The Effects of an Import Quota

An import quota is a legal limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported.

An import quota, another form of trade protection, is a legal limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported. For example, a U.S. import quota on Chinese phones might limit the quantity imported each year to 50 million units. Import quotas are usually administered through licenses: a number of licenses are issued, each giving the license-

A quota on sales has the same effect as an excise tax, with one difference: the money that would otherwise have accrued to the government as tax revenue under an excise tax becomes license-

Who receives import licenses and so collects the quota rents? In the case of U.S. import protection, the answer may surprise you: the most important import licenses—

Because the quota rents for most U.S. import quotas go to foreigners, the cost to the nation of such quotas is larger than that of a comparable tariff (a tariff that leads to the same level of imports). In Figure 5-11 the net loss to the United States from such an import quota would be equal to areas B + C + D, the difference between consumer losses and producer gains.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Trade Protection in The United States

Trade Protection in The United States

The United States today generally follows a policy of free trade, both in comparison with other countries and in comparison with its own history. Most imports are subject to either no tariff or to a low tariff. So what are the major exceptions to this rule?

Most of the remaining protection involves agricultural products. Topping the list is ethanol, which in the United States is mainly produced from corn and used as an ingredient in motor fuel. Most imported ethanol is subject to a fairly high tariff, but some countries are allowed to sell a limited amount of ethanol in the United States, at high prices, without paying the tariff. Dairy products also receive substantial import protection, again through a combination of tariffs and quotas.

Until a few years ago, clothing and textiles were also strongly protected from import competition, thanks to an elaborate system of import quotas. However, this system was phased out in 2005 as part of a trade agreement reached a decade earlier. Some clothing imports are still subject to relatively high tariffs, but protection in the clothing industry is a shadow of what it used to be.

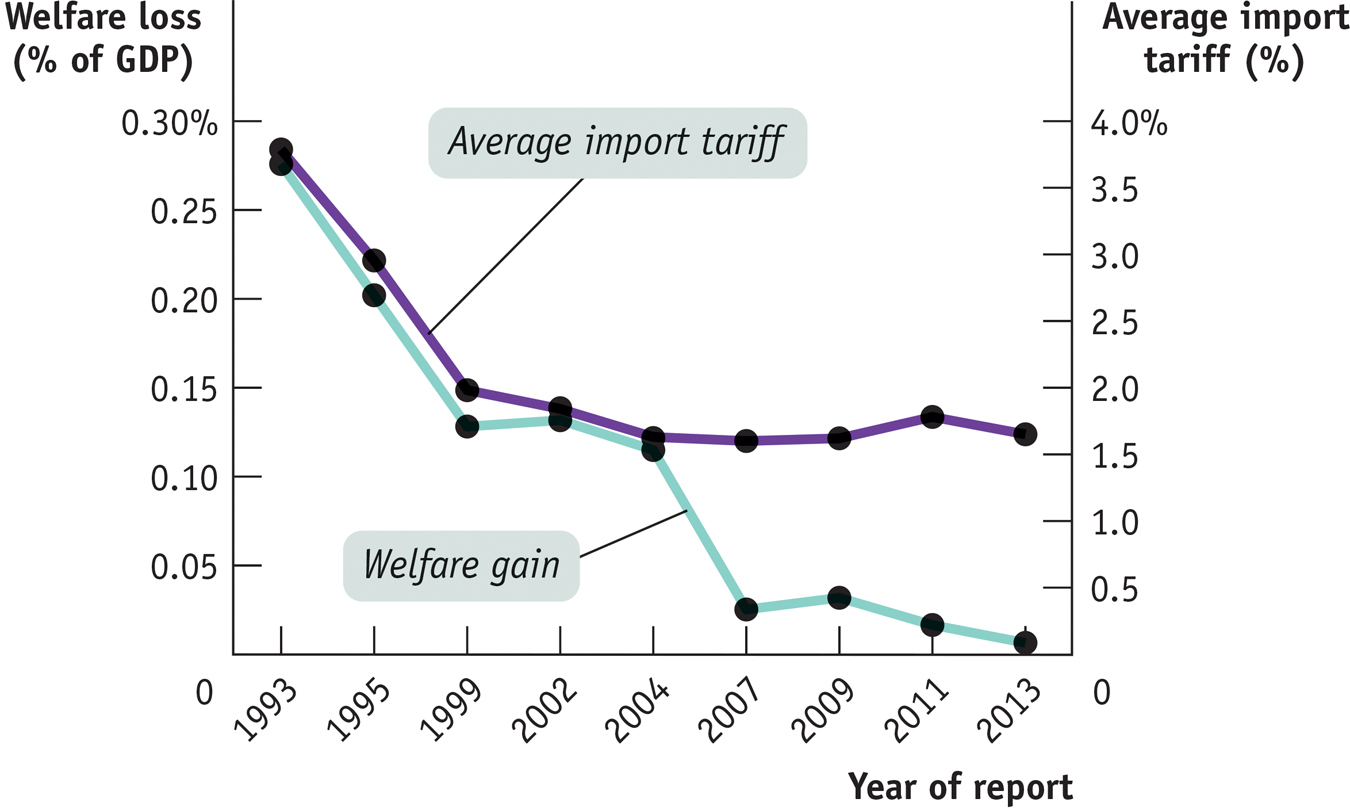

The most important thing to know about current U.S. trade protection is how limited it really is, and how little cost it imposes on the economy. Every two years the U.S. International Trade Commission, a government agency, produces estimates of the impact of “significant trade restrictions” on U.S. welfare. As Figure 5-12 shows, over the past two decades both average tariff levels and the cost of trade restrictions as a share of national income, which weren’t all that big to begin with, have fallen sharply.

Quick Review

Most economists advocate free trade, although many governments engage in trade protection of import-

competing industries. The two most common protectionist policies are tariffs and import quotas. In rare instances, governments subsidize exporting industries. A tariff is a tax on imports. It raises the domestic price above the world price, leading to a fall in trade and domestic consumption and a rise in domestic production. Domestic producers and the government gain, but domestic consumer losses more than offset this gain, leading to deadweight loss.

An import quota is a legal quantity limit on imports. Its effect is like that of a tariff, except that revenues—

the quota rents— accrue to the license holder, not to the domestic government.

5-3

Question 5.5

Suppose the world price of butter is $0.50 per pound and the domestic price in autarky is $1.00 per pound. Use a diagram similar to Figure 5-10 to show the following.

If there is free trade, domestic butter producers want the government to impose a tariff of no less than $0.50 per pound. Compare the outcome with a tariff of $0.25 per pound.

What happens if a tariff greater than $0.50 per pound is imposed?

Question 5.6

Suppose the government imposes an import quota rather than a tariff on butter. What quota limit would generate the same quantity of imports as a tariff of $0.50 per pound?

Solutions appear at back of book.