Comparative Advantage and Gains from Trade

Among the twelve principles of economics described in Chapter 1 was the principle of gains from trade—the mutual gains that individuals can achieve by specializing in doing different things and trading with one another. Our second illustration of an economic model is a particularly useful model of gains from trade—

One of the most important insights in all of economics is that there are gains from trade—

How can we model the gains from trade? Let’s stay with our aircraft example and once again imagine that the United States is a one-

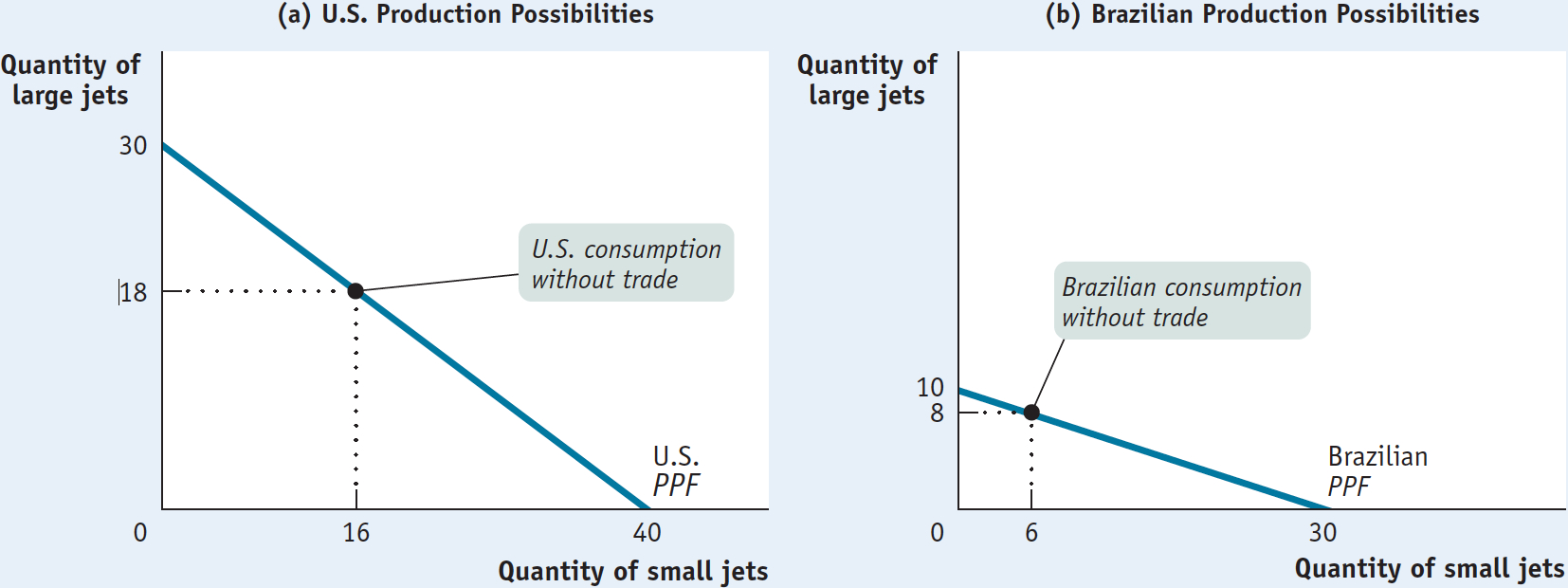

In our example, the only two goods produced are large jets and small jets. Both countries could produce both kinds of jets. But as we’ll see in a moment, they can gain by producing different things and trading with each other. For the purposes of this example, let’s return to the simpler case of straight-

Panel (b) of Figure 2-4 shows Brazil’s production possibilities. Like the United States, Brazil’s production possibility frontier is a straight line, implying a constant opportunity cost of a small jet in terms of large jets. Brazil’s production possibility frontier has a constant slope of -⅓. Brazil can’t produce as much of anything as the United States can: at most it can produce 30 small jets or 10 large jets. But it is relatively better at manufacturing small jets than the United States; whereas the United States sacrifices ¾ of a large jet per small jet produced, for Brazil the opportunity cost of a small jet is only ⅓ of a large jet. Table 2-1 summarizes the two countries’ opportunity costs of small jets and large jets.

Now, the United States and Brazil could each choose to make their own large and small jets, not trading any airplanes and consuming only what each produced within its own country. (A country “consumes” an airplane when it is owned by a domestic resident.) Let’s suppose that the two countries start out this way and make the consumption choices shown in Figure 2-4: in the absence of trade, the United States produces and consumes 16 small jets and 18 large jets per year, while Brazil produces and consumes 6 small jets and 8 large jets per year.

