Transactions: The Circular-Flow Diagram

Trade takes the form of barter when people directly exchange goods or services that they have for goods or services that they want.

The model economies that we’ve studied so far—

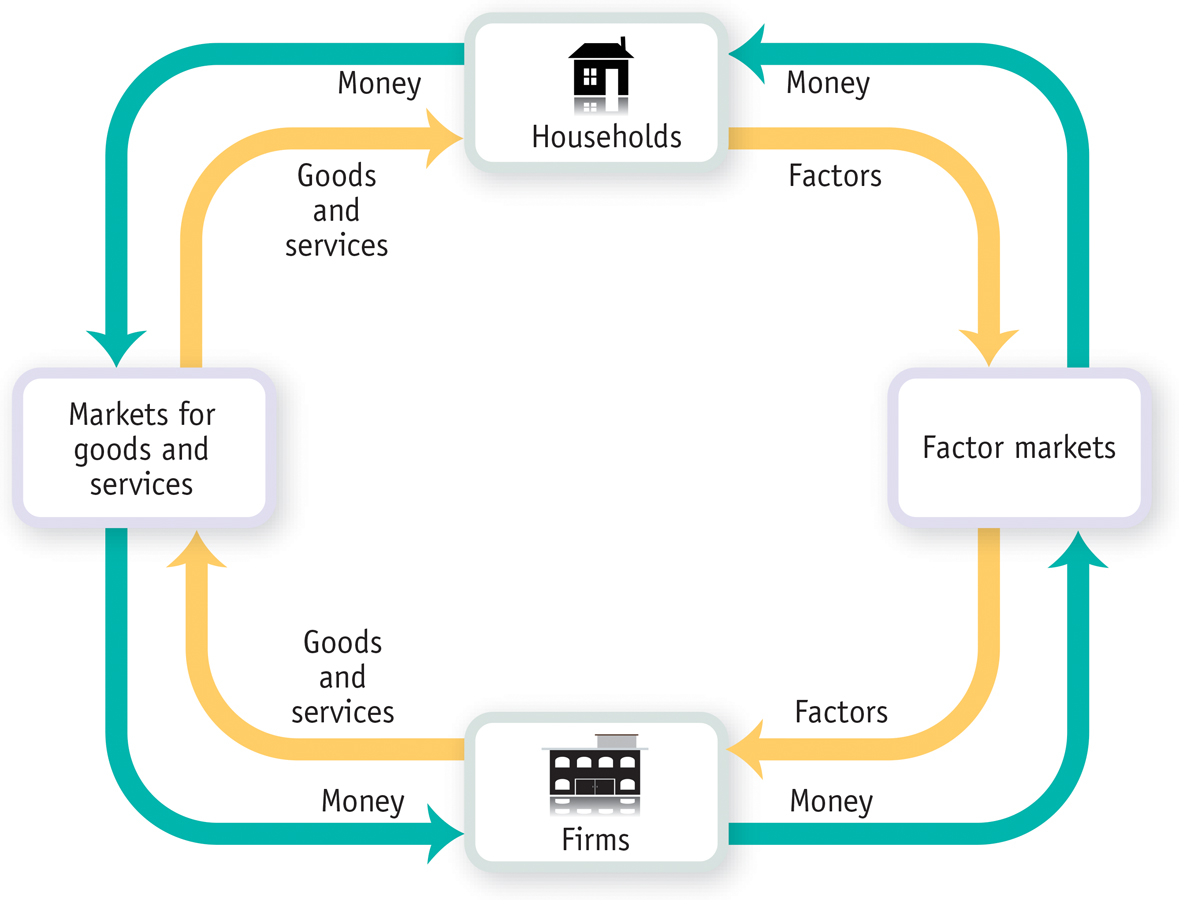

And they both sell and buy a lot of different things. The U.S. economy is a vastly complex entity, with more than a hundred million workers employed by millions of companies, producing millions of different goods and services. Yet you can learn some very important things about the economy by considering the simple graphic shown in Figure 2-6, the circular-

The circular-

A household is a person or a group of people that share their income.

The simplest circular-

A firm is an organization that produces goods and services for sale.

Firms sell goods and services that they produce to households in markets for goods and services.

