The Consequences of Banking Crises

If banking crises affected only banks, they wouldn’t be as serious a concern. But banking crises are almost always associated with recessions, and severe banking crises are associated with the worst economic slumps. Furthermore, history shows that recessions caused in part by banking crises inflict sustained economic damage, with economies taking years to recover.

Banking Crises, Recessions, and Recovery

A severe banking crisis is one in which a large fraction of the banking system either fails outright (that is, goes bankrupt) or suffers a major loss of confidence and must be bailed out by the government. Such crises almost invariably lead to deep recessions, which are usually followed by slow recoveries.

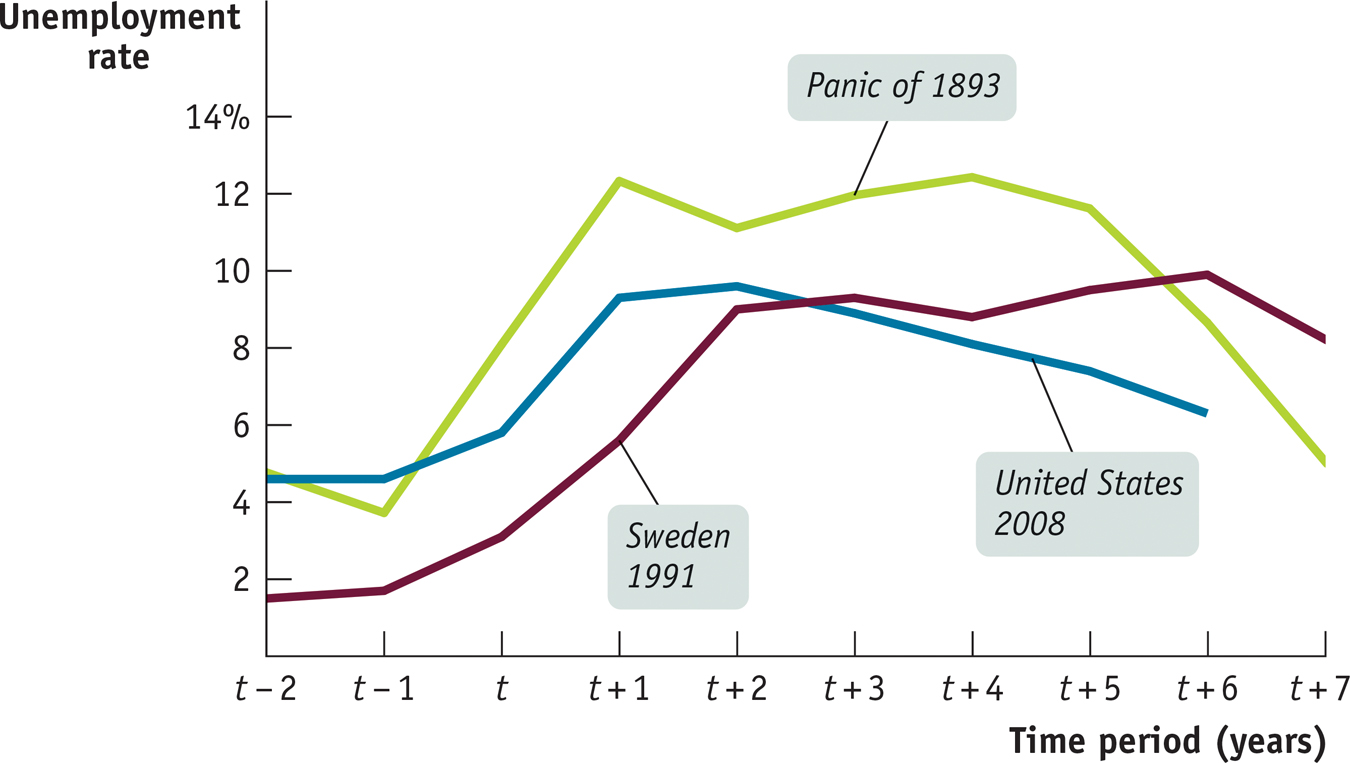

Figure 17-2 illustrates this phenomenon by tracking unemployment in the aftermath of three banking crises widely separated in space and time: the Panic of 1893, the Swedish banking crisis of 1991, and the American financial crisis of 2008 that spawned the Great Recession. In the figure, t represents the year of the crisis: 1893 for the United States, 1991 for Sweden. As the figure shows, these three crises, spanning over 100 years and continents apart, produced similarly devastating results: unemployment shot up and came down only slowly and erratically so that the number of jobless remained high by pre-

