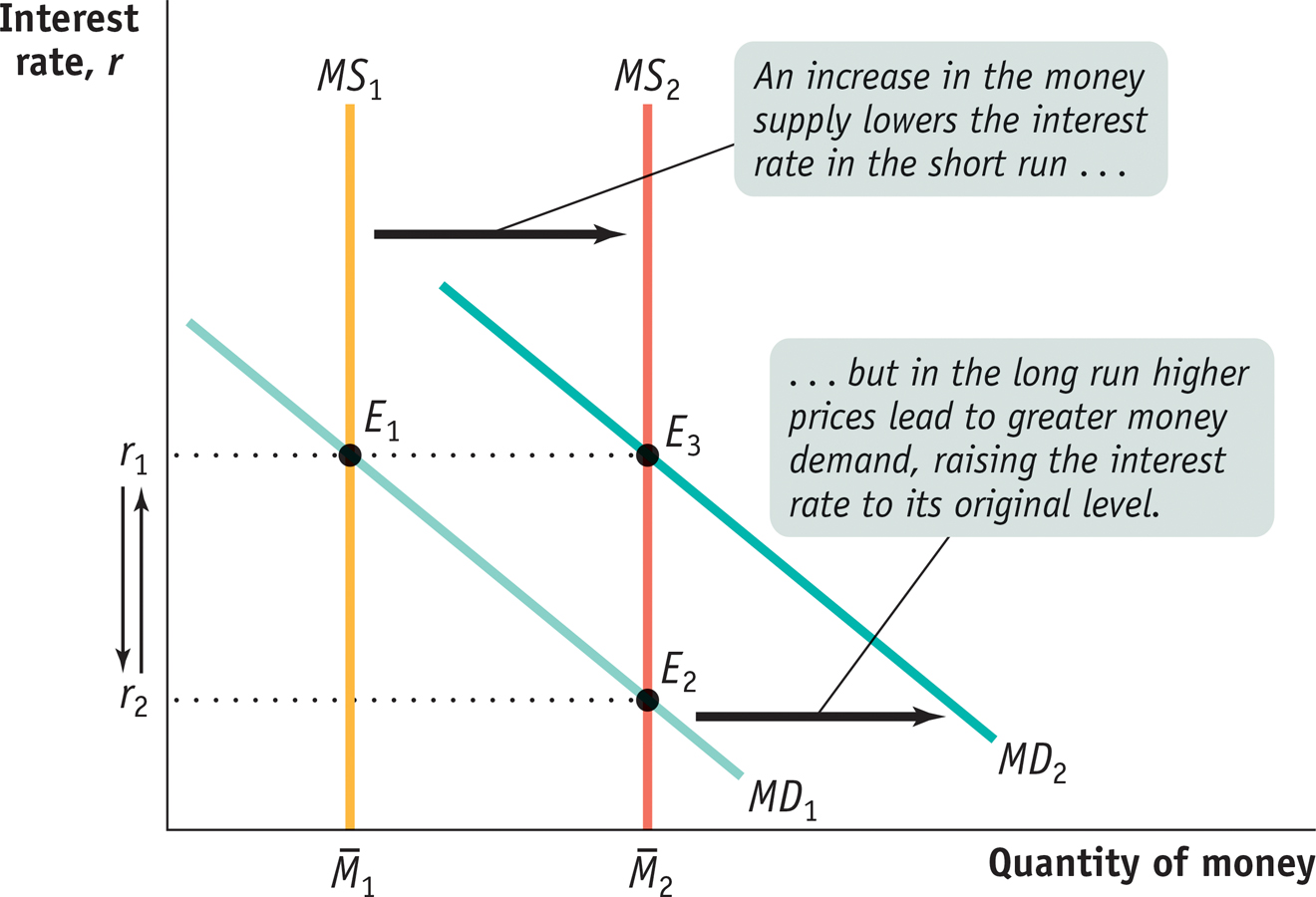

Figure 15-12 shows why. It shows the money supply curve and the money demand curve before and after the Fed increases the money supply. We assume that the economy is initially at E1, in long- . The initial equilibrium interest rate, determined by the intersection of the money demand curve MD1 and the money supply curve MS1, is r1.

. The initial equilibrium interest rate, determined by the intersection of the money demand curve MD1 and the money supply curve MS1, is r1.

to

to  pushes the interest rate down from r1 to r2 and the economy moves to E2, a short-

pushes the interest rate down from r1 to r2 and the economy moves to E2, a short-Now suppose the money supply increases from  to

to  . In the short run, the economy moves from E1 to E2 and the interest rate falls from r1 to r2. Over time, however, the aggregate price level rises, and this raises money demand, shifting the money demand curve rightward from MD1 to MD2. The economy moves to a new long-

. In the short run, the economy moves from E1 to E2 and the interest rate falls from r1 to r2. Over time, however, the aggregate price level rises, and this raises money demand, shifting the money demand curve rightward from MD1 to MD2. The economy moves to a new long-

And it turns out that the long-

So a 50% increase in the money supply raises the aggregate price level by 50%, which increases the quantity of money demanded at any given interest rate by 50%. As a result, the quantity of money demanded at the initial interest rate, r1, rises exactly as much as the money supply—

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: International Evidence of Monetary Neutrality

International Evidence of Monetary Neutrality

These days monetary policy is quite similar among wealthy countries. Each major nation (or, in the case of the euro, the euro area) has a central bank that is insulated from political pressure. All of these central banks try to keep the aggregate price level roughly stable, which usually means inflation of at most 2% to 3% per year.

