The Effects of a Tariff

A tariff is a tax levied on imports.

A tariff is a form of excise tax, one that is levied only on sales of imported goods. For example, the U.S. government could declare that anyone bringing in phones must pay a tariff of $100 per unit. In the distant past, tariffs were an important source of government revenue because they were relatively easy to collect. But in the modern world, tariffs are usually intended to discourage imports and protect import-

The tariff raises both the price received by domestic producers and the price paid by domestic consumers. Suppose, for example, that our country imports phones, and a phone costs $200 on the world market. As we saw earlier, under free trade the domestic price would also be $200. But if a tariff of $100 per unit is imposed, the domestic price will rise to $300, because it won’t be profitable to import phones unless the price in the domestic market is high enough to compensate importers for the cost of paying the tariff.

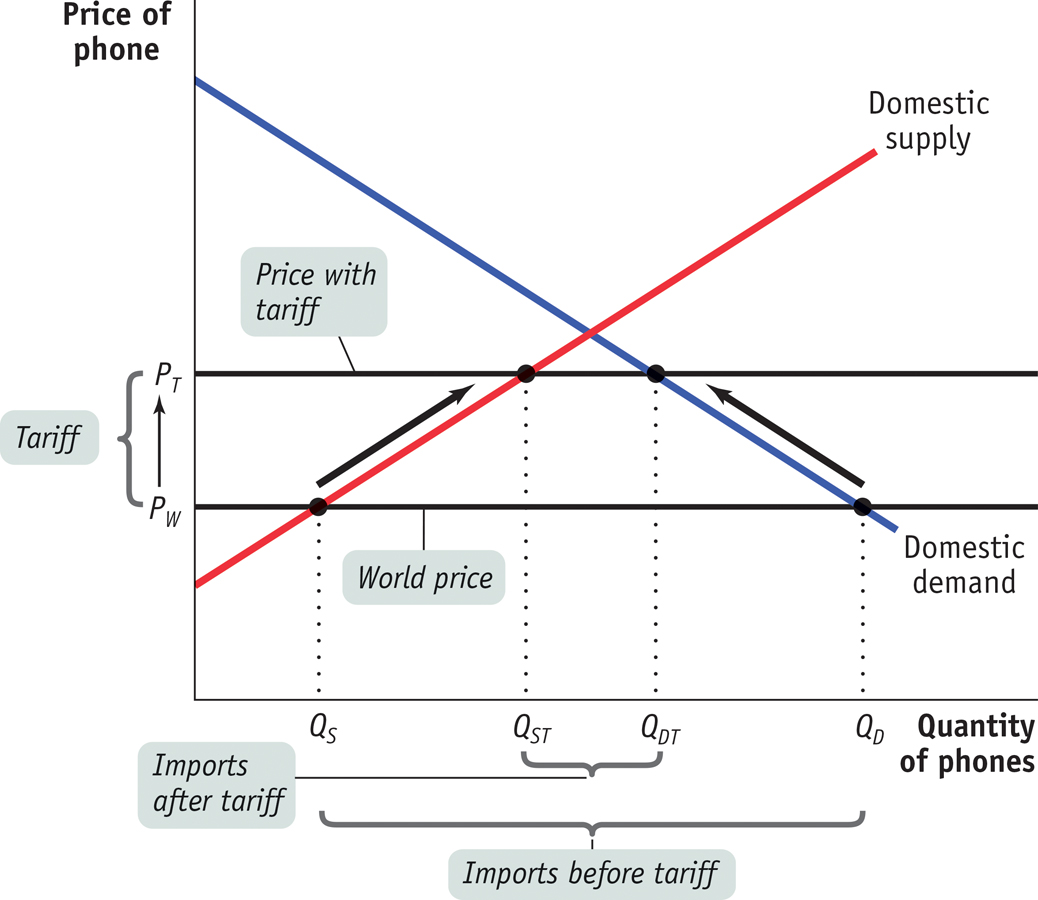

Figure 5-10 illustrates the effects of a tariff on imports of phones. As before, we assume that PW is the world price of a phone. Before the tariff is imposed, imports have driven the domestic price down to PW, so that pre-

Now suppose that the government imposes a tariff on each phone imported. As a consequence, it is no longer profitable to import phones unless the domestic price received by the importer is greater than or equal to the world price plus the tariff. So the domestic price rises to PT, which is equal to the world price, PW, plus the tariff. Domestic production rises to QST, domestic consumption falls to QDT, and imports fall to QDT − QST.