But is this the best the two countries can do? No, it isn’t. Given that the two producers—

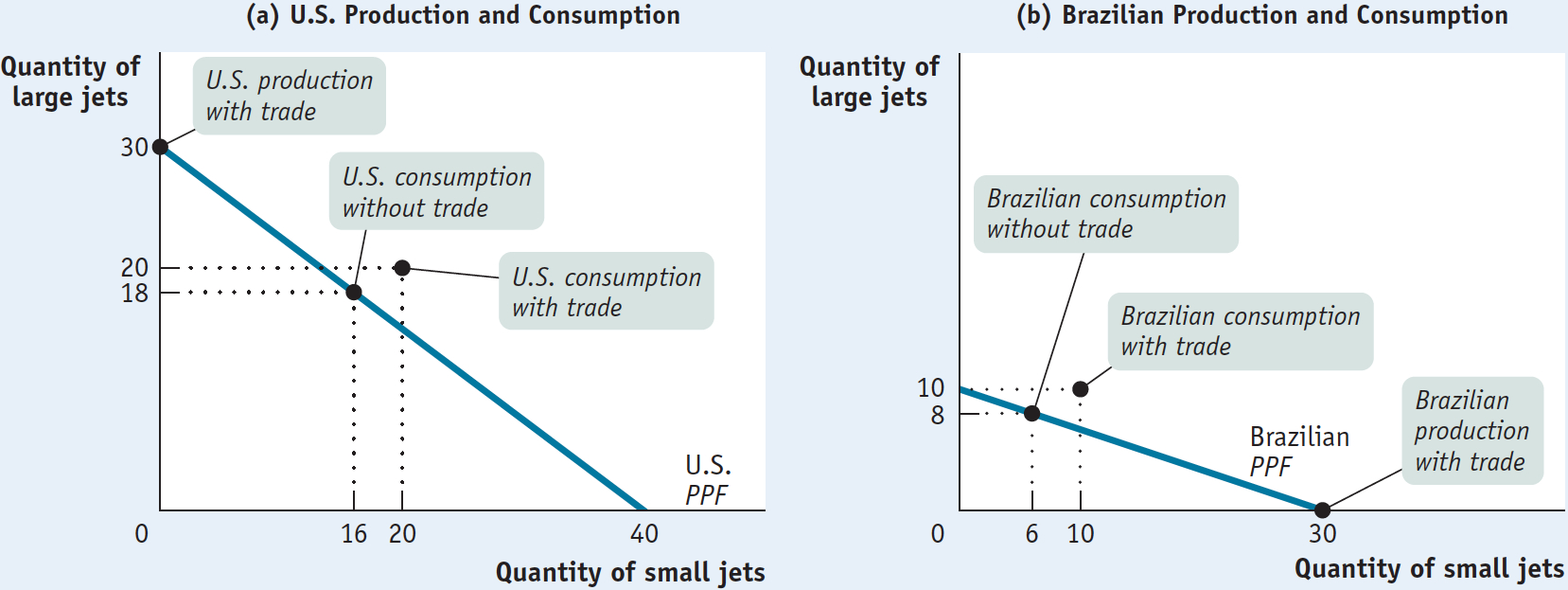

Table 2-2 shows how such a deal works: the United States specializes in the production of large jets, manufacturing 30 per year, and sells 10 to Brazil. Meanwhile, Brazil specializes in the production of small jets, producing 30 per year, and sells 20 to the United States. The result is shown in Figure 2-5. The United States now consumes more of both small jets and large jets than before: instead of 16 small jets and 18 large jets, it now consumes 20 small jets and 20 large jets. Brazil also consumes more, going from 6 small jets and 8 large jets to 10 small jets and 10 large jets. As Table 2-2 also shows, both the United States and Brazil reap gains from trade, consuming more of both types of plane than they would have without trade.