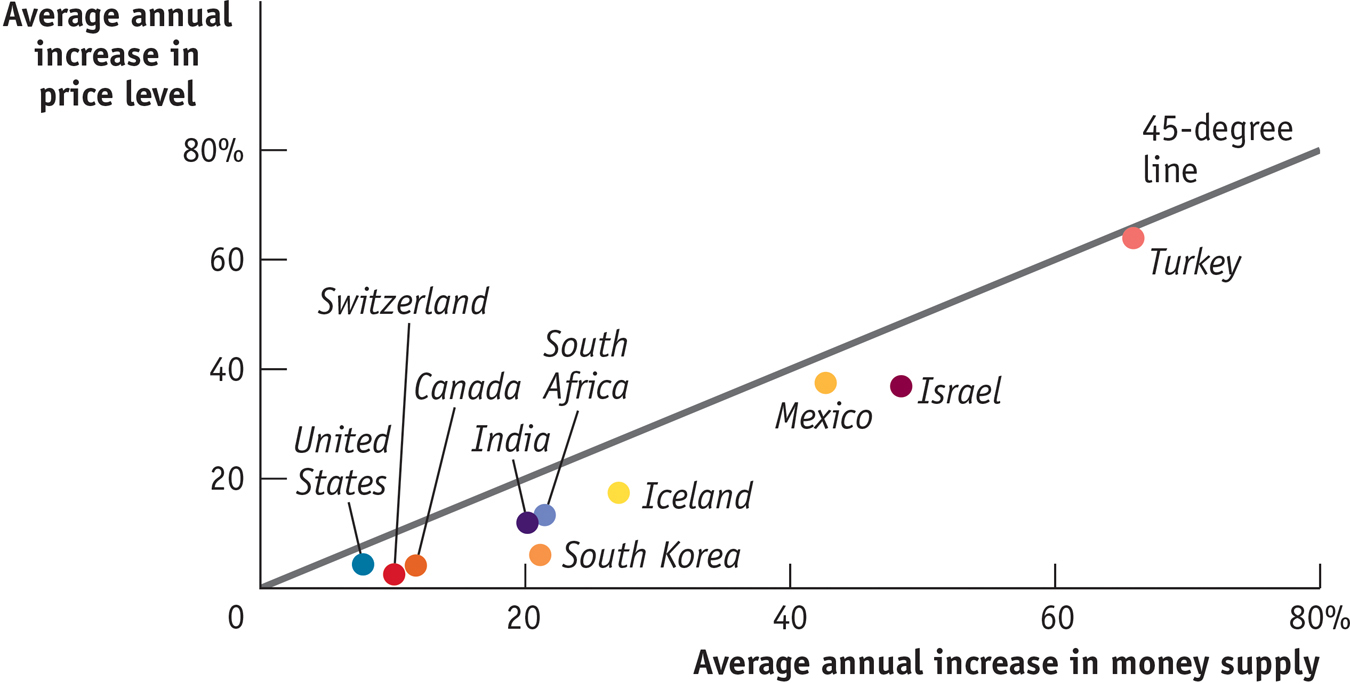

But if we look at a longer period and a wider group of countries, we see large differences in the growth of the money supply. Between 1970 and the present, the money supply rose only a few percent per year in some countries, such as Switzerland and the United States, but rose much more rapidly in some poorer countries, such as South Africa. These differences allow us to see whether it is really true that increases in the money supply lead, in the long run, to equal percent rises in the aggregate price level.

Figure 15-13 shows the annual percentage increases in the money supply and average annual increases in the aggregate price level—

In fact, the relationship isn’t exact, because other factors besides money affect the aggregate price level. But the scatter of points clearly lies close to a 45-

Quick Review

According to the concept of monetary neutrality, changes in the money supply do not affect real GDP, they only affect the aggregate price level. Economists believe that money is neutral in the long run.

In the long run, the equilibrium interest rate in the economy is unaffected by changes in the money supply.

15-4

Question 15.8

Assume the central bank increases the quantity of money by 25%, even though the economy is initially in both short-

run and long- run macroeconomic equilibrium. Describe the effects, in the short run and in the long run (giving numbers where possible), on the following. Aggregate output

Aggregate price level

Interest rate

Question 15.9

Why does monetary policy affect the economy in the short run but not in the long run?

Solutions appear at back of book.