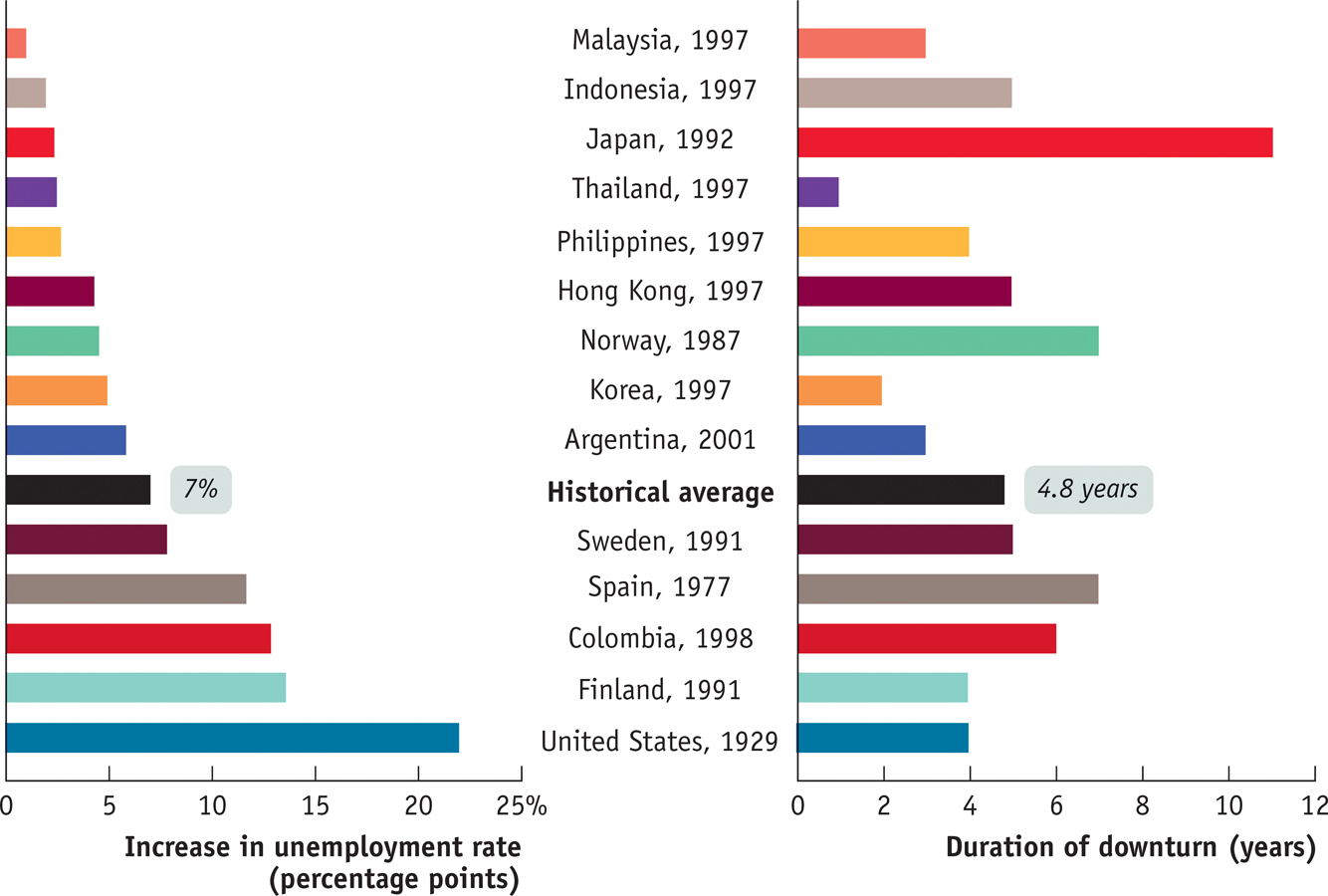

These historical examples are typical. Figure 17-3, taken from a widely cited study by the economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, compares employment performance in the wake of a number of severe banking crises. The bars on the left show the rise in the unemployment rate during and following the crisis; the bars on the right show the time it took before unemployment began to fall. The numbers are shocking: on average, severe banking crises have been followed by a 7-

Why Are Banking-Crisis Recessions So Bad?

It’s not difficult to see why banking crises normally lead to recessions. There are three main reasons: a credit crunch arising from reduced availability of credit, financial distress caused by a debt overhang, and the loss of monetary policy effectiveness.

In a credit crunch, potential borrowers either can’t get credit at all or must pay very high interest rates.