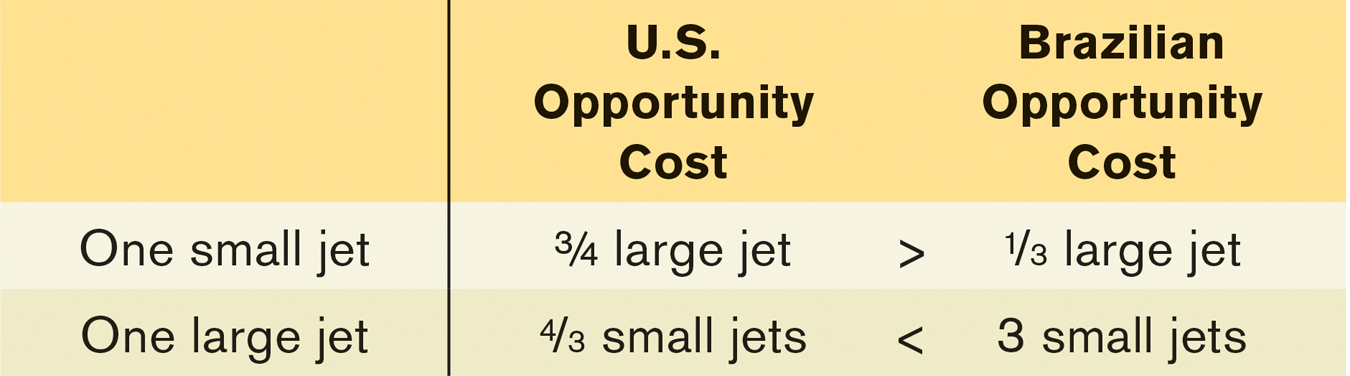

Both countries are better off when they each specialize in what they are good at and trade. It’s a good idea for the United States to specialize in the production of large jets because its opportunity cost of a large jet is smaller than Brazil’s:  < 3. Correspondingly, Brazil should specialize in the production of small jets because its opportunity cost of a small jet is smaller than the United States: ⅓ < ¾.

< 3. Correspondingly, Brazil should specialize in the production of small jets because its opportunity cost of a small jet is smaller than the United States: ⅓ < ¾.

A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good or service if its opportunity cost of producing the good or service is lower than other countries’. Likewise, an individual has a comparative advantage in producing a good or service if his or her opportunity cost of producing the good or service is lower than for other people.

What we would say in this case is that the United States has a comparative advantage in the production of large jets and Brazil has a comparative advantage in the production of small jets. A country has a comparative advantage in producing something if the opportunity cost of that production is lower for that country than for other countries. The same concept applies to firms and people: a firm or an individual has a comparative advantage in producing something if its, his, or her opportunity cost of production is lower than for others.

One point of clarification before we proceed further. You may have wondered why the United States traded 10 large jets to Brazil in return for 20 small jets. Why not some other deal, like trading 10 large jets for 12 small jets? The answer to that question has two parts. First, there may indeed be other trades that the United States and Brazil might agree to. Second, there are some deals that we can safely rule out—

To understand why, reexamine Table 2-1 and consider the United States first. Without trading with Brazil, the U.S. opportunity cost of a small jet is ¾ of a large jet. So it’s clear that the United States will not accept any trade that requires it to give up more than ¾ of a large jet for a small jet. Trading 10 jets in return for 12 small jets would require the United States to pay an opportunity cost of  = ⅚ of a large jet for a small jet. Because ⅚ > than ¾, this is a deal that the United States would reject. Similarly, Brazil won’t accept a trade that gives it less than ⅓ of a large jet for a small jet.

= ⅚ of a large jet for a small jet. Because ⅚ > than ¾, this is a deal that the United States would reject. Similarly, Brazil won’t accept a trade that gives it less than ⅓ of a large jet for a small jet.

The point to remember is that the United States and Brazil will be willing to trade only if the “price” of the good each country obtains in the trade is less than its own opportunity cost of producing the good domestically. Moreover, this is a general statement that is true whenever two parties—

While our story clearly simplifies reality, it teaches us some very important lessons that apply to the real economy, too.

First, the model provides a clear illustration of the gains from trade: through specialization and trade, both countries produce more and consume more than if they were self-

Second, the model demonstrates a very important point that is often overlooked in real-

A country has an absolute advantage in producing a good or service if the country can produce more output per worker than other countries. Likewise, an individual has an absolute advantage in producing a good or service if he or she is better at producing it than other people. Having an absolute advantage is not the same thing as having a comparative advantage.

Crucially, in our example it doesn’t matter if, as is probably the case in real life, U.S. workers are just as good as or even better than Brazilian workers at producing small jets. Suppose that the United States is actually better than Brazil at all kinds of aircraft production. In that case, we would say that the United States has an absolute advantage in both large-

But we’ve just seen that the United States can indeed benefit from trading with Brazil because comparative, not absolute, advantage is the basis for mutual gain. It doesn’t matter whether it takes Brazil more resources than the United States to make a small jet; what matters for trade is that for Brazil the opportunity cost of a small jet is lower than the U.S. opportunity cost. So Brazil, despite its absolute disadvantage, even in small jets, has a comparative advantage in the manufacture of small jets. Meanwhile the United States, which can use its resources most productively by manufacturing large jets, has a comparative disadvantage in manufacturing small jets.