As you can see in Figure 2-6, there are two kinds of markets in this simple economy. On one side (here the left side) there are markets for goods and services in which households buy the goods and services they want from firms. This produces a flow of goods and services to households and a return flow of money to firms.

Firms buy the resources they need to produce goods and services in factor markets.

On the right side, there are factor markets in which firms buy the resources they need to produce goods and services. Recall from earlier that the main factors of production are land, labor, physical capital, and human capital.

An economy’s income distribution is the way in which total income is divided among the owners of the various factors of production.

The factor market most of us know best is the labor market, in which workers sell their services. In addition, we can think of households as owning and selling the other factors of production to firms. For example, when a firm buys physical capital in the form of machines, the payment ultimately goes to the households that own the machine-

The circular-

In the real world, the distinction between firms and households isn’t always that clear-

cut. Consider a small, family- run business— a farm, a shop, a small hotel. Is this a firm or a household? A more complete picture would include a separate box for family businesses. Many of the sales firms make are not to households but to other firms; for example, steel companies sell mainly to other companies such as auto manufacturers, not to households. A more complete picture would include these flows of goods, services, and money within the business sector.

The figure doesn’t show the government, which in the real world diverts quite a lot of money out of the circular flow in the form of taxes but also injects a lot of money back into the flow in the form of spending.

Figure 2-6, in other words, is by no means a complete picture either of all the types of inhabitants of the real economy or of all the flows of money and physical items that take place among these inhabitants.

Despite its simplicity, the circular-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Rich Nation, Poor Nation

Rich Nation, Poor Nation

Try taking off your clothes—

Why are these countries so much poorer than we are? The immediate reason is that their economies are much less productive—firms in these countries are just not able to produce as much from a given quantity of resources as comparable firms in the United States or other wealthy countries. Why countries differ so much in productivity is a deep question—

But if the economies of these countries are so much less productive than ours, how is it that they make so much of our clothing? Why don’t we do it for ourselves?

The answer is “comparative advantage.” Just about every industry in Bangladesh is much less productive than the corresponding industry in the United States. But the productivity difference between rich and poor countries varies across goods; it is very large in the production of sophisticated goods like aircraft but not that large in the production of simpler goods like clothing. So Bangladesh’s position with regard to clothing production is like Embraer’s position with respect to producing small jets: it’s not as good at it as Boeing, but it’s the thing Embraer does comparatively well.

Bangladesh, though it is at an absolute disadvantage compared with the United States in almost everything, has a comparative advantage in clothing production. This means that both the United States and Bangladesh are able to consume more because they specialize in producing different things, with Bangladesh supplying our clothing and the United States supplying Bangladesh with more sophisticated goods.

Quick Review

Most economic models are “thought experiments” or simplified representations of reality that rely on the other things equal assumption.

The production possibility frontier model illustrates the concepts of efficiency, opportunity cost, and economic growth.

Every person and every country has a comparative advantage in something, giving rise to gains from trade. Comparative advantage is often confused with absolute advantage.

In the simplest economies people barter rather than transact with money. The circular-

flow diagram illustrates transactions within the economy as flows of goods and services, factors of production, and money between households and firms. These transactions occur in markets for goods and services and factor markets. Ultimately, factor markets determine the economy’s income distribution.

2-1

Question 2.1

True or false? Explain your answer.

An increase in the amount of resources available to Boeing for use in producing Dreamliners and small jets does not change its production possibility frontier.

False. An increase in the resources available to Boeing for use in producing Dreamliners and small jets changes the production possibility frontier by shifting it outward. This is because Boeing can now produce more small jets and Dreamliners than before. In the accompanying figure, the line labeled “Boeing’s original PPF” represents Boeing’s original production possibility frontier, and the line labeled “Boeing’s new PPF” represents the new production possibility frontier that results from an increase in resources available to Boeing.

A technological change that allows Boeing to build more small jets for any amount of Dreamliners built results in a change in its production possibility frontier.

True. A technological change that allows Boeing to build more small jets for any amount of Dreamliners built results in a change in its production possibility frontier. This is illustrated in the accompanying figure: the new production possibility frontier is represented by the line labeled “Boeing’s new PPF,” and the original production frontier is represented by the line labeled “Boeing’s original PPF.” Since the maximum quantity of Dreamliners that Boeing can build is the same as before, the new production possibility frontier intersects the vertical axis at the same point as the original frontier. But since the maximum possible quantity of small jets is now greater than before, the new frontier intersects the horizontal axis to the right of the original frontier.