Credit crunch. The disruption of the banking system typically leads to a reduction in the availability of credit, called a credit crunch, in which potential borrowers either can’t get credit at all or must pay very high interest rates. Unable to borrow or unwilling to pay higher interest rates, businesses and consumers cut back on spending, pushing the economy into a recession.

A debt overhang occurs when a vicious circle of deleveraging leaves a borrower with high debt but diminished assets.

Debt overhang. A banking crisis typically pushes down the prices of many assets through a vicious circle of deleveraging, as distressed borrowers try to sell assets to raise cash, pushing down asset prices and causing further financial distress. As we have already seen, deleveraging is a factor in the spread of the crisis, lowering the value of the assets banks hold on their balance sheets and so undermining their solvency. It also creates problems for other players in the economy. To take an example all too familiar from recent events, falling housing prices can leave consumers substantially poorer, especially because they are still stuck with the debt they incurred to buy their homes. A banking crisis, then, tends to leave consumers and businesses with a debt overhang: high debt but diminished assets. Like a credit crunch, this also leads to a fall in spending and a recession as consumers and businesses cut back in order to reduce their debt and rebuild their assets.

Loss of monetary policy effectiveness. A key feature of banking-

crisis recessions is that when they occur, monetary policy— the main tool of policy makers for fighting negative demand shocks caused by a fall in consumer and investment spending— loses much of its effectiveness. The ineffectiveness of monetary policy makes banking- crisis recessions especially severe and long- lasting.

Recall from Chapter 14 how the Fed normally responds to a recession: it engages in open-

Under normal conditions, this policy response is highly effective. In the aftermath of a banking crisis, though, the whole process tends to break down. Banks, fearing runs by depositors or a loss of confidence by their creditors, tend to hold on to excess reserves rather than lend them out. Meanwhile, businesses and consumers, finding themselves in financial difficulty due to the plunge in asset prices, may be unwilling to borrow even if interest rates fall. As a result, even very low interest rates may not be enough to push the economy back to full employment.

In the previous chapter we described the problem of the economy’s falling into a liquidity trap, when even pushing short-

The inability of the usual tools of monetary policy to offset the macroeconomic devastation caused by banking crises is the major reason such crises produce deep, prolonged slumps. The obvious solution is to look for other policy tools. In fact, governments do typically take a variety of special steps when banks are in crisis.

Governments Step In

Before the Great Depression, policy makers often adopted a laissez-

They act as the lender of last resort.

They offer guarantees to depositors and others with claims on banks.

In an extreme crisis, a central bank will step in and provide financing to private credit markets.

A lender of last resort is an institution, usually a country’s central bank, that provides funds to financial institutions when they are unable to borrow from the private credit markets.

1. Lender of Last Resort An institution, usually a country’s central bank, that provides funds to financial institutions when they are unable to borrow from the private credit markets is a lender of last resort. In particular, the central bank can provide cash to a bank that is facing a run by depositors but is fundamentally solvent, making it unnecessary for the bank to engage in fire sales of its assets to raise cash. This acts as a lifeline, working to prevent a loss of confidence in the bank’s solvency from turning into a self-