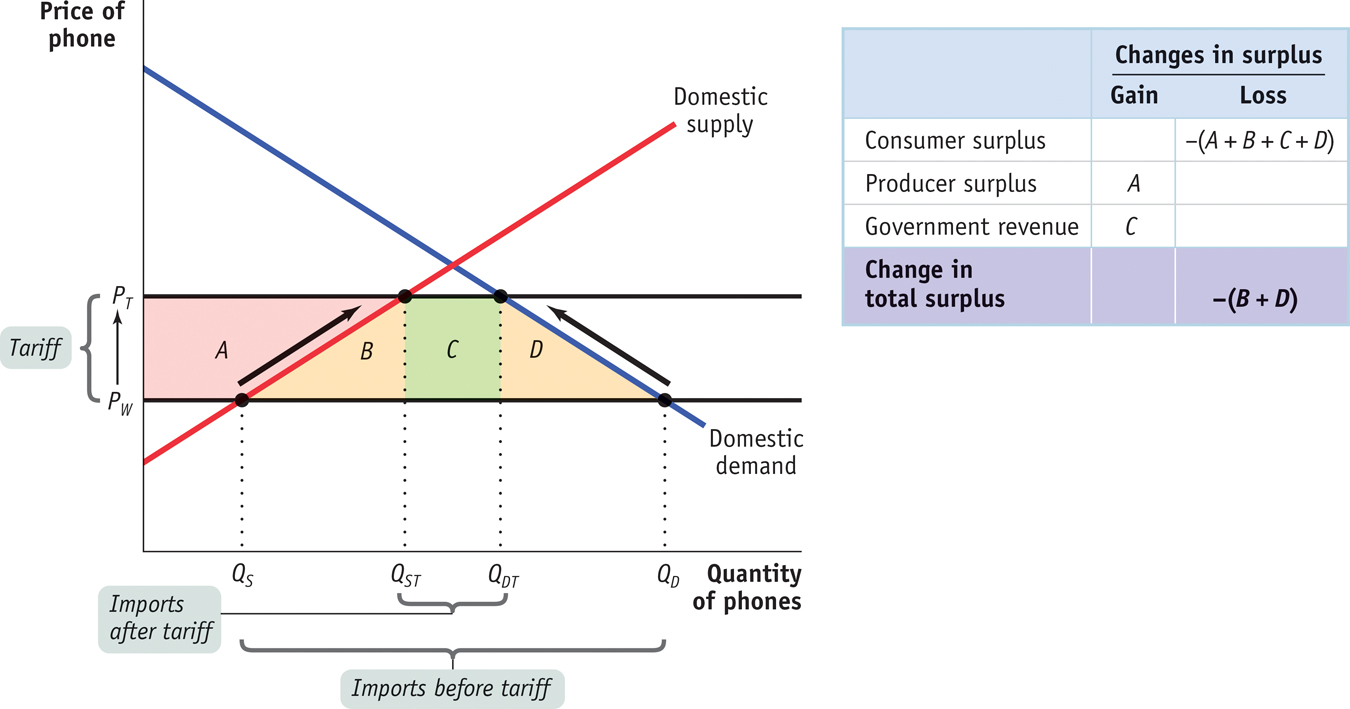

A tariff, then, raises domestic prices, leading to increased domestic production and reduced domestic consumption compared to the situation under free trade. Figure 5-11 shows the effects on surplus. There are three effects:

The higher domestic price increases producer surplus, a gain equal to area A.

The higher domestic price reduces consumer surplus, a reduction equal to the sum of areas A, B, C, and D.

The tariff yields revenue to the government. How much revenue? The government collects the tariff—

which, remember, is equal to the difference between PT and PW on each of the QDT − QST units imported. So total revenue is (PT − PW) × (QDT − QST). This is equal to area C.

The welfare effects of a tariff are summarized in the table in Figure 5-11. Producers gain, consumers lose, and the government gains. But consumer losses are greater than the sum of producer and government gains, leading to a net reduction in total surplus equal to areas B + D.

An excise tax creates inefficiency, or deadweight loss, because it prevents mutually beneficial trades from occurring. The same is true of a tariff, where the deadweight loss imposed on society is equal to the loss in total surplus represented by areas B + D.

Tariffs generate deadweight losses because they create inefficiencies in two ways:

Some mutually beneficial trades go unexploited: some consumers who are willing to pay more than the world price, PW, do not purchase the good, even though PW is the true cost of a unit of the good to the economy. The cost of this inefficiency is represented in Figure 5-11 by area D.

The economy’s resources are wasted on inefficient production: some producers whose cost exceeds PW produce the good, even though an additional unit of the good can be purchased abroad for PW. The cost of this inefficiency is represented in Figure 5-11 by area B.