So Why Are There Price Ceilings?

We have seen three common results of price ceilings:

A persistent shortage of the good

Inefficiency arising from this persistent shortage in the form of inefficiently low quantity transacted, inefficient allocation of the good to consumers, resources wasted in searching for the good, and the inefficiently low quality of the good offered for sale

The emergence of illegal, black market activity

Given these unpleasant consequences of price ceilings, why do governments still sometimes impose them? Why does rent control, in particular, persist in New York?

One answer is that although price ceilings may have adverse effects, they do benefit some people. In practice, New York’s rent-

Also, when price ceilings have been in effect for a long time, buyers may not have a realistic idea of what would happen without them. In our previous example, the rental rate in an unregulated market (Figure 4-1) would be only 25% higher than in the regulated market (Figure 4-2): $1,000 instead of $800. But how would renters know that? Indeed, they might have heard about black market transactions at much higher prices—

A last answer is that government officials often do not understand supply and demand analysis! It is a great mistake to suppose that economic policies in the real world are always sensible or well informed.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Price Controls in Venezuela: “You Buy What They Have”

Price Controls in Venezuela: “You Buy What They Have”

By all accounts, Venezuela is a rich country—

The origins of Venezuela’s food shortages can be traced to the policies put in place by former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez and continued by his successor, Nicolás Maduro. Chávez came to power in 1998 on a platform denouncing the country’s economic elite and promising policies that favored the poor and working class, including price controls on basic foodstuffs. These price controls led to shortages that began in 2003 and became severe by 2006. Prices were set so low that farmers reduced production. For example, Venezuela was a coffee exporter until 2009 when it was forced to import large amounts of coffee to make up for a steep fall in production. Venezuela now imports more than 70% of its food.

In addition, generous government programs for the poor and working class led to higher demand. The combination of price controls and higher demand led to sharply rising prices for goods that weren’t subject to price controls or that were bought on the black market. The result was a big increase in the demand for price-

Worse yet, a sharp decline in the value of the Venezuelan currency made foreign imports more expensive. And it increased the incentives for smuggling: when goods are available at the government-

Venezuelans, queuing for hours to purchase goods at state-

Quick Review

Price controls take the form of either legal maximum prices—

price ceilings—or legal minimum prices— price floors. A price ceiling below the equilibrium price benefits successful buyers but causes predictable adverse effects such as persistent shortages, which lead to four types of inefficiencies: inefficiently low quantity transacted, inefficient allocation to consumers, wasted resources, and inefficiently low quality.

Price ceilings also lead to black markets, as buyers and sellers attempt to evade the price controls.

4-1

Question 4.1

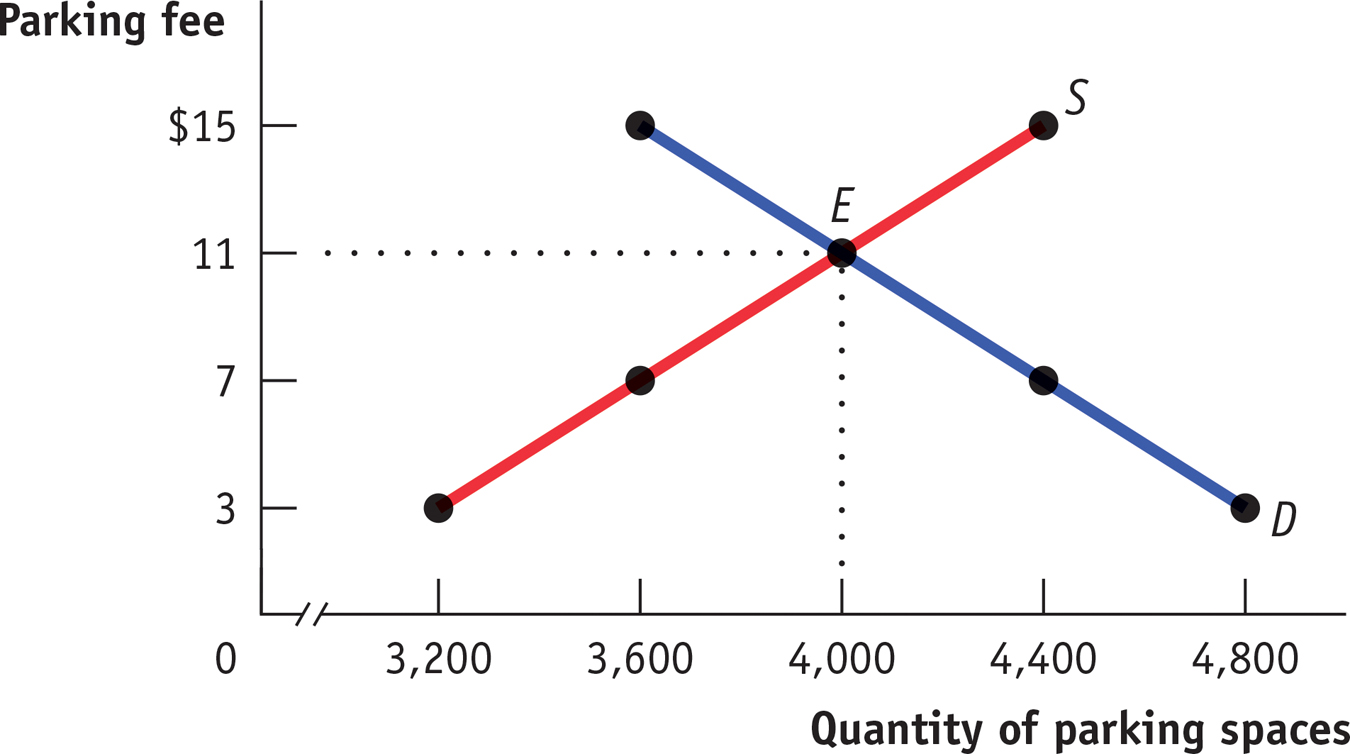

On game days, homeowners near Middletown University’s stadium used to rent parking spaces in their driveways to fans at a going rate of $11. A new town ordinance now sets a maximum parking fee of $7. Use the accompanying supply and demand diagram to explain how each of the following corresponds to a price-

ceiling concept.

Some homeowners now think it’s not worth the hassle to rent out spaces.

Some fans who used to carpool to the game now drive alone.

Some fans can’t find parking and leave without seeing the game.

Explain how each of the following adverse effects arises from the price ceiling.

Some fans now arrive several hours early to find parking.

Friends of homeowners near the stadium regularly attend games, even if they aren’t big fans. But some serious fans have given up because of the parking situation.

Some homeowners rent spaces for more than $7 but pretend that the buyers are nonpaying friends or family.

Question 4.2

True or false? Explain your answer. A price ceiling below the equilibrium price of an otherwise efficient market does the following:

Increases quantity supplied

Makes some people who want to consume the good worse off

Makes all producers worse off

Solutions appear at back of book.