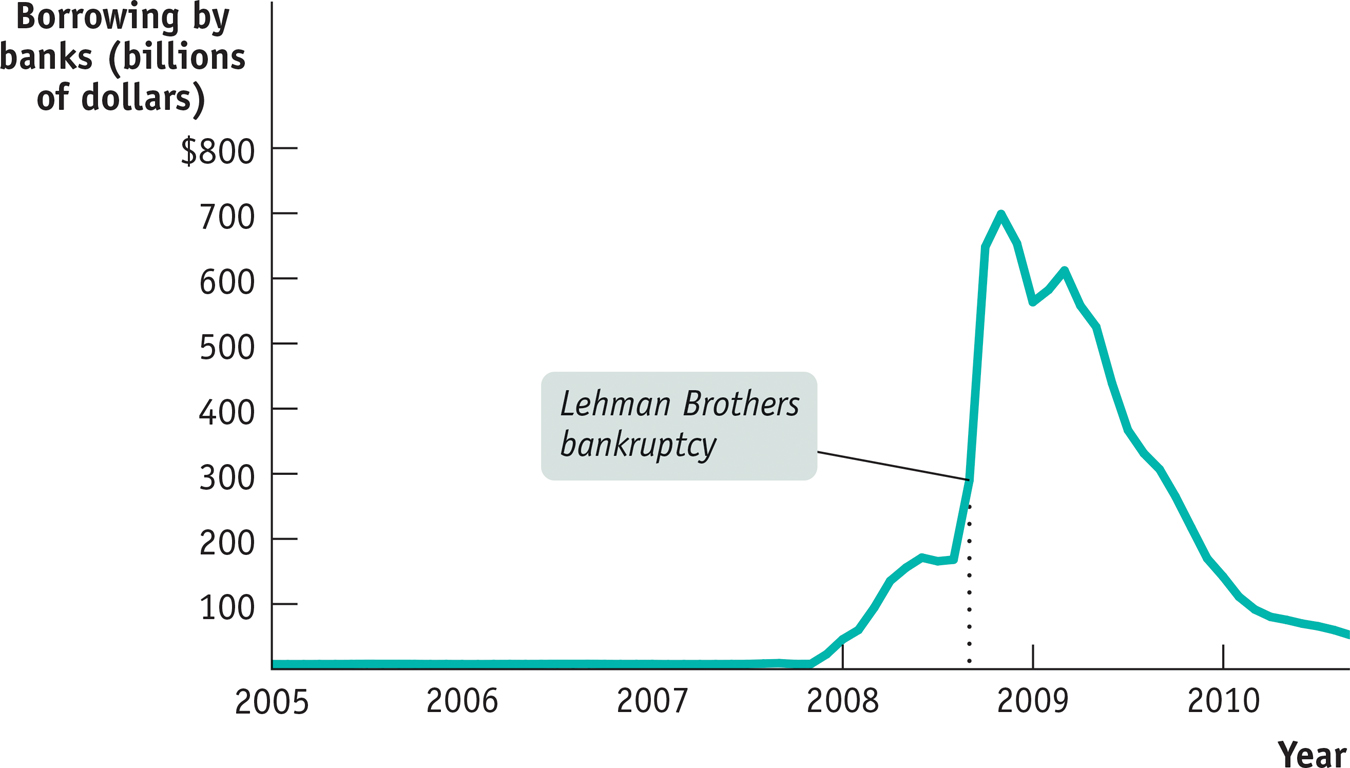

Did the Federal Reserve act as a lender of last resort in the 2008 financial crisis? Very much so. Figure 17-4 shows borrowing by banks from the Fed between 2005 and 2010: commercial banks borrowed negligible amounts from the central bank before the crisis, but their borrowing rose to $700 billion in the months following Lehman’s failure. To get a sense of how large this borrowing was, note that total bank reserves before the crisis were less than $50 billion—

2. Government Guarantees There are limits, though, to how much a lender of last resort can accomplish: it can’t restore confidence in a bank if there is good reason to believe the bank is fundamentally insolvent. If the public believes that the bank’s assets aren’t worth enough to cover its debts even if it doesn’t have to sell these assets on short notice, a lender of last resort isn’t going to help much. And in major banking crises there are often good reasons to believe that many banks are truly bankrupt.

As we have already learned, in such cases governments often step in to guarantee banks’ liabilities. In 2007, a bank run hit the British bank, Northern Rock, ceasing only when the British government stepped in and guaranteed all deposits at the bank, regardless of size. Ireland’s government eventually stepped in to guarantee repayment of not just deposits at all of the nation’s banks, but all bank debts. Sweden did the same thing after its 1991 banking crisis.

When governments take on banks’ risk, they often demand a quid pro quo; namely, they often take ownership of the banks they are rescuing—

These government takeovers are almost always temporary. In general, modern governments want to save banks, not run them. So governments eventually reprivatize nationalized banks, selling them to private buyers, as soon as they believe they can.

3. Provider of Direct Financing As we learned in Chapter 14, during the depths of the 2008 financial crisis the Federal Reserve expanded its operations beyond the usual measures of open-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Banks and the Great Depression