The production possibility frontier is useful because it illustrates how much of one good an economy must give up to get more of another good regardless of whether resources are being used efficiently.

False. The production possibility frontier illustrates how much of one good an economy must give up to get more of another good only when resources are used efficiently in production. If an economy is producing inefficiently—that is, inside the frontier—then it does not have to give up a unit of one good in order to get another unit of the other good. Instead, by becoming more efficient in production, this economy can have more of both goods.

Question 2.2

In Italy, an automobile can be produced by 8 workers in one day and a washing machine by 3 workers in one day. In the United States, an automobile can be produced by 6 workers in one day and a washing machine by 2 workers in one day.

Which country has an absolute advantage in the production of automobiles? In washing machines?

The United States has an absolute advantage in automobile production because it takes fewer Americans (6) to produce a car in one day than Italians (8). The United States also has an absolute advantage in washing machine production because it takes fewer Americans (2) to produce a washing machine in one day than Italians (3).Which country has a comparative advantage in the production of washing machines? In automobiles?

In Italy the opportunity cost of a washing machine in terms of an automobile is :

:  of a car can be produced with the same number of workers and in the same time it takes to produce 1 washing machine. In the United States the opportunity cost of a washing machine in terms of an automobile is

of a car can be produced with the same number of workers and in the same time it takes to produce 1 washing machine. In the United States the opportunity cost of a washing machine in terms of an automobile is  =

=  :

:  of a car can be produced with the same number of workers and in the same time it takes to produce 1 washing machine. Since

of a car can be produced with the same number of workers and in the same time it takes to produce 1 washing machine. Since  <

<  , the United States has a comparative advantage in the production of washing machines: to produce a washing machine, only

, the United States has a comparative advantage in the production of washing machines: to produce a washing machine, only  of a car must be given up in the United States but

of a car must be given up in the United States but  of a car must be given up in Italy. This means that Italy has a comparative advantage in automobiles. This can be checked as follows. The opportunity cost of an automobile in terms of a washing machine in Italy is

of a car must be given up in Italy. This means that Italy has a comparative advantage in automobiles. This can be checked as follows. The opportunity cost of an automobile in terms of a washing machine in Italy is  , equal to 2

, equal to 2 : 2

: 2 washing machines can be produced with the same number of workers and in the time it takes to produce 1 car in Italy. And the opportunity cost of an automobile in terms of a washing machine in the United States is

washing machines can be produced with the same number of workers and in the time it takes to produce 1 car in Italy. And the opportunity cost of an automobile in terms of a washing machine in the United States is  , equal to 3: 3 washing machines can be produced with the same number of workers and in the time it takes to produce 1 car in the United States. Since 2

, equal to 3: 3 washing machines can be produced with the same number of workers and in the time it takes to produce 1 car in the United States. Since 2 < 3, Italy has a comparative advantage in producing automobiles.

< 3, Italy has a comparative advantage in producing automobiles.What pattern of specialization results in the greatest gains from trade between the two countries?

The greatest gains are realized when each country specializes in producing the good for which it has a comparative advantage. Therefore, the United States should specialize in washing machines and Italy should specialize in automobiles.

Question 2.3

Using the numbers from Table 2-1, explain why the United States and Brazil are willing to engage in a trade of 10 large jets for 15 small jets.

At a trade of 10 U.S. large jets for 15 Brazilian small jets, Brazil gives up less for a large jet than it would if it were building large jets itself. Without trade, Brazil gives up 3 small jets for each large jet it produces. With trade, Brazil gives up only 1.5 small jets for each large jet from the United States. Likewise, the United States gives up less for a small jet than it would if it were producing small jets itself. Without trade, the United States gives up ¾ of a large jet for each small jet. With trade, the United States gives up only of a large jet for each small jet from Brazil.

of a large jet for each small jet from Brazil.Question 2.4

Use the circular-

flow diagram to explain how an increase in the amount of money spent by households results in an increase in the number of jobs in the economy. Describe in words what the circular- flow diagram predicts. An increase in the amount of money spent by households results in an increase in the flow of goods to households. This, in turn, generates an increase in demand for factors of production by firms. So, there is an increase in the number of jobs in the economy.

Solutions appear at back of book.