PIMCO Bets on Cheap Money

Pacific Investment Management Company, generally known as PIMCO, is one of the world’s largest investment companies. Among other things, it runs PIMCO Total Return, the world’s largest mutual fund. Bill Gross, who headed PIMCO from 1971 until 2014, was legendary for his ability to predict trends in financial markets, especially bond markets, where PIMCO does much of its investing.

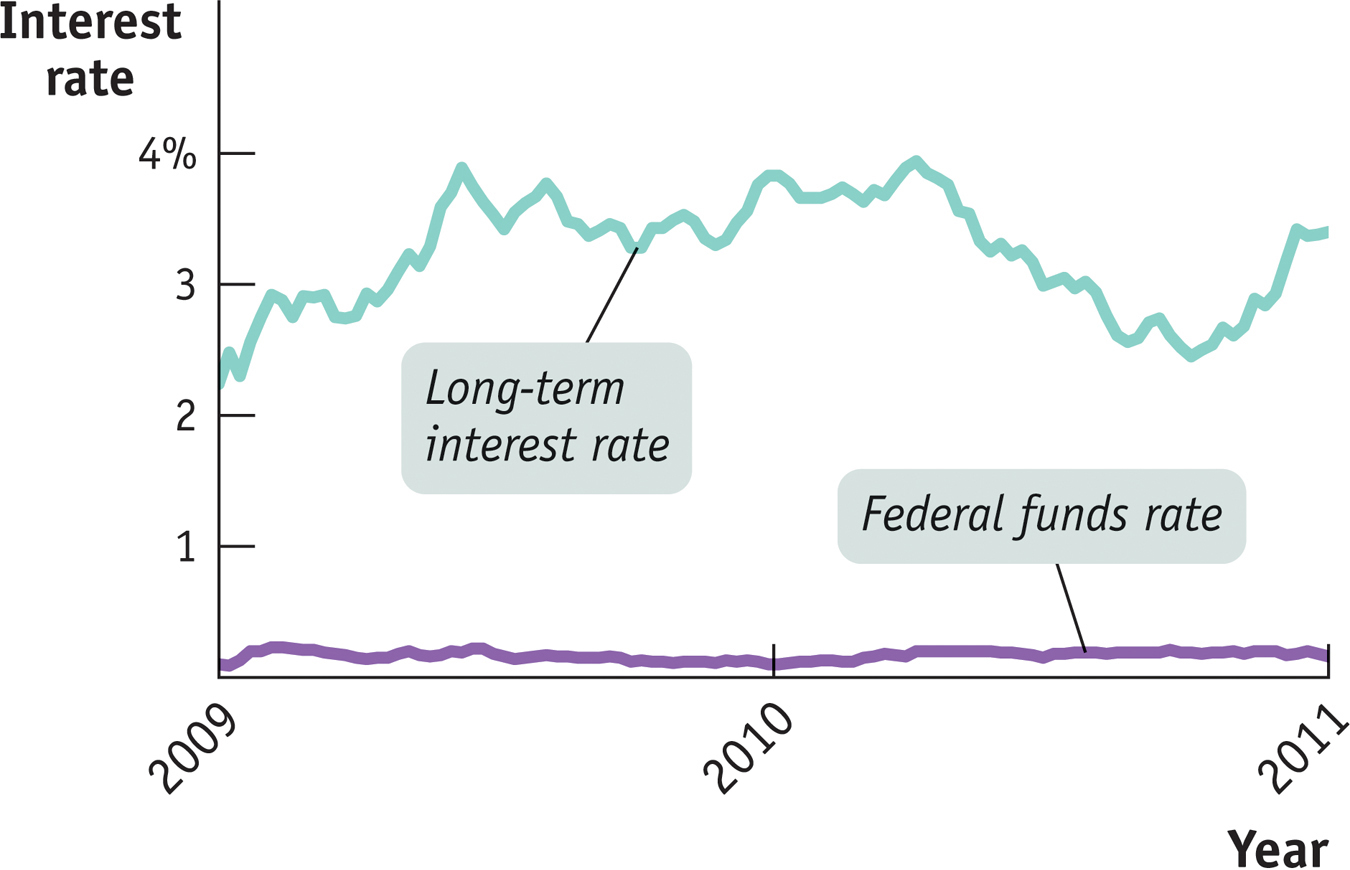

In the fall of 2009, Gross decided to put more of PIMCO’s assets into long-

What lay behind PIMCO’s bet? Gross explained the firm’s thinking in his September 2009 commentary. He suggested that unemployment was likely to stay high and inflation low. “Global policy rates,” he asserted—

PIMCO’s view was in sharp contrast to those of other investors: Morgan Stanley expected long-

Who was right? PIMCO, mostly. As Figure 15-14 shows, the federal funds rate stayed near zero, and long-

Bill Gross’s foresight, however, was a lot less accurate in 2011. Anticipating a significantly stronger U.S. economy by mid-

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 15.10

Why did PIMCO’s view that unemployment would stay high and inflation low lead to a forecast that policy interest rates would remain low for an extended period?

Question 15.11

Why would low policy rates suggest low long-

Question 15.12

What might have caused long-