Banks and the Great Depression

According to the official business-

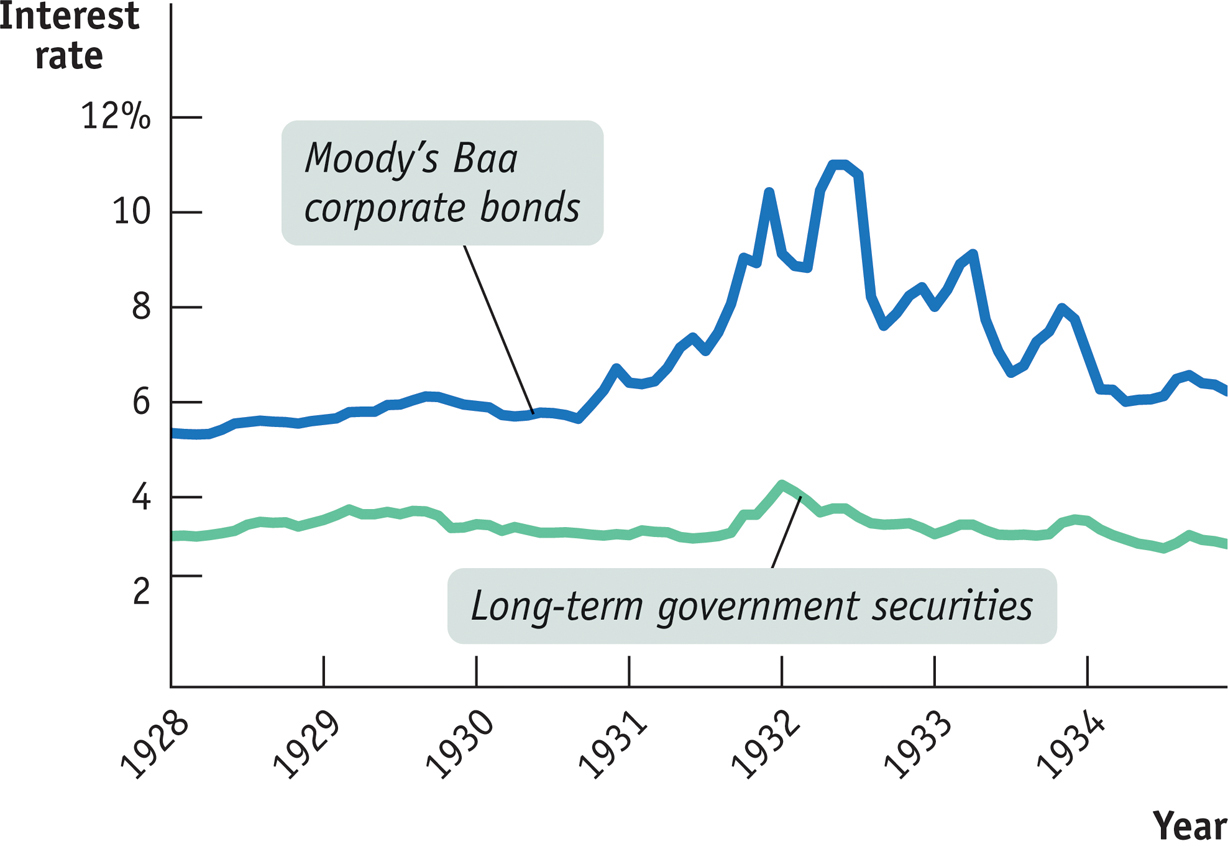

How did the banking crisis hurt the wider economy? Largely by creating a credit crunch, in which businesses in particular either could not borrow or found themselves forced to pay sharply higher interest rates. Figure 17-5 shows one indicator of this credit crunch: the difference between the interest rates—

Baa corporate bonds are those that Moody’s, the credit rating agency, considers “medium-

One striking fact about the banking crisis of the early 1930s is that the Federal Reserve, although it had the legal ability to act as a lender of last resort, largely failed to do so. Nothing like the surge in bank borrowing from the Fed that took place in 2007–

Meanwhile, neither the Fed nor the federal government did anything to rescue failing banks until 1933. So the early 1930s offer a clear example of a banking crisis that policy makers more or less allowed to take its course. It’s not an experience anyone wants to repeat.

Quick Review

Banking crises almost always result in recessions, with severe banking crises associated with the worst economic slumps. Historically, severe banking crises have resulted, on average, in a 7-

percentage- point rise in the unemployment rate. Recessions caused by banking crises are especially severe because they involve a credit crunch, a vicious circle of deleveraging coupled with a debt overhang, leading households and businesses to cut spending, further deepening the downturn.

Slumps induced by bank crises are so severe and prolonged because they make monetary policy ineffective: even though the central bank can lower interest rates, financially distressed households and businesses may still be unwilling to borrow and spend.

Central banks and governments use two main types of policies to limit the damage from a banking crisis: acting as the lender of last resort and offering guarantees that the banks’ liabilities will be repaid. In the aftermath of a bank rescue, governments sometimes nationalize the bank and then later reprivatize it. In an extreme crisis, the central bank will provide direct financing to private credit markets.

17-3

Question 17.4

Explain why the Federal Reserve was able to prevent the crisis of 2008 from turning into another Great Depression but was unable to prevent the surge in unemployment that occurred.

Question 17.5

Explain why, in the aftermath of a severe banking crisis, a very low interest rate—

even as low as 0%—may be unable to move the economy back to full employment.

Solutions appear at back of book.